VL-JEPA: Why Predicting Embeddings Beats Generating Tokens for Vision-Language AI

Imagine you're describing a photo to a friend. Do you carefully select each word, wait for approval, then pick the next word? Of course not. You form a complete thought in your mind, an abstract representation of what you want to convey, and then express it. Your brain operates concept-by-concept, not word-by-word.

Yet that's precisely how most vision-language models work today. Systems like GPT-4V and LLaVA look at an image and laboriously predict one token at a time: "The," wait, "cat," wait, "is," wait, "sitting," wait... This autoregressive approach has delivered impressive results, but it carries a fundamental inefficiency baked into its design.

VL-JEPA asks a different question: what if we skipped the word-guessing entirely and predicted directly in the space where meaning lives?

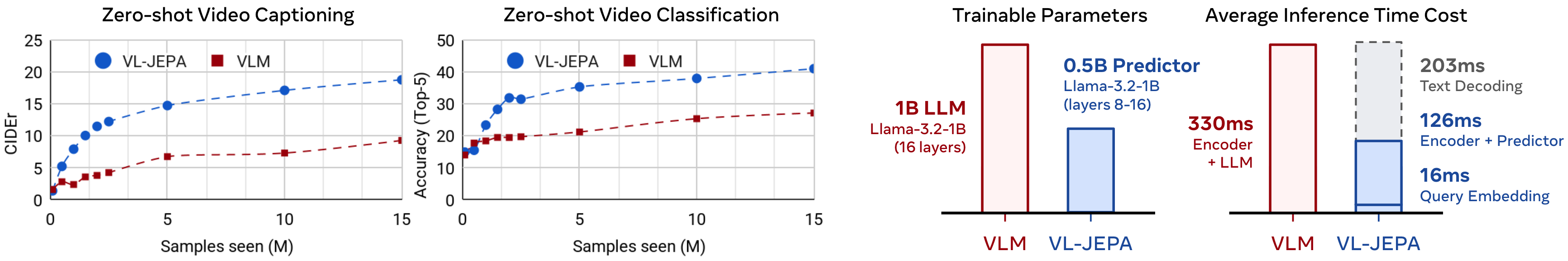

The result is a vision-language model that achieves comparable performance to classical VLMs like InstructBLIP and QwenVL with only 1.6 billion parameters, while enabling 2.85x faster decoding through adaptive selective decoding.1 This isn't just an incremental improvement. It's a different way of thinking about how vision and language should interact.

The Problem with Token-by-Token Generation

Before we can appreciate why VL-JEPA matters, we need to understand what it replaces.

Modern vision-language models like LLaVA and Flamingo follow a common pattern: connect a vision encoder to a large language model, then generate text autoregressively. The approach works remarkably well for many tasks. You can ask questions about images, generate captions, and hold conversations about visual content.

Figure 1: The Flamingo architecture connects vision and language through sequential interleaving for autoregressive text generation. Source: Flamingo Paper

Figure 1: The Flamingo architecture connects vision and language through sequential interleaving for autoregressive text generation. Source: Flamingo Paper

The problem lies in sequential decoding. As NVIDIA's technical documentation explains, "the core latency bottleneck in standard autoregressive generation is the fixed, sequential cost of each step. If a single forward pass takes 200 milliseconds, generating three tokens will always take 600 ms."2

Every token requires loading billions of parameters from memory. GPU hardware can execute hundreds of trillions of operations per second, but memory bandwidth limits how fast those operations can be fed. The result: "machine learning hardware varieties, TPUs and GPUs, are highly parallel machines, usually capable of hundreds of trillions of operations per second, while their memory bandwidth is usually around just trillions of bytes per second."3

But here's the deeper issue: "One significant shortcoming of generative methods, however, is that the model tries to fill-in every bit of missing information, even though the world is inherently unpredictable."4

When you ask a model to describe an image, the exact word choice often doesn't matter. Whether it says "cat" or "feline" or "kitty," the semantic meaning is largely equivalent. Yet token prediction forces the model to commit to exact surface forms, wasting computation on distinctions without meaningful differences.

| Approach | Mechanism | Strengths | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| CLIP/SigLIP | Contrastive alignment | Fast retrieval, zero-shot classification | No generation, limited reasoning |

| LLaVA/Flamingo | Autoregressive generation | Flexible generation, instruction following | Sequential decoding, parameter-heavy |

| VL-JEPA | Embedding prediction | Efficient, handles uncertainty | Newer approach, limited evaluation |

JEPA's Core Insight: Predict Representations, Not Pixels

To understand VL-JEPA, we first need to understand the JEPA framework that underlies it.

"Joint-Embedding Predictive Architectures learn to predict the embeddings of a signal y from a compatible signal x, using a predictor network that is conditioned on additional (possibly latent) variables z to facilitate prediction."5

Figure 2: The I-JEPA architecture predicts masked representations from context. The predictor operates entirely in embedding space, never reconstructing raw pixels. Source: I-JEPA Paper

Figure 2: The I-JEPA architecture predicts masked representations from context. The predictor operates entirely in embedding space, never reconstructing raw pixels. Source: I-JEPA Paper

The key distinction from generative approaches is what gets predicted. "Compared to generative methods that predict in pixel/token space, I-JEPA makes use of abstract prediction targets for which unnecessary pixel-level details are potentially eliminated."6

Why does this matter? "JEPA allows the system to handle uncertainty and ignore irrelevant details while maintaining essential information for making predictions."7 A generative model asked to predict what's behind an occluded object must commit to specific pixels. JEPA models instead predict abstract representations where multiple plausible futures can coexist.

The efficiency gains are substantial. I-JEPA "converges in roughly 5x fewer iterations" than comparable methods.8 Training "a ViT-Huge/14 on ImageNet using 16 A100 GPUs in under 72 hours" achieves "strong downstream performance across a wide range of tasks."9 For context: "Pretraining a ViT-H/14 on ImageNet requires less than 1200 GPU hours, which is over 2.5x faster than a ViT-S/16 pretrained with iBOT and over 10x more efficient than a ViT-H/14 pretrained with MAE."10

From Images to Video: V-JEPA

Before VL-JEPA could combine vision with language, the JEPA framework needed to handle temporal dynamics. V-JEPA extended the approach to video understanding.

"V-JEPA is a non-generative model that learns by predicting missing or masked parts of a video in an abstract representation space."11 The video domain presents additional challenges: the model must understand how scenes evolve over time, not just static spatial relationships.

Figure 3: Vision Transformers process images as sequences of patches. This foundation enables JEPA's patch-based masking strategy. Source: ViT Paper

Figure 3: Vision Transformers process images as sequences of patches. This foundation enables JEPA's patch-based masking strategy. Source: ViT Paper

The training approach uses spatiotemporal masking. "A clip of 64 frames (approximately 2.1 seconds of video at 30 frames per second) is extracted from the video and resized to 16 x 224 x 224 x 3. The clip is split into L spatiotemporal patches of size 16x16x2 (2 is the number of consecutive frames)."12

The masking strategy proves critical: "if you don't block out large regions of the video and instead randomly sample patches here and there, it makes the task too easy and your model doesn't learn anything particularly complicated about the world."13 The model must be forced to actually understand the scene rather than interpolating local patterns.

The efficiency advantage carries over to video. "Unlike generative approaches that try to fill in every missing pixel, V-JEPA has the flexibility to discard unpredictable information, which leads to improved training and sample efficiency by a factor between 1.5x and 6x."14

V-JEPA's practical value became clear in its ability to transfer to downstream tasks. "V-JEPA is the first model for video that's good at frozen evaluations, which means we do all of our self-supervised pre-training on the encoder and the predictor, and then we don't touch those parts of the model anymore."15 This frozen evaluation capability means the same pretrained model works across action classification, object interaction recognition, and activity localization.

VL-JEPA: Bringing Language into the Picture

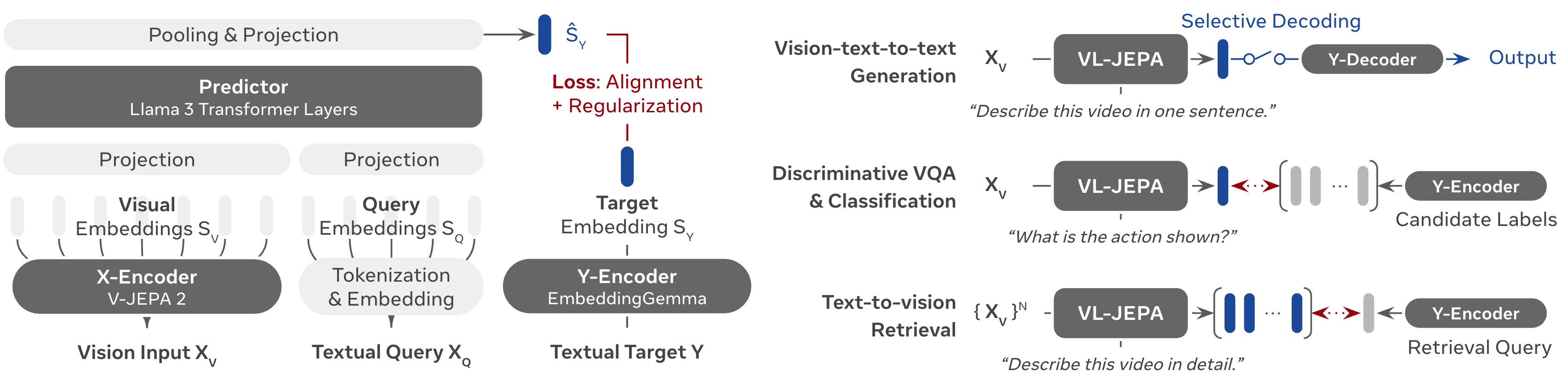

VL-JEPA completes the progression by combining the V-JEPA video encoder with language understanding. The architecture uses a frozen V-JEPA 2 vision encoder paired with a trainable transformer predictor.

Figure 4: VL-JEPA architecture predicting continuous text embeddings from visual input. The frozen V-JEPA encoder provides visual representations while the transformer predictor outputs embeddings rather than discrete tokens. Source: VL-JEPA Paper

Figure 4: VL-JEPA architecture predicting continuous text embeddings from visual input. The frozen V-JEPA encoder provides visual representations while the transformer predictor outputs embeddings rather than discrete tokens. Source: VL-JEPA Paper

The critical innovation is in how language is handled. Rather than generating text tokens autoregressively, VL-JEPA predicts continuous text embeddings. "By learning in an abstract representation space, the model focuses on task-relevant semantics while abstracting away surface-level linguistic variability."16

This design choice has profound implications. When predicting embeddings rather than tokens, the model can express "the answer is somewhere in this semantic region" rather than committing to exact words. The model doesn't need to decide between "a dog" and "the dog," between "running" and "runs." It predicts the semantic content, and that content can be decoded into whatever surface form is needed.

This embedding-based approach yields dramatic parameter efficiency. VL-JEPA achieves "comparable performance to classical VLMs (InstructBLIP, QwenVL) with only 1.6B parameters"17, representing roughly a 50% parameter reduction compared to models with similar capabilities.

Adaptive Selective Decoding

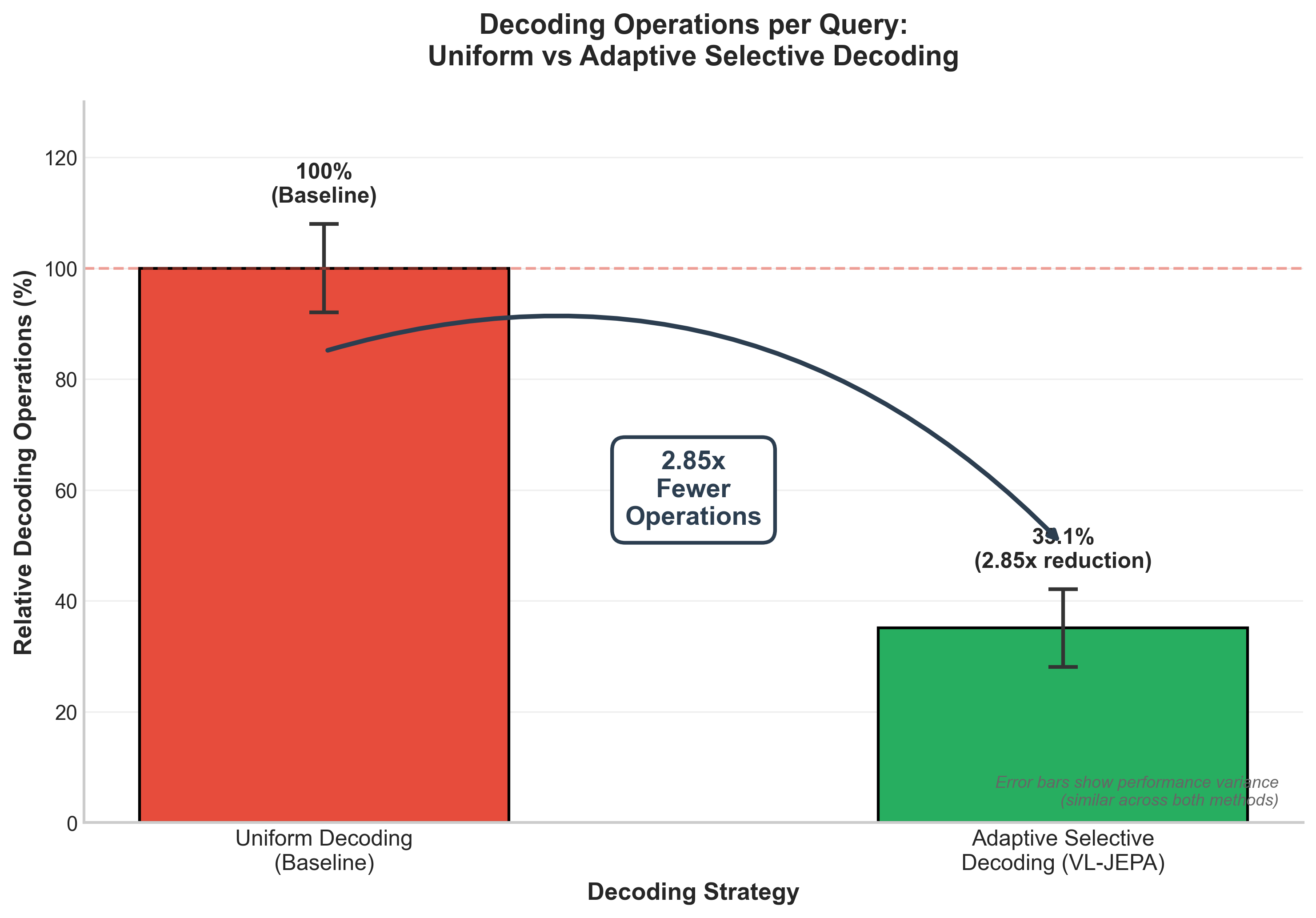

The inference speedup comes from adaptive selective decoding. Instead of producing a fixed number of embedding predictions, VL-JEPA dynamically determines how many predictions are needed based on task complexity.

Traditional approaches might predict 10 embeddings for every query, whether the query demands "yes" or "the cat is sitting on a red cushion near the window." VL-JEPA instead learns to predict only as many embeddings as needed.

The mechanism "reduces the number of decoding operations by 2.85x while maintaining similar performance compared to non-adaptive uniform decoding."18 For simple questions like "What color is the ball?", the model might need only a few embedding predictions. For complex descriptions, it allocates more decoding capacity.

Figure 5: VL-JEPA's Adaptive Selective Decoding reduces decoding operations by 2.85x compared to uniform decoding while maintaining similar performance variance. Data source: VL-JEPA Paper

Figure 5: VL-JEPA's Adaptive Selective Decoding reduces decoding operations by 2.85x compared to uniform decoding while maintaining similar performance variance. Data source: VL-JEPA Paper

This draws conceptually from speculative decoding research. Google demonstrated that "speculative decoding can collapse multiple waiting periods into one. By using a fast draft mechanism to speculate two candidate tokens then verifying them all in a single forward pass, the model can generate three tokens in the time it previously took to generate one."19 VL-JEPA applies similar parallelization principles but operates in embedding space rather than token space.

Why Representation Space Matters

The shift from token prediction to embedding prediction reflects a deeper insight about language and meaning.

Tokens are artifacts of how we write language, not how we think it. The word "cat" encoded as token 12847 doesn't inherently relate to token 12848 representing "dog" the way their meanings relate. Token space is arbitrary; embedding space is geometric.

In embedding space, similar concepts cluster together. "Cat," "feline," and "kitty" occupy nearby regions. The model can predict a region rather than committing to a specific point. This matches how humans often think: we know the meaning we want to express before we commit to exact words.

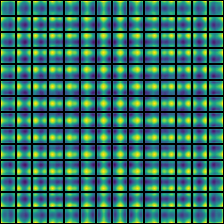

Figure 6: Attention patterns in Vision Transformers reveal that the model naturally learns to attend to semantic features. Self-attention allows ViT to integrate information across the entire image even in the lowest layers. Source: ViT Paper

Figure 6: Attention patterns in Vision Transformers reveal that the model naturally learns to attend to semantic features. Self-attention allows ViT to integrate information across the entire image even in the lowest layers. Source: ViT Paper

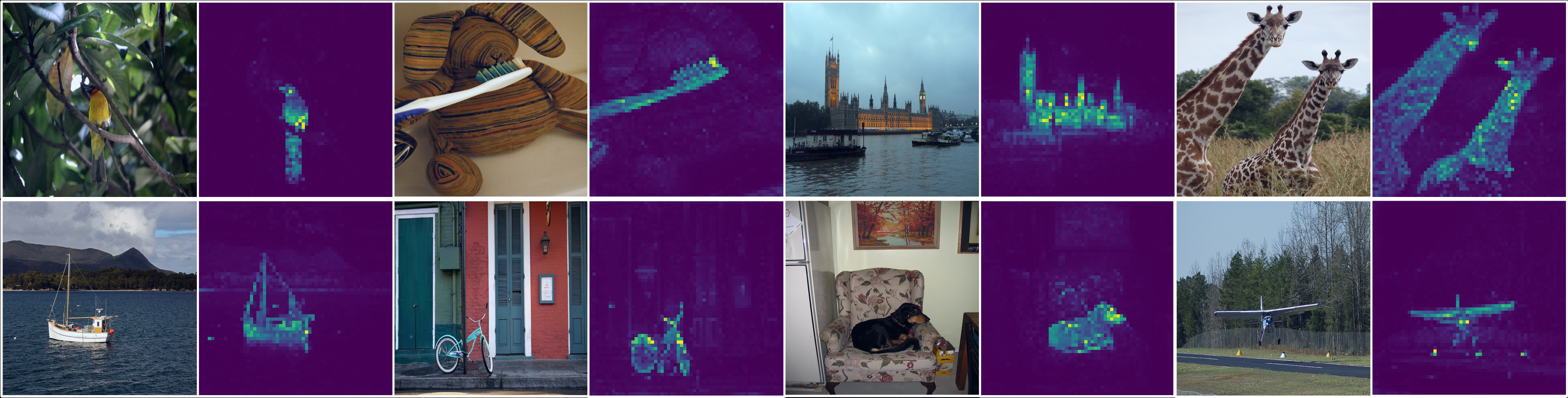

"Making these predictions in the abstract representation space is important because it allows the model to focus on the higher-level conceptual information of what the video contains without worrying about the kind of details that are most often unimportant for downstream tasks."20

The training dynamics also improve. "In contrast to Joint-Embedding Architectures, JEPAs do not seek representations invariant to a set of hand-crafted data augmentations, but instead seek representations that are predictive of each other when conditioned on additional information z."21 The model learns what matters for prediction rather than memorizing specific augmentation patterns.

The Self-Supervised Foundation

VL-JEPA's efficiency partly stems from its self-supervised foundation. The V-JEPA 2 vision encoder learns from unlabeled video, requiring no human annotation.

Figure 7: DINO demonstrates that Vision Transformers naturally learn semantic features through self-supervised learning, without explicit supervision. These attention patterns emerge purely from predicting representations. Source: DINO Paper

Figure 7: DINO demonstrates that Vision Transformers naturally learn semantic features through self-supervised learning, without explicit supervision. These attention patterns emerge purely from predicting representations. Source: DINO Paper

"Because it takes a self-supervised learning approach, V-JEPA is pre-trained entirely with unlabeled data. Labels are only used to adapt the model to a particular task after pre-training."22

This has practical implications. Labeled data is expensive. Video annotation is especially expensive since it requires temporal understanding, not just frame-by-frame labeling. By learning representations from raw video, VL-JEPA can use the vast amounts of unlabeled video available online.

V-JEPA 2, which serves as VL-JEPA's vision backbone, scales to significant capacity. The "Largest Model Size: ViT-g/16 (1B Params)" trains on "VideoMix22M (22 million videos) = VideoMix2M + YT-Temporal-1B (19 M videos, 16M hours) + ImageNet (1M images)."23

The World Model Perspective

Yann LeCun has consistently framed JEPA as progress toward world models. "The fundamental part of LeCun's vision is the concept of world models, which are internal representations of how the world functions."24

"The predictor in this Joint Embedding Predictive Architecture serves as an early physical world model: You don't have to see everything that's happening in the frame, and it can tell you conceptually what's happening there."25

This interpretation connects to broader questions about what AI systems actually understand. LeCun has argued that "LLMs have no common sense: LLMs have limited knowledge of the underlying reality and make strange mistakes called hallucinations."26 Token prediction optimizes for surface statistics of language, not understanding of the world that language describes.

"The idea behind I-JEPA is to predict missing information in an abstract representation that's more akin to the general understanding people have."27 Whether this leads to genuine world models remains an open question, but the architectural choice aligns with that goal.

Benchmarks and Practical Performance

VL-JEPA demonstrates strong results across vision-language benchmarks. The model achieves competitive performance on VQA (Visual Question Answering), video retrieval, and open-vocabulary classification tasks with significantly fewer parameters than baseline approaches.

Figure 8: VL-JEPA performance across benchmark tasks, demonstrating competitive results with reduced parameter counts. Source: VL-JEPA Paper

Figure 8: VL-JEPA performance across benchmark tasks, demonstrating competitive results with reduced parameter counts. Source: VL-JEPA Paper

The zero-shot capabilities are particularly notable. The model demonstrates "strong zero-shot capabilities on video classification and retrieval benchmarks"28 without task-specific fine-tuning. This transfer ability validates the quality of learned representations.

The robotics domain provides additional validation. "V-JEPA 2 proves to be an effective world model when applied to robotics planning. This robotics application brings JEPA closer to the brain framework introduced in the original JEPA position paper."29

Current Limitations

VL-JEPA represents significant progress, but limitations remain. Honest assessment is essential.

What VL-JEPA Cannot (Yet) Do:

- Long-form generation: Producing paragraphs of coherent text remains harder than for autoregressive models

- Fine-grained linguistic control: Controlling style, tone, and specific phrasing is less direct

- Extended temporal horizons: "This is predicting gaps in short videos. It does not predict across time. Human learning is across the time dimension."30

- Open-ended dialogue: Multi-turn conversation requires extensions not yet fully developed

The embedding prediction approach trades some flexibility for efficiency. Autoregressive models can generate arbitrary-length responses with arbitrary content. Embedding prediction systems require the output space to be defined during training.

Integration with instruction-following capabilities also requires additional work. While VL-JEPA excels at discriminative tasks and retrieval, open-ended conversation still benefits from generative approaches.

Looking Forward

The VL-JEPA results suggest a broader shift may be coming in how vision-language models are built.

The efficiency gains are substantial enough to change deployment economics. A 2.85x speedup in decoding, combined with 50% parameter reduction, opens possibilities for real-time applications, mobile deployment, edge computing, and cost-sensitive production systems.

The architectural principles extend beyond the specific VL-JEPA implementation. Any vision-language task where the output can be represented as continuous embeddings might benefit from similar approaches. Retrieval, classification, similarity matching, and grounded reasoning are natural fits.

Future extensions might include hierarchical prediction, where "several JEPAs could be combined into a multistep/recurrent JEPA or stacked into a Hierarchical JEPA that could be used to perform predictions at several levels of abstraction and several time scales."31 Multimodal expansion incorporating audio, extended temporal prediction horizons for planning tasks, and deeper integration with robotics planning all represent active research directions.

"Our goal is to build advanced machine intelligence that can learn more like humans do, forming internal models of the world around them to learn, adapt, and forge plans efficiently in the service of completing complex tasks."32

The question is not whether embedding prediction will replace autoregressive generation entirely. For tasks requiring precise linguistic output, the ability to generate specific token sequences will remain valuable. But for tasks centered on understanding, for grounding language in visual reality, for building efficient systems that know what they mean before they say it, VL-JEPA points toward a compelling alternative.

Sometimes the best way to generate the right words is to first understand what you want to say.

References

Footnotes

-

Chen, D., et al. (2024). VL-JEPA: Joint Embedding Predictive Architecture for Vision-language. arXiv:2512.10942 ↩

-

NVIDIA Developer Blog. (2023). An Introduction to Speculative Decoding for Reducing Latency in AI Inference. https://developer.nvidia.com/blog/an-introduction-to-speculative-decoding-for-reducing-latency-in-ai-inference/ ↩

-

Google Research. (2024). Looking Back at Speculative Decoding. https://research.google/blog/looking-back-at-speculative-decoding/ ↩

-

Meta AI Blog. (2023). I-JEPA: The first AI model based on Yann LeCun's vision for more human-like AI. https://ai.meta.com/blog/yann-lecun-ai-model-i-jepa/ ↩

-

Assran, M., et al. (2023). Self-Supervised Learning from Images with a Joint-Embedding Predictive Architecture. arXiv:2301.08243 ↩

-

Assran, M., et al. (2023). I-JEPA Paper, arXiv:2301.08243 ↩

-

Turing Post. (2024). What is JEPA? https://www.turingpost.com/p/jepa ↩

-

Assran, M., et al. (2023). I-JEPA Paper, arXiv:2301.08243 ↩

-

Assran, M., et al. (2023). I-JEPA Paper, arXiv:2301.08243 ↩

-

Assran, M., et al. (2023). I-JEPA Paper, arXiv:2301.08243 ↩

-

Meta AI Blog. (2024). V-JEPA: The next step toward advanced machine intelligence. https://ai.meta.com/blog/v-jepa-yann-lecun-ai-model-video-joint-embedding-predictive-architecture/ ↩

-

Bandaru, R. (2024). Deep Dive into Yann LeCun's JEPA. https://rohitbandaru.github.io/blog/JEPA-Deep-Dive/ ↩

-

Meta AI Blog. (2024). V-JEPA Blog. ↩

-

Meta AI Blog. (2024). V-JEPA Blog. ↩

-

Meta AI Blog. (2024). V-JEPA Blog. ↩

-

Chen, D., et al. (2024). VL-JEPA Paper, arXiv:2512.10942 ↩

-

Chen, D., et al. (2024). VL-JEPA Paper, arXiv:2512.10942 ↩

-

Chen, D., et al. (2024). VL-JEPA Paper, arXiv:2512.10942 ↩

-

Google Research. (2024). Looking Back at Speculative Decoding. ↩

-

Meta AI Blog. (2024). V-JEPA Blog. ↩

-

Assran, M., et al. (2023). I-JEPA Paper, arXiv:2301.08243 ↩

-

Meta AI Blog. (2024). V-JEPA Blog. ↩

-

Bandaru, R. (2024). Deep Dive into JEPA. ↩

-

Turing Post. (2024). What is JEPA? ↩

-

Meta AI Blog. (2024). V-JEPA Blog. ↩

-

Turing Post. (2024). What is JEPA? ↩

-

Meta AI Blog. (2023). I-JEPA Blog. ↩

-

Chen, D., et al. (2024). VL-JEPA Paper, arXiv:2512.10942 ↩

-

Bandaru, R. (2024). Deep Dive into JEPA. ↩

-

Bandaru, R. (2024). Deep Dive into JEPA. ↩

-

Turing Post. (2024). What is JEPA? ↩

-

Meta AI Blog. (2024). V-JEPA Blog. ↩