Engram: How DeepSeek Added a Second Brain to Their LLM

When DeepSeek released their technical reports for V2 and V3, the ML community focused on the obvious innovations: massive parameter counts, clever load balancing, and Multi-head Latent Attention. But buried in their latest research is something that deserves more attention: a different way to think about what an LLM should remember.

The insight is deceptively simple. Large language models spend enormous computational effort reconstructing patterns they've seen millions of times before. The phrase "United States of" almost certainly ends with "America." "New York" probably precedes "City" or "Times." These patterns are burned into the training data, and the model learns them, but it learns them the hard way: by propagating gradients through billions of parameters across dozens of layers.

What if you could just look them up?

Think of it like the difference between calculating 7 x 8 every time someone asks versus memorizing the multiplication table. Both give you 56, but one is faster. Engram takes this principle and applies it to language model architecture.

That's the core idea behind Engram, DeepSeek's conditional memory architecture. Rather than forcing the model to reconstruct common N-gram patterns through neural computation, Engram stores them in a lookup table and retrieves them with O(1) complexity. The result is a model that "achieves superior performance over a strictly iso-parameter and iso-FLOPs MoE baseline" [1], with striking gains in knowledge benchmarks (MMLU +3.0, CMMLU +4.0) and reasoning tasks (BBH +5.0) [1].

But the implications run deeper than benchmark numbers. Engram represents a new axis of sparsity for LLMs, one that complements rather than competes with Mixture-of-Experts approaches. Let me show you how it works.

Why N-grams? A Return to Statistical Language Modeling

Before diving into architecture, some historical context helps explain why Engram's approach is clever rather than obvious.

N-gram models dominated NLP before deep learning. They worked by counting how often sequences of words appeared together in training data. The problem was sparsity: most N-grams never appear in any training corpus, so the model has no information about them.

Neural language models solved this by learning distributed representations that generalize. But they threw away something valuable: the direct lookup of known patterns. If your model has seen "the quick brown fox" millions of times, why should it waste compute rediscovering this pattern?

Engram reclaims this efficiency. Its embedding table stores knowledge about common N-gram patterns, and "natural language N-grams follow a Zipfian distribution where a small fraction of patterns accounts for the vast majority of memory accesses" [1]. Most tokens fall into well-trodden paths that can be retrieved rather than computed.

The practical implication: "Engram relieves the backbone's early layers from static reconstruction, effectively deepening the network for complex reasoning" [1]. By delegating pattern recognition to lookups, the transformer's attention capacity is freed for global context understanding.

The Two Types of Memory an LLM Needs

Modern LLMs face a core tension. They need to store two different types of knowledge: factual associations (what's the capital of France?) and reasoning patterns (how do you solve a logic puzzle?). These place different demands on the architecture.

Factual associations are lookup operations. Given the right cue, the answer should pop out immediately. You don't reason your way to "Paris" when asked about France's capital; you retrieve it. This is what Engram calls "conditional memory," which "relies on sparse lookup operations to retrieve static embeddings for fixed knowledge" [1].

Reasoning, by contrast, requires computation. You can't look up the answer to a novel math problem; you have to work through it step by step. This is where the traditional neural network excels, using its deep stack of attention and feed-forward layers to transform inputs into outputs.

The problem is that standard Transformers use the same mechanism for both. Every piece of knowledge, whether it's a simple factual association or a complex reasoning pattern, gets processed through the same expensive attention and FFN computations. This is wasteful.

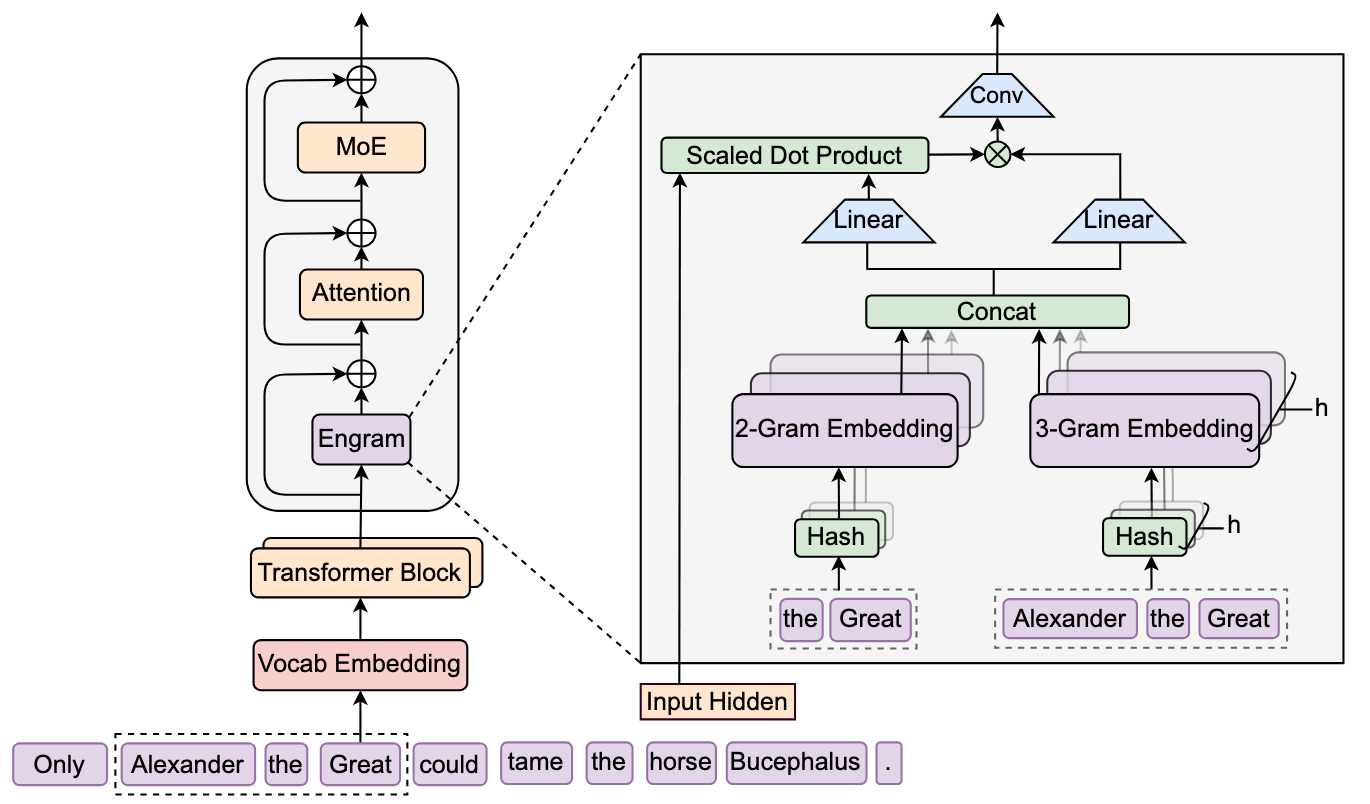

Figure 1: The Engram Architecture showing N-gram retrieval and context-aware fusion with transformer backbone. Source: DeepSeek Engram

Figure 1: The Engram Architecture showing N-gram retrieval and context-aware fusion with transformer backbone. Source: DeepSeek Engram

How Engram Actually Works

The architecture has four key components, and they work together in a clever way. Let me walk through each one.

1. Tokenizer Compression: Reducing the Lookup Space

The first challenge is practical: if you want to store embeddings for every possible N-gram, the table gets enormous fast. A vocabulary of 128K tokens would generate 128K x 128K = 16 billion possible 2-grams alone.

Engram solves this with tokenizer compression, which "achieves a 23% reduction in the effective vocabulary size for a 128k tokenizer" [1]. The key insight is that many tokens are semantically redundant. "Hello" and "hello" and "HELLO" might all collapse to the same representation for the purposes of N-gram lookup.

This compression happens at training time and is fixed during inference, keeping the lookup table manageable while preserving the patterns that matter.

2. Multi-Head Hashing: Handling Collisions

Even with compression, you'll have hash collisions. Different N-grams will map to the same memory location. Engram addresses this by employing "K distinct hash heads for each N-gram order n to mitigate collisions" [1].

Think of it like having multiple parallel hash tables, each using a different hash function. If one head produces a collision, the others likely won't. When you retrieve embeddings, you aggregate across all heads, reducing the impact of any single collision.

This mirrors the multi-head attention intuition: different heads capture different aspects of the representation, and their combination is more robust than any single head.

class MultiHeadHashEmbedding:

"""

Multi-head hashing for N-gram embeddings.

Uses K independent hash functions to map each N-gram to K different

embedding vectors, then concatenates them. This reduces the impact

of hash collisions since it's unlikely that two N-grams will collide

across all K hash functions simultaneously.

"""

def __init__(self, config: EngramConfig, seed: int = 42):

self.config = config

# Initialize hash function parameters (multiplicative-XOR hash)

# Each (n-gram order, hash head) pair has its own hash parameters

self._init_hash_params()

self._init_embedding_tables()

def compute_ngram_hash(self, ngram_tokens: Tuple[int, ...], n: int, k: int) -> int:

"""Compute hash index using multiplicative-XOR hash: h(x) = ((a * x) XOR b) mod M"""

a, b = self.hash_params[(n, k)]

# Combine token IDs using polynomial rolling hash

combined = 0

for token_id in ngram_tokens:

combined = (combined * 31 + token_id) & 0x7FFFFFFF

return ((a * combined) ^ b) % self.config.table_size

def lookup_embedding(self, token_ids: List[int], position: int) -> np.ndarray:

"""Retrieve aggregated N-gram embedding for a position."""

all_embeddings = []

for n, ngram in self.extract_ngrams(token_ids, position):

# Multi-head hashing: K independent hash functions per N-gram order

for k in range(self.config.num_hash_heads):

hash_idx = self.compute_ngram_hash(ngram, n, k)

embedding = self.embedding_tables[(n, k)][hash_idx]

all_embeddings.append(embedding)

# Concatenate embeddings from all heads and N-gram orders

return np.concatenate(all_embeddings, axis=-1)

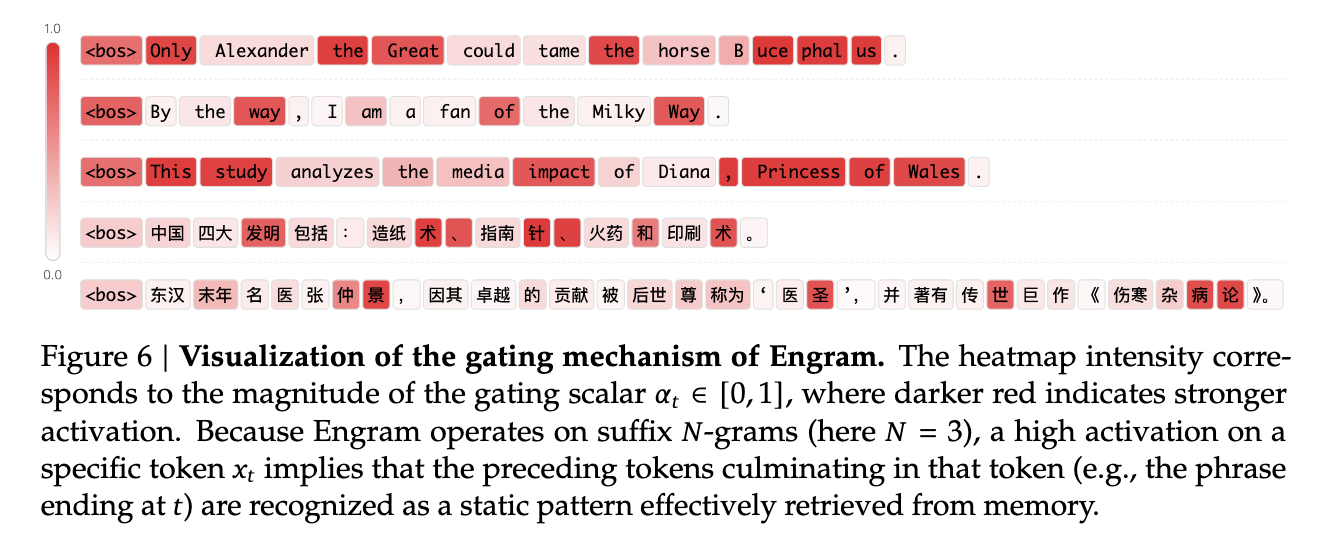

3. Context-Aware Gating: Knowing When to Use Memory

Here's where things get interesting. Not every position in a sequence benefits equally from N-gram memory. Sometimes the local context is highly predictable ("United States of _"), and the lookup is valuable. Other times, the next token depends on long-range dependencies that N-grams can't capture.

Consider a concrete example. When the model sees "New York City" at the end of a sentence, the N-gram lookup is highly valuable. But when it sees "The city that" in the middle of a complex sentence, the next word depends on context that spans paragraphs, not local patterns.

Engram uses a "context-aware gating mechanism inspired by Attention using hidden state as dynamic Query" [1]. The model's current hidden state acts as a query that determines how much weight to give the retrieved memory versus the standard neural computation.

This is crucial. Without gating, you'd either always use the memory (bad for novel contexts) or never use it (defeating the purpose). The gating mechanism lets the model learn when N-gram patterns are trustworthy.

Case study showing how Engram modulates memory retrieval based on input context. Source: DeepSeek Engram

Case study showing how Engram modulates memory retrieval based on input context. Source: DeepSeek Engram

4. Multi-Branch Integration: Processing Different N-gram Orders

Natural language has patterns at multiple scales. Bigrams like "New York" are common, but so are trigrams like "in order to" and even longer phrases. Engram handles this by maintaining separate branches for different N-gram orders, then combining them through learned convolutions.

The technical detail: Engram "uses kernel size w=4 and dilation delta set to max N-gram order for causal convolution" [1]. The causal constraint ensures the model can't cheat by looking at future tokens, and "convolution parameters initialized to zero to preserve identity mapping at start of training" [1] means the model starts from a sensible baseline.

The model instantiates "the module at layers 2 and 15 with maximum N-gram size of 3" [1]. This placement is intentional. Early layers (layer 2) benefit from N-gram information for building initial representations. Mid-layers (layer 15) use it to augment reasoning with contextual patterns.

The System Picture: Training and Inference

So far I've described the architecture in abstract terms. But Engram has to actually run on hardware, and that introduces new challenges.

Training: GPU-Sharded Embedding Tables

During training, the embedding table is sharded across GPUs using All2All communication. This is necessary because the table can grow large, but it introduces synchronization overhead. The embedding parameters are "updated using Adam with learning rate scaled by 5x and no weight decay" [1], treating them differently from neural weights.

Inference: CPU Offloading with Prefetching

Here's where Engram's design shines. Because the N-gram IDs are deterministic (they depend only on the input tokens, not on any neural computation), you can prefetch them. The paper notes that "deterministic IDs enable runtime prefetching, overlapping communication with computation" [1]. While the GPU is computing attention for the current layer, the system is already loading the Engram embeddings for the next lookup.

Even more striking: "offloading a 100B-parameter table to host memory incurs negligible overhead (< 3%)" [1]. You can store an enormous lookup table in CPU RAM and still maintain near-GPU-speed inference. This is possible because the lookup is sparse and can be overlapped with computation.

This property is key. Attention-based memory systems can't prefetch because the attention weights depend on the current hidden state. Engram's direct addressing enables pipelining that attention cannot match.

Multi-Level Cache Hierarchy

The Zipfian distribution of N-gram accesses enables another optimization: "Multi-Level Cache Hierarchy enables caching frequent embeddings in faster storage tiers (GPU HBM or Host DRAM)" [1].

The most common patterns live in fast GPU memory. Less common patterns get fetched from CPU DRAM. The long tail lives in slower storage. Because access patterns are predictable and heavily skewed, the cache hit rate is high.

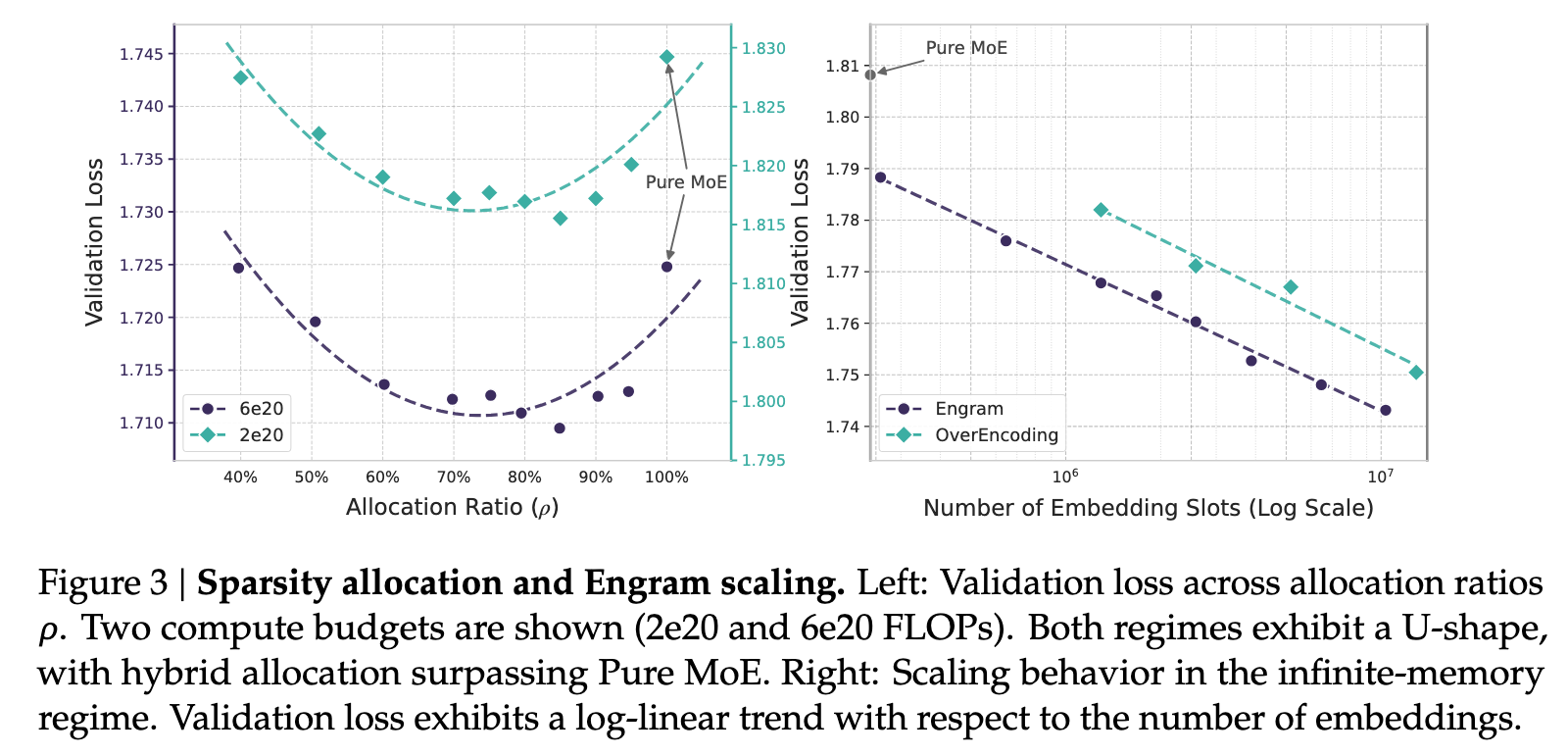

The U-Shaped Scaling Law

Here's where Engram gets theoretically interesting. The authors discovered a "U-shaped scaling law that optimizes the trade-off between neural computation (MoE) and static memory (Engram)" [1].

What does this mean? Given a fixed parameter budget, you have to decide how to allocate between MoE experts (which do dynamic computation) and Engram tables (which store static patterns). Allocate too much to MoE, and you waste capacity on reconstructing patterns that could be looked up. Allocate too much to Engram, and you lack the computational depth for complex reasoning.

Optimal sparsity allocation between Engram memory and MoE experts showing the U-shaped loss curve. Source: DeepSeek Engram

Optimal sparsity allocation between Engram memory and MoE experts showing the U-shaped loss curve. Source: DeepSeek Engram

The empirical finding is that the "pure MoE baseline proves suboptimal: reallocating roughly 20%-25% of sparse parameter budget to Engram yields best performance" [1]. In the 10B regime, "validation loss improves from 1.7248 (at rho = 100%) to 1.7109 near the optimum of rho = 80%" [1].

Even more surprisingly, this allocation is robust. The "location of optimum is stable across regimes (rho = 75%-80%)" [1], meaning the same approximate split works whether you're training a 5B or 27B model.

What does this mean practically? If you're training a sparse model, allocating a portion of your parameter budget to fast-lookup memory tables beats using all of it for MoE experts.

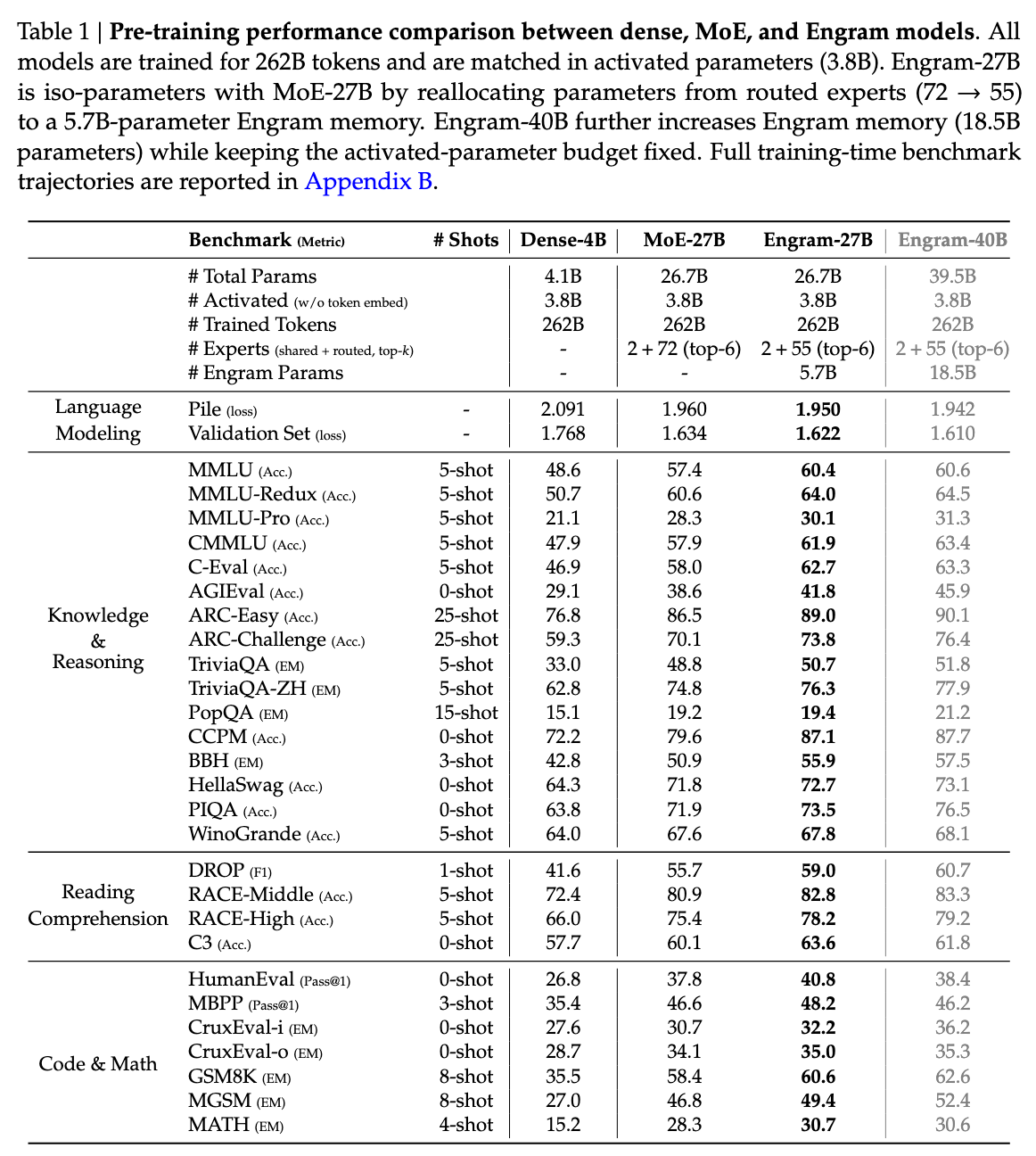

Benchmark Results: Where Engram Shines

The Engram-27B model was trained with an identical data curriculum to a pure MoE baseline with the same parameter count. "All models trained for 262B tokens with identical data curriculum" [1] using a "30-block Transformer with hidden size of 2560 and MLA with 32 heads" [1]. The comparison is as close to apples-to-apples as you'll get in LLM research.

Here's what happened:

Knowledge Benchmarks

| Benchmark | Engram-27B | MoE-27B | Delta |

|---|---|---|---|

| MMLU | 60.4 | 57.4 | +3.0 |

| CMMLU | 61.9 | 57.9 | +4.0 |

Reasoning Benchmarks

| Benchmark | Engram-27B | MoE-27B | Delta |

|---|---|---|---|

| BBH | 55.9 | 50.9 | +5.0 |

| DROP | 59.0 | 55.7 | +3.3 |

Code and Math

| Benchmark | Engram-27B | MoE-27B | Delta |

|---|---|---|---|

| HumanEval | 40.8 | 37.8 | +3.0 |

| MATH | 30.7 | 28.3 | +2.4 |

| GSM8K | 60.6 | 58.4 | +2.2 |

Sources: [1]

The pattern is consistent: Engram helps across the board, but the gains are largest in knowledge-intensive tasks. This makes intuitive sense. MMLU and CMMLU test factual recall, exactly the kind of lookup operation that Engram accelerates.

The reasoning gains are more interesting. Why would memory lookup help with reasoning tasks? The answer lies in what Engram frees up. When early layers don't need to handle pattern matching, they can instead propagate more abstract representations. The model effectively has more depth available for reasoning.

Comprehensive benchmark performance showing Engram's consistent improvements across knowledge, reasoning, and code/math domains. Source: DeepSeek Engram

Comprehensive benchmark performance showing Engram's consistent improvements across knowledge, reasoning, and code/math domains. Source: DeepSeek Engram

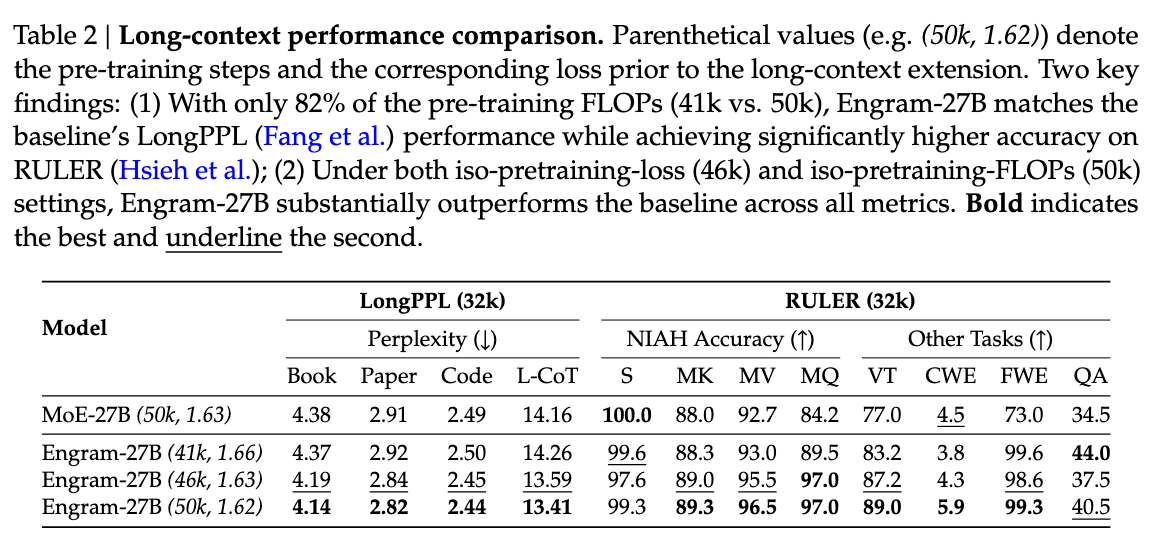

Long-Context Performance: The Real Surprise

The benchmark where Engram really stands out is long-context retrieval. "Multi-Query NIAH: 84.2 to 97.0 improvement in long-context retrieval" [1]. That's a 12.8-point improvement, much larger than any single-task gain. Variable Tracking shows similar results: "89.0 vs. 77.0 improvement with Engram" [1].

Why? The paper argues that "Engram relieves the backbone's early layers from static reconstruction, effectively deepening the network for complex reasoning" [1]. By offloading simple pattern matching to the lookup table, the attention layers can focus on what they're good at: modeling long-range dependencies.

This connects to another insight: "by delegating local dependencies to lookups, Engram frees up attention capacity for global context" [1]. Attention has a fixed budget of capacity per layer. If it's not spending that budget on reconstructing "New York City," it can use it for tracking coreference across thousands of tokens.

Long-context performance showing Engram's significant improvements in retrieval tasks. Source: DeepSeek Engram

Long-context performance showing Engram's significant improvements in retrieval tasks. Source: DeepSeek Engram

Mechanistic Analysis: What's Actually Happening Inside

The benchmarks show Engram helps, but why? The paper includes CKA (Centered Kernel Alignment) analysis showing how representations evolve through the network.

The key finding: early layers in Engram models develop representations more similar to later layers in baseline models. Engram layers show different representation patterns than pure MoE layers, suggesting they're learning complementary functions. Engram handles pattern-matching; MoE handles composition and reasoning.

This confirms the theoretical intuition. You don't want two systems doing the same thing. Engram succeeds because it's genuinely different from neural computation, not just a cheaper approximation.

What This Means for Architecture Design

Let me step back and consider what Engram tells us about LLM architecture more broadly.

The standard approach to scaling has been: more parameters, more layers, more data. Engram suggests a different dimension: better memory organization. Some knowledge is static and should be retrieved; other knowledge is dynamic and requires computation. Mixing them in the same mechanism is inefficient.

This parallels human cognition in an interesting way. We don't reason our way to our home address every time someone asks; we retrieve it from memory. But we do reason through novel problems. The brain appears to have different systems for different types of knowledge, and maybe LLMs should too.

The DeepSeek Ecosystem Context

Engram builds on innovations from DeepSeek's earlier work. Their V3 model is "a strong MoE language model with 671B total parameters with 37B activated for each token" [2], trained using an "auxiliary-loss-free strategy for load balancing" [2] that "minimizes adverse impact on model performance."

The MLA (Multi-head Latent Attention) mechanism they pioneered achieves "approximately 65% reduction in KV cache size compared to standard attention" [3]. Combined with Engram's memory offloading, this creates a system where both attention (KV cache) and pattern memory (Engram tables) can be stored efficiently.

The expert configuration tells the story: "Engram-27B uses 2+55 experts (top-6) vs MoE-27B's 2+72 experts" [1]. By replacing 17 experts with Engram memory, they got better performance with fewer computational experts. The N-gram patterns that would have consumed expert capacity are now handled by simple lookups.

Load Balancing Without Auxiliary Loss

One reason Engram integrates cleanly with DeepSeek's architecture is their auxiliary-loss-free load balancing. Traditional MoE training adds a loss term encouraging balanced expert usage, which creates optimization conflicts.

DeepSeek's approach introduces a "bias term for each expert to determine top-K routing without affecting gating values" [2]. The bias adjusts based on recent expert load, providing self-tuning load balancing without distorting the learning signal.

This is relevant to Engram because the memory module needs to integrate cleanly with the MoE routing. The auxiliary-loss-free approach means Engram doesn't need to fight with auxiliary gradients.

Practical Implications for ML Engineers

If you're building LLM applications, what should you take away from this?

When Engram Helps Most

Based on the benchmark results, Engram provides the largest gains for:

- Factual recall tasks: Anything involving lookup of known facts

- Long-context retrieval: Tasks requiring information retrieval across long documents

- Pattern-heavy domains: Applications where common phrases and idioms dominate

The gains are smaller but still positive for:

- Novel reasoning: Multi-step logic that requires composition

- Code generation: Where syntax patterns help but novel logic dominates

- Mathematical reasoning: Moderately pattern-dependent

Memory-Compute Tradeoffs

Engram shifts the memory-compute balance. You're trading embedding table storage for reduced neural computation. The < 3% overhead from 100B parameter offloading suggests this is favorable for most deployments.

But there are cases where it might not be:

- Memory-constrained edge deployment: If you can't afford the embedding table at all

- Latency-critical real-time: If any CPU-GPU communication adds unacceptable latency

- Highly dynamic domains: If your patterns change faster than you can retrain embeddings

Key Design Principles

-

Memory matters more than you think. The standard Transformer architecture has no explicit memory beyond the KV cache and learned weights. Engram shows that adding a dedicated retrieval mechanism can improve performance across the board.

-

Sparsity has multiple axes. MoE is one form of sparsity (activating a subset of experts). Engram is another (looking up patterns rather than computing them). These can be combined, and the combination may be better than either alone.

-

Offloading is underrated. The < 3% overhead for 100B parameters in host memory is remarkable. If you're memory-constrained at inference time, consider what can be moved to CPU without killing latency.

-

Deterministic addressing enables optimization. If you can predict memory access patterns from inputs, you can prefetch and hide latency. Design with this in mind.

class TransformerBlockWithEngram(nn.Module):

"""Transformer block with integrated Engram conditional memory.

Architecture:

h = h + Attention(LayerNorm(h))

h = h + Engram(h, input_ids) # <-- Engram insertion point

h = h + MLP(LayerNorm(h))

"""

def forward(self, hidden_states, input_ids, attention_mask=None):

# Self-Attention with residual connection

normed = self.attn_norm(hidden_states)

attn_output, _ = self.attention(normed, normed, normed, attn_mask=causal_mask)

hidden_states = hidden_states + attn_output

# Engram: Conditional Memory Lookup and Fusion

if self.use_engram:

# Step 1: Retrieve N-gram embeddings via O(1) hashing

memory = self.hash_embedding(input_ids)

# Step 2: Context-aware gating

# Query = hidden state, Key/Value = memory

key = self.W_K(memory)

value = self.W_V(memory)

gate = torch.sigmoid(torch.sum(self.query_norm(hidden_states) * self.key_norm(key), dim=-1, keepdim=True) / self.scale)

engram_output = gate * value

# Add to residual stream (not concatenate!)

hidden_states = hidden_states + engram_output

# MLP with residual connection

hidden_states = hidden_states + self.mlp(self.mlp_norm(hidden_states))

return hidden_states

What's Missing

A few things the paper doesn't address that I'd like to see:

Fine-tuning behavior. The Engram embeddings are trained from scratch. What happens if you fine-tune on a new domain? Do the N-gram patterns transfer, or do you need to retrain the lookup table?

Dynamic updates. The paper describes Engram as "static embeddings for fixed knowledge." But what if you want to update the model's knowledge without full retraining? Can you modify the Engram table independently?

Cross-lingual effects. The CMMLU results (Chinese) are strong, but were the N-gram tables trained separately for Chinese, or do they share structure with English? Multilingual models would need to handle this carefully.

Interaction with other memory mechanisms. How does Engram interact with retrieval augmentation (RAG)? They're both forms of memory, but at different levels of abstraction.

The Bigger Picture

Engram is part of a broader trend toward hybrid architectures that combine different computational mechanisms. We've seen this with MoE (dense attention + sparse experts), with retrieval augmentation (parametric model + external retrieval), and now with N-gram memory (neural computation + lookup tables).

The pattern that keeps emerging: there's no single mechanism that's optimal for everything. Attention is great for long-range dependencies but expensive for local patterns. Feed-forward networks are great for transformations but wasteful for lookup. Expert routing is great for specialization but adds coordination overhead.

The best architectures seem to be ones that assign different mechanisms to different subtasks. Engram is a particularly clean example: N-grams are handled by lookup, everything else by neural computation, and a learned gating mechanism decides which to use.

The broader implication is that LLM architecture space remains under-explored. MoE was the first axis of sparsity. Engram adds a second. What other orthogonal dimensions might exist?

What's next? I'd bet on architectures that are even more heterogeneous, mixing different types of computation based on what the input requires. The model that can dynamically allocate between retrieval, computation, and reasoning will outperform the model that does the same thing for every token.

For now, Engram is a reminder that the Transformer architecture, for all its success, leaves performance on the table. Sometimes the best way to answer a question is just to remember the answer.

References

[1] Cheng, X., Zeng, W., Dai, D., Chen, Q., Wang, B., Xie, Z., Huang, K., Yu, X., Hao, Z., Li, Y., Zhang, H., Zhang, H., Zhao, D., & Liang, W. (2025). Conditional Memory via Scalable Lookup: A New Axis of Sparsity for Large Language Models. DeepSeek-AI & Peking University.

[2] DeepSeek-AI. (2024). DeepSeek-V3 Technical Report. https://arxiv.org/abs/2412.19437

[3] DeepSeek-AI. (2024). DeepSeek-V2: A Strong, Economical, and Efficient Mixture-of-Experts Language Model. https://arxiv.org/abs/2405.04434

[4] Dai, D., et al. (2024). DeepSeekMoE: Towards Ultimate Expert Specialization in Mixture-of-Experts Language Models. https://arxiv.org/abs/2401.06066

[5] Wang, B., et al. (2024). Auxiliary-Loss-Free Load Balancing Strategy for Mixture-of-Experts. https://arxiv.org/abs/2408.15664