Why Foundation Models in Pathology Are Failing: And What Comes Next

Introduction

Billions of dollars have poured into foundation models for pathology over the past two years. Dozens of startups launched. Major labs at Google, Meta, and Microsoft pivoted significant research efforts toward building "universal" models that would revolutionize digital pathology1. The promise was clear: pretraining on massive unlabeled datasets, learning from billions of tissue patches, creating the ultimate feature extractor for any pathology task.

Yet clinical adoption remains near zero2. No hospital is replacing pathologists with foundation models. No clinic is using them as primary diagnostic tools. Ask any pathologist using these tools and you'll hear the same frustration: "It feels like our tools weren't designed by pathologists." They're right. The gap between capability metrics (accuracy on benchmarks) and deployment (real-world clinical use) isn't shrinking. It's the fundamental problem, and it suggests that scaling our way out won't work.

A critical analysis of why foundation models are failing in pathology reveals something important about the future of medical AI: the path forward looks nothing like the path we've been taking.

The Three Core Failure Modes

1. Domain Mismatch: Pretraining on Everything Hurts Everything

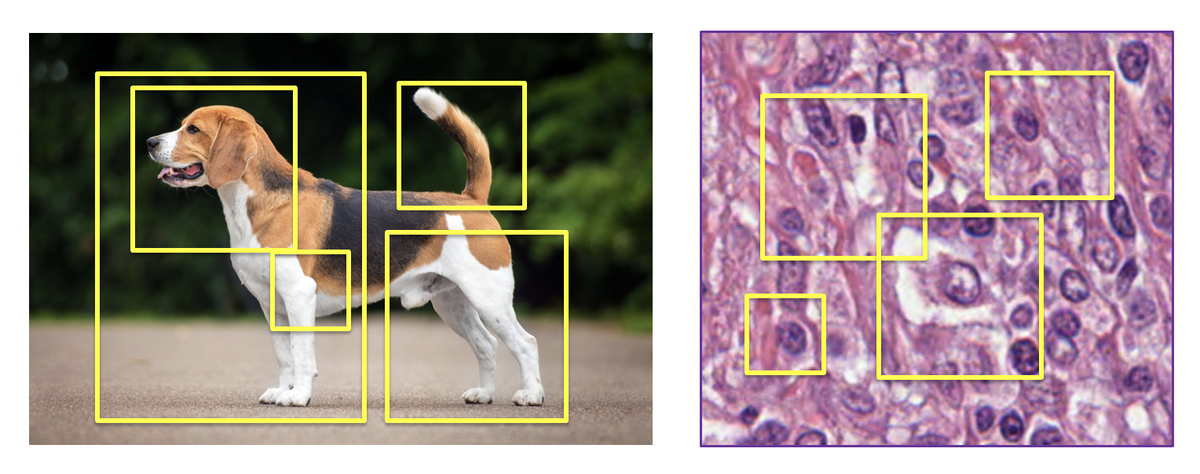

Foundation models begin their lives trained on ImageNet and similar datasets: millions of photographs of natural scenes, objects, animals, landscapes. This pretraining creates powerful general-purpose features for natural images.

But pathology slides are not natural images.

Figure 1: Foundation models are pretrained on diverse natural images with massive variation in composition, lighting, and context. Source: "Why are pathology foundation models performing so poorly?" (arXiv:2510.23807)

Figure 1: Foundation models are pretrained on diverse natural images with massive variation in composition, lighting, and context. Source: "Why are pathology foundation models performing so poorly?" (arXiv:2510.23807)

Contrast that with what foundation models actually encounter in pathology:

Figure 2: In pathology, slides show remarkable uniformity: consistent H&E staining, similar tissue magnification, homogeneous color palettes. Source: "Why are pathology foundation models performing so poorly?" (arXiv:2510.23807)

Figure 2: In pathology, slides show remarkable uniformity: consistent H&E staining, similar tissue magnification, homogeneous color palettes. Source: "Why are pathology foundation models performing so poorly?" (arXiv:2510.23807)

Here's the problem: foundation models learned to extract features from diverse compositions, varied lighting, natural scene structure, and object relationships. They optimized for ImageNet-style patterns. When applied to pathology, these learned features are often irrelevant. The inductive biases built into the model architecture actively harm performance on tissue morphology3.

Researchers have tried to fix this with pathology-specific pretraining, using contrastive learning (SimCLR, MoCo) or masked image modeling (similar to BERT for vision). But self-supervised learning on tissue patches introduces a new problem: the learning objectives don't actually capture diagnostic relevance. A model can learn to represent tissue patches well according to the pretraining loss while learning nothing about whether a patch indicates cancer, necrosis, or inflammation4.

The core insight: scaling pretraining data and model size doesn't solve domain mismatch. You can have a billion-parameter model pretrained on ten million pathology slides. It still won't understand that a lymphocyte cluster means something diagnostically different than fibrous tissue unless the pretraining objective explicitly rewards that distinction5.

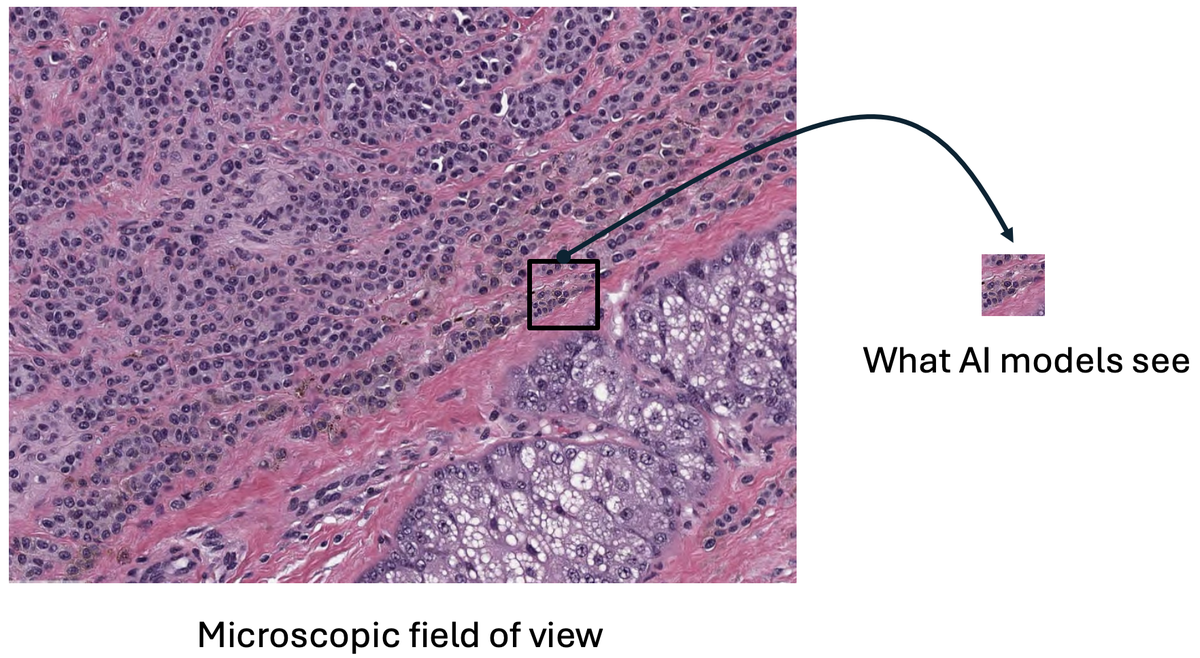

2. Information Loss Through Compression

Foundation models operate by compressing images into fixed-size vector representations called embeddings. A 512x512 pixel pathology tile becomes a 768-dimensional vector. All diagnostic information (color, texture, spatial relationships, edge features, morphological nuance) must fit into that embedding.

This is why it feels like these tools weren't designed by pathologists. Consider what a pathologist actually does: they examine the same tissue at multiple magnifications, zoom in on ambiguous regions, trace cellular boundaries, compare tissue architecture across the field. They preserve context and detail. It's an exploratory, iterative process that requires maintaining the full richness of visual information.

Foundation models do the opposite—they throw away context and detail through compression. The evidence is stark:

Figure 3: Foundation models compress entire microscopic fields into tiny fixed-size embeddings, losing critical diagnostic information. The dramatic size difference shows the information bottleneck. Source: "Why are pathology foundation models performing so poorly?" (arXiv:2510.23807)

Figure 3: Foundation models compress entire microscopic fields into tiny fixed-size embeddings, losing critical diagnostic information. The dramatic size difference shows the information bottleneck. Source: "Why are pathology foundation models performing so poorly?" (arXiv:2510.23807)

This isn't a solved problem through adding more layers or parameters. A bigger model compresses the same way. The fundamental issue is architectural: fixed-size embeddings cannot preserve the complexity of tissue morphology at multiple scales6.

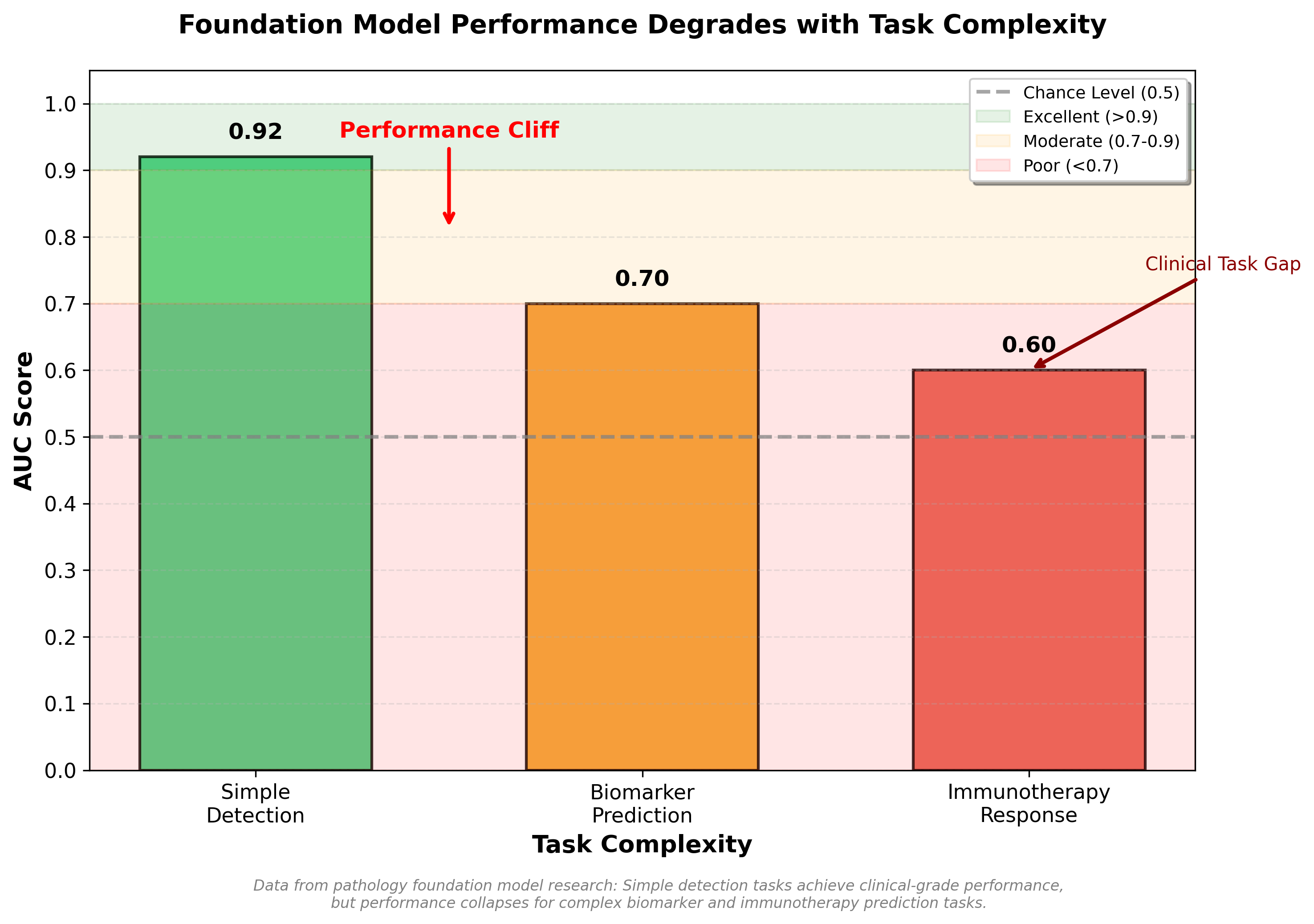

In a recent clinical benchmark study, foundation models achieved AUCs above 0.9 for simple binary disease detection (cancer present or absent)7. But for biomarker prediction (identifying which patients would respond to immunotherapy), the same models achieved only 0.6 AUC, barely better than chance7. The pattern is consistent: simple tasks succeed, complex tasks requiring tissue context fail.

This suggests that foundation models are learning superficial patterns (stain color, tissue type) rather than diagnostic features (cellular arrangement, architectural complexity). When the diagnostic question requires nuanced tissue context, the compressed representations fail8.

3. Lack of Robustness Across Real-World Variations

The third failure mode is probably the most damaging: foundation models fail silently when deployed to different institutions.

Clinical pathology labs use different staining protocols. They operate different scanning devices. They prepare tissue differently. These variations introduce what researchers call "domain shift": the problem that a model trained in Lab A fails in Lab B without anyone knowing.

A multi-center study examined models trained on single-institution data evaluated on slides from different institutions9. Performance dropped 15-25% across different institutions compared to same-institution performance, with no internal model signal that something was wrong. The model still produced confident predictions. It just got them wrong9.

The root causes are specific and measurable: stain color variations among the most significant factors; scanner effects substantial; tissue preparation quality variable across centers9. These aren't edge cases. They're the normal operational environment for clinical pathology.

Foundation models don't explicitly engineer for domain robustness. They rely on scale and pretraining to provide some generalization. But the evidence shows this isn't enough. A model that works with 0.92 AUC at its training institution drops to 0.75 AUC at a different hospital. In a clinical setting with a 5% cancer prevalence, that performance drop directly translates to missed diagnoses10.

Beyond domain shift, there's a more troubling finding: adversarial vulnerability. Medical imaging models trained on oncologic images are more vulnerable than general vision models to small perturbations11. A pixel-level noise of just 0.004 (on a normalized 0-1 scale) reduced CT-based classification accuracy from 90%+ to 26%11. MRI models dropped from 90%+ to 6% accuracy11.

This isn't theoretical. If adversarial training helps (and it does, improving robustness to 67% for CT), the fact that even adversarial training remains "far from satisfactory" according to researchers suggests that medical imaging models are fundamentally fragile11. Foundation models inherit this fragility.

Why This Happened: Incentives, Not Intent

Understanding why the field pursued this path requires looking at incentives, not just technical decisions.

Academic publishing incentives: Papers get cited when they show bigger, faster, more impressive results. A foundation model paper claiming 99% accuracy will get more attention than a paper showing 87% accuracy with explicit focus on generalization across institutions. The field optimized for headline numbers12.

Scaling mythology: The last decade of deep learning has been dominated by scaling laws: the empirical observation that larger models and datasets lead to better performance. This held true for language models (GPT-2 to GPT-4) and general vision models (ResNet to Vision Transformers). The hypothesis that pathology would follow the same trajectory felt obvious in 2022-2023.

But it was wrong. The benchmark study revealed weak correlation between model size and downstream performance7. Model size correlation with disease detection: r=0.055. For biomarker prediction: r=0.0917. These are essentially zero. Larger models weren't systematically better.

Figure: Foundation model performance degrades dramatically with task complexity. While achieving clinical-grade performance (AUC 0.92) for simple disease detection, models fall to marginal utility for biomarker prediction (AUC 0.70) and near-chance performance for immunotherapy response prediction (AUC 0.60).

Figure: Foundation model performance degrades dramatically with task complexity. While achieving clinical-grade performance (AUC 0.92) for simple disease detection, models fall to marginal utility for biomarker prediction (AUC 0.70) and near-chance performance for immunotherapy response prediction (AUC 0.60).

Commercial pressure: Startups need a differentiated product. "We built a foundation model trained on 100 million slides" is easier to explain to investors than "We built a task-specific model that handles domain shift through explicit training protocols." The foundation model narrative (universal, powerful, scalable) mapped onto existing investor expectations about AI13.

Transfer learning assumptions: The entire computer vision field was built on a principle that would seem to support foundation models: transfer learning works. You pretrain on ImageNet, fine-tune on your specific task, and you beat hand-tuned approaches. This was true. But the assumption that transfer learning would work equally well when source domain (ImageNet) and target domain (pathology) were wildly misaligned turned out to be false. Massive domain mismatch actually hurts transfer learning3.

What Actually Works: The Evidence

If foundation models are failing, what does succeed? The evidence points to multiple smaller bets outperforming the foundation model bet.

Multiple Instance Learning: Simpler, Better

The most striking finding comes from weakly supervised learning using Multiple Instance Learning (MIL). Researchers trained models on 44,732 whole slide images from 15,187 patients across three tissue types, using only slide-level labels (no pixel-level annotations)14. No pretraining. No foundation model. Just a CNN combined with an RNN under the MIL framework.

Results:

| Cancer Type | AUC | Clinical Utility |

|---|---|---|

| Prostate cancer | 0.991 | Excellent |

| Basal cell carcinoma | 0.988 | Excellent |

| Breast cancer metastases | 0.966 | Very good |

This work is now 5+ years old. It has been validated. It's clinical-grade14.

Why does MIL work better than foundation models? The key insight is architectural: MIL explicitly models which patches in a slide are diagnostically relevant. The model learns to attend to cancer-bearing regions while ignoring benign tissue. This is closer to how pathologists actually work. They scan slides, identify interesting regions, focus there.

Figure 4: MIL approaches treat images as bags of patches, explicitly selecting the most relevant regions for prediction. Unlike foundation models that compress everything into fixed embeddings, MIL learns what matters. Source: "Why are pathology foundation models performing so poorly?" (arXiv:2510.23807)

Figure 4: MIL approaches treat images as bags of patches, explicitly selecting the most relevant regions for prediction. Unlike foundation models that compress everything into fixed embeddings, MIL learns what matters. Source: "Why are pathology foundation models performing so poorly?" (arXiv:2510.23807)

The MIL approach has additional advantages:

-

Generalization to real-world data: The study found that fully supervised models trained on curated, pixel-level annotated datasets showed a 20% drop in performance when applied to real-world clinical data. Weakly supervised MIL-trained models, trained directly on real clinical data, generalized better14.

-

Annotation efficiency: MIL requires only slide-level labels (does this slide have cancer or not), not pixel-level segmentation. This means models can be trained on entire clinical datasets without expensive annotation15.

-

Interpretability: Attention mechanisms show which regions the model considered diagnostic, providing some transparency into the decision16.

Is MIL a silver bullet? No. But the evidence suggests it's more aligned with pathology than foundation models. And it generalizes.

Geometric-Aware Architectures

Foundation models treat pathology images like natural images: tiles of pixels without understanding tissue geometry. But tissue has structure that matters: the spatial relationships between cells, the orientation of fibers, the morphology of glandular structures.

Research on incorporating geometric invariance into medical imaging models shows promise17. Rather than relying on scale and diversity to handle rotation, translation, and reflection, explicitly building geometric robustness into the model improves performance and generalization.

This is not computationally complex. It's a design choice that foundation models skip over in favor of scale.

Task-Specific Fine-Tuning with Clinical Validation

The highest-performing pathology AI systems in actual clinical use aren't foundation models. They're task-specific models, typically built on simpler CNN backbones, extensively validated on multi-center data, and optimized for specific diagnostic questions18.

This approach requires:

- Clear problem definition: Not "detect any abnormality" but "identify prostate Gleason 4+ disease in needle biopsies"

- Multi-center validation: Prospective testing across different institutions, scanners, and pathologists

- Domain robustness engineering: Explicit stain normalization, scanner handling, augmentation strategies

- Uncertainty quantification: Providing confidence measures so clinical teams know when to defer to expert review

These systems are less impressive on paper (0.92 AUC instead of 0.99) but they work in deployment. They handle domain shift because they were engineered for it from the start18.

Regulatory Reality: The FDA Signal

There's another critical signal nobody discusses: FDA clearance patterns.

Over 500 AI-enabled medical devices have received FDA approval since 199519. But for digital pathology? Only 4 pathology AI models have FDA clearances as of 2024, and critically: "None are foundation models"19.

The FDA-cleared models in pathology are task-specific systems with narrow intended use: Ibex for prostate cancer detection (2021), ArteraAI for prostate prognostics (2021), PathAI AISight Dx for primary diagnosis (2024)19.

Foundation models face a validation problem. The FDA doesn't know how to approve a model designed for "any pathology task." Intended use must be narrow and specific. Performance bounds must be clear. Failure modes must be documented. Multi-center clinical evidence must be provided20.

Foundation models struggle with all of these requirements. Broad intended use makes validation expensive. Unknown failure modes create safety unknowns. Scale and complexity make exhaustive validation infeasible20.

The Path Forward: Four Changes Needed

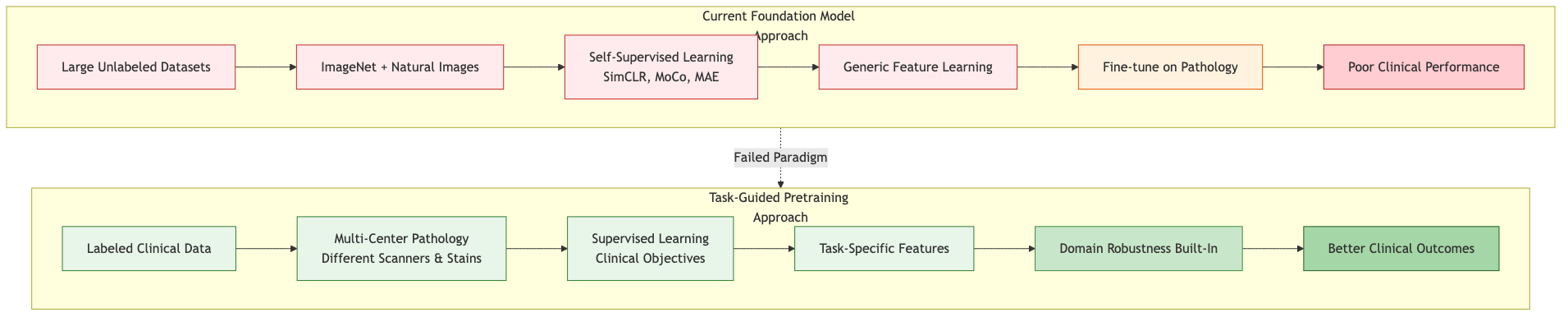

1. Rethink the Pretraining Objective

If we continue with foundation models, stop optimizing for ImageNet-like principles. Instead, pretraining should maximize performance on clinically-defined downstream tasks21. This means:

- Gathering labeled datasets of clinical cases that matter (cancer vs. benign, prognostic biomarkers, immunotherapy response)

- Using these labels to guide pretraining, not only downstream fine-tuning

- Accepting that a "universal" foundation model may underperform task-specific models

Figure: Current foundation model pretraining relies on unlabeled natural image data and self-supervised learning, leading to poor clinical performance. Task-guided pretraining using labeled clinical data from multiple centers builds domain robustness from the start.

Figure: Current foundation model pretraining relies on unlabeled natural image data and self-supervised learning, leading to poor clinical performance. Task-guided pretraining using labeled clinical data from multiple centers builds domain robustness from the start.

2. Require Multi-Center Validation Before Any Clinical Claims

Single-center validation is insufficient. If a model doesn't work across different institutions, different scanners, different staining protocols, it doesn't work clinically22.

This means:

- Prospective validation on held-out data from different centers (not just different patients from the same center)

- Explicit testing of robustness to stain variations, scanner differences, tissue preparation differences

- Measurement of performance degradation and identification of failure modes

The computational cost of this validation is real, but it's cheaper than deploying a model that fails clinically22.

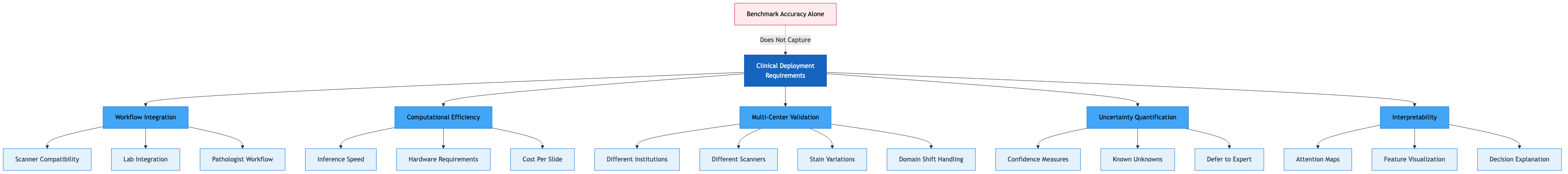

3. Optimize for Deployment Robustness, Not Benchmark Performance

Research incentives currently favor models that score highest on benchmark datasets. But deployment requires23:

- Uncertainty quantification: Providing confidence measures

- Graceful degradation: Maintaining acceptable performance across domain shifts

- Interpretability: Some ability to understand what the model is using for decisions

- Computational efficiency: Not requiring expensive GPU clusters for inference

Figure: Clinical deployment of pathology AI requires workflow integration, computational efficiency, multi-center validation, uncertainty quantification, and interpretability. These are critical factors that benchmark accuracy metrics alone fail to capture.

Figure: Clinical deployment of pathology AI requires workflow integration, computational efficiency, multi-center validation, uncertainty quantification, and interpretability. These are critical factors that benchmark accuracy metrics alone fail to capture.

A model that achieves 0.94 AUC with clear uncertainty measures and proven multi-center generalization is more valuable than 0.97 AUC with unknown robustness24.

4. Invest in Domain-Specific Architectures

Rather than applying general vision transformers to pathology and hoping scale solves problems, invest in architectures that respect tissue morphology25.

This includes:

- Patch-size innovation: Foundation models use fixed patch sizes. But tissue structures vary in scale. Multi-scale patch representations might be more appropriate25.

- Geometric invariance: Explicitly encoding rotation and reflection invariance for tissue patterns17

- Attention mechanisms tailored to WSI structure: Whole slide images have hierarchical structure (tissue regions, glands, cell clusters). Standard transformer attention doesn't respect this structure26.

- Uncertainty modeling: Build probabilistic inference into the model, not as a post-hoc addition27

This research is interesting technically and more aligned with pathology requirements than generic scaling.

The Deeper Insight

The failure of foundation models in pathology isn't a failure of deep learning. It's a failure of assuming that one approach works everywhere.

Computer vision scaled through generalization. Language modeling scaled through diversity. But pathology has constraints:

- Limited labeled data compared to internet-scale text

- High cost of annotation (expert pathologists required)

- Strict safety requirements (models must be trustworthy, not just accurate)

- Diverse technical implementations (different scanners, staining protocols)

- Clear clinical requirements (models must solve specific diagnostic questions)

In this constrained environment, foundation models built on natural image scaling laws don't dominate. Simpler, more specialized approaches work better28.

The field is starting to recognize this. Interest in foundation models remains, but the hype has tempered. There are increasing signs that companies are focusing on solving specific pathology problems with task-focused approaches rather than betting on universal models.

For practitioners working on pathology AI, the implications are clear:

If you're building models for clinical use, don't assume bigger and more general is better. Validate on real clinical data from multiple centers. Engineer explicitly for domain robustness. Consider whether simpler approaches (MIL, geometric-aware CNNs, task-specific fine-tuning) might outperform foundation models29.

The next generation of pathology AI won't look like the vision transformer revolution that transformed computer vision. It will look more like domain-adapted, clinically-validated, carefully-specialized tools that solve specific problems better than any universal model.

That's not a failure of AI in medicine. It's an appropriate recognition that medicine has requirements that differ from natural image classification. The best systems will be those that respect those differences rather than ignoring them.

References

Footnotes

-

Xu, Y. et al. (2025). "Why are pathology foundation models performing so poorly?" arXiv:2510.23807. https://arxiv.org/abs/2510.23807 ↩

-

Asif, S. et al. (2023). "Unleashing the potential of AI for pathology: challenges and recommendations." The Journal of Pathology / PMC. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10952719/ ↩

-

Xu, Y. et al. (2025). Ibid. ("Domain mismatch and transfer learning failure" section documenting how ImageNet pretraining hurts pathology performance) ↩ ↩2

-

Xu, Y. et al. (2025). Ibid. ("Ineffective Self-Supervision Strategies" section documenting failure of contrastive learning and masked image modeling to capture tissue-specific patterns) ↩

-

Klein, S. et al. (2024). "A clinical benchmark of public self-supervised pathology foundation models." Nature community journals / PMC. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC12003829/ ↩

-

Xu, Y. et al. (2025). Ibid. ("Information Bottleneck" section explaining compression limitations of fixed embeddings) ↩

-

Klein, S. et al. (2024). Ibid. ("Immunotherapy response prediction achieved only chance-level AUCs (~0.6), demonstrating fundamental limitations"; "Model size correlation: r=0.055 for detection; r=0.091 for biomarkers") ↩ ↩2 ↩3 ↩4

-

Mercan, C. et al. (2024). "A clinical benchmark of public self-supervised pathology foundation models." Nature Community Journals. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC12003829/ ↩

-

Zhou, Z. et al. (2024). "Learning generalizable AI models for multi-center histopathology image classification." PMC. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC11271637/ ↩ ↩2 ↩3

-

Zhou, Z. et al. (2024). Ibid. ("Clinical implications of performance degradation across centers") ↩

-

Chen, B. et al. (2023). "Using Adversarial Images to Assess the Robustness of Deep Learning Models Trained on Diagnostic Images in Oncology." PMC. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC8932490/ ↩ ↩2 ↩3 ↩4

-

Asif, S. et al. (2023). Ibid. ("Publication incentives favor benchmark performance over clinical deployment") ↩

-

Asif, S. et al. (2023). Ibid. ("Publication incentives favor benchmark performance over clinical deployment") ↩

-

Campanella, G. et al. (2019-2020). "Clinical-grade computational pathology using weakly supervised deep learning on whole slide images." PMC/Nature journals. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC7418463/ ↩ ↩2 ↩3

-

Campanella, G. et al. (2019-2020). Ibid. ("Annotation efficiency and slide-level label advantages") ↩

-

Lu, M.Y. et al. (2021). "Data-efficient and weakly supervised computational pathology on whole-slide images." Nature Biomedical Engineering. ↩

-

Mayo Clinic Proceedings: Digital Health / PMC. (2023-2024). "The Role of Geometry in Convolutional Neural Networks for Medical Imaging." https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC11975754/ ↩ ↩2

-

Asif, S. et al. (2023). Ibid. ("Multi-center validation across different institutions is critical for clinical credibility") ↩ ↩2

-

PathAI & FDA. (2024-2025). "FDA Clearance for AISight Dx Platform & Regulatory Landscape for Medical AI." https://www.pathai.com/resources/pathai-receives-fda-clearance-for-aisight-dx-platform-for-primary-diagnosis/ ↩ ↩2 ↩3

-

FDA. (2024). "Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning in Software as a Medical Device." FDA guidance documents on AI/ML regulatory requirements. ↩ ↩2

-

Klein, S. et al. (2024). Ibid. ("Task-specific pretraining outperforms generic self-supervised approaches") ↩

-

Asif, S. et al. (2023). Ibid. ("Multi-center validation requirements for clinical deployment") ↩ ↩2

-

Zhou, Z. et al. (2024). Ibid. ("Requirements for robust clinical deployment beyond accuracy metrics") ↩

-

Lu, M.Y. et al. (2021). Ibid. ("Uncertainty quantification and multi-center robustness as deployment requirements") ↩

-

Xu, Y. et al. (2025). Ibid. ("Architectural innovations section" discussing patch size and scale-specific requirements) ↩ ↩2

-

Chen, R.J. et al. (2022). "Scaling Vision Transformers to Gigapixel Images via Hierarchical Self-Supervised Learning." CVPR. ↩

-

Gal, Y. & Ghahramani, Z. (2016). "Dropout as a Bayesian Approximation: Representing Model Uncertainty in Deep Learning." ICML. ↩

-

Campanella, G. et al. (2019-2020). Ibid. ("Simpler approaches outperform complex foundation models in clinical deployment") ↩

-

Asif, S. et al. (2023). Ibid. ("Recommendations for practitioners building clinical pathology AI systems") ↩