When Machines Design Their Own Learning Algorithms

A machine trained on simple grid worlds and toy problems recently beat every hand-designed reinforcement learning algorithm on Atari.1 Not by a small margin. It surpassed DQN, PPO, A3C, and other methods that took humans decades to develop. The algorithm that achieved this was not written by researchers. It was discovered by another algorithm.

A Nature 2025 paper from DeepMind demonstrates that machines can autonomously discover RL algorithms that outperform manually designed ones across challenging benchmarks. The discovered algorithm, called DiscoRL, generalized to environments it had never seen during training. This is not incremental improvement over existing methods. It represents something more interesting: the automation of algorithm design itself.

How did we get here? And what does it mean when the machines start designing their own learning rules?

Why Hand-Designed Algorithms Hit a Wall

Consider how traditional RL algorithms came to be. The original DQN paper describes "a convolutional neural network, trained with a variant of Q-learning, whose input is raw pixels and whose output is a value function estimating future rewards."2 Getting this to work required innovations like experience replay, which "randomly samples previous transitions, and thereby smooths the training distribution over many past behaviors."3 Each component emerged from human intuition about what makes neural network training stable.

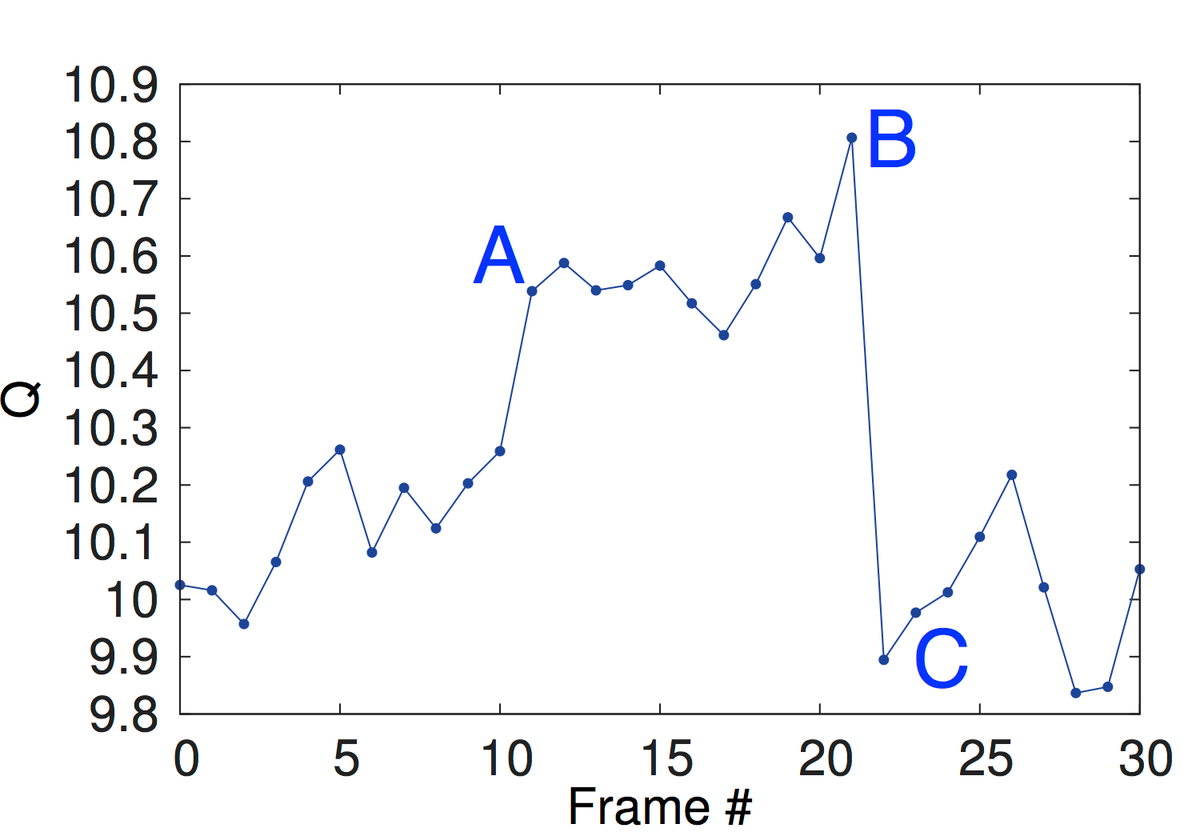

Q-value predictions during Atari gameplay: the network learns to anticipate future rewards before they occur. Source: Playing Atari with Deep Reinforcement Learning

Q-value predictions during Atari gameplay: the network learns to anticipate future rewards before they occur. Source: Playing Atari with Deep Reinforcement Learning

PPO followed a similar trajectory. Schulman and colleagues introduced "a new family of policy gradient methods for reinforcement learning, which alternate between sampling data through interaction with the environment, and optimizing a surrogate objective function using stochastic gradient ascent."4 The clipped objective that makes PPO work emerged from careful mathematical analysis and extensive experimentation.

But here is the uncomfortable truth: "The PPO code-optimizations are more important in terms of final reward achieved than the choice of general training algorithm (TRPO vs. PPO)."5 Research has shown that implementation details often matter as much as the algorithms themselves. This suggests the space of effective algorithms is richer than human designers have explored.

Hand-designed algorithms also encode assumptions that may not hold universally. The temporal difference update, the policy gradient theorem, the advantage function. Each represents one way to learn from experience. But are these the only ways? Are they the best ways?

Meta-Learning: Evolution for Algorithms

The key insight behind algorithm discovery is meta-learning: learning the learning process itself.

Think of it like biological evolution. Individual organisms learn within their lifetimes, adapting to their specific environments. Evolution operates at a higher level, discovering which learning mechanisms produce successful organisms across generations. Over millions of years, evolution has discovered learning algorithms far more sophisticated than anything humans have designed for computers.

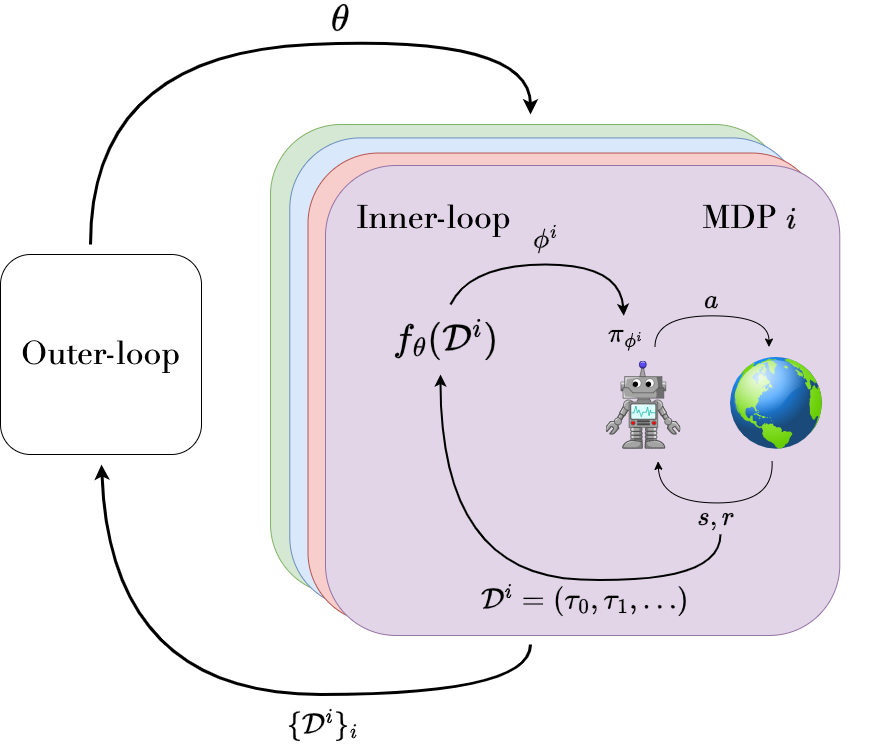

The meta-RL framework: an outer loop optimizes meta-parameters while the inner loop enables rapid task adaptation through environment interaction. Source: A Survey of Meta-Reinforcement Learning

The meta-RL framework: an outer loop optimizes meta-parameters while the inner loop enables rapid task adaptation through environment interaction. Source: A Survey of Meta-Reinforcement Learning

Algorithm discovery applies this same principle. The structure involves two nested optimization loops. The outer loop adjusts the parameters of the update rule itself. The inner loop applies that update rule to train agents on specific tasks. By evaluating how well agents perform after being trained with a given update rule, you can compute gradients that improve the update rule.

The original Learned Policy Gradient (LPG) paper introduced "a new meta-learning approach that discovers an entire update rule which includes both 'what to predict' (e.g. value functions) and 'how to learn from it' (e.g. bootstrapping) by interacting with a set of environments."1 Rather than fixing an objective like temporal difference error or policy gradient, you parameterize the entire learning procedure and optimize it across many tasks.

From Evolved Policy Gradients to DiscoRL

The idea of learning loss functions emerged from Evolved Policy Gradients (EPG), which "is a metalearning approach for learning gradient-based reinforcement learning (RL) algorithms. The core idea is to evolve a differentiable loss function, such that an agent, which optimizes its policy to minimize this loss, will achieve high rewards."6

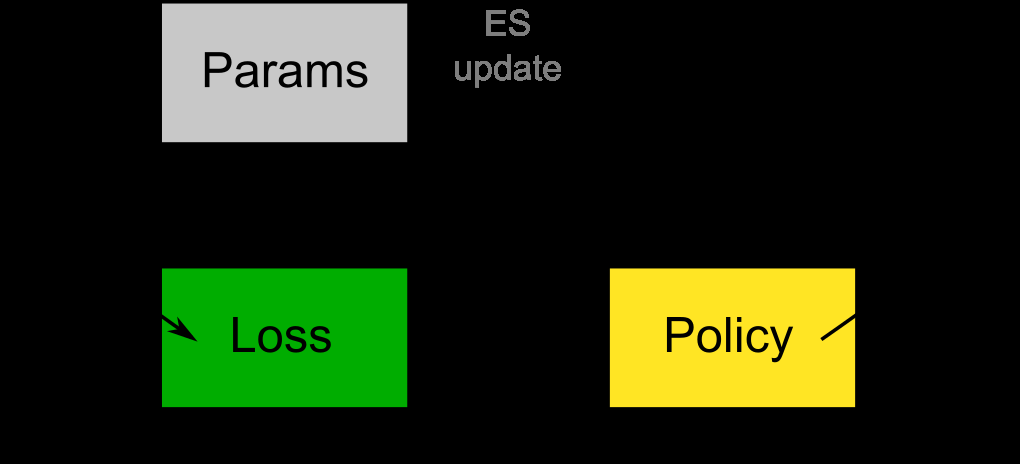

Evolved Policy Gradients: evolution searches over loss functions that train neural network policies through gradient descent. Source: Evolved Policy Gradients

Evolved Policy Gradients: evolution searches over loss functions that train neural network policies through gradient descent. Source: Evolved Policy Gradients

EPG uses evolution strategies for the outer loop. A population of loss functions is maintained, each evaluated by training agents from scratch and measuring their final performance. Loss functions that produce better agents are selected and mutated to create the next generation.

Why use evolution for the outer loop? "Due to the lack of easily exploitable structure in this optimization problem, we turn to evolution strategies (ES) as a black box optimizer."7 The fitness function is the final performance of agents trained with the evolved loss, which means you are directly optimizing for what matters.

The EPG loss network architecture: evolved temporal convolutions and dense layers process agent trajectories to produce loss signals for policy optimization. Source: Evolved Policy Gradients

The EPG loss network architecture: evolved temporal convolutions and dense layers process agent trajectories to produce loss signals for policy optimization. Source: Evolved Policy Gradients

The key is what gets evolved. Rather than a simple mathematical formula, EPG uses neural networks to represent loss functions. "The loss function consists of temporal convolutional layers which generate a context vector, and dense layers, which output the loss."8 This neural network takes in the agent's experience (states, actions, rewards) and outputs a scalar loss. The agent then backpropagates through this loss to update its policy.

LPG extended this approach. "LPG is a backward LSTM network that produces as output how to update the policy and the prediction vector."9 Rather than just learning a loss function, LPG learns the complete update rule, including what predictions to maintain (analogous to value functions) and how to use them. The architecture is "invariant to observation space and action space, as it does not take them as input."10 This generality proved essential for transfer.

DiscoRL builds on these ideas with significant improvements. The key innovation is meta-training across a diverse population of agents and environments simultaneously. The result surpassed all existing hand-designed methods on Atari and generalized to environments never seen during discovery.

What the Machines Discovered

The most surprising finding is that discovered algorithms independently reinvent concepts humans thought were necessary.

"Empirical results show that our method discovers its own alternative to the concept of value functions. Furthermore it discovers a bootstrapping mechanism to maintain and use its predictions."11

This is remarkable. The meta-learning process was not told to use value functions. It was not instructed to bootstrap predictions. These emerged because they are useful. "This result suggests that the proposed framework can automatically discover a rich and useful semantics of predictions that can almost recover the value functions at various horizons, even though such a semantics was not enforced during meta-training."12

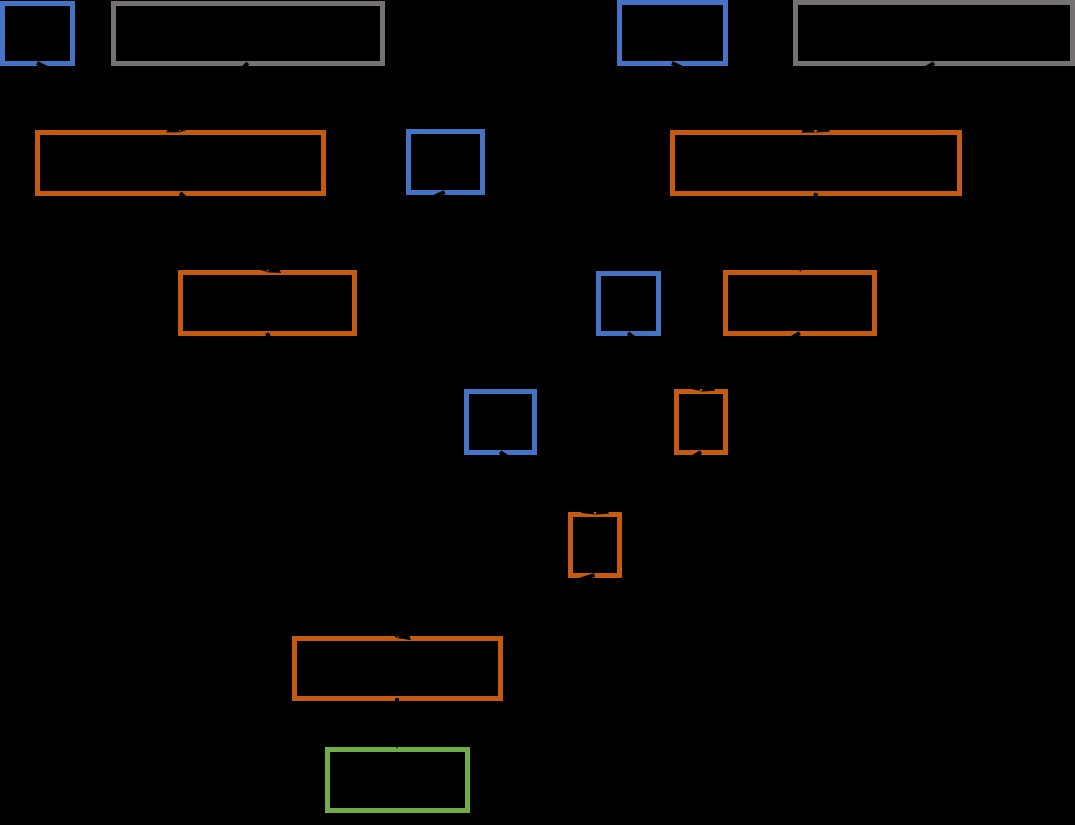

The algorithm discovery pipeline: RL update rules are represented as computational graphs and optimized through evolution across diverse training environments. Source: Evolving Reinforcement Learning Algorithms

The algorithm discovery pipeline: RL update rules are represented as computational graphs and optimized through evolution across diverse training environments. Source: Evolving Reinforcement Learning Algorithms

Parallel work on evolving RL algorithms through computational graph search achieved similar results. Starting from scratch on simple tasks, that research "rediscovers the temporal-difference (TD) algorithm."13 More importantly, it discovered "two new RL algorithms which outperform existing algorithms in both sample efficiency and final performance."14

The discovered algorithms also exhibit interesting specialization. "Although LPG is still behind the advanced RL algorithms such as A2C, the fact that LPG outperforms A2C on not just the training environments but also a few Atari games implies that LPG specialises in a particular type of RL problems instead of being strictly worse than A2C."15 Algorithm discovery may reveal a richer space of possible learning strategies than we currently understand.

Generalization: The Real Test

The value of discovered algorithms depends on whether they generalize beyond training environments. If you need to meta-train on every possible task, the approach offers little practical benefit.

The results here are encouraging. "Surprisingly, when trained solely on toy environments, LPG generalises effectively to complex Atari games and achieves non-trivial performance."16 Agents trained with discovered update rules achieved "super-human performance on 14 games, without relying on any hand-designed RL components such as value function but rather using its own update rule discovered from scratch."17

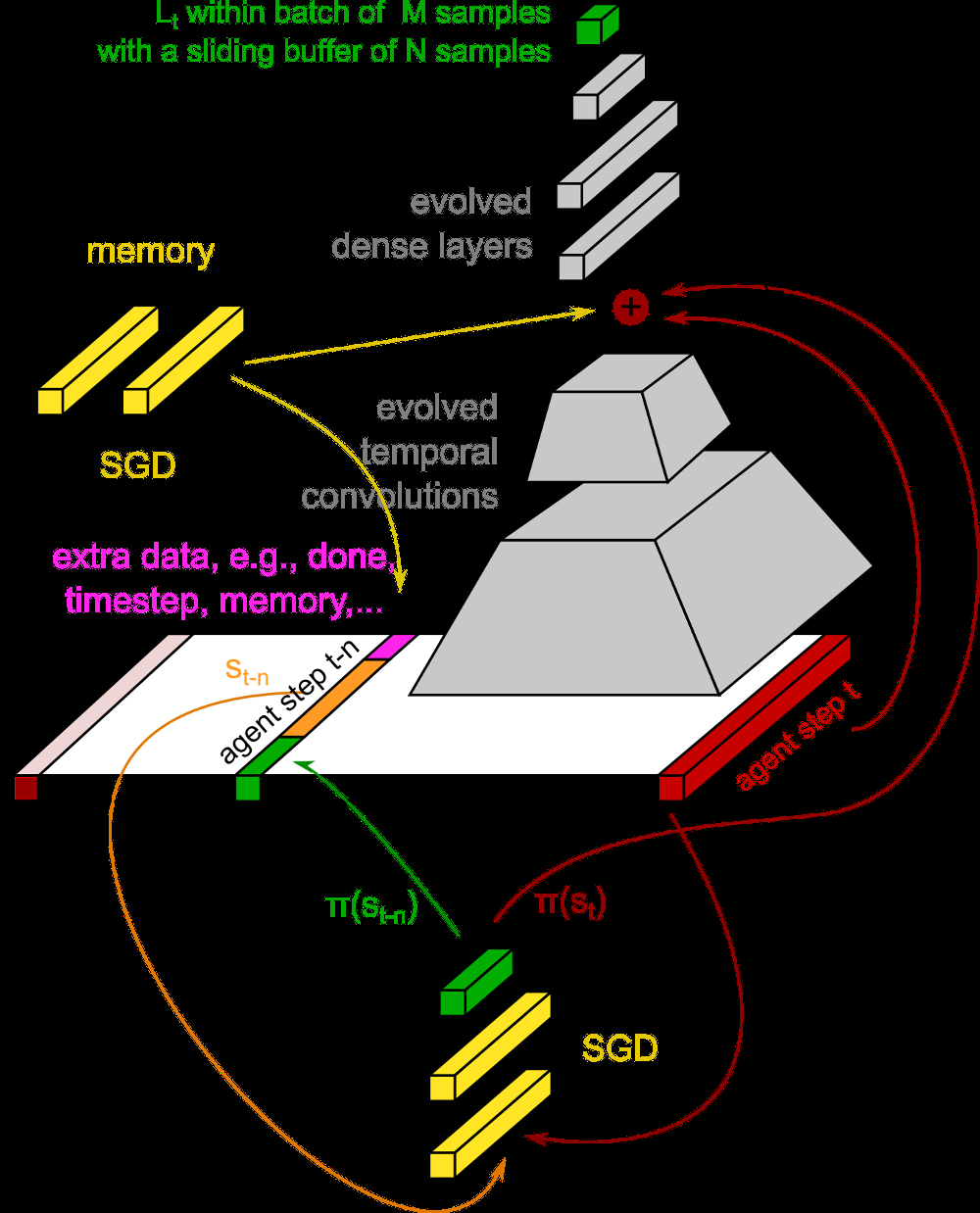

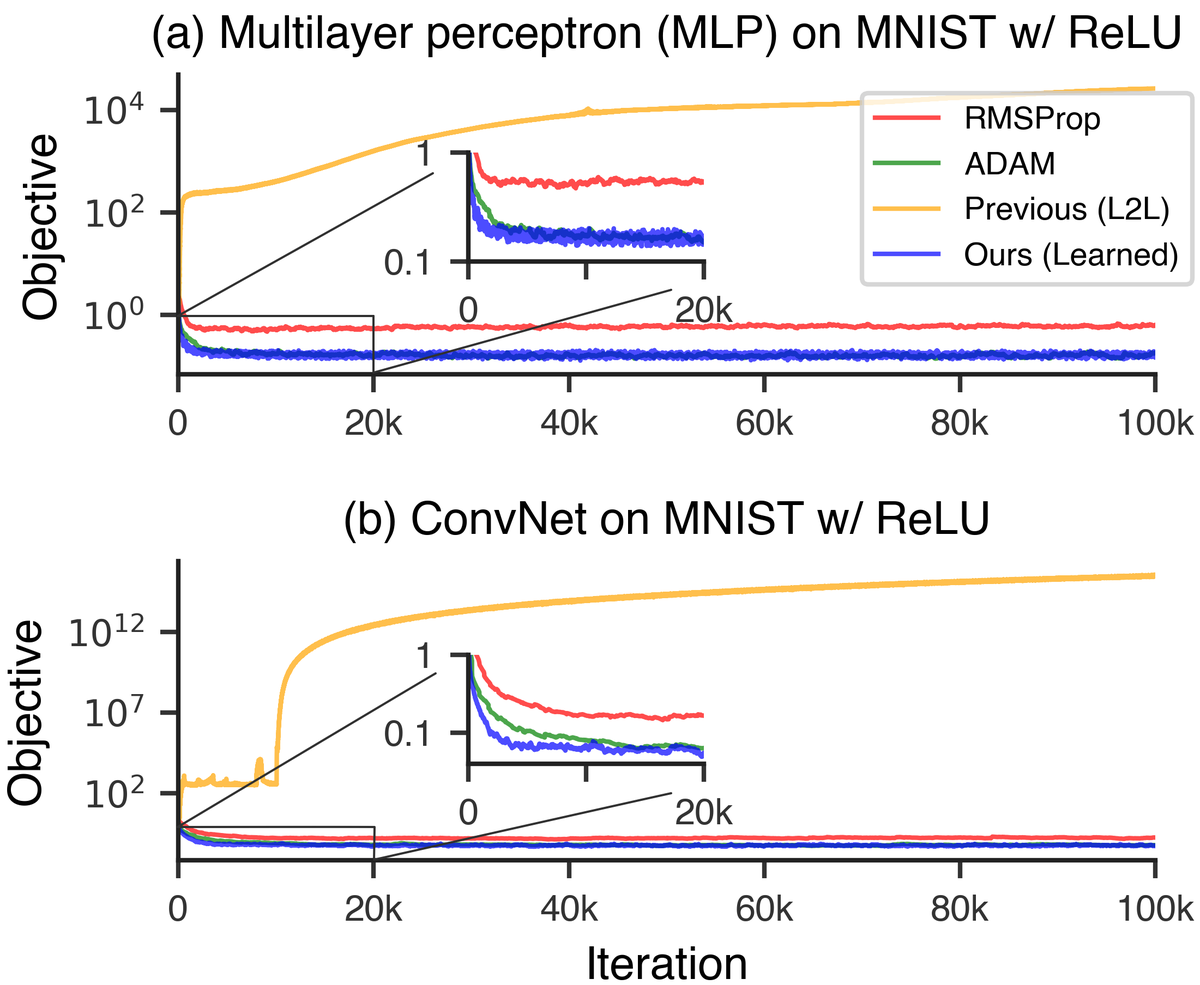

Learned optimizers significantly outperform hand-designed optimizers like ADAM and RMSProp, demonstrating the power of meta-learning optimization algorithms. Source: Learning to Learn by Gradient Descent by Gradient Descent

Learned optimizers significantly outperform hand-designed optimizers like ADAM and RMSProp, demonstrating the power of meta-learning optimization algorithms. Source: Learning to Learn by Gradient Descent by Gradient Descent

Related work on learned optimizers shows similar patterns. Learned optimizers "dramatically accelerate training of machine learning models" and can generalize to "train InceptionV3 and ResNetV2 architectures on the ImageNet dataset for thousands of steps, optimization problems that are of a vastly different scale than those it was trained on."18

The training environment design matters significantly. "We found that specific types of training environments, such as delayed chain MDPs, significantly improved the generalisation performance."19 Recent work on temporally-aware discovered algorithms shows that making the update rule aware of training horizon improves performance. These temporally-aware objectives "significantly improve upon the performance of their non-temporally-aware counterparts, improving generalization to previously unseen training horizons and environments."20

The scaling behavior is also promising. "The generalisation performance improves quickly as the number of training environments grows, which suggests that it may be feasible to discover a general-purpose RL algorithm once a larger set of environments are available for meta-training."21

Alternative Approaches: Symbolic Discovery

Neural network-based discovery is not the only path. Alternative approaches use evolutionary search over symbolic representations.

The search space for RL algorithms represented as a tree where branches encode different computational choices. Source: Evolving Reinforcement Learning Algorithms

The search space for RL algorithms represented as a tree where branches encode different computational choices. Source: Evolving Reinforcement Learning Algorithms

AutoML-Zero "demonstrates that it is possible today to automatically discover complete machine learning algorithms just using basic mathematical operations as building blocks."22 Rather than neural networks, it evolves programs composed of basic operations (addition, multiplication, conditionals). This produces interpretable algorithms that humans can analyze and understand.

The trade-offs between approaches are significant. Neural network-based discovery is more expressive and scales better, but produces black-box update rules. Symbolic evolution produces interpretable formulas but faces challenges scaling to complex algorithms. "We find that commonly used meta-gradient approaches fail to discover such adaptive objective functions while evolution strategies discover highly dynamic learning rules."23 Different methods excel at discovering different types of algorithms.

Practical Implications for AI Engineers

For practitioners, these results suggest several takeaways.

Algorithm discovery is becoming practical. The released DiscoRL code provides a starting point for applying discovered algorithms to new domains. As compute costs decrease and training environment design improves, custom algorithm discovery may become feasible for specific applications.

The choice of baseline algorithms matters less than we thought. If discovered algorithms can match or exceed hand-designed methods, the emphasis should shift toward building diverse training environments and running discovery rather than choosing between DQN, PPO, or A3C.

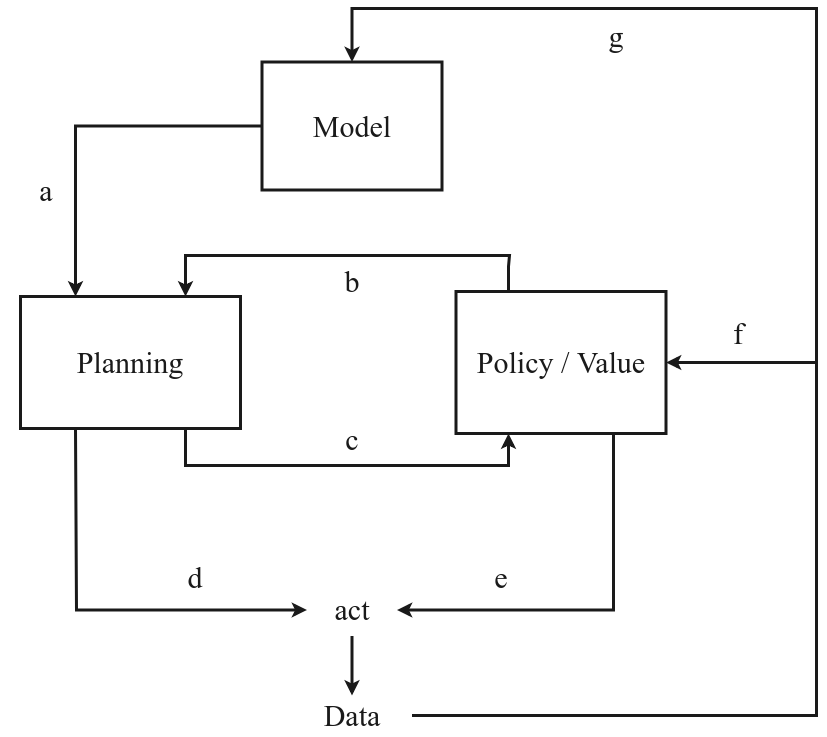

The model-based RL framework: learned models enable planning, which improves policy and value estimation. Source: Model-based Reinforcement Learning: A Survey

The model-based RL framework: learned models enable planning, which improves policy and value estimation. Source: Model-based Reinforcement Learning: A Survey

Model-based approaches complement these discoveries. Research on planning in model-based RL found that "planning is most useful in the learning process, both for policy updates and for providing a more useful data distribution."24 Combining discovered algorithms with learned world models remains an active area.

The research also "may serve as a tool to assist RL researchers in developing and improving their hand-designed algorithms."25 Discovered algorithms can reveal principles that humans then formalize and extend.

Limitations and Open Questions

Several challenges remain.

Computational cost is significant. Meta-training requires running thousands of inner-loop training runs across diverse environments. This is orders of magnitude more expensive than training a single agent with an existing algorithm. The resulting algorithm can then be applied efficiently, but the discovery process itself is expensive.

Interpretability is limited. While discovered algorithms can be analyzed to understand what they learn, they are substantially different from hand-designed methods that come with theoretical guarantees. "Despite lacking any theoretical convergence guarantees, our method is able to train large neural networks using a reinforcement learning signal and stochastic gradient descent in a stable manner."26 Stability is empirical, not proven.

Generalization boundaries are unclear. While DiscoRL generalizes impressively, we do not fully understand when discovered algorithms will transfer and when they will fail. The dependence on meta-training distribution creates potential for unexpected failures on out-of-distribution problems.

Looking Forward

The broader question is what else can be discovered. If RL update rules can be meta-learned, what about other components of AI systems? The success of learned optimizers suggests optimization algorithms are discoverable. Neural architecture search demonstrates that network structures can be found automatically.

The parallel to neural architecture search is instructive. NAS showed that machines could design better architectures than humans for specific tasks. But human researchers still define search spaces, evaluation metrics, and application domains. Algorithm discovery may follow a similar pattern: automated optimization within human-defined frameworks.

"The proposed approach has a potential to dramatically accelerate the process of discovering new reinforcement learning (RL) algorithms by automating the process of discovery in a data-driven way."27

We may be entering an era where the design of AI systems is itself automated. The machines are not just learning from data. They are learning how to learn. And sometimes, they design better learning algorithms than we do.

References

Footnotes

-

Oh, J., Hessel, M., Czarnecki, W. M., Xu, Z., van Hasselt, H., Singh, S., & Silver, D. (2020). Discovering Reinforcement Learning Algorithms. NeurIPS 2020 / arXiv:2007.08794. https://arxiv.org/abs/2007.08794 ↩ ↩2

-

Mnih, V., Kavukcuoglu, K., Silver, D., et al. (2013). Playing Atari with Deep Reinforcement Learning. arXiv:1312.5602. https://arxiv.org/abs/1312.5602 ↩

-

Mnih, V., et al. Experience replay innovation from DQN paper. arXiv:1312.5602. ↩

-

Schulman, J., Wolski, F., Dhariwal, P., Radford, A., & Klimov, O. (2017). Proximal Policy Optimization Algorithms. arXiv:1707.06347. https://arxiv.org/abs/1707.06347 ↩

-

Engstrom, L., Ilyas, A., Santurkar, S., Tsipras, D., Janoos, F., Rudolph, L., & Madry, A. (2020). Implementation Matters in Deep Policy Gradients: A Case Study on PPO and TRPO. arXiv:2005.12729. https://arxiv.org/abs/2005.12729 ↩

-

Houthooft, R., Chen, Y., Isola, P., Stadie, B., Wolski, F., Ho, J., & Abbeel, P. (2018). Evolved Policy Gradients. NeurIPS 2018 / arXiv:1802.04821. https://arxiv.org/abs/1802.04821 ↩

-

Houthooft, R., et al. Evolution strategies rationale. arXiv:1802.04821. ↩

-

Houthooft, R., et al. EPG loss architecture. arXiv:1802.04821. ↩

-

Oh, J., et al. LPG architecture. arXiv:2007.08794. ↩

-

Oh, J., et al. LPG invariance property. arXiv:2007.08794. ↩

-

Oh, J., et al. Value function discovery. arXiv:2007.08794. ↩

-

Oh, J., et al. Semantic discovery result. arXiv:2007.08794. ↩

-

Co-Reyes, J. D., Miao, Y., Peng, D., Real, E., Levine, S., Le, Q. V., Lee, H., & Faust, A. (2021). Evolving Reinforcement Learning Algorithms. ICLR 2021 / arXiv:2101.03958. https://arxiv.org/abs/2101.03958 ↩

-

Co-Reyes, J. D., et al. New algorithm performance. arXiv:2101.03958. ↩

-

Oh, J., et al. Specialization finding. arXiv:2007.08794. ↩

-

Oh, J., et al. Generalization to Atari. arXiv:2007.08794. ↩

-

Oh, J., et al. Superhuman performance result. arXiv:2007.08794. ↩

-

Wichrowska, O., Maheswaranathan, N., Hoffman, M. W., Gomez Colmenarejo, S., Denil, M., de Freitas, N., & Sohl-Dickstein, J. (2017). Learned Optimizers that Scale and Generalize. ICML 2017 / arXiv:1703.04813. https://arxiv.org/abs/1703.04813 ↩

-

Oh, J., et al. Training environment impact. arXiv:2007.08794. ↩

-

Jackson, M. T., Lu, C., Kirsch, L., Lange, R. T., Whiteson, S., & Foerster, J. N. (2024). Discovering Temporally-Aware Reinforcement Learning Algorithms. ICLR 2024 / arXiv:2402.05828. https://arxiv.org/abs/2402.05828 ↩

-

Oh, J., et al. Scaling behavior. arXiv:2007.08794. ↩

-

Real, E., Liang, C., So, D. R., & Le, Q. V. (2020). AutoML-Zero: Evolving Machine Learning Algorithms From Scratch. ICML 2020 / arXiv:2003.03384. https://arxiv.org/abs/2003.03384 ↩

-

Jackson, M. T., Lu, C., Kirsch, L., Lange, R. T., Whiteson, S., & Foerster, J. N. (2024). Discovering Temporally-Aware Reinforcement Learning Algorithms. ICLR 2024 / arXiv:2402.05828. https://arxiv.org/abs/2402.05828 ↩

-

Moerland, T. M., Broekens, J., Jonsson, A., & Plaat, A. (2020). Model-based Reinforcement Learning: A Survey. arXiv:2006.16712. https://arxiv.org/abs/2006.16712 ↩

-

Oh, J., et al. Research tool potential. arXiv:2007.08794. ↩

-

Mnih, V., et al. Stability finding. arXiv:1312.5602. ↩

-

Oh, J., et al. Discovery acceleration potential. arXiv:2007.08794. ↩