The Dark Matter of Biology: What Machine Learning Reveals About the Invisible Proteome

If you mapped the human proteome using traditional structural biology tools, you would miss about a third of it. Not because these proteins do not exist, but because they refuse to hold still long enough to be measured.

"Intrinsically disordered proteins (IDPs), comprising 30-40% of the proteome, are critical in diseases including neuro-degenerative disorders and cancer."1 These proteins do not fold into neat 3D structures. They remain flexible, dynamic, constantly shifting between conformations. For traditional structural biology, which depends on crystallizing molecules and photographing them with X-rays, intrinsically disordered proteins were essentially invisible. You cannot crystallize something that will not hold a fixed shape.

This was biology's dark matter problem: components that clearly exist, that obviously have function, but that our primary measurement tools could not capture. The analogy holds remarkably well. Astronomers inferred dark matter's existence from its gravitational effects long before they could detect it directly. Biologists did something similar with intrinsic disorder, inferring its presence from functional effects while struggling to characterize it directly.

Machine learning changed the equation. When transformer-based models trained on massive sequence databases began making predictions, they started revealing patterns that structural biology missed. The dark matter of biology was becoming visible. For context on how these foundation models work across different biological domains, see Foundation Models Are Rewriting the Rules of Biology. The catch? We are still figuring out how to measure whether what we see is actually real.

The Parts We Could Not See

The invisibility of intrinsic disorder was not a minor oversight. It was baked into how biology studied molecular structure.

Consider the numbers. "Over 85% of the human genome is transcribed, but a mere 3% encodes proteins."2 The remaining 82% produces non-coding RNAs, regulatory elements, and structural domains that traditional genomics largely treated as noise. Similarly with proteins: "80% of human cancer-associated proteins have long IDRs (e.g., p53 contains 50% IDR in its sequence)."3

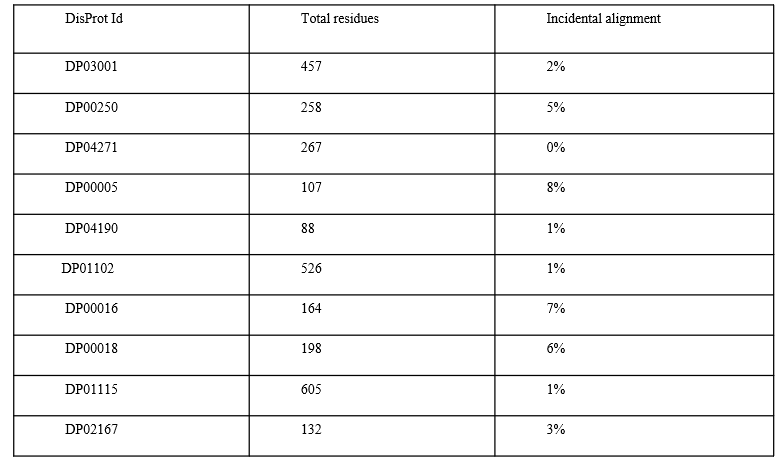

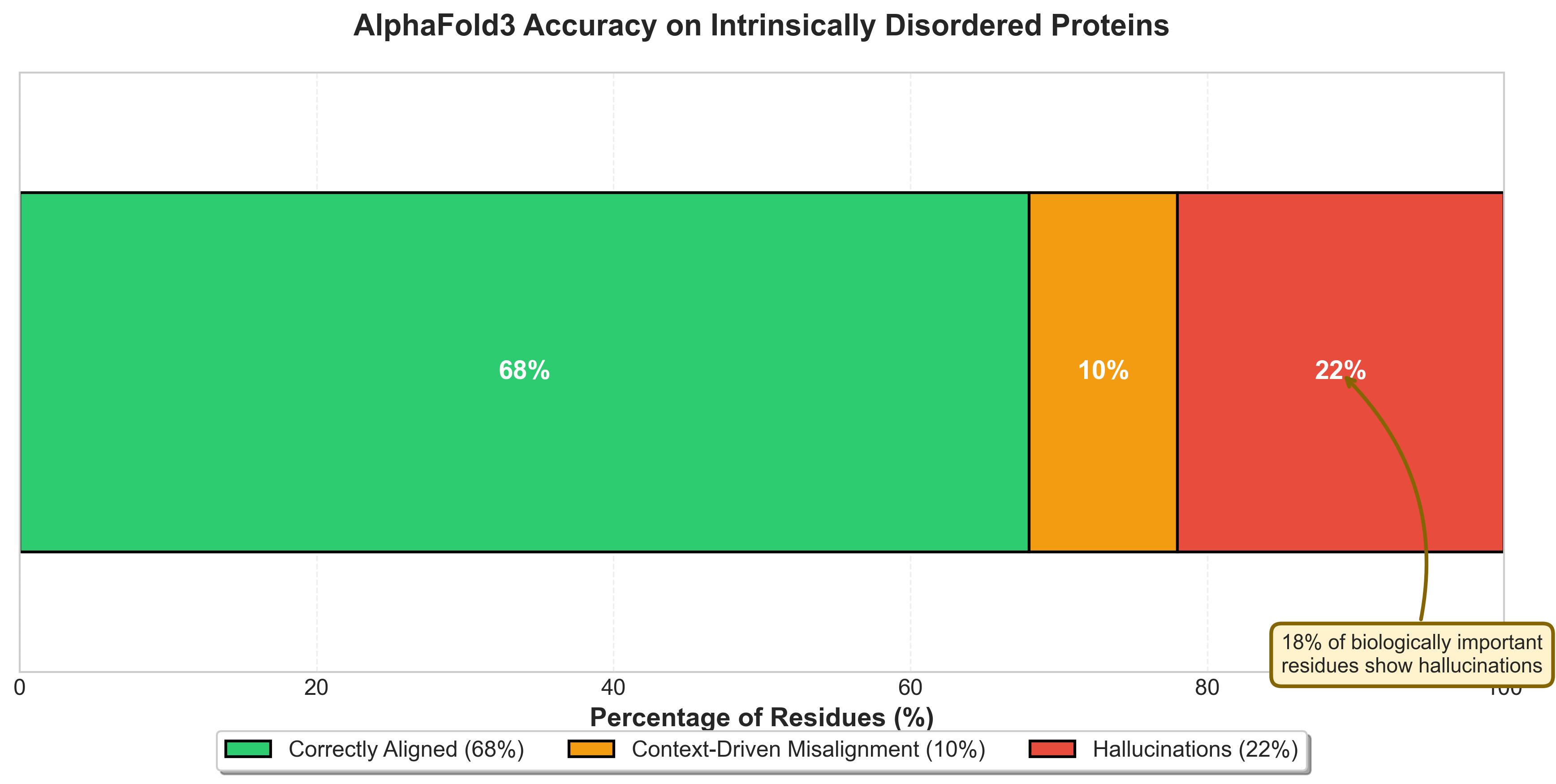

Figure 1: AlphaFold3's challenges with intrinsically disordered proteins. Quantitative evidence that structure prediction struggles with disorder. Source: AlphaFold3 IDP Hallucinations study1

Figure 1: AlphaFold3's challenges with intrinsically disordered proteins. Quantitative evidence that structure prediction struggles with disorder. Source: AlphaFold3 IDP Hallucinations study1

These are not edge cases. The p53 tumor suppressor, one of the most studied proteins in cancer biology, is half disordered. The tau protein implicated in Alzheimer's disease is almost entirely disordered in its native state. The transcription factors that control gene expression, the signaling proteins that coordinate immune responses: all rely on intrinsic disorder to do their jobs.

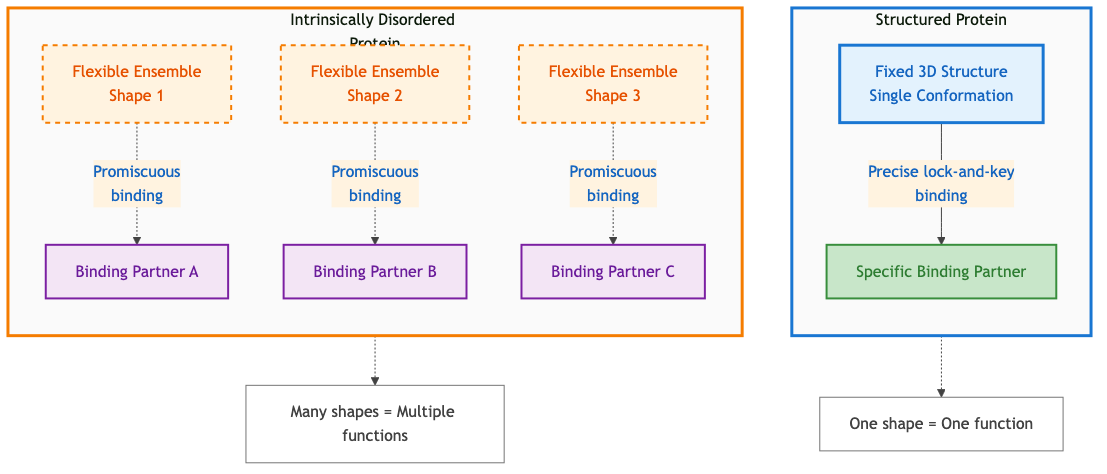

The term "dark matter" fits surprisingly well. "Intrinsically disordered regions (IDRs) of the IDP offers the scope to interact with multiple targets."4 This flexibility is their function. A disordered region can bind multiple different partners, enabling the protein to act as a hub in cellular signaling networks. Their disorder is not a bug; it is the mechanism.

Figure 4: Comparison of structured proteins (fixed shape, specific binding) versus intrinsically disordered proteins (flexible conformations, multiple binding partners). Disorder enables functional versatility through promiscuous binding. Diagram by author based on principles in 4.

Figure 4: Comparison of structured proteins (fixed shape, specific binding) versus intrinsically disordered proteins (flexible conformations, multiple binding partners). Disorder enables functional versatility through promiscuous binding. Diagram by author based on principles in 4.

Traditional experimental techniques created a profound selection bias. We built our understanding of molecular biology from what we could see clearly: stable, well-folded proteins in isolation. The dynamic, flexible, context-dependent components got relegated to footnotes. "RNA-only structures comprise less than 1.0% of the ~214,000 structures in the Protein Data Bank (PDB), and RNA-containing complexes account for only 2.1%."5

The vicious cycle was clear: without structural data, we could not build good models; without good models, we could not validate new structures; without validation, experimentalists did not know where to focus. Machine learning promised to break this cycle by learning directly from sequence, bypassing the need for experimental structures. But that promise depends on having benchmarks robust enough to tell us when the models are actually working.

When Machine Learning Started Looking

Machine learning changed the game because it does not need to see structure directly. It learns from sequence.

The key insight: proteins with similar sequences in disordered regions often have similar functions, even if they never adopt stable structures. The amino acid composition matters. The charge patterns matter. The flexibility itself becomes functional information that machine learning can detect.

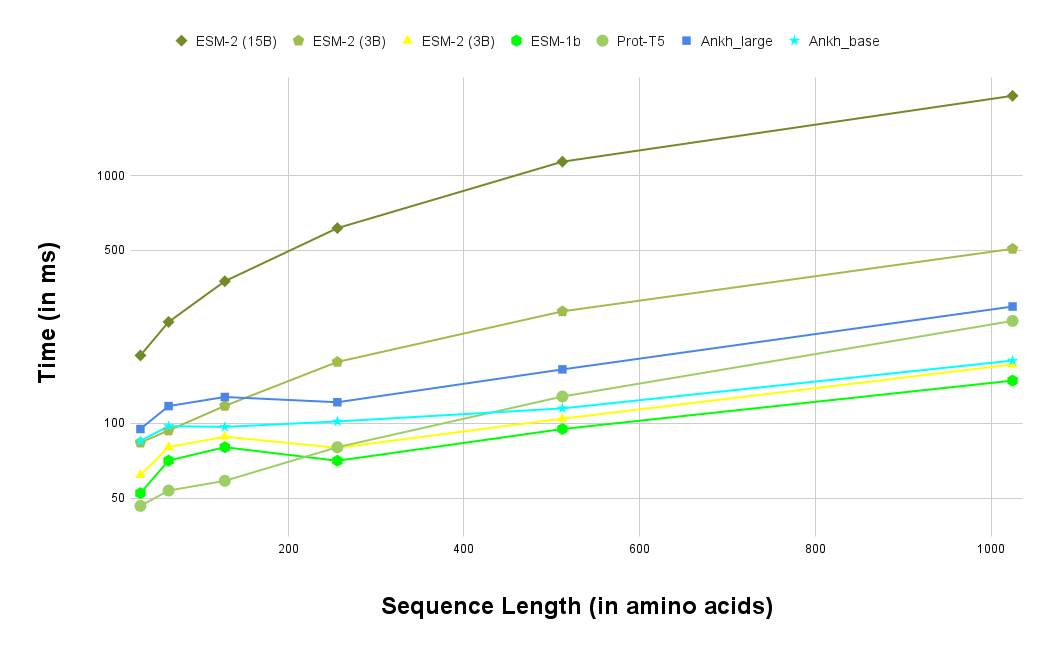

Figure 2: Performance comparison of protein language models across different sequence lengths. Models are learning to extract structural information from sequence alone. Source: Ankh Protein Language Model paper6

Figure 2: Performance comparison of protein language models across different sequence lengths. Models are learning to extract structural information from sequence alone. Source: Ankh Protein Language Model paper6

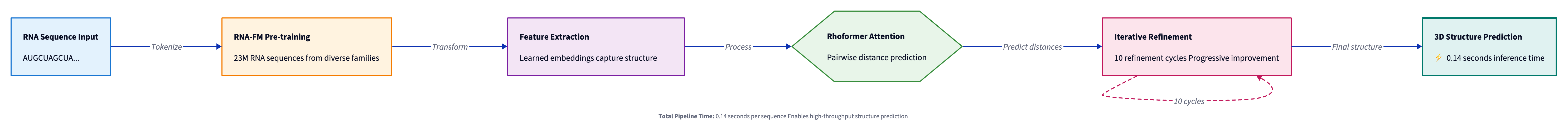

For RNA, the breakthrough came with RhoFold and its successor RhoFold+. In the RNA-Puzzles competition, "RhoFold+ produced an average RMSD of 4.02 A, 2.30 A better than that of the second-best model (FARFAR2: top 1%, 6.32 A)."7 This was not incremental improvement. This was a 36% reduction in error compared to the previous best method.

The model achieved this using "an RNA language model (RNA-FM) pre-trained on 23,735,169 unannotated RNA sequences."8 Speed mattered too: "RhoFold+ can generate valid and largely accurate RNA 3D structures of interest typically within ~0.14 seconds (w/o MSA searching)."9 Sub-second prediction for structures that might have taken weeks of experimental work.

Figure 5: RNA foundation model pipeline from sequence input through pre-training, feature extraction, Rhoformer attention, iterative refinement, to 3D structure prediction in 0.14 seconds. Diagram by author based on RhoFold+ architecture.7

Figure 5: RNA foundation model pipeline from sequence input through pre-training, feature extraction, Rhoformer attention, iterative refinement, to 3D structure prediction in 0.14 seconds. Diagram by author based on RhoFold+ architecture.7

For genomics more broadly, OmniGenome demonstrated that incorporating structural information into sequence models pays dividends. "OmniGenome significantly outperforms other models on the mRNA degradation rate prediction task, achieving an RMSE of 0.7121, compared to the second-best RMSE of 0.7297 by RNA-FM."10 And "for the SNMD task, OmniGenome achieves an AUC of 64.13, surpassing the second-best score of 59.02 by RNA-FM."11

The fundamental insight: evolutionary information encoded in sequences contains structural signals. With enough data and the right architecture, models can learn to decode those signals for structures we have never directly observed.

Where Models Still Hallucinate

But visibility does not mean perfect clarity. AlphaFold, despite its remarkable success on ordered proteins, struggles with disorder in revealing ways.

A recent study examined AlphaFold3's predictions for 72 proteins from the DisProt database. "DisProt is the primary database manually curated and annotated with experimental results for IDPs and IDRs and has evolved with over 3000 IDPs."12 The results were sobering: "32 percent of residues are misaligned with DisProt, with 22 percent representing hallucinations where AlphaFold3 incorrectly predicts order in disordered regions or vice versa."13

Twenty-two percent hallucinations. That is not a minor calibration issue. That is a fundamental mismatch between what the model learned and what intrinsic disorder actually is.

Figure 6: AlphaFold3 prediction breakdown on intrinsically disordered proteins: 68% correctly aligned, 10% context-driven misalignment, 22% hallucinations. Critically, 18% of biologically important residues show hallucinations.14

Figure 6: AlphaFold3 prediction breakdown on intrinsically disordered proteins: 68% correctly aligned, 10% context-driven misalignment, 22% hallucinations. Critically, 18% of biologically important residues show hallucinations.14

Even more concerning: "18 percent of residues associated with biological processes showed hallucinations."14 When researchers looked specifically at regions known to be functionally important (binding sites, modification sites, regions critical for protein-protein interactions), AlphaFold was more likely to get them wrong.

"More than 50% of the proteins had less than 70% alignment with DisProt."15 For half the test set, AlphaFold's disorder predictions were wrong more often than they were right.

My hypothesis: AlphaFold learned structure from the Protein Data Bank, which is overwhelmingly ordered proteins or ordered regions of proteins. The model learned that amino acid sequences correspond to specific structural configurations. For disordered proteins, there is no single structural configuration. The model, encountering this ambiguity, falls back on structural priors that do not apply. It predicts order because that is what its training data represented. For a deeper understanding of what AlphaFold's embeddings actually encode and their downstream applications, see From Structure to Function: Leveraging AlphaFold's Evoformer Embeddings for Downstream AI.

"The pLDDT is a confidence score that indicates the reliability of the structural predictions for each residue, with scores above 70 typically considered to indicate high confidence."16 But pLDDT scores calibrated on well-folded domains do not necessarily transfer to intrinsically disordered regions. High confidence does not mean correct when you are extrapolating beyond your training distribution. The model can be confidently wrong, predicting rigid structure where flexibility is the actual function.

The Benchmark Gap

This brings us to a deeper problem: we are finally able to see the dark matter of biology, but we do not have good ways to measure how well we are seeing it.

For protein structure prediction, we have CASP (Critical Assessment of protein Structure Prediction), running since 1994. For RNA? Until recently, almost nothing comparable existed. The field lacked systematic benchmarks across the diversity of RNA structure and function problems.

BEACON attempts to fill this gap. The benchmark encompasses diverse tasks spanning structural analysis, functional studies, and engineering applications specifically for RNA.17 It covers secondary structure prediction, tertiary structure prediction, RNA-protein binding, RNA modifications, and RNA design tasks.

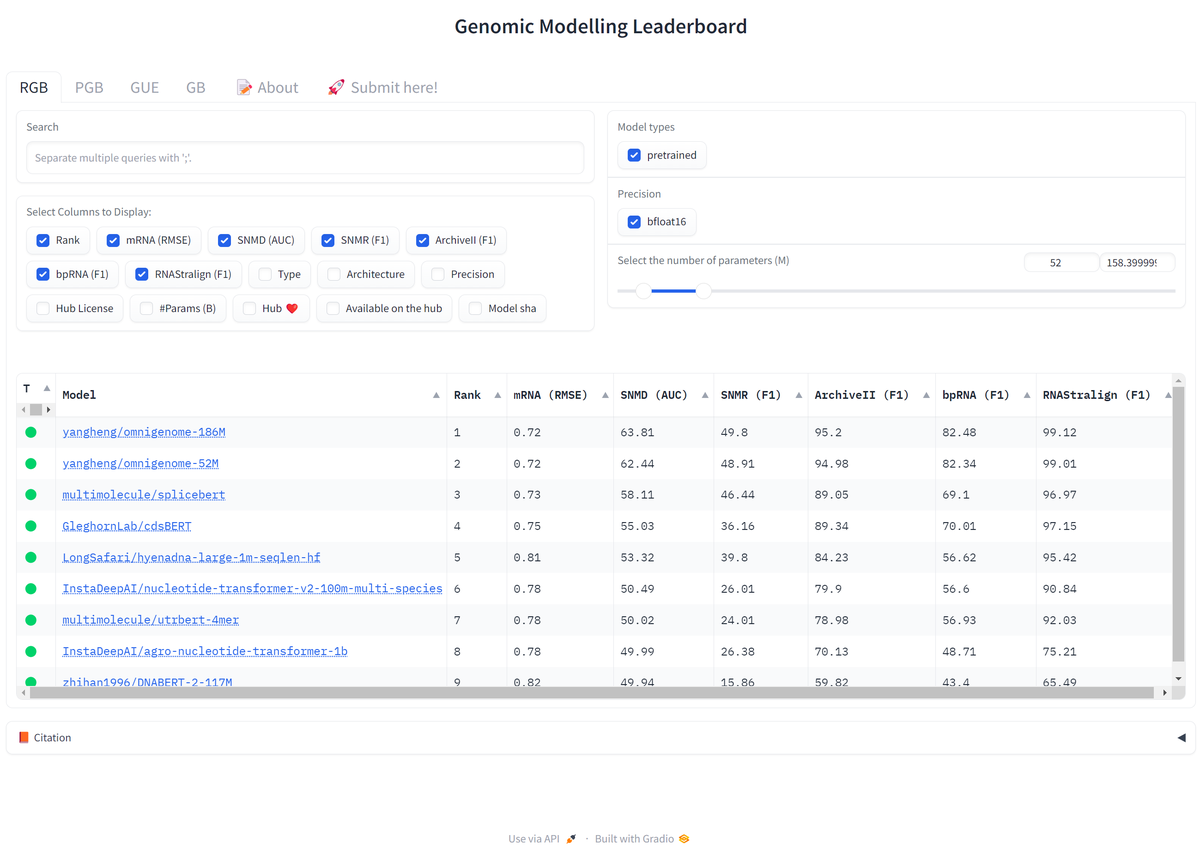

Figure 3: Genomic Modeling Leaderboard comparing state-of-the-art foundation models across multiple benchmarks. The competitive landscape is rapidly evolving. Source: OmniGenBench paper18

Figure 3: Genomic Modeling Leaderboard comparing state-of-the-art foundation models across multiple benchmarks. The competitive landscape is rapidly evolving. Source: OmniGenBench paper18

The benchmark revealed interesting patterns. "In the secondary structure prediction tasks (Archive2, Stralign, bpRNA), OmniGenome demonstrates superior performance."19 But performance varies dramatically across tasks. Models that excel at secondary structure prediction often struggle with functional tasks like splice site identification or binding partner prediction.

# Example: Evaluating RNA secondary structure prediction

# Note: This is a simplified example - actual BEACON uses standardized datasets

import numpy as np

def evaluate_rna_structure(predicted: str, ground_truth: str) -> dict:

"""

Calculate structure prediction metrics.

predicted/ground_truth: dot-bracket notation (e.g., "(((...)))")

"""

# Count true/false positives/negatives for base pairs

tp = sum(1 for p, g in zip(predicted, ground_truth)

if p in '()' and p == g)

fp = sum(1 for p, g in zip(predicted, ground_truth)

if p in '()' and g == '.')

fn = sum(1 for p, g in zip(predicted, ground_truth)

if p == '.' and g in '()')

sensitivity = tp / (tp + fn) if (tp + fn) > 0 else 0

ppv = tp / (tp + fp) if (tp + fp) > 0 else 0 # Positive predictive value

f1 = 2 * sensitivity * ppv / (sensitivity + ppv) if (sensitivity + ppv) > 0 else 0

return {"sensitivity": sensitivity, "ppv": ppv, "f1": f1}

# Example evaluation

pred = "(((.....)))..((...))"

true = "(((.....)))(((...)))"

metrics = evaluate_rna_structure(pred, true)

print(f"Sensitivity: {metrics['sensitivity']:.2f}") # Recall of paired bases

print(f"PPV: {metrics['ppv']:.2f}") # Precision of predictions

print(f"F1: {metrics['f1']:.2f}") # Harmonic mean

# Output: Sensitivity: 0.75, PPV: 0.90, F1: 0.82

This variation points to a deeper problem: we are not just lacking data; we are lacking diverse data. Most RNA structural data comes from ribosomal RNAs and transfer RNAs, ancient and highly conserved molecules. Regulatory RNAs, long non-coding RNAs, and ribozymes remain underrepresented. A model might perform well on BEACON's structure tasks simply because those tasks resemble the training data, while failing on functional tasks that require understanding RNA's biological context.

"Despite decades of advancements in molecular biology, deciphering genomes remains a significant challenge."20 "The central dogma of biology posits that genomes, including DNA and RNA, encode and transmit the genetic information essential for all living systems and underpin the translation of proteins."21 But real biology is messier than the central dogma suggests. Consider microRNAs: they are encoded by DNA, transcribed to RNA, but then regulate protein translation by binding to other RNAs, creating circular feedback loops that a linear model cannot capture. These context-dependent interactions appear at every scale.

Four Open Problems

The gap between what machine learning can theoretically address and what we can actually measure is growing. Several challenges remain unsolved:

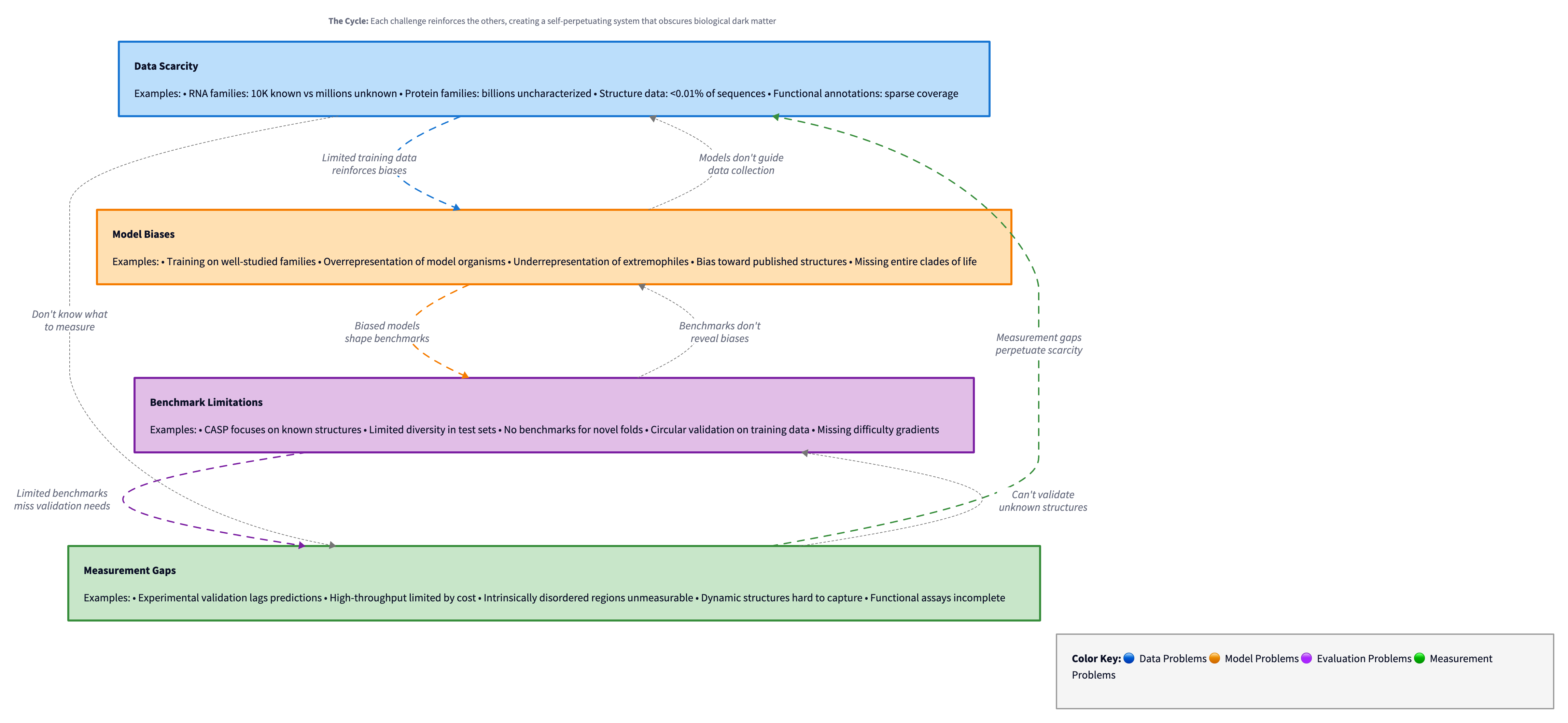

Dynamics versus snapshots. Intrinsically disordered proteins are dynamic by nature. They do not adopt a single structure; they sample an ensemble of conformations. "7.6% of the aligned residues were involved in structural transition."22 Current benchmarks typically compare against single experimental snapshots, missing the temporal dimension entirely. A model might perfectly predict one snapshot but completely miss the conformational ensemble that defines biological function.

Function without structure. Many disordered proteins function through transient interactions that do not produce stable, crystallizable complexes. A model might perfectly predict that a region is disordered but completely miss what that region does. "30% did not show hallucinations at segments known to have a biological context."23 But that means 70% of biologically relevant segments had some degree of prediction error. We need functional benchmarks that test whether models understand binding specificity, signaling dynamics, or regulatory mechanisms, not just structural disorder per se.

Cross-modal understanding. Biology does not separate into neat categories. Proteins interact with RNA. RNA forms complexes with proteins. Disordered regions often mediate these interactions. "GFMs incorporating structural context, like OmniGenome, can generalize effectively across different genomic modalities (RNA and DNA) and species (plants)."24 But current benchmarks typically evaluate proteins and RNA separately. "GB includes 9 datasets focusing on various regulatory elements, such as promoters, enhancers, and open chromatin regions, across different species like humans, mice, and roundworms."25 The integration challenge remains largely unaddressed.

Rare but important cases. Drug targets are often unusual proteins with unique properties. A benchmark dominated by common, well-characterized proteins might miss the edge cases that matter most for applications. "8% of the proteins show a higher degree of hallucination (60-80%) at the regions involved in biological processes."26 These high-error-rate proteins are not outliers to be excluded from benchmarks. They are precisely the cases where better models could make the biggest impact.

Figure 7: The self-reinforcing cycle of challenges in biological dark matter prediction: data scarcity leads to model biases, which expose benchmark limitations, which reveal measurement gaps, which perpetuate data scarcity. Diagram by author.

Figure 7: The self-reinforcing cycle of challenges in biological dark matter prediction: data scarcity leads to model biases, which expose benchmark limitations, which reveal measurement gaps, which perpetuate data scarcity. Diagram by author.

What Good Benchmarks Would Look Like

What would better benchmarks for biological dark matter actually require?

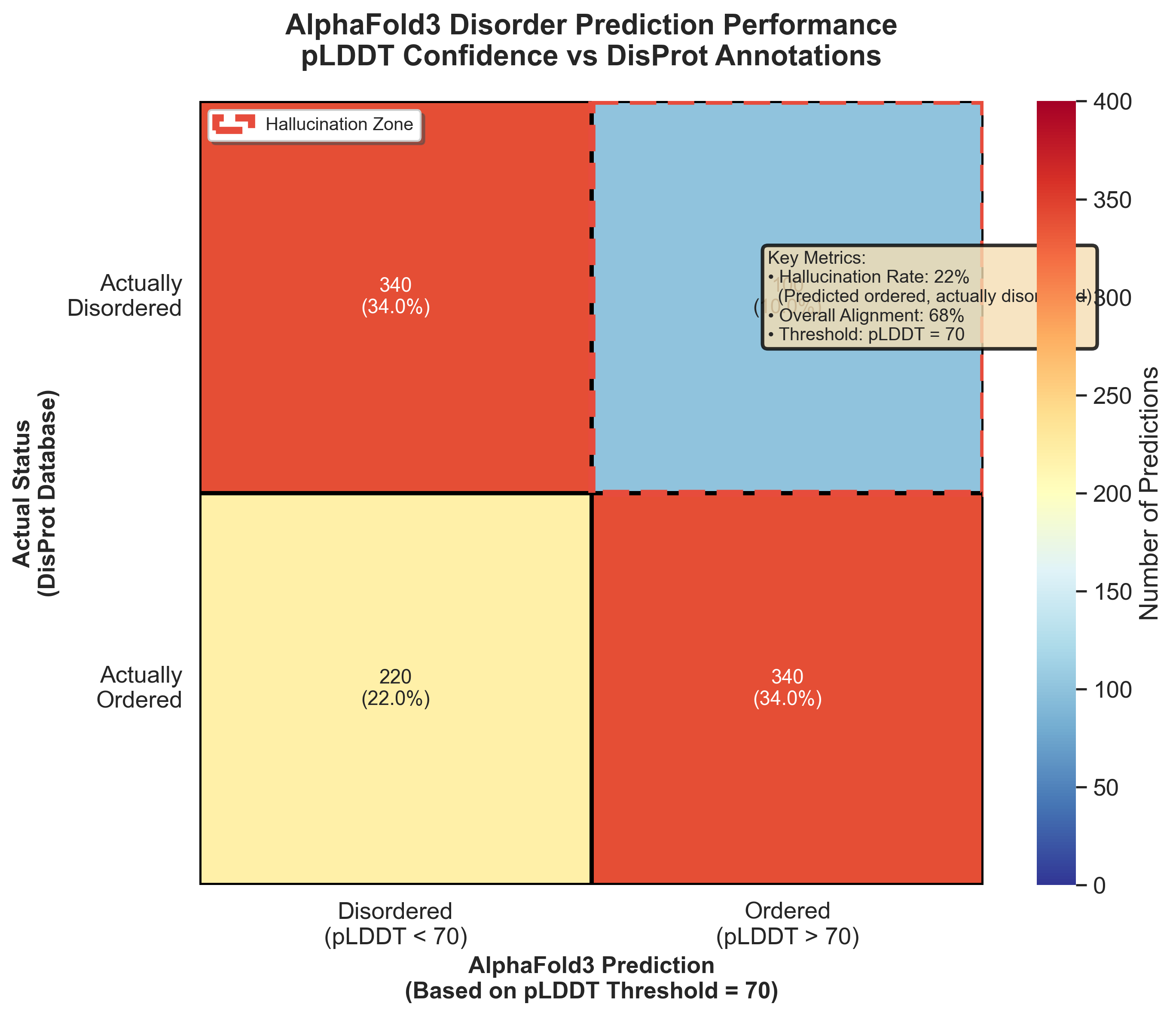

First, coverage. If intrinsically disordered proteins represent 30-40% of the proteome, and "the number of IDP documented in DisProt is approximately 3000"27 while "the human proteome has approx 20000 protein-coding genes,"28 we have experimental annotations for perhaps 15% of all IDPs. The benchmark can only be as comprehensive as our experimental knowledge.

Second, biological context. "Comparison of predictions (ordered/disordered) in the native state with predictions in the context-based state from AF3 revealed that the latter results aligned with the former in 89% of residues."29 These conformational changes, from disorder to order upon binding or vice versa, are central to IDP function. A static benchmark that evaluates single-structure predictions will systematically miss dynamic behavior.

Figure 8: AlphaFold3's disorder prediction accuracy versus DisProt annotations. The highlighted zone shows where AlphaFold predicted ordered structure for actually disordered proteins, accounting for 22% of IDP predictions.13

Figure 8: AlphaFold3's disorder prediction accuracy versus DisProt annotations. The highlighted zone shows where AlphaFold predicted ordered structure for actually disordered proteins, accounting for 22% of IDP predictions.13

Third, functional validation. "18% of the residues involved in the biological processes showed hallucinations."30 Prediction accuracy is not uniformly distributed. Some proteins are easier to predict than others. Some regions matter more for function than others. A benchmark that treats all predictions equally may miss functionally critical failure modes.

The five criteria for better benchmarks:

-

Dynamic evaluation: Benchmarks that test conformational changes, not just static structures. Can the model predict how a protein responds to binding partners, post-translational modifications, or environmental changes?

-

Functional validation: Metrics that correlate with biological activity. It is not enough to predict disorder; we need to predict function in disordered regions.

-

Negative controls: Systematic evaluation of failure modes. What kinds of errors do models make? Are there systematic biases? Do models hallucinate in predictable ways?

-

Integration tests: Evaluation of multi-scale predictions. Can sequence-level disorder predictions inform structural models? Can structural models inform functional predictions?

-

Uncertainty quantification: Calibrated confidence scores that actually reflect prediction reliability, particularly for extrapolation beyond training distributions.

The challenge is that creating these benchmarks requires solving the same scientific problems we are trying to use the models to address. We need experimental techniques that can measure dynamic behavior, functional activity, and multi-scale integration. If we had those techniques at scale, we would not need the models quite so desperately.

The Path Forward

The irony of machine learning in biology is that it reveals how much we do not know by showing us what our models cannot explain. Hallucinations in AlphaFold3's disorder predictions are not just prediction errors. They are evidence that our training data systematically misrepresents biological reality.

The solution is not better models alone, or better benchmarks alone. It is a tighter feedback loop between model development, benchmark design, and experimental validation. Models reveal blind spots in benchmarks. Benchmarks reveal blind spots in experimental techniques. Experiments reveal blind spots in models.

RNA structure prediction has benefited enormously from this feedback loop. RhoFold+ can generate structures within fractions of a second. That speed enables large-scale screening, which generates predictions that experimentalists can validate, which reveals model limitations, which informs next-generation architectures.

For intrinsic disorder, we are earlier in that cycle. We have models that make predictions, but experimental validation remains expensive and slow. "The generalizability of the study is constrained by its limited sample size (72 out of 3000+ DisProt proteins)."31 Scaling up validation will require better experimental techniques, perhaps computational validation, perhaps high-throughput functional assays, perhaps integration with other data modalities.

The benchmark gap is not a technical problem to be solved and moved past. It is a fundamental characteristic of applying machine learning to systems we do not yet fully understand. The models will always see things we cannot directly measure. The question is whether what they see is real biological signal or learned artifacts from biased training data.

BEACON, OmniGenBench, and similar efforts are essential not because they solve this problem but because they make it tractable. They provide shared evaluation frameworks that let researchers across labs and institutions compare approaches systematically. That standardization enables progress even when the underlying biology remains partially opaque.

Seeing in the Dark

The dark matter of biology is becoming visible through machine learning, but we are still learning to interpret what we see. Models trained on massive sequence databases extract patterns that traditional structural biology missed. Some of those patterns represent real biology: intrinsic disorder, RNA structure, weak interactions that our experimental techniques struggled to capture.

But some of what models see is not there. Hallucinations occur precisely because models extrapolate beyond their training distribution into regions of biological space we have not sampled experimentally. High confidence does not guarantee correctness when you are predicting something fundamentally different from what you were trained on.

The next generation of progress depends on better benchmarks: evaluation frameworks that capture dynamic behavior, functional relevance, and multi-scale integration. But creating those benchmarks requires solving exactly the problems we need the models for. We are measuring the dark matter of biology by its effects on things we can see, and trying to distinguish real signal from instrumental artifacts.

This is science at its most interesting: the moment when new tools reveal phenomena we could not observe before, but before we fully understand what we are observing. Machine learning has given biology the equivalent of gravitational lensing for dark matter. Now we need to figure out what we are actually looking at.

The parts of biology we could not see are finally becoming visible. Whether we can trust what we see, whether our models reveal genuine biological insight or sophisticated pattern-matching artifacts: that is the harder question, and the one that will determine whether this approach transforms biology or remains a promising technique with unclear applicability.

Closing that gap will take more than better models or more data. It will take new ways of doing science: tighter integration between computation and experiment, better tools for systematic validation, and honest acknowledgment that sometimes the most important discoveries are the ones that reveal how much we still do not understand.

References

Footnotes

-

Ghosh, D., et al. (2024). "Intrinsically disordered proteins (IDPs), comprising 30-40% of the proteome, are critical in diseases including neuro-degenerative disorders and cancer." AlphaFold3 IDP Hallucinations Study. bioRxiv. https://doi.org/10.1101/2024.08.05.606142 ↩ ↩2

-

Shen, T., et al. (2023). "Over 85% of the human genome is transcribed, but a mere 3% encodes proteins." RhoFold RNA 3D Structure Prediction. bioRxiv. https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.05.24.542159 ↩

-

Ghosh, D., et al. (2024). "80% of human cancer-associated proteins have long IDRs (e.g., p53 contains 50% IDR in its sequence)." AlphaFold3 IDP Hallucinations Study. bioRxiv. https://doi.org/10.1101/2024.08.05.606142 ↩

-

Ghosh, D., et al. (2024). "Intrinsically disordered regions (IDRs) of the IDP offers the scope to interact with multiple targets." AlphaFold3 IDP Hallucinations Study. bioRxiv. https://doi.org/10.1101/2024.08.05.606142 ↩ ↩2

-

Shen, T., et al. (2023). "RNA-only structures comprise less than 1.0% of the ~214,000 structures in the Protein Data Bank (PDB), and RNA-containing complexes account for only 2.1%." RhoFold RNA 3D Structure Prediction. bioRxiv. https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.05.24.542159 ↩

-

Elnaggar, A., et al. (2023). Ankh Protein Language Model. bioRxiv. https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.01.16.524265 ↩

-

Shen, T., et al. (2023). "RhoFold+ produced an average RMSD of 4.02 A, 2.30 A better than that of the second-best model (FARFAR2: top 1%, 6.32 A)." RhoFold RNA 3D Structure Prediction. bioRxiv. https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.05.24.542159 ↩ ↩2

-

Shen, T., et al. (2023). "Using an RNA language model (RNA-FM) pre-trained on 23,735,169 unannotated RNA sequences." RhoFold RNA 3D Structure Prediction. bioRxiv. https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.05.24.542159 ↩

-

Shen, T., et al. (2023). "RhoFold+ can generate valid and largely accurate RNA 3D structures of interest typically within ~0.14 seconds (w/o MSA searching)." RhoFold RNA 3D Structure Prediction. bioRxiv. https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.05.24.542159 ↩

-

Zhang, J., et al. (2024). "OmniGenome significantly outperforms other models on the mRNA degradation rate prediction task, achieving an RMSE of 0.7121, compared to the second-best RMSE of 0.7297 by RNA-FM." OmniGenBench Genomic Foundation Models. arXiv. https://arxiv.org/abs/2410.01784 ↩

-

Zhang, J., et al. (2024). "For the SNMD task, OmniGenome achieves an AUC of 64.13, surpassing the second-best score of 59.02 by RNA-FM." OmniGenBench Genomic Foundation Models. arXiv. https://arxiv.org/abs/2410.01784 ↩

-

Ghosh, D., et al. (2024). "DisProt is the primary database manually curated and annotated with experimental results for IDPs and IDRs and has evolved with over 3000 IDPs." AlphaFold3 IDP Hallucinations Study. bioRxiv. https://doi.org/10.1101/2024.08.05.606142 ↩

-

Ghosh, D., et al. (2024). "32 percent of residues are misaligned with DisProt, with 22 percent representing hallucinations where AlphaFold3 incorrectly predicts order in disordered regions or vice versa." AlphaFold3 IDP Hallucinations Study. bioRxiv. https://doi.org/10.1101/2024.08.05.606142 ↩ ↩2

-

Ghosh, D., et al. (2024). "18 percent of residues associated with biological processes showed hallucinations." AlphaFold3 IDP Hallucinations Study. bioRxiv. https://doi.org/10.1101/2024.08.05.606142 ↩ ↩2

-

Ghosh, D., et al. (2024). "More than 50% of the proteins had less than 70% alignment with DisProt." AlphaFold3 IDP Hallucinations Study. bioRxiv. https://doi.org/10.1101/2024.08.05.606142 ↩

-

Ghosh, D., et al. (2024). "The pLDDT is a confidence score that indicates the reliability of the structural predictions for each residue, with scores above 70 typically considered to indicate high confidence." AlphaFold3 IDP Hallucinations Study. bioRxiv. https://doi.org/10.1101/2024.08.05.606142 ↩

-

Wang, Z., et al. (2024). BEACON: Benchmark for Comprehensive RNA Tasks and Language Models. NeurIPS 2024 Datasets and Benchmarks Track. ↩

-

Zhang, J., et al. (2024). OmniGenBench: Comprehensive Benchmarking of Genomic Foundation Models. arXiv. https://arxiv.org/abs/2410.01784 ↩

-

Zhang, J., et al. (2024). "In the secondary structure prediction tasks (Archive2, Stralign, bpRNA), OmniGenome demonstrates superior performance." OmniGenBench Genomic Foundation Models. arXiv. https://arxiv.org/abs/2410.01784 ↩

-

Zhang, J., et al. (2024). "Despite decades of advancements in molecular biology, deciphering genomes remains a significant challenge." OmniGenBench Genomic Foundation Models. arXiv. https://arxiv.org/abs/2410.01784 ↩

-

Zhang, J., et al. (2024). "The central dogma of biology posits that genomes, including DNA and RNA, encode and transmit the genetic information essential for all living systems and underpin the translation of proteins." OmniGenBench Genomic Foundation Models. arXiv. https://arxiv.org/abs/2410.01784 ↩

-

Ghosh, D., et al. (2024). "7.6% of the aligned residues were involved in structural transition." AlphaFold3 IDP Hallucinations Study. bioRxiv. https://doi.org/10.1101/2024.08.05.606142 ↩

-

Ghosh, D., et al. (2024). "30% did not show hallucinations at segments known to have a biological context." AlphaFold3 IDP Hallucinations Study. bioRxiv. https://doi.org/10.1101/2024.08.05.606142 ↩

-

Zhang, J., et al. (2024). "GFMs incorporating structural context, like OmniGenome, can generalize effectively across different genomic modalities (RNA and DNA) and species (plants)." OmniGenBench Genomic Foundation Models. arXiv. https://arxiv.org/abs/2410.01784 ↩

-

Zhang, J., et al. (2024). "GB includes 9 datasets focusing on various regulatory elements, such as promoters, enhancers, and open chromatin regions, across different species like humans, mice, and roundworms." OmniGenBench Genomic Foundation Models. arXiv. https://arxiv.org/abs/2410.01784 ↩

-

Ghosh, D., et al. (2024). "8% of the proteins show a higher degree of hallucination (60-80%) at the regions involved in biological processes." AlphaFold3 IDP Hallucinations Study. bioRxiv. https://doi.org/10.1101/2024.08.05.606142 ↩

-

Ghosh, D., et al. (2024). "The number of IDP documented in DisProt is approximately 3000." AlphaFold3 IDP Hallucinations Study. bioRxiv. https://doi.org/10.1101/2024.08.05.606142 ↩

-

Ghosh, D., et al. (2024). "The human proteome has approx 20000 protein-coding genes (based on current UniProt/Ensembl data) in its canonical form." AlphaFold3 IDP Hallucinations Study. bioRxiv. https://doi.org/10.1101/2024.08.05.606142 ↩

-

Ghosh, D., et al. (2024). "Comparison of predictions (ordered/disordered) in the native state with predictions in the context-based state from AF3 revealed that the latter results aligned with the former in 89% of residues." AlphaFold3 IDP Hallucinations Study. bioRxiv. https://doi.org/10.1101/2024.08.05.606142 ↩

-

Ghosh, D., et al. (2024). "18% of the residues involved in the biological processes showed hallucinations." AlphaFold3 IDP Hallucinations Study. bioRxiv. https://doi.org/10.1101/2024.08.05.606142 ↩

-

Ghosh, D., et al. (2024). "The generalizability of the study is constrained by its limited sample size (72 out of 3000+ DisProt proteins)." AlphaFold3 IDP Hallucinations Study. bioRxiv. https://doi.org/10.1101/2024.08.05.606142 ↩