The Stability-Plasticity Dilemma: How Memory Architectures Are Solving Continual Learning

You train a language model on financial data. It learns to predict stock movements, interpret earnings reports, analyze market sentiment. Then you fine-tune it on medical literature. It becomes adept at clinical reasoning, drug interactions, diagnostic patterns.

And suddenly, it has no idea what an earnings call is.

This is catastrophic forgetting, and it represents one of the most persistent challenges facing anyone deploying language models in production. The problem traces back to studies in the 1980s and 1990s, but it has become urgent now that foundation models represent millions of dollars in compute investment. You cannot simply retrain from scratch every time new data arrives.

Recent research quantifies just how severe this problem is. Full fine-tuning on new knowledge can cause "89% drops in F1 scores" on previously learned tasks (Lin et al., 2025). Even parameter-efficient methods like LoRA, which update only a small fraction of weights, still show 71% forgetting rates in some settings. These are not edge cases; this is the default behavior of neural networks under sequential training.

But here is what makes this moment interesting: a new class of approaches built around sparse memory layers can reduce forgetting to just 11%, while still acquiring new knowledge effectively. This represents a genuine step change in how we might build systems that learn continuously.

I want to develop a specific thesis in this post: the most promising solutions treat continual learning not as a regularization problem but as a memory architecture problem. By changing where and how models store knowledge, rather than constraining how they update parameters, recent work achieves forgetting rates that would have seemed impossible five years ago.

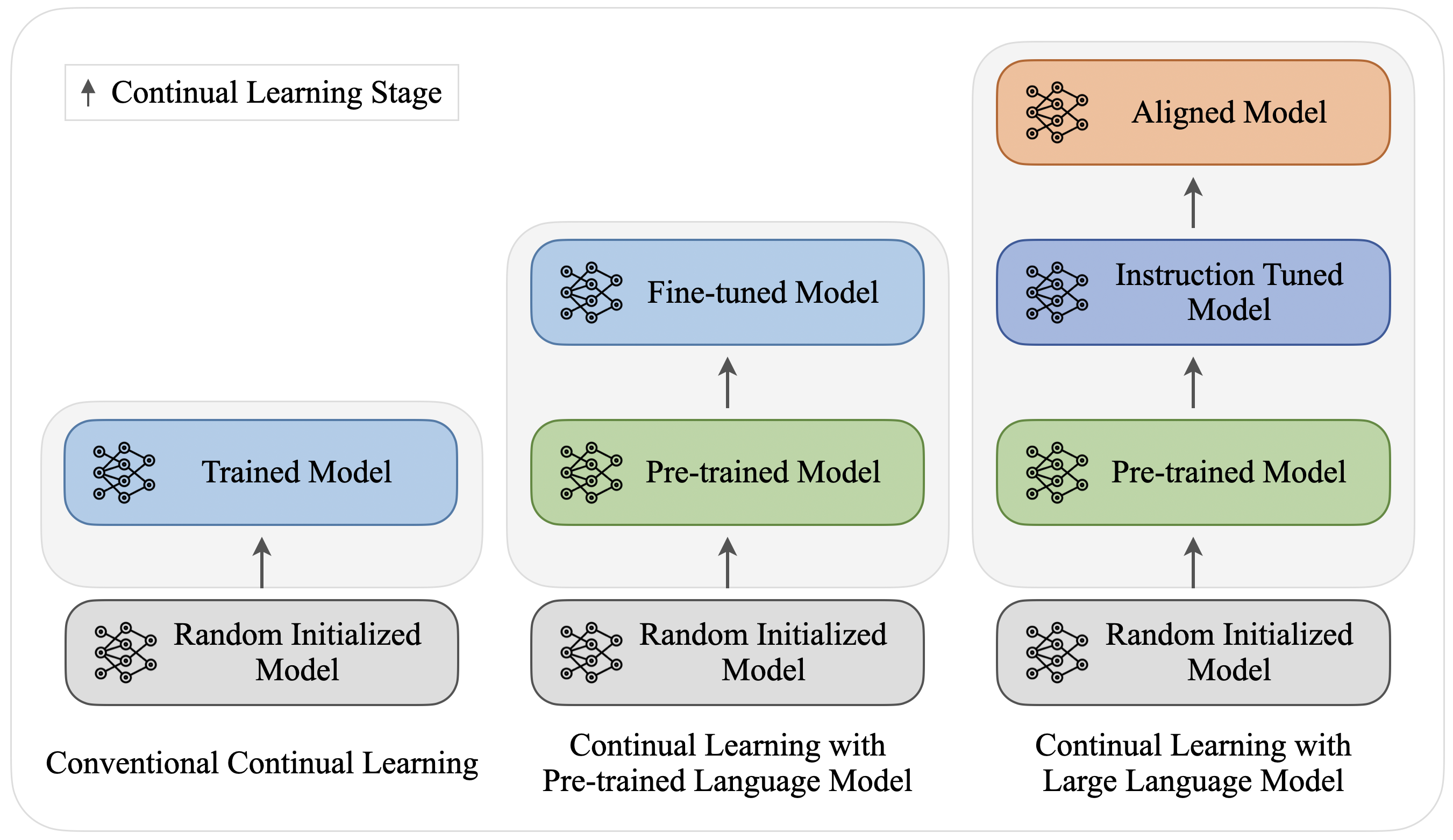

Figure 1: The evolution of continual learning approaches, from conventional methods with random initialization to modern LLM-based systems with pre-trained foundations. Source: Wu et al., 2024

Figure 1: The evolution of continual learning approaches, from conventional methods with random initialization to modern LLM-based systems with pre-trained foundations. Source: Wu et al., 2024

Why Standard Training Fails

Before examining solutions, we need to understand why the naive approach fails so dramatically.

Standard neural network training optimizes parameters to minimize loss on the current training distribution. When you fine-tune on a new task, the optimizer has no mechanism to preserve performance on previous tasks. It simply overwrites whatever parameters are most useful for the new objective. The result is predictable: accuracy on old tasks plummets.

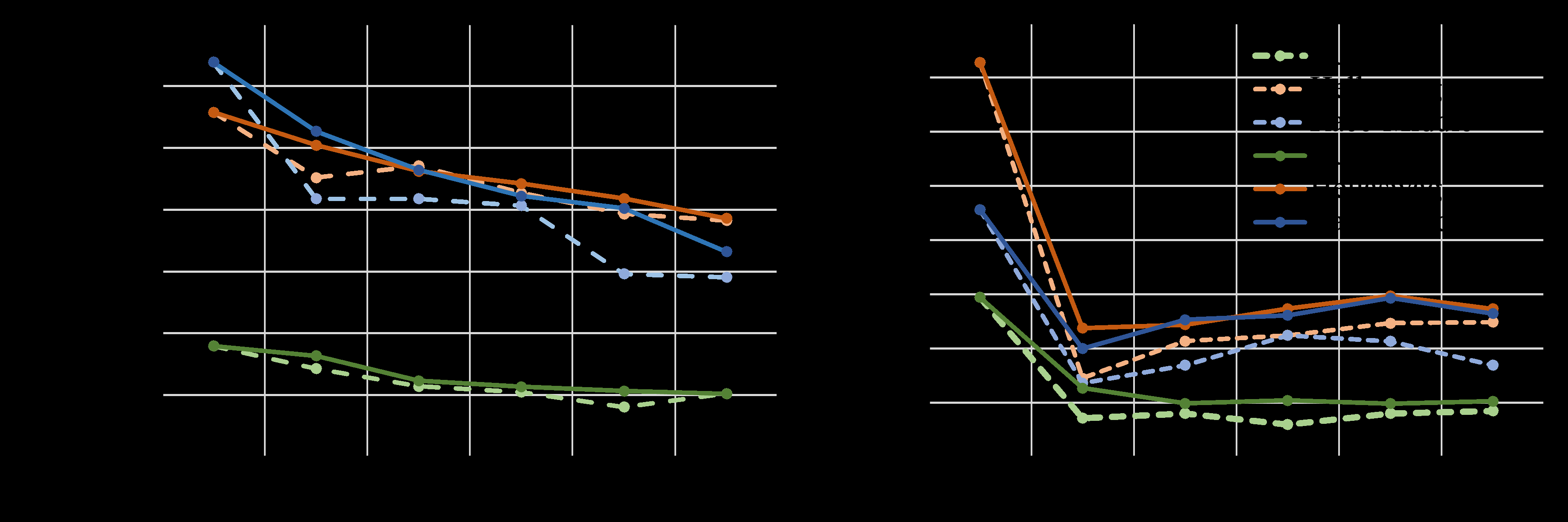

Here is a counterintuitive finding that challenges assumptions about bigger models being more robust: "catastrophic forgetting is generally observed in LLMs ranging from 1B to 7B parameters," and "as model scale increases, the severity of forgetting intensifies" within this range (Luo et al., 2023). Larger models, at least in this range, actually forget more. They had more capacity and thus more performance to lose.

Figure 2: Performance degradation across continual learning methods, showing how different approaches mitigate the forgetting problem. Source: Luo et al., 2023

Figure 2: Performance degradation across continual learning methods, showing how different approaches mitigate the forgetting problem. Source: Luo et al., 2023

This finding matters because the intuition that scale solves everything is common in ML. For catastrophic forgetting, scale alone does not save you. You need architectural or algorithmic solutions.

At its heart, continual learning forces a fundamental trade-off that researchers call the stability-plasticity dilemma. A model needs plasticity to learn new information. But it also needs stability to retain old knowledge. These two requirements pull in opposite directions. If you make weights resistant to change, the model struggles to learn anything new. If you let weights change freely, old knowledge gets overwritten.

The research literature identifies "three main strategies for continual learning: replay-based, regularization-based, and parameter isolation" (Wu et al., 2024). Each makes different assumptions about how to resolve this dilemma. A fourth category, memory augmentation, combines aspects of parameter isolation with efficient parameter sharing.

Parameter Regularization: Protecting Important Weights

The first major approach emerged from a simple intuition: if some weights are more important than others for a task, we should protect them during subsequent training.

Elastic Weight Consolidation (EWC), introduced by Kirkpatrick et al. in 2017, operationalizes this idea using the Fisher information matrix. EWC "prevents important weights from deviating far from consolidated values during learning" (Chaudhry et al., 2021). Weights that significantly affect the loss for task A should change slowly when learning task B. The approach adds a quadratic penalty term that slows down learning on weights important for previously learned tasks while still allowing updates to less critical parameters.

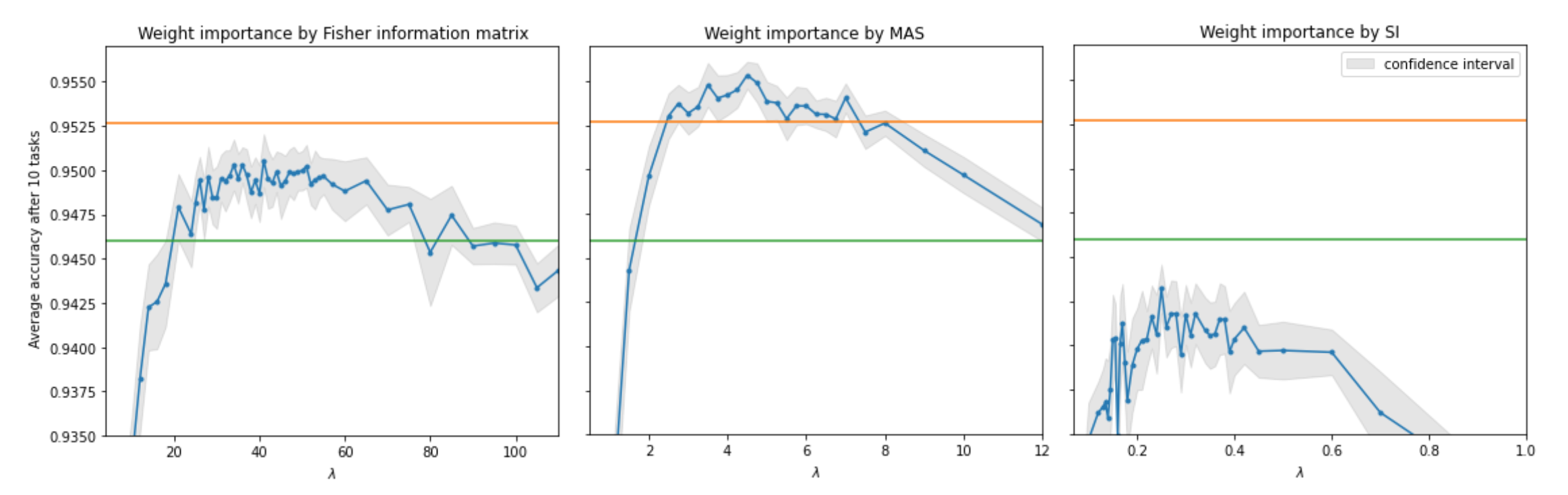

Figure 3: The effect of regularization strength (lambda) on continual learning accuracy across different weight importance methods, including Fisher, MAS, and Synaptic Intelligence. Source: Chaudhry et al., 2021

Figure 3: The effect of regularization strength (lambda) on continual learning accuracy across different weight importance methods, including Fisher, MAS, and Synaptic Intelligence. Source: Chaudhry et al., 2021

The approach works, to a point. Studies show that "the gain from using EWC was about 7 units of perplexity" compared to conventional fine-tuning (Chaudhry et al., 2021). Extensions like Memory Aware Synapses (MAS) achieve "0.9553 average accuracy outperforming Fisher-based importance at 0.9505" on benchmark tasks (Chaudhry et al., 2021). EVCL, which combines variational methods with EWC, reaches "93.5% on Permuted MNIST significantly outperforming VCL at 91.5%" and "98.4% on Split MNIST compared to VCL at 94%" (Asai et al., 2024).

But parameter regularization has fundamental limitations. The approach assumes importance can be accurately estimated after each task. It assumes different tasks use largely disjoint parameter subsets. And it struggles with long task sequences: as more parameters become "important," less capacity remains for new learning.

The gradient explosion problem presents practical challenges too. Original EWC formulations "experience gradient explosion when applied to deep networks with convolutional and self-attention layers" (Chaudhry et al., 2021). While stabilization techniques exist, they add complexity.

When to use regularization approaches: When you have moderate compute constraints, a small number of sequential tasks (fewer than 10), and can accept some forgetting in exchange for simplicity. These methods add minimal architectural complexity and work with any existing model.

Parameter Isolation: Dedicated Networks per Task

A more radical approach: don't try to share parameters at all. Instead, dedicate separate network subsets to each task.

Progressive Neural Networks take this to its logical extreme. Old task weights remain "frozen while new task columns with lateral connections leverage previously learned features" (Rusu et al., 2016). The result is zero forgetting, guaranteed by construction. You simply cannot overwrite weights that never update.

Figure 4: A 3D navigation environment used for evaluating progressive networks on transfer learning tasks. The approach demonstrates strong knowledge transfer via lateral connections. Source: Rusu et al., 2016

Figure 4: A 3D navigation environment used for evaluating progressive networks on transfer learning tasks. The approach demonstrates strong knowledge transfer via lateral connections. Source: Rusu et al., 2016

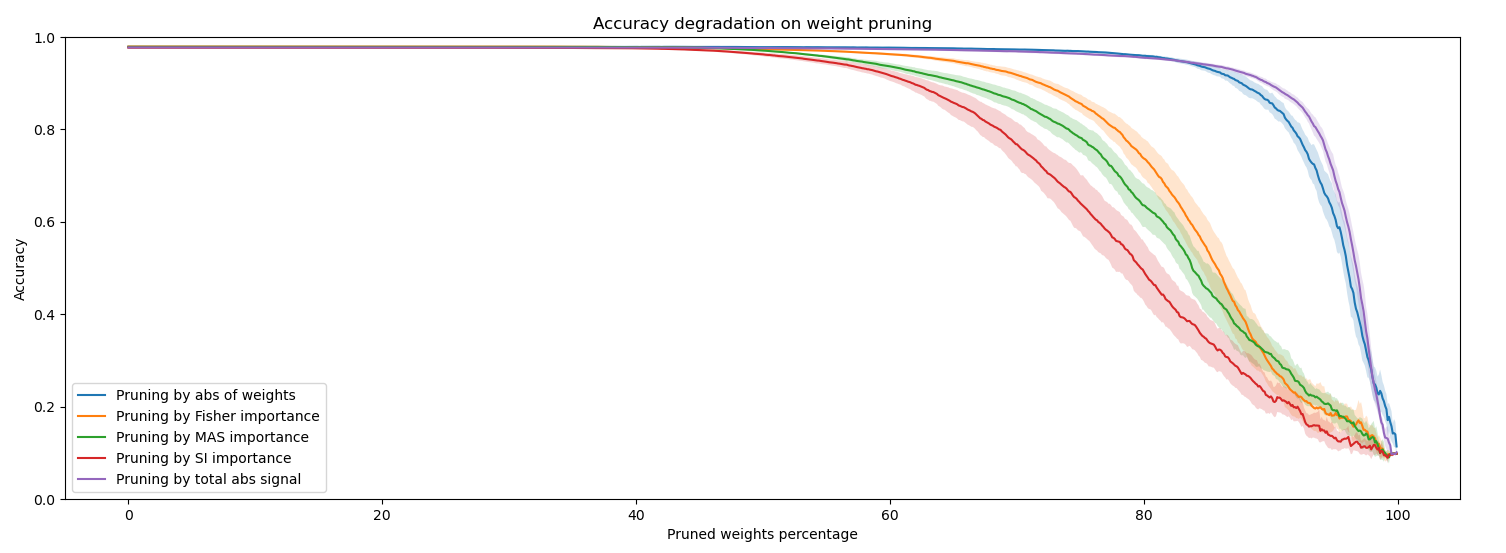

PackNet offers a more parameter-efficient variant. Rather than adding new columns, it "exploits redundancies in large deep networks to free up parameters that can be employed to learn new tasks" (Mallya & Lazebnik, 2017). Through iterative pruning, PackNet carves task-specific subnetworks from a single model. The insight: modern neural networks are massively overparameterized. You can often achieve near-identical performance with a fraction of the parameters.

Figure 5: Network accuracy degradation under different weight pruning strategies, illustrating how different importance measures affect model robustness. Source: Chaudhry et al., 2021

Figure 5: Network accuracy degradation under different weight pruning strategies, illustrating how different importance measures affect model robustness. Source: Chaudhry et al., 2021

The appeal of isolation approaches is their theoretical cleanliness. No complex regularization terms. No forgetting-learning trade-offs. Tasks simply don't interfere because they don't share parameters.

The cost is model complexity. Progressive Networks grow linearly with task count. After learning 100 tasks, you have 100 columns. PackNet eventually exhausts available parameters. Neither approach scales gracefully to the hundreds or thousands of tasks that production systems might encounter.

When to use parameter isolation: When forgetting is absolutely unacceptable, you have relatively few tasks (fewer than 20), and either model size growth (Progressive Networks) or available capacity (PackNet) is not a binding constraint.

Memory-Augmented Architectures: The Architecture Solution

The most recent and most promising direction treats continual learning as an architecture problem rather than a training problem. If forgetting happens because the same parameters must serve multiple purposes, the solution is to give the model more parameters, specifically, the right kind of parameters.

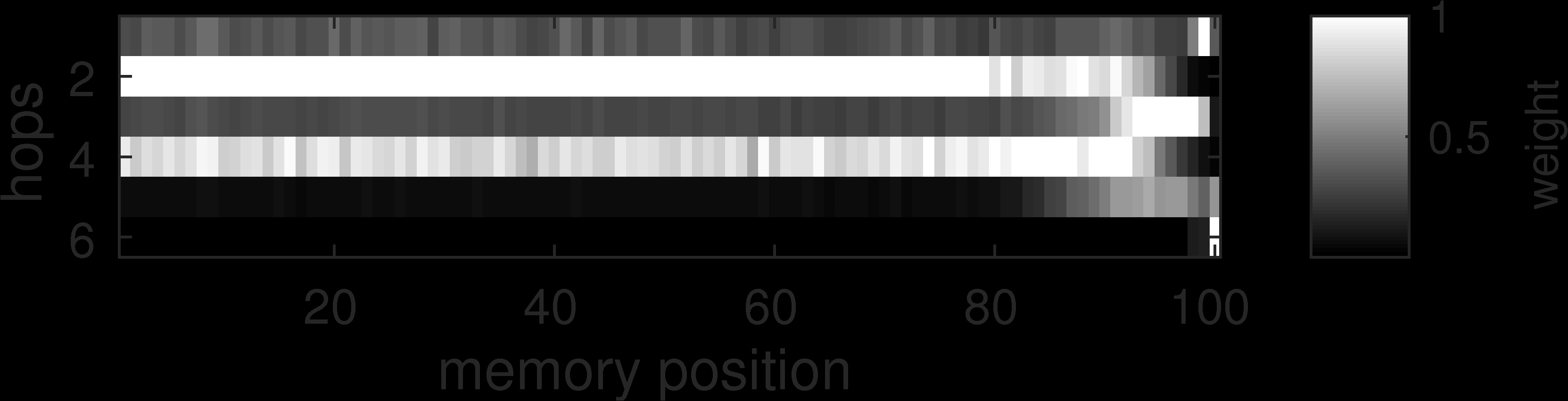

Memory-augmented neural networks have a long history. Neural Turing Machines (2014) introduced "a differentiable external memory interacting with a neural controller via attention mechanisms" (Graves et al., 2014). Memory Networks (2015) demonstrated that "multiple computational hops over memory yield improved results" for question-answering, achieving "111 test perplexity on Penn Treebank vs 115 for RNN/LSTM baselines" (Weston et al., 2015).

Figure 6: Memory network attention patterns across reasoning hops, showing how the network learns to focus on relevant memory slots during multi-step inference. Source: Weston et al., 2015

Figure 6: Memory network attention patterns across reasoning hops, showing how the network learns to focus on relevant memory slots during multi-step inference. Source: Weston et al., 2015

When I first encountered memory-augmented approaches, I was skeptical. They seemed like a heavy-handed solution to a training problem. But the sparse activation insight changed my perspective entirely.

Modern memory layer architectures adapt these foundational ideas for large language models. The key innovation is sparse activation: rather than updating all parameters during learning, memory layers activate only a small subset of memory slots for each input. This natural sparsity creates the conditions for continual learning almost automatically.

Figure 7: Neural Turing Machine memory access patterns showing read/write head positions during computation. This foundational architecture established the principles now used in modern memory layers. Source: Graves et al., 2014

Figure 7: Neural Turing Machine memory access patterns showing read/write head positions during computation. This foundational architecture established the principles now used in modern memory layers. Source: Graves et al., 2014

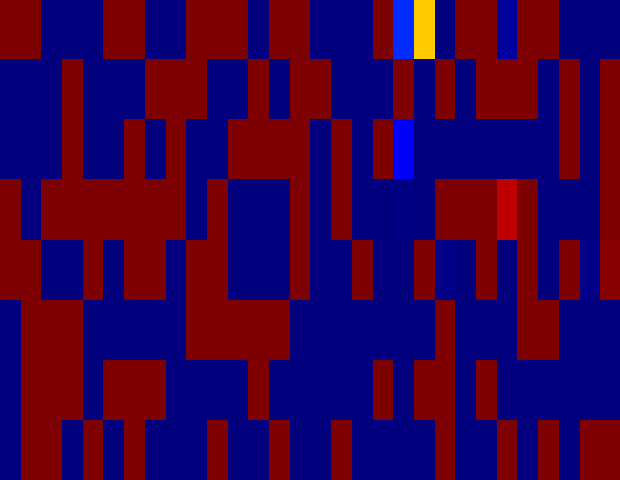

The PEER architecture demonstrates the efficiency gains possible with modern memory designs. It uses "routing mechanisms to direct inputs to specialized expert modules" and "reduces catastrophic forgetting by 45% compared to standard fine-tuning" (He et al., 2024).

Figure 8: Perplexity vs parameter count for different architectures. PEER achieves better perplexity with fewer active parameters than dense models and traditional MoE approaches. Source: He et al., 2024

Figure 8: Perplexity vs parameter count for different architectures. PEER achieves better perplexity with fewer active parameters than dense models and traditional MoE approaches. Source: He et al., 2024

But the breakthrough results come from sparse memory finetuning. By "updating only the memory slots that are highly activated by a new piece of knowledge relative to usage on pretraining data," recent work reduces "interference between new knowledge and the model's existing capabilities" (Lin et al., 2025). The results are dramatic: "using only 0.5% of activated parameters, our model achieves superior continual learning performance" with "forgetting reduced by up to 64% compared to standard fine-tuning" (Lin et al., 2025).

The insight is architectural: memory layers are naturally sparse by design. When you teach a memory-augmented model about medieval European history, it activates memory slots related to that domain. When you later teach it about quantum computing, different slots activate. The sparsity creates implicit parameter isolation without explicit task boundaries.

Product key memory systems enable this to scale efficiently. By using "product of learned key embeddings" for memory addressing, they achieve logarithmic complexity in memory size (Lample et al., 2019). This enables "memory layers with only 12 layers [to outperform] baseline transformer model with 24 layers" while "training on dataset with up to 30 billion words" (Lample et al., 2019).

When to use memory-augmented architectures: When you need to scale to many tasks or large knowledge bases, when computational efficiency at inference time matters, and when you can invest in architectural changes upfront. The sparse memory approach also works as a drop-in enhancement: "sparse memory layer can be added to any model without architectural modifications" (Lin et al., 2025).

The RAG Alternative

Before declaring memory layers the solution, we should consider a competing approach: don't update parameters at all. Instead, retrieve relevant information at inference time.

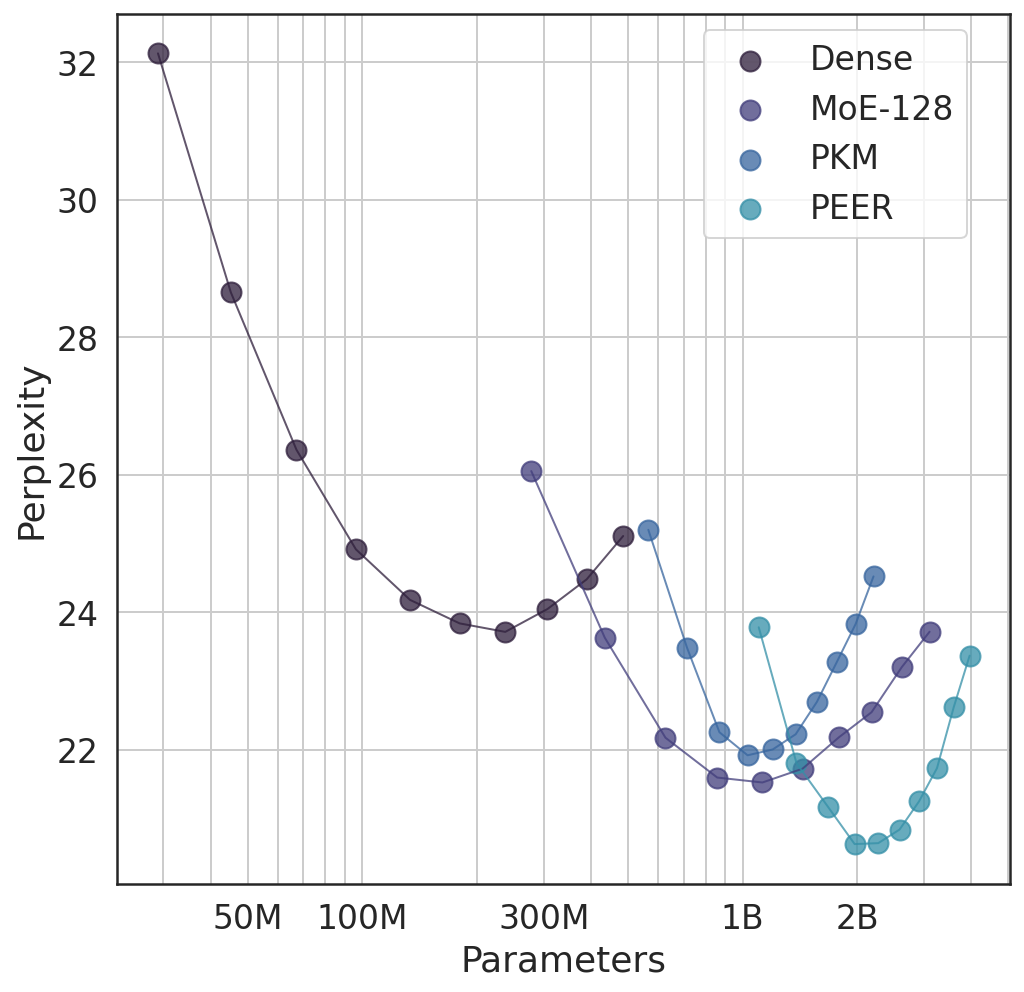

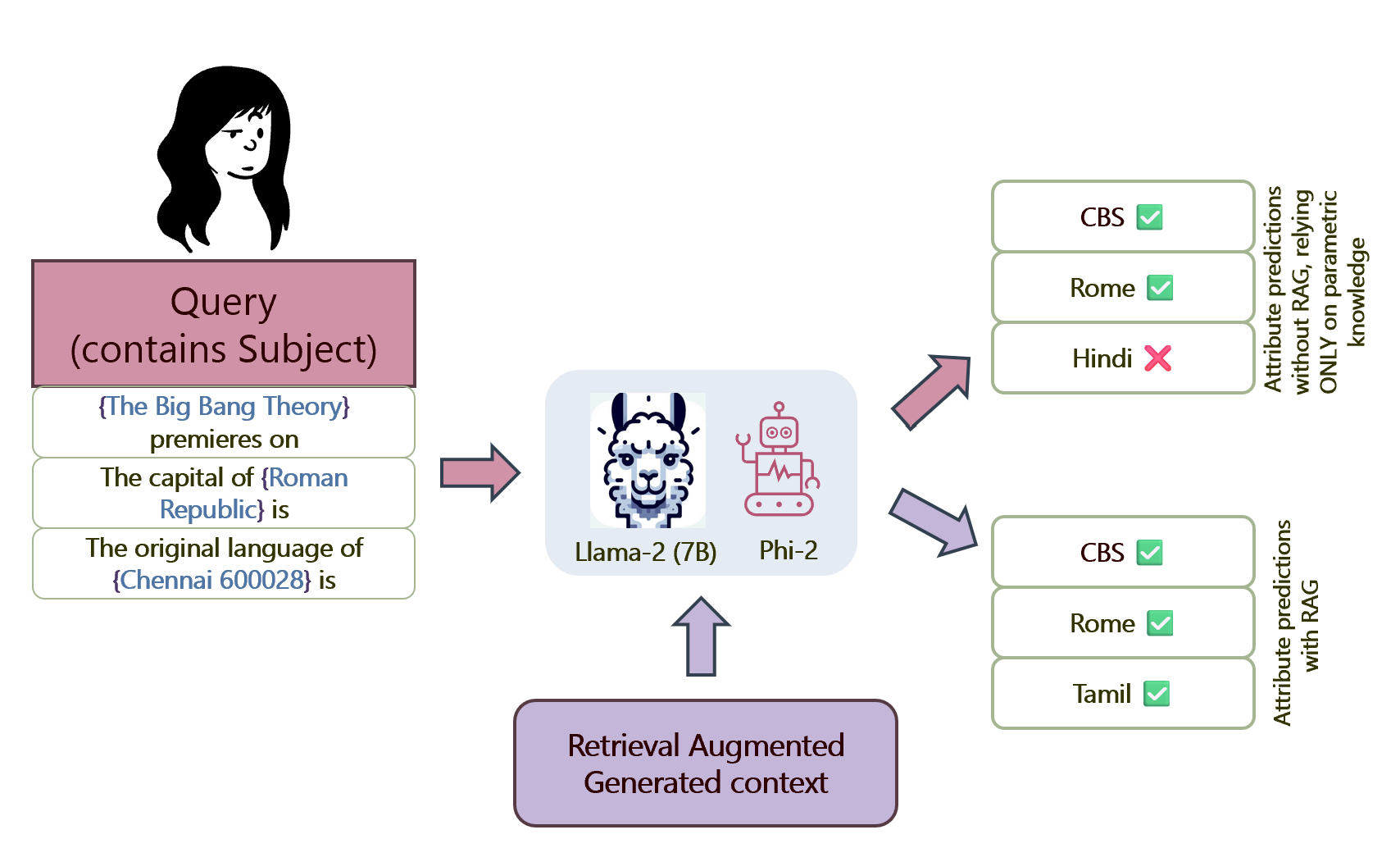

Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG) sidesteps catastrophic forgetting entirely by storing new knowledge in an external database rather than model parameters. Research shows that "RAG systems can reduce hallucinations by up to 70% on knowledge-intensive tasks" (Sen et al., 2024) by combining "parametric and non-parametric knowledge sources."

Figure 9: Comparison of model predictions with and without retrieval augmentation, demonstrating how RAG improves factual accuracy. Source: Sen et al., 2024

Figure 9: Comparison of model predictions with and without retrieval augmentation, demonstrating how RAG improves factual accuracy. Source: Sen et al., 2024

The trade-offs are instructive. RAG "surpasses fine-tuning by large margin particularly for least popular factual knowledge" (Zellers et al., 2024), making it ideal for tail knowledge that would be hard to encode reliably in parameters anyway. But RAG adds inference latency, requires maintaining a retrieval index, and cannot improve model capabilities, only knowledge.

Figure 10: Layer-wise analysis showing how different layers contribute to knowledge retrieval, with implications for where parametric vs retrieved knowledge is processed. Source: Sen et al., 2024

Figure 10: Layer-wise analysis showing how different layers contribute to knowledge retrieval, with implications for where parametric vs retrieved knowledge is processed. Source: Sen et al., 2024

For production systems, the choice often comes down to the nature of the knowledge. Factual knowledge that might change? RAG. Behavioral or capability improvements? Fine-tuning with continual learning methods. Many systems use both.

When to use RAG: When your knowledge is primarily factual and might change frequently, when you can tolerate retrieval latency, and when you want to avoid model updates entirely. RAG is not a continual learning method; it is a way to avoid needing one.

Model Merging: Post-Hoc Composition

A recent thread of work approaches continual learning from an entirely different angle: train specialized models independently, then merge them after the fact.

Task arithmetic treats "parameter updates as vectors in weight space, enabling linear combination of specialized models" (Evci et al., 2024). Train individual models on individual tasks, then combine their weight differences from the base model through linear combination. No sequential training, no forgetting during training.

The Localize-and-Stitch approach refines this by "identifying tiny localized regions" containing task-specific skills. Remarkably, "by localizing only 1% of parameters at sparsity level 0.01 our approach recovers 99% of finetuned performance" while dramatically reducing parameter conflicts (Evci et al., 2024). The finding reveals something important: "localized regions with 1% of total parameters have Jaccard similarity below 5%" across different tasks. In other words, different tasks naturally use almost entirely different parameter subsets, with less than 5% overlap.

The efficiency implications are significant. "Simple averaging, task arithmetic, and TIES-Merging can be implemented without additional data" (Evci et al., 2024), unlike methods like Fisher merging which "requires over 256 data points per task" or RegMean which needs "more than 1600 data points per task to compute inner product matrices."

Model merging can also preserve "90% of individual task performance while combining 5+ tasks" (Yang et al., 2025), suggesting that post-hoc composition might be a viable alternative to online continual learning in some settings.

When to use model merging: When you can train task-specific experts independently, when you want to avoid sequential training complexity entirely, and when tasks are sufficiently different that their task vectors have low overlap.

Comparing the Approaches

Each method makes different bets about how to resolve the stability-plasticity trade-off. The following table summarizes the key characteristics:

| Method | Forgetting Rate | Memory Cost | Compute Cost | Best For |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Full Fine-tuning | 89% | Low | Low | Single task, no prior knowledge needed |

| LoRA | 71% | Low | Low | Few tasks, moderate forgetting acceptable |

| EWC/Regularization | ~50-60% | Medium | Medium | Moderate task count, simplicity valued |

| Progressive Networks | 0% | High (grows linearly) | High | Few tasks, zero forgetting required |

| PackNet | 0% | Medium (fixed) | Medium | Moderate tasks, fixed model size |

| Memory Layers | 11% | Medium | Low at inference | Many tasks, efficiency critical |

| RAG | N/A (external) | High (retrieval index) | Medium | Factual knowledge, frequent updates |

| Model Merging | ~10% | Low | Medium | Independent training possible |

Table 1: Comparison of continual learning approaches. Forgetting rates for Full Fine-tuning (89%), LoRA (71%), and Memory Layers (11%) from Lin et al. (2025). Progressive Networks and PackNet achieve 0% by design. EWC (~50-60%) and Model Merging (~10%) estimated from related literature.

What We Don't Know Yet

Despite substantial progress, honest assessment requires acknowledging what remains unsolved.

Evaluation is harder than it looks. The TRACE benchmark provides "8 distinct datasets spanning challenging tasks" including "domain-specific tasks, multilingual capabilities, code generation, and mathematical reasoning" (Wu et al., 2023). But even comprehensive benchmarks struggle to capture real-world deployment dynamics. Most papers evaluate on controlled task sequences; production systems face non-stationary distributions, concept drift, and task boundaries that are rarely clear.

Current methods still "significantly lag behind joint training on all tasks" (Wu et al., 2023). If you have all your data upfront, train on it jointly. Continual learning methods accept worse absolute performance in exchange for the ability to learn sequentially. Whether this trade-off is acceptable depends heavily on the application.

Scaling beyond current model sizes remains uncertain. While UltraMem reaches 120B total parameters with 2.5B activated, achieving "99.5% of dense model performance with 10x parameter efficiency" (Huang et al., 2024), evaluation of memory-augmented approaches on 500B+ parameter models remains limited. The sparse memory approach that works at 7B might behave differently at GPT-4 scale.

Multimodal continual learning is almost entirely unexplored. Vision-language models face additional challenges: how do you prevent a model from forgetting visual concepts while learning new linguistic tasks, or vice versa?

And theoretical understanding lags empirical results. We can demonstrate that sparse memory finetuning reduces forgetting, but we lack formal guarantees about when and why it works.

Practical Takeaways

For practitioners deploying LLMs in production:

If your knowledge updates are primarily factual: Consider RAG first. It avoids the forgetting problem entirely, handles tail knowledge well, and makes updates trivial. The latency cost may be acceptable depending on your application.

If you need capability improvements: Memory-augmented architectures offer the best current trade-off between forgetting prevention and learning capacity. The sparse memory approach "reduces forgetting by up to 64%" while "achieving near-identical knowledge acquisition to full finetuning" (Lin et al., 2025).

If you can train specialized models independently: Model merging provides a computationally efficient alternative. Localize-and-Stitch recovers 99% of performance with just 1% of parameters, and the approach scales to many tasks.

If you need guaranteed preservation: Parameter isolation methods like Progressive Networks provide zero-forgetting guarantees, but at the cost of model complexity growth.

If computational constraints dominate: Parameter regularization methods like EWC remain viable. They add minimal overhead and work with any architecture, even if forgetting reduction is less dramatic than newer approaches.

Looking Forward

The stability-plasticity dilemma has been a problem since neural networks were invented. What has changed is that we finally have architectures designed specifically to address it, rather than training tricks applied to standard architectures.

Memory-augmented models represent a shift in how we think about neural network capacity. Instead of asking "how do we prevent the model from overwriting important weights," we can ask "how do we give the model dedicated space for new knowledge that doesn't interfere with existing capabilities." The answers to these questions lead to very different solutions.

The question that originally felt intractable, can models maintain stable knowledge while staying plastic enough for new learning, now has a partial answer: yes, if you build them with architectural support for it. The 11% forgetting achieved by sparse memory finetuning, compared to 89% for full finetuning, represents genuine progress.

I suspect the most successful production systems will combine approaches: memory augmentation for capability improvements that need to be internalized, RAG for factual knowledge that might change, and model merging for combining specialized fine-tunes. The field is converging toward hybrid architectures, even if the optimal combinations remain to be worked out.

For researchers, the open problems are substantial. Better evaluation protocols that capture real-world deployment dynamics. Theoretical understanding of why sparse memory works. Scaling studies on frontier-scale models. Multimodal continual learning. The stability-plasticity dilemma may be old, but the solutions are young and evolving rapidly.

I would genuinely appreciate hearing how others are thinking about this problem. What trade-offs are you making in production? Which approaches have surprised you, positively or negatively? The field advances through practitioners sharing what works.

References

-

Asai, S. et al. (2024). EVCL: Elastic Variational Continual Learning with Weight Consolidation. arXiv:2406.15972. https://arxiv.org/abs/2406.15972

-

Chaudhry, A. et al. (2021). Stabilizing Elastic Weight Consolidation for Practical ML Tasks. arXiv:2109.10021. https://arxiv.org/abs/2109.10021

-

Evci, U. et al. (2024). Efficient Model Merging via Sparse Task Arithmetic. arXiv:2408.13656. https://arxiv.org/abs/2408.13656

-

Graves, A. et al. (2014). Neural Turing Machines. arXiv:1410.5401. https://arxiv.org/abs/1410.5401

-

He, X. et al. (2024). PEER: Product Key Memory-Augmented Architecture. arXiv:2407.04153. https://arxiv.org/abs/2407.04153

-

Huang, Y. et al. (2024). UltraMemV2: Memory Networks Scaling to 120B Parameters. arXiv:2508.18756. https://arxiv.org/abs/2508.18756

-

Kirkpatrick, J. et al. (2017). Overcoming Catastrophic Forgetting in Neural Networks. PNAS. arXiv:1612.00796. https://arxiv.org/abs/1612.00796

-

Lample, G. et al. (2019). Product Key Memory Systems. arXiv:1907.05242. https://arxiv.org/abs/1907.05242

-

Lin, J. et al. (2025). Continual Learning via Sparse Memory Finetuning. arXiv:2510.15103. https://arxiv.org/abs/2510.15103

-

Luo, Y. et al. (2023). An Empirical Study of Catastrophic Forgetting in Large Language Models During Continual Fine-tuning. arXiv:2308.08747. https://arxiv.org/abs/2308.08747

-

Mallya, A. & Lazebnik, S. (2017). PackNet: Adding Multiple Tasks to a Single Network by Iterative Pruning. CVPR. arXiv:1711.05769. https://arxiv.org/abs/1711.05769

-

Rusu, A. et al. (2016). Progressive Neural Networks. ICML. arXiv:1606.04671. https://arxiv.org/abs/1606.04671

-

Sen, A. et al. (2024). From RAGs to Rich Parameters: Probing Language Model Knowledge Utilization. arXiv:2406.12824. https://arxiv.org/abs/2406.12824

-

Weston, J. et al. (2015). Memory Networks. ICLR. arXiv:1503.08895. https://arxiv.org/abs/1503.08895

-

Wu, T. et al. (2024). Continual Learning for Large Language Models: A Survey. arXiv:2402.01364. https://arxiv.org/abs/2402.01364

-

Wu, T. et al. (2023). TRACE: A Comprehensive Benchmark for Continual Learning in Large Language Models. arXiv:2310.06762. https://arxiv.org/abs/2310.06762

-

Yang, X. et al. (2025). Merging Models on the Fly: A Sequential Approach to Scalable Continual Model Merging. arXiv:2501.09522. https://arxiv.org/abs/2501.09522

-

Zellers, R. et al. (2024). Quantifying Reliance on External Information Over Parametric Knowledge During RAG. arXiv:2410.00857. https://arxiv.org/abs/2410.00857