When the Algorithm Can't Explain Itself: ML Interpretability in Precision Oncology

Your deep learning model just flagged a patient as unlikely to respond to immunotherapy. The oncologist asks why. You point to the AUC of 0.76, the thousands of training samples, the external validation across 10 phase 3 trials. She nods, then asks again: "But why this patient?"

This question sits at the heart of precision oncology's most uncomfortable tension. Machine learning models now outperform FDA-approved biomarkers in predicting treatment response, but the models that perform best often resist explanation. If we cannot answer the oncologist's question, does the prediction actually help her patient?

"Understanding the AI decision process is critical for clinical adoption and enables pathologist-machine learning collaboration" (Nature Communications, 2025). Yet the models achieving the highest accuracy often operate as black boxes, learning patterns that remain opaque even to their creators. This post explores how the field is navigating the trade-off between performance and interpretability, what architectures show promise for having both, and why the validation gap between research and clinical deployment remains the central challenge.

The Performance Gap Is Real, But So Is the Validation Gap

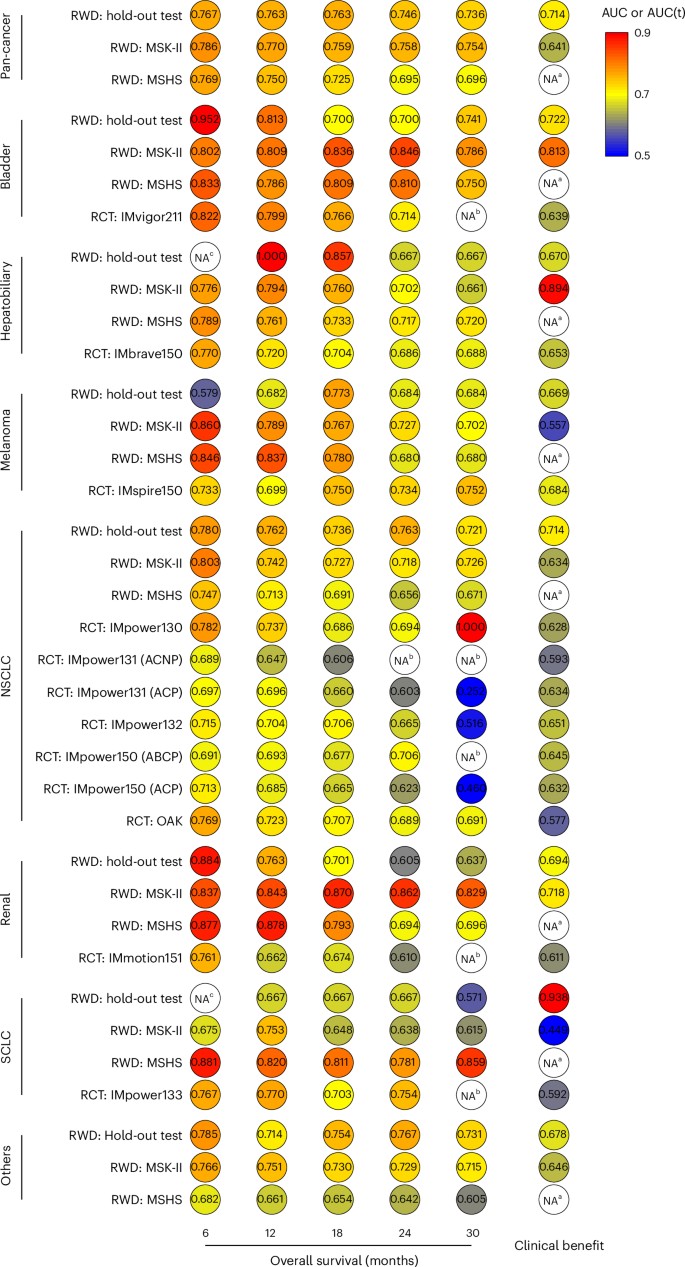

The numbers are striking. "Deep learning architectures, particularly autoencoders, graph neural networks, and transformers, outperform traditional methods by modeling complex nonlinear relationships across omics layers" (PMC12634751, 2025). These architectures achieve the kind of accuracy that matters clinically: "SCORPIO achieved median AUC 0.763 and 0.759 for predicting overall survival, substantially outperforming TMB (AUC 0.503-0.543)" (Nature Medicine, 2024).

Figure 1: SCORPIO machine learning model substantially outperforms FDA-approved biomarkers (TMB, PD-L1) for predicting checkpoint inhibitor response. The performance gap is clinically meaningful. Source: Nature Medicine, 2024

Figure 1: SCORPIO machine learning model substantially outperforms FDA-approved biomarkers (TMB, PD-L1) for predicting checkpoint inhibitor response. The performance gap is clinically meaningful. Source: Nature Medicine, 2024

But here is the uncomfortable truth that gets buried in research papers: "One model achieved AUC 0.92 but dropped to 0.68 in external validation, highlighting generalizability challenges" (PMC12634751, 2025). That 24-point drop represents the difference between a clinically useful tool and one that performs barely better than chance.

Why does this happen? "Ancestry-mediated gene expression differences and platform heterogeneity can degrade model performance by >30% across populations" (PMC12634751, 2025). A model trained predominantly on European ancestry populations may systematically fail when applied to other groups. Different sequencing platforms, library preparation protocols, and bioinformatics pipelines introduce batch effects that models learn to exploit rather than ignore.

"Algorithms perform well in controlled settings but fail in real-world heterogeneous populations" (BMC Cancer, 2025). This is not a solvable problem with more data alone. It requires rethinking how we build these models.

Why Clinicians Need to Understand Model Decisions

Consider this scenario from Memorial Sloan Kettering: their tumor-type classification model "changed diagnosis on 704 patients (0.88% of all profiled cases) during initial 8 months" (Penson et al., 2024). More significantly, "86.1% of diagnosis changes prompted changes in targeted therapy eligibility based on level 1 clinical evidence" (Cancer Discovery, 2024).

These are not abstract algorithmic outputs. These are treatment decisions affecting real patients.

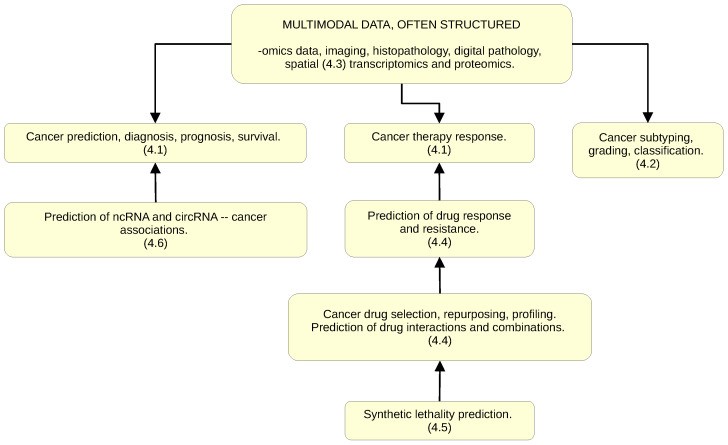

Figure 2: Six major application areas where Graph Neural Networks show promise in cancer research. GNNs' graph-based structure provides inherent interpretability advantages over traditional neural networks. Source: PMC10742144, 2024

Figure 2: Six major application areas where Graph Neural Networks show promise in cancer research. GNNs' graph-based structure provides inherent interpretability advantages over traditional neural networks. Source: PMC10742144, 2024

When the GDD-ENS model suggests changing a diagnosis that affects therapy selection, clinicians want to understand why. "Tumor-type classification enabled identification of genome-matched therapies in 47.8% (263/550) of patients with potentially targetable alterations, a 3.7-fold increase from 71 patients identified prior to classification" (Cancer Discovery, 2024). That 3.7-fold improvement matters, but it matters more when clinicians can verify the reasoning.

The interpretation challenge is particularly acute for variants of uncertain significance. "Over 98% of protein variants still have unknown consequences" (Frazer et al., 2021). When a model predicts a variant is pathogenic, clinicians want to know the reasoning behind that prediction, not just the probability score.

"Explainability is essential for deploying AI-derived biomarkers in clinical settings. Model transparency can minimize risks in AI-based decision-making in healthcare" (PMC10546466, 2024). The risks are concrete: a model could be relying on artifacts in the training data, learning spurious correlations, or encoding biases from unrepresentative populations.

The Black Box Problem in Genomic Prediction

Let me be specific about what makes genomic ML particularly challenging for interpretation. "The number of features or predictors is very large compared to the sample size" (PMC10558383, 2023). A typical targeted panel like MSK-IMPACT measures hundreds of genes. Whole-exome sequencing captures tens of thousands of variants. RNA-seq provides expression values for 20,000+ genes.

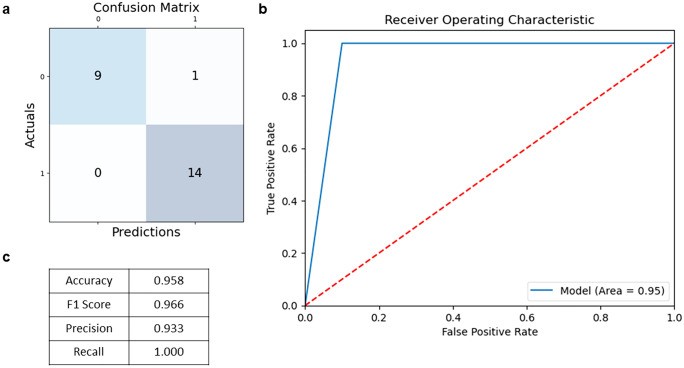

Figure 3: Standard ML evaluation metrics including ROC curves and confusion matrices. High performance on these metrics does not guarantee interpretable predictions or external validity. Source: PMC10558383, 2023

Figure 3: Standard ML evaluation metrics including ROC curves and confusion matrices. High performance on these metrics does not guarantee interpretable predictions or external validity. Source: PMC10558383, 2023

Traditional interpretable models struggle with this dimensionality. A comprehensive survey reviewing "over 100 papers published between 2008-2020" found that "almost half of the identified works used variants of the support vector machine (SVM) or tree-based algorithms, followed by linear models" (PMC8293929, 2021). These models are more interpretable than deep neural networks, but they often underperform on complex genomic tasks.

The deep learning models that achieve the best performance do so precisely because they capture complex nonlinear interactions that simpler models miss. But those interactions resist simple description. ML algorithms "can identify complex patterns in the data, which may not be replicated in independent validation datasets" (PMC10558383, 2023). When you have more features than samples, overfitting is the default outcome, not the exception.

Why Graphs Fit Biology: The GNN Architectural Thesis

Here is where the story gets interesting. Traditional machine learning treats genomic features as independent variables. A random forest does not know that BRCA1 and BRCA2 participate in the same DNA repair pathway. A logistic regression model cannot represent the fact that TP53 sits at the hub of cellular stress response networks. This independence assumption works surprisingly well for many problems, but it misses something about how cancer actually works.

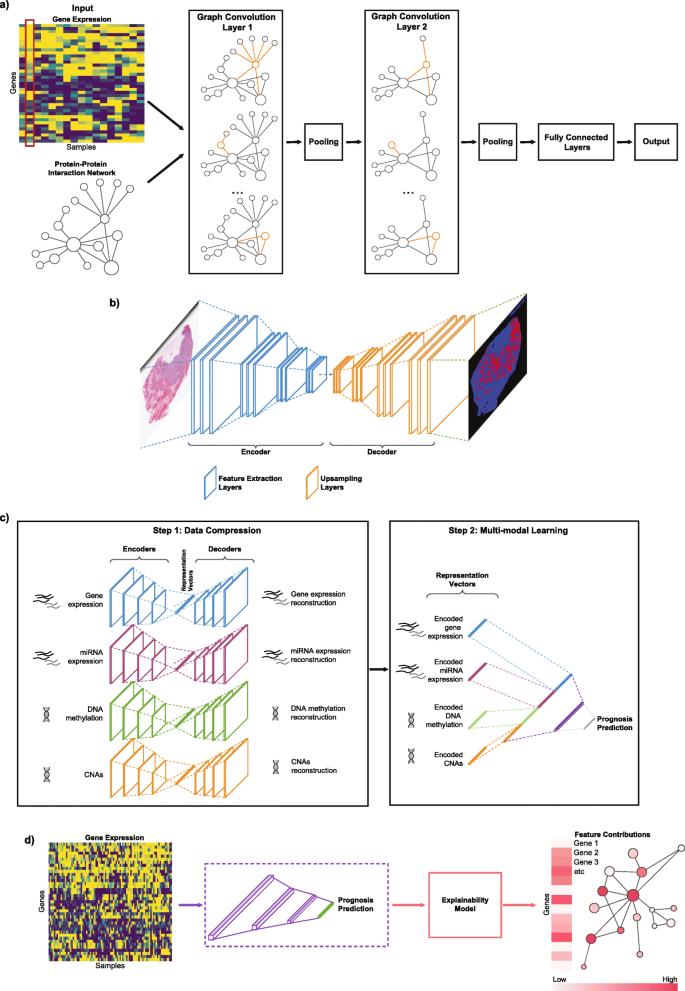

"Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) efficiently combine graph structure representations with the high predictive performance of deep learning, especially on large multimodal datasets. GNNs are indicated when data are naturally represented in graph structure form" (PMC10742144, 2024). And cancer biology is, at its core, a story of networks.

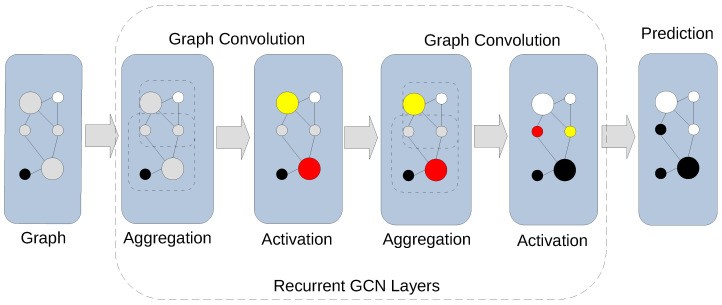

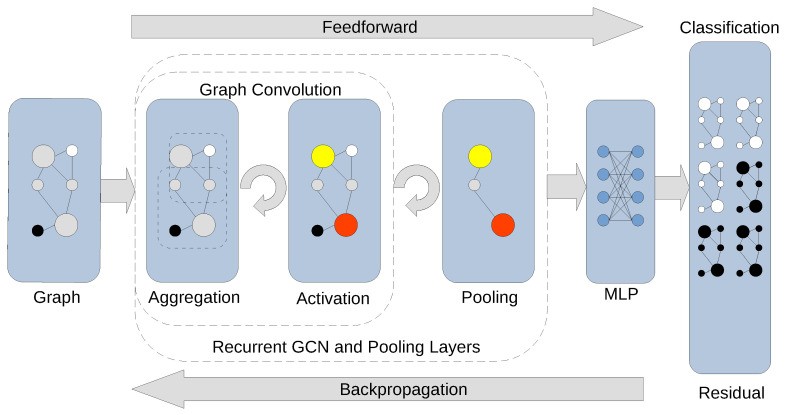

Figure 4: Graph convolution in a GCN showing aggregation and activation stages. The network learns by combining neighborhood features before applying non-linear activation. Source: PMC10742144, 2024

Figure 4: Graph convolution in a GCN showing aggregation and activation stages. The network learns by combining neighborhood features before applying non-linear activation. Source: PMC10742144, 2024

GNNs solve this by encoding biological relationships directly into the model architecture. When a GNN processes gene expression data, it does not just see expression values. It sees those values in context: which genes regulate which, which proteins interact, which pathways connect.

The mechanism is straightforward. Each node (gene, protein, or cell) aggregates information from its neighbors in the biological network. Then a non-linear transformation produces a new representation. Stack multiple layers, and you get increasingly sophisticated representations that capture multi-hop relationships. A mutation in EGFR affects downstream signaling partners, which affects transcription factors, which affects gene expression across the cell.

Figure 5: Convolutional layers stacked with pooling build progressively more abstract graph representations, enabling classification at the patient or tumor level. Source: PMC10742144, 2024

Figure 5: Convolutional layers stacked with pooling build progressively more abstract graph representations, enabling classification at the patient or tumor level. Source: PMC10742144, 2024

The advantage is significant. "CGMega outperforms current approaches in cancer gene prediction, and it provides a promising approach to integrate multi-omics information" (PMC10742144, 2024). When you encode biological prior knowledge into the model structure, you get better predictions and more interpretable results.

Geometric Deep Learning: When Network Topology Carries Information

One of the most innovative recent developments comes from geometric deep learning. Rather than treating the biological network as just a connectivity structure, researchers are extracting geometric features from the network topology itself.

"Geometric features obtained from the genomic network, such as Ollivier-Ricci curvature, enhance predictive capability while maintaining interpretability" (PMC10638676, 2023).

What does this mean practically? Ollivier-Ricci curvature measures how "curved" a region of the network is. Highly curved regions indicate dense clusters; negative curvature indicates sparse, bridge-like connections. These geometric properties carry biological meaning: dense clusters often represent functional modules, while bridge regions may indicate cross-talk between pathways.

A geometric GNN approach tested across 11 cancer types from TCGA and CoMMpass databases demonstrated "superior performance vs. Cox-EN, Cox-AE, alternative approaches" for survival prediction (PMC10638676, 2023). Importantly, the "identified potential biomarkers aligned with previous literature (e.g., WEE1, MCM in multiple myeloma)" (PMC10638676, 2023), providing biological validation that the model learned meaningful relationships.

This dual advantage (better prediction plus interpretable biology) addresses one of precision oncology's core challenges. "Clinical interpretation of genetic variants in the context of the patient's phenotype remains the largest component of cost and time expenditure" (Genome Medicine, 2021). Geometric GNNs offer a path toward automated interpretation that clinicians can actually trust.

Spatial Context: Where Position in the Tumor Matters

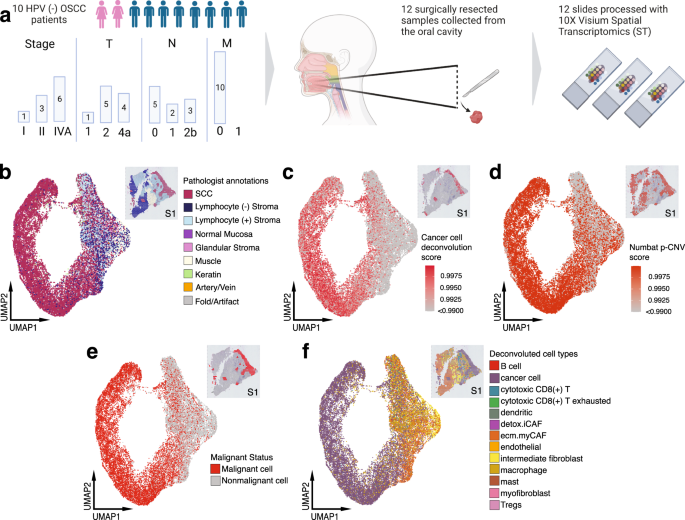

Spatial transcriptomics represents a fascinating case study in how richer biological data can improve both accuracy and interpretability. "Spatial transcriptomics technologies allow quantification and illustration of gene expression while preserving 2D positional information of cells" (Nature Communications, 2024).

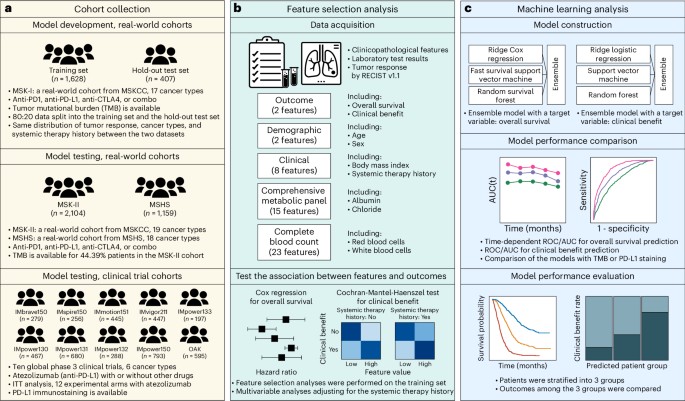

Figure 6: Spatial transcriptomics reveals distinct tumor architecture, with tumor core and leading edge showing different transcriptional profiles. This spatial context provides biologically interpretable predictions. Source: Nature Communications, 2023

Figure 6: Spatial transcriptomics reveals distinct tumor architecture, with tumor core and leading edge showing different transcriptional profiles. This spatial context provides biologically interpretable predictions. Source: Nature Communications, 2023

The clinical relevance is clear: "Tumor core and leading edge are characterized by unique transcriptional profiles. The LE gene signature is associated with worse clinical outcomes while TC gene signature is associated with improved prognosis across multiple cancer types" (Nature Communications, 2023).

Figure 7: Analysis showing leading edge gene signature predicts worse clinical outcomes across cancer types. Spatial signatures provide biologically meaningful, interpretable biomarkers. Source: Nature Communications, 2023

Figure 7: Analysis showing leading edge gene signature predicts worse clinical outcomes across cancer types. Spatial signatures provide biologically meaningful, interpretable biomarkers. Source: Nature Communications, 2023

This is interpretability through biological structure. When a model predicts poor prognosis based on a "leading edge signature," clinicians understand what this means: the tumor has an aggressive, invasive transcriptional profile at its boundary. The prediction maps onto biological intuition.

"Heterogeneous graph learning enables cell state identification from spatial data" and "identifies unique TME features like tertiary lymphoid structures" (Nature Communications, 2024). These are interpretable biological features: the model learns to recognize specific immune structures in the tumor microenvironment that predict response.

The Immunotherapy Prediction Challenge

Graph-based approaches shine particularly in predicting response to immune checkpoint inhibitors, one of precision oncology's most pressing challenges. "Only 20-30% of patients achieve durable responses to checkpoint inhibitors despite FDA approval" (Nature Medicine, 2024). "Current FDA-approved biomarkers (TMB and PD-L1) do not reliably predict response to immune checkpoint inhibitors across cancer types" (Nature Medicine, 2024).

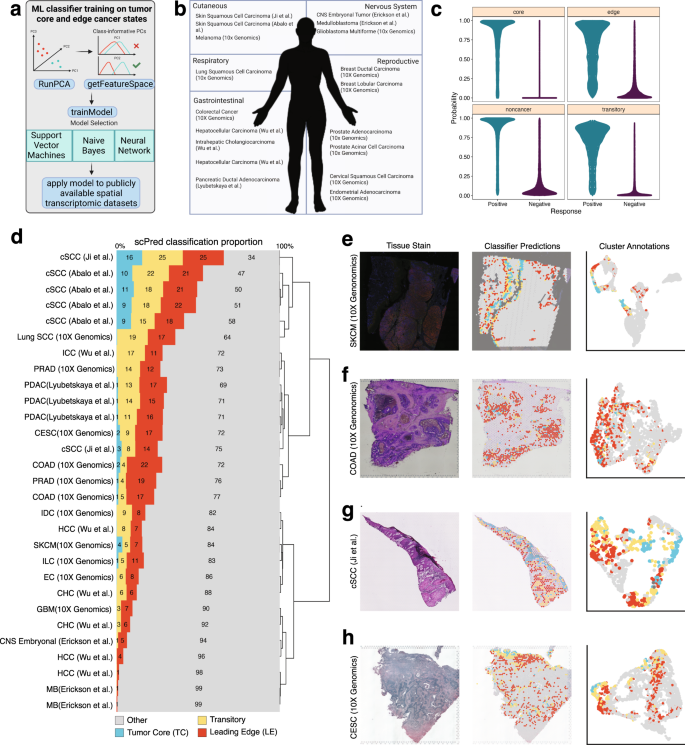

Figure 8: Overview of the SCORPIO model architecture for predicting checkpoint inhibitor immunotherapy response. The model's structure enables understanding of how clinical features contribute to predictions. Source: Nature Medicine, 2024

Figure 8: Overview of the SCORPIO model architecture for predicting checkpoint inhibitor immunotherapy response. The model's structure enables understanding of how clinical features contribute to predictions. Source: Nature Medicine, 2024

The SCORPIO model demonstrates what is possible when ML moves beyond single biomarkers. It was "trained on data from 1,628 patients across 17 cancer types from Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center" and "validated on data from 2 centers and 10 global phase 3 clinical trials," with a total dataset of 9,745 patients across 21 cancer types (Chowell et al., 2024).

What makes SCORPIO different from failed models? Three factors stand out:

Simple, accessible features. The "LORIS model uses just 5 clinical features (age, cancer type, prior therapy, albumin, NLR)" (Nature Medicine, 2024). "Model leverages routine blood tests and basic clinical data (age, albumin, neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio)" (Nature Medicine, 2024). Using readily available, standardized measurements reduces platform-dependent variation.

Multi-site training from the start. Training across multiple institutions forces the model to find generalizable patterns rather than institution-specific artifacts.

Extensive external validation. Testing on 10 global phase 3 trials provides evidence that performance holds across diverse populations and treatment contexts.

Biology-aware approaches go further. The NetBio framework "uses more than 700 ICI-treated patient samples with clinical outcomes and transcriptomic data" to build network-based biomarkers (2024). By "integrating gene pathways and protein interactions," it achieves "average concordance index of 0.59 +/- 0.13 across nine cancer types, compared to gold standard Cox-PH model (0.52 +/- 0.10)" (2024).

"Biology-aware mutation-based deep learning model integrates gene pathways and protein interactions" and "enables interpretable survival analysis for ICI-treated patients" (2024). When the model structure mirrors biological structure, predictions become more accurate and explanations become more meaningful.

Multi-Omics Integration: Where Complexity Meets Opportunity

The promise of multi-omics integration is substantial: "Combination of heterogeneous data types reveals biomarkers invisible to single modality analysis" (Nature Machine Intelligence, 2023). "Multimodal fusion substantially improves biomarker discovery compared to single-modality approaches" (Nature Machine Intelligence, 2023).

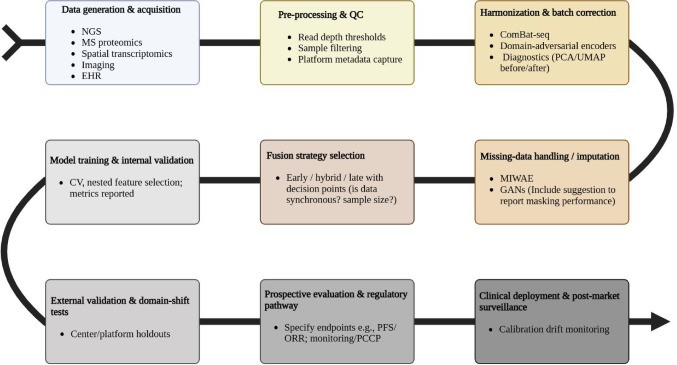

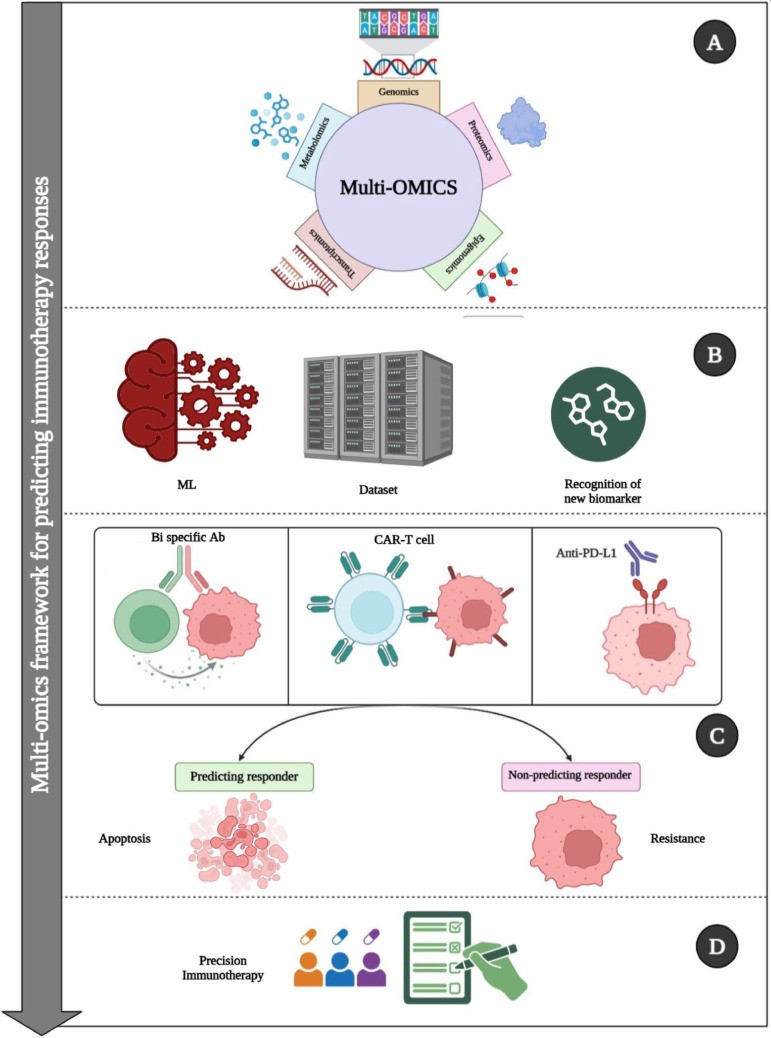

Figure 9: End-to-end AI-driven multi-omics workflow for precision oncology. Best practices include incorporating biological priors that enable interpretable predictions. Source: PMC12634751, 2025

Figure 9: End-to-end AI-driven multi-omics workflow for precision oncology. Best practices include incorporating biological priors that enable interpretable predictions. Source: PMC12634751, 2025

But integration compounds the validation problem. Data fusion strategies each carry trade-offs:

- "Early fusion combines features directly but risks amplifying technical noise" (PMC12634751, 2025)

- "Late fusion allows asynchronous data collection but misses cross-modal interactions" (PMC12634751, 2025)

- "Hybrid approaches using attention mechanisms dynamically weight each omics layer's relevance" (PMC12634751, 2025)

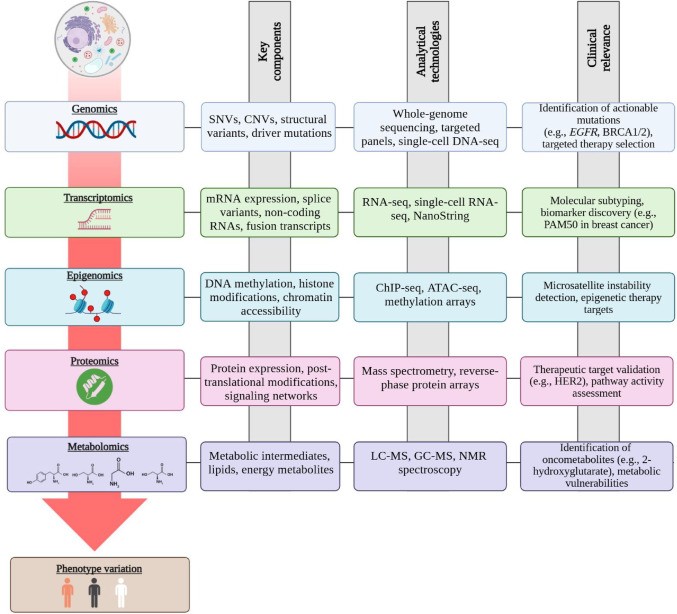

Figure 10: Multi-omics data layers including genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, and metabolomics. Integration promises better predictions but increases validation complexity. Source: PMC12634751, 2025

Figure 10: Multi-omics data layers including genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, and metabolomics. Integration promises better predictions but increases validation complexity. Source: PMC12634751, 2025

For challenging early detection tasks, "Integrated classifiers report AUCs around 0.81-0.87 for challenging early-detection tasks (e.g., pancreatic cancer)" (PMC12634751, 2025). For context, pancreatic cancer is notoriously difficult to detect early; current methods find it too late for most patients. An AUC of 0.87 represents clinically meaningful improvement. But these numbers come with significant validation requirements.

Why Simple Features Often Beat Complex Ones

A counterintuitive finding emerges from successful clinical models: simpler features often generalize better than complex ones.

"Performance rivals whole-genome sequencing-based methods despite using limited gene panel data" (Cancer Discovery, 2024). This matters because gene panels are standardized across institutions while whole-genome sequencing pipelines vary considerably.

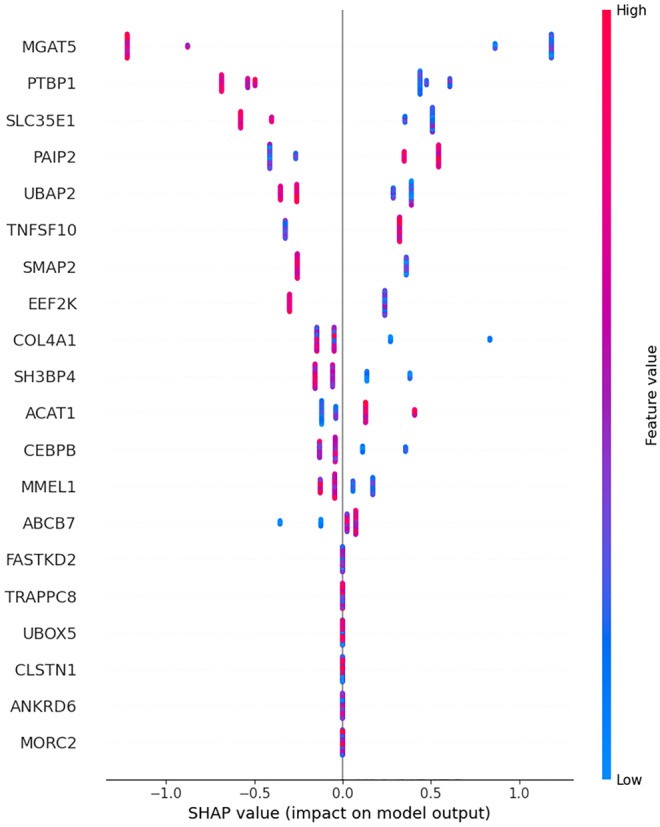

Figure 11: SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) summary plot showing feature importance for biomarker gene predictions. SHAP provides patient-level interpretability for black-box models. Source: PMC10558383, 2023

Figure 11: SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) summary plot showing feature importance for biomarker gene predictions. SHAP provides patient-level interpretability for black-box models. Source: PMC10558383, 2023

The GDD-ENS model demonstrates this principle. It "achieves 93% accuracy for high-confidence tumor-type predictions across 38 cancer types" using "limited gene panel data" that "works with existing clinical sequencing data (MSK-IMPACT panel)" (Cancer Discovery, 2024). "Model already incorporated into MSK-IMPACT clinical workflow for real-time deployment" (Cancer Discovery, 2024).

The clinical impact is substantial: 263 of 550 patients with targetable alterations were matched to therapies, compared to 71 before the model was deployed. This is not incremental improvement. Correctly classifying tumor origin can mean the difference between a targeted therapy with good response rates and a generic chemotherapy regimen.

The Explainability Infrastructure Gap

Despite these advances, the field faces an infrastructure gap. "Machine learning in precision oncology is in infant stages, with clinical integration still rare, despite remarkable developments in digital pathology and diagnostic radiology" (BMC Cancer, 2025).

"Post hoc XAI methods needed for complex neural networks" (PMC10546466, 2024). "Multiple XAI techniques available: LIME, SHAP, attention maps, Grad-CAM" (PMC10546466, 2024). The methods exist, but implementation is uneven. Many published models include detailed performance metrics but minimal interpretability analysis.

Figure 12: Different deep learning architectures (CNNs, RNNs, autoencoders) for cancer genomics applications. Architecture choice significantly affects interpretability potential. Source: Genome Medicine, 2021

Figure 12: Different deep learning architectures (CNNs, RNNs, autoencoders) for cancer genomics applications. Architecture choice significantly affects interpretability potential. Source: Genome Medicine, 2021

The problem extends beyond model development. "Comprehensive independent cross-benchmarking studies remain absent for most cancer applications" (PMC10742144, 2024). Without standardized benchmarks that include interpretability metrics, the field optimizes primarily for predictive accuracy.

"Technical challenges: missing data (30%+ in metabolomics), sparse proteomics signals, batch effects. Regulatory challenges: guidelines still emerging, professional guidance needed" (BMC Cancer, 2025).

Foundation Models and Transfer Learning

The emergence of foundation models presents both opportunities and challenges for interpretability. "Transfer learning from large public datasets (TCGA, GENIE) improves smaller dataset performance" (Nature Communications, 2025). Models pretrained on TCGA's "over 20,000 primary cancers and matched normal samples" spanning "33 cancer types" with "2.5+ petabytes of multi-omics data" can be fine-tuned for specific clinical applications (NCI).

The Threads foundation model, "pretrained on 47,171 H&E-stained tissue sections with paired genomic/transcriptomic data," demonstrates this approach. It "consistently shows state-of-the-art performance, covering four families of tasks: cancer subtyping, gene mutation prediction, immunohistochemistry status prediction, and treatment response prediction" (Nature, 2024).

"Cancer signatures transfer effectively between conditions. Pre-training on diverse cancer types improves rare cancer prediction" (PLOS ONE, 2020). "Foundation models enable rare cancer applications through transfer learning" (Nature Communications, 2025). For rare cancers where training data is limited, pretrained representations from larger datasets provide a foundation for interpretable models.

Federated Learning: Training Without Sharing Data

One solution to the validation gap: train on data from multiple institutions without requiring data sharing.

"The Oncology Federated Network trained models across 17 cancer centers while maintaining data sovereignty" (PMC12634751, 2025). "HARMONY+ consortium demonstrated federated learning maintaining model performance within 2% while preventing raw data egress" (PMC12634751, 2025).

Figure 13: Comprehensive workflow showing how AI integrates diverse multi-omics data to characterize tumor microenvironment for immunotherapy decisions. Federated approaches enable training across institutions without centralizing data. Source: PMC12634751, 2025

Figure 13: Comprehensive workflow showing how AI integrates diverse multi-omics data to characterize tumor microenvironment for immunotherapy decisions. Federated approaches enable training across institutions without centralizing data. Source: PMC12634751, 2025

The trade-off: "computational overhead significant (15-fold increase with homomorphic encryption)" (BMC Cancer, 2025). But for clinical deployment, this overhead may be acceptable if it enables models that actually generalize.

Practical Guidance: Building Interpretable Systems

For biomedical scientists developing ML systems for precision oncology, several principles emerge from this analysis.

Incorporate biological structure from the start. "GNNs are indicated when data are naturally represented in graph structure form" (PMC10742144, 2024). Genomic data has inherent structure: use it. Pathways, protein interactions, and regulatory networks provide interpretable scaffolding for model predictions.

Plan for interpretability, not just accuracy. When evaluating model architectures, consider explanation capability alongside predictive performance. "Hybrid approaches using attention mechanisms dynamically weight each omics layer's relevance" (PMC12634751, 2025) provide interpretability at modest computational cost.

Validate on diverse populations. "Ancestry-mediated gene expression differences and platform heterogeneity can degrade model performance by >30% across populations" (PMC12634751, 2025). Interpretability tools help diagnose whether failures reflect biological heterogeneity or dataset bias.

Use simpler models where appropriate. LORIS demonstrates that "just 5 clinical features" can predict immunotherapy response (Nature Medicine, 2024). Before building a complex deep learning pipeline, verify that simpler interpretable models are insufficient.

Train on multiple sites from the start. Do not develop on single-institution data with plans to validate later. The patterns you learn will be institution-specific. Multi-site training forces models to find generalizable patterns.

Document interpretation methods. "Guidelines still emerging, professional guidance needed" for clinical ML deployment (BMC Cancer, 2025). Until standards mature, explicit documentation of how predictions should be interpreted is essential.

What I Do Not Know

I have emphasized approaches where interpretability and performance coexist, but tensions remain. For some prediction tasks, the most accurate models resist interpretation despite best efforts. Whether this represents a limit or simply current technical limitations is unclear.

"Less than 5% of published studies incorporate multiple time points" (PMC12634751, 2025). Temporal dynamics in cancer progression may require models complex enough to resist simple interpretation. How to make longitudinal predictions interpretable remains an open problem.

Similarly, "Quantum computing promises 100-fold acceleration in variant screening and molecular simulations" (PMC12634751, 2025). If quantum ML becomes clinically relevant, new interpretability approaches will be needed.

I have also only validated these perspectives against the published literature. How these principles hold in practice at different institutions, with different data quality, and different clinical workflows is something I would genuinely like to know more about.

The Path Forward

The oncologist's question remains: "Why this patient?" The best answer comes not from post-hoc explanations of black-box predictions, but from models designed for interpretability from the start.

"Machine learning methods, molecular diagnostic workflows have an opportunity to integrate these tools to extract more information from next-generation sequencing data, enhance cancer variant interpretation, and generate therapeutic hypotheses for biomarker-negative patients" (Reardon et al., 2026). This opportunity is real, but realizing it requires models that clinicians can trust because they can understand.

"The era of individual analysis has passed and we are entering the era of data integration studies" (PMC8293929, 2021). Integration across omics layers, across institutions, and across patient populations will require sophisticated ML. The question is whether that sophistication will remain interpretable.

The models achieving clinical deployment share a characteristic: they provide not just predictions, but explanations that map onto biological and clinical reasoning. GDD-ENS explains tumor type predictions through genomic features clinicians recognize. SCORPIO uses clinical features oncologists already track. Spatial transcriptomics maps predictions onto visible tissue architecture.

This is the path forward: ML that speaks the language of biology and medicine, not just statistics. High-dimensional, nonlinear modeling power, channeled through architectures designed to explain themselves.

References

-

Chowell, D. et al. (2024). Prediction of checkpoint inhibitor immunotherapy efficacy for cancer using routine blood tests and clinical data. Nature Medicine. DOI: 10.1038/s41591-024-03398-5

-

Frazer, J. et al. (2021). Disease variant prediction with deep generative models of evolutionary data. Nature, 599, 91-95. DOI: 10.1038/s41586-021-04043-8 (Preprint: bioRxiv 2020, DOI: 10.1101/2020.12.21.423785)

-

National Cancer Institute. The Cancer Genome Atlas Program (TCGA). https://www.cancer.gov/ccg/research/genome-sequencing/tcga

-

Penson, A. et al. (2024). Deep-Learning Model for Tumor-Type Prediction Using Targeted Clinical Genomic Sequencing Data. Cancer Discovery, 14(6):1064-1076.

-

PMC. (2021). Machine learning analysis of TCGA cancer data. PeerJ Computer Science. PMC8293929.

-

PMC. (2023). The benefits and pitfalls of machine learning for biomarker discovery. PMC10558383.

-

PMC. (2023). Geometric graph neural networks on multi-omics data to predict cancer survival outcomes. PMC10638676.

-

PMC. (2024). Graph Neural Networks in Cancer and Oncology Research: Emerging and Future Trends. PMC10742144.

-

PMC. (2024). Interpretable artificial intelligence in radiology and radiation oncology. PMC10546466.

-

PMC. (2025). AI-driven multi-omics integration in precision oncology: bridging the data deluge to clinical decisions. PMC12634751.

-

Reardon, B., Culhane, A., Van Allen, E. (2026). Convergence of machine learning and genomics for precision oncology. Nature Reviews Cancer. DOI: 10.1038/s41568-025-00897-6

-

Shen, L. et al. (2024). Dissecting tumor microenvironment from spatially resolved transcriptomics data by heterogeneous graph learning. Nature Communications. DOI: 10.1038/s41467-024-49171-7

-

Wang, H. et al. (2023). Spatial transcriptomics reveals distinct and conserved tumor core and edge architectures. Nature Communications. DOI: 10.1038/s41467-023-40271-4

-

Wu, Z. et al. (2025). Pretrained Transformers Applied to Clinical Studies Improve Predictions of Treatment Efficacy and Associated Biomarkers. Nature Communications. DOI: 10.1038/s41467-025-57181-2

-

Xu, Y. et al. (2025). Realizing the promise of machine learning in precision oncology: expert perspectives on opportunities and challenges. BMC Cancer. DOI: 10.1186/s12885-025-13621-2

-

Transfer Learning with Convolutional Neural Networks for Cancer Survival Prediction (2020). PLOS ONE. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0230536

-

Threads Foundation Model (2024). A Slide-Level Foundation Model for Pathology. Nature.

-

Deep Learning in Cancer Diagnosis, Prognosis and Treatment Selection (2021). Genome Medicine. DOI: 10.1186/s13073-021-00968-x

-

Multimodal Data Fusion for Cancer Biomarker Discovery (2023). Nature Machine Intelligence. DOI: 10.1038/s42256-023-00633-5

-

Explainable Artificial Intelligence of DNA Methylation-Based Brain Tumor Diagnostics (2025). Nature Communications. DOI: 10.1038/s41467-025-57078-0