Your Brain on Rhythm: What 39 Cultures Taught Scientists About Universal Music

Everyone claps along to music. At a wedding in Lagos, a concert in Tokyo, a village celebration in the Bolivian Amazon, people find the beat and move to it. But try clapping to a rhythm from a culture you have never encountered. Something feels slightly off, like your hands want to land somewhere else. This gap between what feels natural and what feels foreign raises a question that has occupied scientists for decades: Is our sense of rhythm built into our biology, or does culture shape what sounds right?

A landmark study spanning five continents has finally delivered an answer. It is both.

Researchers tested rhythm perception across 39 participant groups in 15 countries. Source: MIT News, Massachusetts Institute of Technology (2024).

Researchers tested rhythm perception across 39 participant groups in 15 countries. Source: MIT News, Massachusetts Institute of Technology (2024).

Why Did Scientists Need 39 Cultures to Answer This?

The debate over musical universals has simmered for generations. Universalists argue that certain musical features are hardwired into human cognition. Relativists counter that music is entirely learned, varying as dramatically across cultures as language does.

Both camps had evidence. But most music psychology research suffers from a critical flaw: it uses what researchers call "WEIRD participants, that is, individuals who hail from Western, Educated, Industrialized, Rich, and Democratic societies"1. Testing American college students tells us about American college students. It says little about humanity.

Nori Jacoby, a researcher at the Max Planck Institute, and Josh McDermott at MIT decided to test rhythm perception properly. They would go everywhere, from university labs to remote villages, and ask a simple question: When people hear random rhythms and tap them back, what patterns do they gravitate toward?

How Do You Test Rhythm Across Cultures?

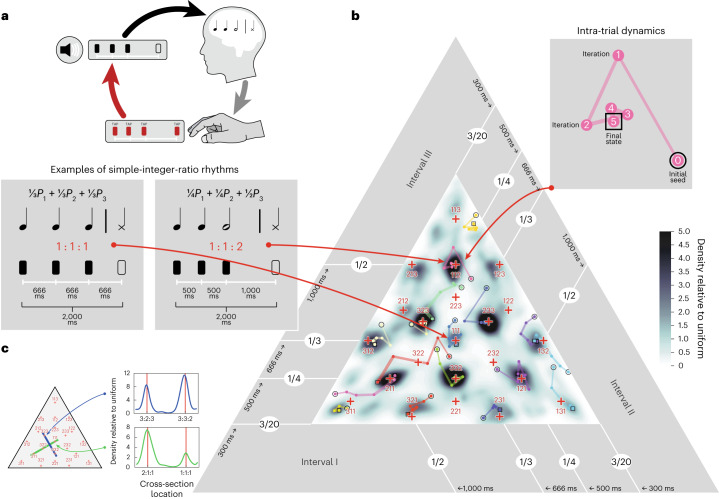

The researchers designed an experiment elegant enough to work anywhere. "Scientists used an iterative task where participants listened to randomly generated beats, then tapped back what they heard. Repeated iterations revealed each listener's internal musical biases or 'priors'"2.

Think of it like the telephone game. A random rhythm plays. You tap it back. Your tapped version plays again. You tap that. After several rounds, the rhythm stops being random and starts converging toward whatever pattern feels most natural to you.

Figure 1: The iterated reproduction paradigm. Participants heard random three-interval rhythms and tapped them back repeatedly, revealing their internal preferences. Source: Jacoby, N., et al. (2024). Nature Human Behaviour.

Figure 1: The iterated reproduction paradigm. Participants heard random three-interval rhythms and tapped them back repeatedly, revealing their internal preferences. Source: Jacoby, N., et al. (2024). Nature Human Behaviour.

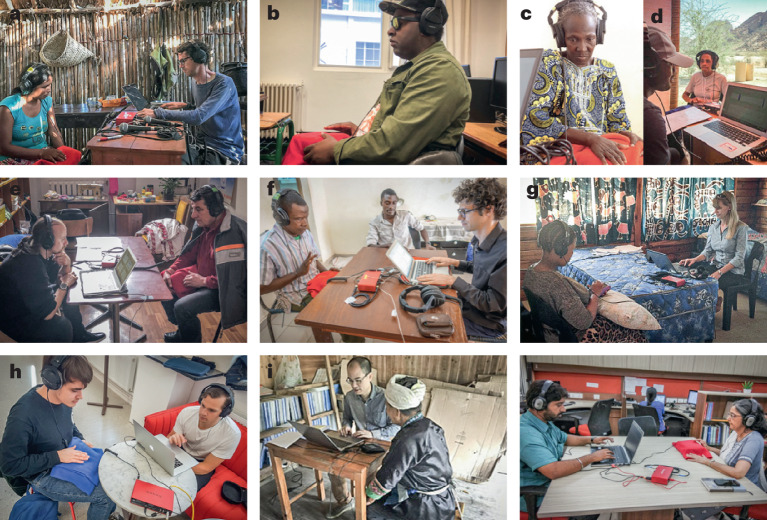

The scale was remarkable. The team tested "923 participants from 39 groups in 15 countries" across "5 continents: North America, South America, Europe, Africa, Asia"3. They did not just visit universities. They worked with Malian drummers, Bulgarian folk musicians, Bolivian villagers, and Botswanan traditional musicians alongside the usual college students.

Figure 2: Global distribution of testing sites. The study brought experiments to villages in Mali, Botswana, and Bolivia, as well as laboratories across North America, Europe, and Asia. Source: Jacoby, N., et al. (2024). Nature Human Behaviour.

Figure 2: Global distribution of testing sites. The study brought experiments to villages in Mali, Botswana, and Bolivia, as well as laboratories across North America, Europe, and Asia. Source: Jacoby, N., et al. (2024). Nature Human Behaviour.

Figure 3: Research participants from diverse settings. The study brought rhythm experiments to traditional villages and modern laboratories alike. Source: Jacoby, N., et al. (2024). Nature Human Behaviour.

Figure 3: Research participants from diverse settings. The study brought rhythm experiments to traditional villages and modern laboratories alike. Source: Jacoby, N., et al. (2024). Nature Human Behaviour.

What Did They Discover?

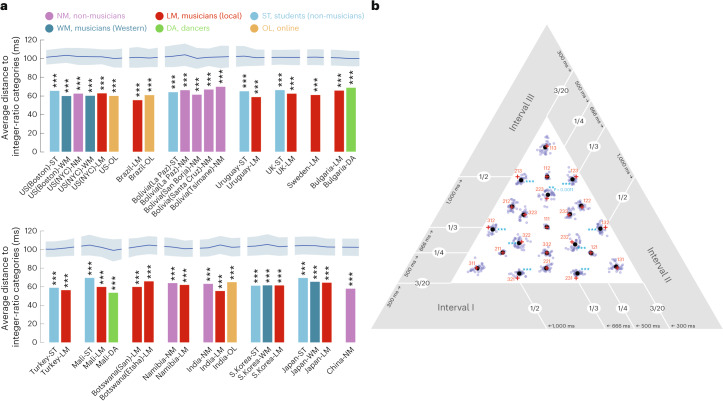

The results revealed something striking. "Every single group exhibits biases for integer ratios...variation that can occur across cultures, which can be quite substantial"4.

Integer ratios are rhythms where the beats relate by simple fractions: 1:1:1 (evenly spaced), 2:1 (long-short), 3:3:2 (the clave rhythm underlying much African and Latin music). When participants tapped back random rhythms, they unconsciously transformed them toward these mathematically simple patterns. It happened in Boston. It happened in Tokyo. It happened in villages without electricity.

"All 39 groups showed probability mass significantly closer to small-integer ratios than chance"5. In plain English: every human group tested, without exception, showed brains that naturally gravitate toward these mathematically simple rhythms.

Figure 4: Relationship between rhythm priors and integer ratios. Every tested group gravitated toward mathematically simple rhythms, suggesting a universal cognitive foundation. Source: Jacoby, N., et al. (2024). Nature Human Behaviour.

Figure 4: Relationship between rhythm priors and integer ratios. Every tested group gravitated toward mathematically simple rhythms, suggesting a universal cognitive foundation. Source: Jacoby, N., et al. (2024). Nature Human Behaviour.

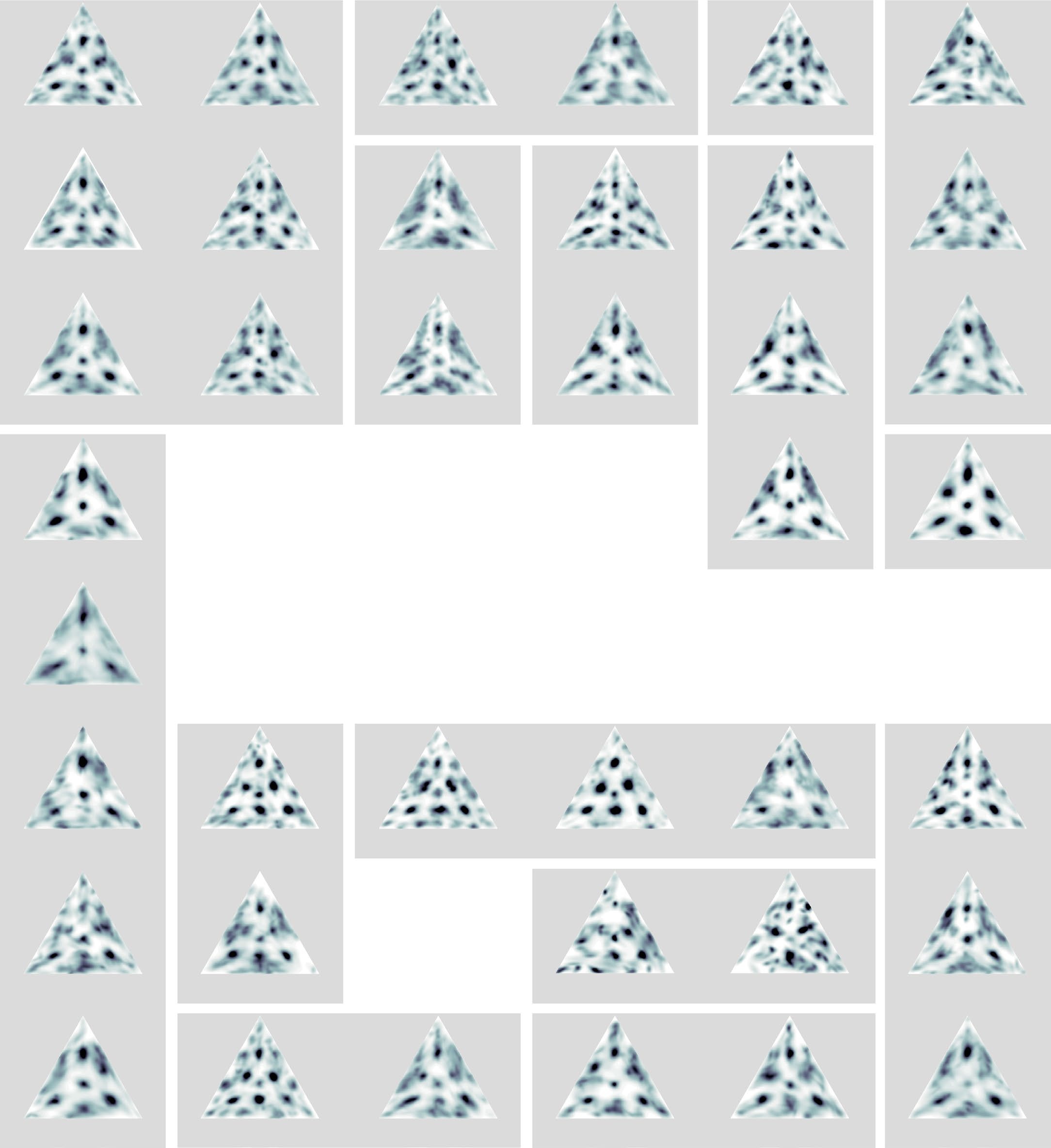

But which integer ratios dominated varied dramatically by culture. "The 2:2:3 rhythm dominated among traditional musicians in Turkey, Botswana, and Bulgaria, while the 3:3:2 pattern appeared strongly in African and Afro-diasporic musical traditions"6. The study even found a "7:2:3 rhythm" that "appeared specifically in Malian drummer groups, linked to the traditional 'Maraka' piece"7.

When the researchers tested "members of the Tsimane tribe in Bolivia, a population with minimal Western music exposure, they found similar underlying bias toward integer ratios. However, the Tsimane preferred different specific ratios, ones that corresponded to their own traditional music rather than Western compositions"8.

Figure 5: Summary of rhythm priors across all 39 groups. Dark spots indicate preferred rhythms. Universal clustering at integer ratio positions, with substantial variation in which ratios each culture favors. Source: Jacoby, N., et al. (2024). Nature Human Behaviour.

Figure 5: Summary of rhythm priors across all 39 groups. Dark spots indicate preferred rhythms. Universal clustering at integer ratio positions, with substantial variation in which ratios each culture favors. Source: Jacoby, N., et al. (2024). Nature Human Behaviour.

Why Does Training Matter Less Than You Think?

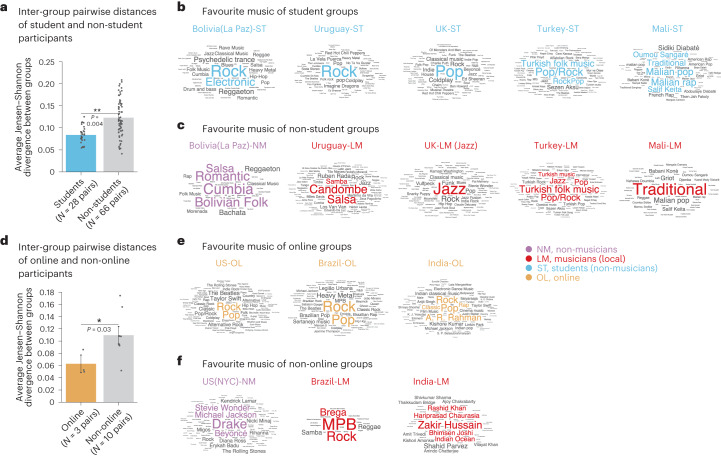

Perhaps the most surprising finding concerned how these preferences develop. Musical training barely matters. "Passive music exposure, rather than formal musical training, shapes rhythmic preferences. Notably, traditional society participants showed markedly different biases than college students and online participants from the same countries"9.

In other words, years of piano lessons matter less than what you heard at family gatherings, on the radio, or at community celebrations. "Rhythm priors were similar for musicians and non-musicians in Boston, USA"10. Professional musicians tap more precisely, but they gravitate toward the same patterns as everyone else who grew up in their culture.

Consider Bulgaria. Bulgarian folk music is famous for its "aksak" rhythms, a Turkish word meaning "limping, stumbling, or slumping" that describes how these uneven beats feel to outsiders11. "Bulgarian folk musicians think of beats as either 'quick' or 'slow', with the 'slow' beat being approximately 1 1/2 times as long as the 'quick'"12. These "uneven rhythms include 5/16, 7/16, 9/16, 11/16, 15/16, 18/16, and 22/16"13. To Bulgarian dancers, these patterns feel as natural as 4/4 time feels to someone raised on rock and pop.

Bulgarian folk dancers demonstrate the rhythmic traditions that shape their community's rhythm preferences. The 2:2:3 "aksak" pattern appeared strongly in Bulgarian participants' tapping experiments. Source: Jacoby, N., et al. (2024). Nature Human Behaviour.

Bulgarian folk dancers demonstrate the rhythmic traditions that shape their community's rhythm preferences. The 2:2:3 "aksak" pattern appeared strongly in Bulgarian participants' tapping experiments. Source: Jacoby, N., et al. (2024). Nature Human Behaviour.

The finding carries a warning for research methods. "The distance between student groups was significantly smaller than that between non-student groups"14. College students worldwide, exposed to similar pop music through streaming services, have converging rhythm preferences. "What's very clear from the paper is that if you just look at the results from undergraduate students around the world, you vastly underestimate the diversity that you see otherwise"15.

Figure 6: Comparing university students to traditional community members. College students from different countries showed more similar rhythm preferences than traditional musicians did, likely due to greater exposure to global popular music. Source: Jacoby, N., et al. (2024). Nature Human Behaviour.

Figure 6: Comparing university students to traditional community members. College students from different countries showed more similar rhythm preferences than traditional musicians did, likely due to greater exposure to global popular music. Source: Jacoby, N., et al. (2024). Nature Human Behaviour.

What Does This Mean for Medicine, Education, and Technology?

The research has practical implications that extend well beyond academic debates.

In medicine, rhythmic therapies are already helping patients with movement disorders. "The inherent periodicity of auditory rhythmic patterns could entrain movement patterns in patients with movement disorders"16. Research shows "RAS is an effective tool to improve spatiotemporal gait parameters, enhancing gait velocity and stride length" in Parkinson's patients17. Understanding how cultural background shapes rhythm perception could help therapists match interventions to patients.

In education, the findings challenge curricula built entirely around Western notation. "Throughout U.S. history there has been a disproportionate over-valuing of Western European music history, theory, and repertoire"18. Knowing that students bring legitimate, culturally-shaped rhythm intuitions to the classroom could transform how we teach music.

In technology, music recommendation algorithms and AI composition tools inherit cultural biases from their training data. "Approximately 86% of dataset hours focus on Global North music"19, while "African music comprises merely 27.50 hours despite a population of 1.22 billion"20. "Current AI music generation systems often default to Western tonal and rhythmic structures when tasked with generating non-Western music"21. Understanding rhythm universals and variations could help build more inclusive music technology.

What Your Rhythm Reveals About You

The brain's preference for integer ratios appears to serve an important function. "The brain's preference appears to function as an error-correction system, allowing societies to maintain consistent musical traditions despite performance imperfections"22. When a drummer rushes or drags, listeners mentally correct the rhythm toward what their culture expects. This keeps musical traditions stable across generations.

Think of it like spell-check for rhythm. Your brain has templates for patterns that "make sense," and it interprets what you hear through those templates. The templates themselves are shaped by what you grew up hearing, but they are always based on simple mathematical ratios.

"Our mental representation is robust to mistakes, but pushes us toward preexisting musical structures"23. Music survives transmission errors because our brains automatically clean up the signal.

The next time you hear music from an unfamiliar tradition, pay attention to how your brain responds to its rhythms. That reaction, a mix of immediate recognition and subtle strangeness, reveals something about both our shared biology and your individual cultural programming. Your hands want to find the beat. They just disagree with hands raised in a different musical tradition about exactly where that beat should fall.

We are all wired the same way. We just got different software loaded.

References

Footnotes

-

Jacoby, N., et al. (2020). Cross-cultural work in music cognition: Challenges, insights, and recommendations. Music Perception, 37(3), 185-195. https://doi.org/10.1525/mp.2020.37.3.185 ↩

-

MIT News. (2024, March 4). Exposure to different kinds of music influences how the brain interprets rhythm. https://news.mit.edu/2024/exposure-different-kinds-music-influences-how-brain-interprets-rhythm-0304 ↩

-

Jacoby, N., et al. (2024). Commonality and variation in mental representations of music revealed by a cross-cultural comparison of rhythm priors in 15 countries. Nature Human Behaviour, 8, 846-877. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-023-01800-9 ↩

-

Jacoby, N., quoted in MIT News. (2024, March 4). https://news.mit.edu/2024/exposure-different-kinds-music-influences-how-brain-interprets-rhythm-0304 ↩

-

Jacoby, N., et al. (2024). Nature Human Behaviour, 8, 846-877. ↩

-

Jacoby, N., et al. (2024). Nature Human Behaviour, 8, 846-877. ↩

-

Jacoby, N., et al. (2024). Nature Human Behaviour, 8, 846-877. ↩

-

MIT News. (2017, December 5). How the brain perceives rhythm. https://news.mit.edu/2017/how-brain-perceives-rhythm-1205 ↩

-

Jacoby, N., et al. (2024). Nature Human Behaviour, 8, 846-877. ↩

-

Jacoby, N., et al. (2024). Nature Human Behaviour, 8, 846-877. ↩

-

Britannica. Aksak. https://www.britannica.com/art/aksak ↩

-

Folkdance Footnotes. Bulgarian Dance Rhythms. https://folkdancefootnotes.org/dance/dance-information/bulgarian-dance-rhythms/ ↩

-

Folkdance Footnotes. Bulgarian Dance Rhythms. https://folkdancefootnotes.org/dance/dance-information/bulgarian-dance-rhythms/ ↩

-

Jacoby, N., et al. (2024). Nature Human Behaviour, 8, 846-877. ↩

-

Jacoby, N., quoted in Max Planck Institute profile. https://news.mit.edu/2024/exposure-different-kinds-music-influences-how-brain-interprets-rhythm-0304 ↩

-

Thaut, M. H., McIntosh, G. C., & Hoemberg, V. (2015). Neurobiological foundations of neurologic music therapy. Frontiers in Psychology, 5, 1185. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2014.01185 ↩

-

Sihvonen, A. J., et al. (2022). Rhythm and music-based interventions in motor rehabilitation. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 15, 789467. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnhum.2021.789467 ↩

-

Culturally Responsive Music Education Research. University of Nevada, Las Vegas. https://oasis.library.unlv.edu/ ↩

-

Missing Melodies: AI Music Generation and Global South Representation. (2024). arXiv. https://arxiv.org/html/2412.04100v3 ↩

-

Missing Melodies: AI Music Generation and Global South Representation. (2024). arXiv. ↩

-

Missing Melodies: AI Music Generation and Global South Representation. (2024). arXiv. ↩

-

Science Daily. (2024, March 4). How musical exposure shapes brain's rhythm perception. https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2024/03/240304135838.htm ↩

-

McDermott, J. H., quoted in MIT News. (2024, March 4). https://news.mit.edu/2024/exposure-different-kinds-music-influences-how-brain-interprets-rhythm-0304 ↩