Why Your LLM Only Uses 10-20% of Its Context Window (And How TITANS Fixes It)

Here's an uncomfortable truth about the 128K context window your favorite LLM advertises: it probably uses about 10-20% of it effectively.1 GPT-4, despite its impressive 128K token limit, effectively utilizes only about 10% of that full window.2 The rest is, functionally, padding.

This isn't a bug in any particular model. It's a limitation of how transformers process sequences. And in January 2025, Google Research published a paper that takes a genuinely different approach to solving it: TITANS, a neural architecture that learns to memorize during inference, not just training.3

Let me walk you through how this actually works.

The Problem: Attention's Quadratic Tax

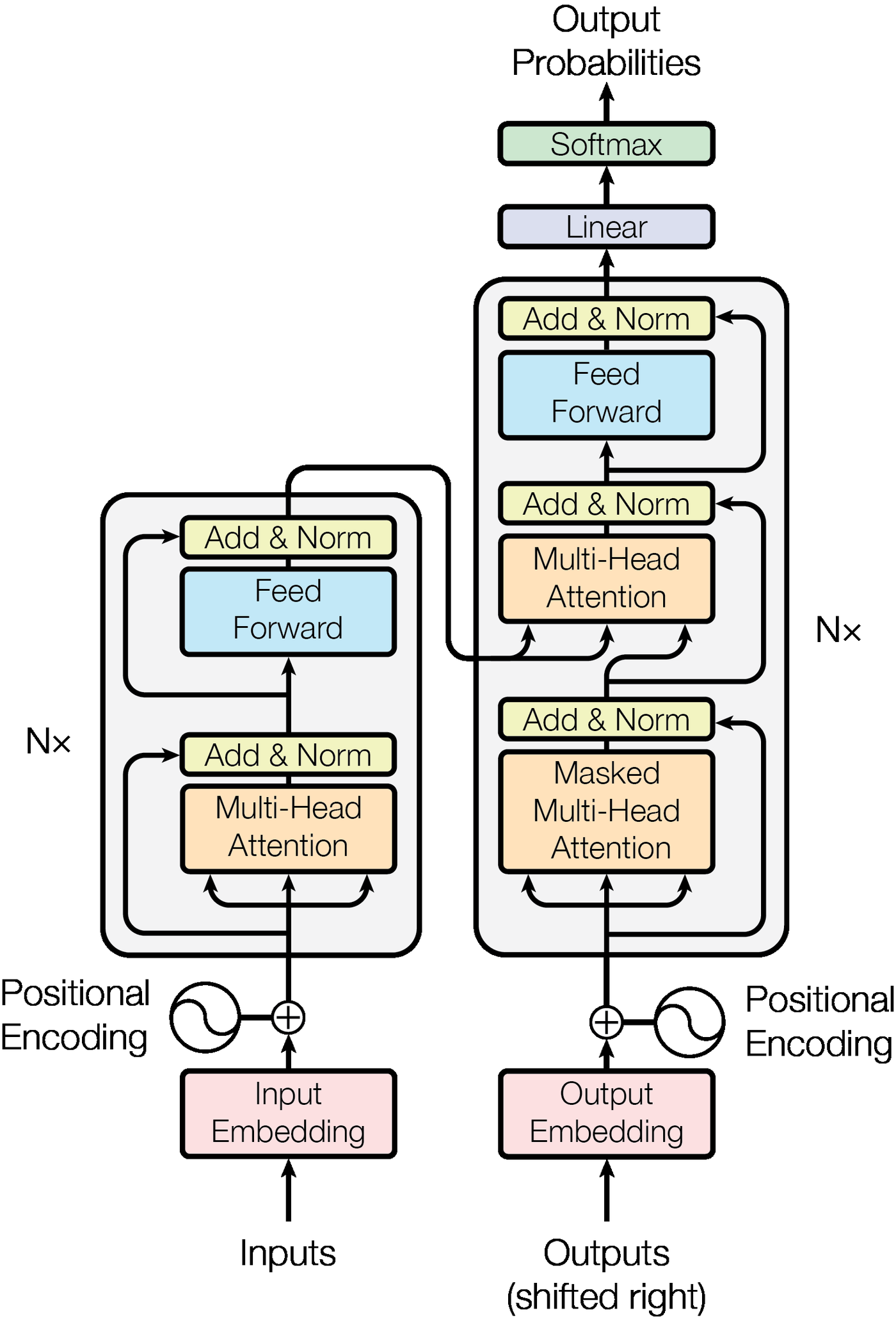

The transformer architecture revolutionized sequence modeling by enabling parallel processing through self-attention.4 But this power comes with a cost: "as the context length increases, LLMs see a linear increase in memory to store the Key-Value (KV) cache and a quadratic increase in time for attention computation."5

Figure 1: The original Transformer architecture from Vaswani et al. Self-attention enables powerful sequence modeling but scales quadratically with context length. Source: Vaswani et al., "Attention Is All You Need" (arXiv:1706.03762)

Figure 1: The original Transformer architecture from Vaswani et al. Self-attention enables powerful sequence modeling but scales quadratically with context length. Source: Vaswani et al., "Attention Is All You Need" (arXiv:1706.03762)

This quadratic scaling is why extending context windows has been such an engineering challenge. Double your context, quadruple your compute. At some point, the math stops working in your favor.

But there's a deeper problem beyond raw compute. The BABILong benchmark, which tests reasoning across extremely long documents, revealed something troubling: "popular LLMs effectively utilize only 10-20% of the context and their performance declines sharply with increased reasoning complexity."6 Only 23 out of 34 tested LLMs could correctly answer 85% or more of questions for basic reasoning tasks, even without any distractor text.7

The fundamental tension is this: "Attention is both effective and inefficient because it explicitly does not compress context at all."8 Meanwhile, "recurrent models are efficient because they have a finite state, implying constant-time inference and linear-time training. However, their effectiveness is limited by how well this state has compressed the context."9

What if we could get both?

A Different Way to Think About Memory

Your brain doesn't re-read an entire book every time you want to recall a character's name. Neither should AI.

The TITANS paper starts from this premise: what if we designed neural architectures the way human memory actually works? "Memory is a confederation of systems, e.g., short-term, working, and long-term memory, each serving a different function with different neural structures, and each capable of operating independently."10

Current transformers, the TITANS authors argue, work like short-term memory only. "From a memory perspective, we argue that attention due to its limited context but accurate dependency modeling performs as a short-term memory, while neural memory due to its ability to memorize the data, acts as a long-term, more persistent, memory."11

The key insight is that attention excels at precise, local reasoning but struggles with information that appeared thousands of tokens ago. What if we could add a complementary system optimized for long-term storage?

How TITANS Actually Works

TITANS introduces something genuinely novel: a neural network that updates its own parameters during inference. "We present a (deep) neural long-term memory that (as a meta in-context model) learns how to memorize/store the data into its parameters at test time."12

Think about what this means. Traditional transformers have fixed weights after training. They can't learn new information without retraining or fine-tuning. TITANS breaks this barrier by introducing a memory module that treats the context window as a continuous learning opportunity.

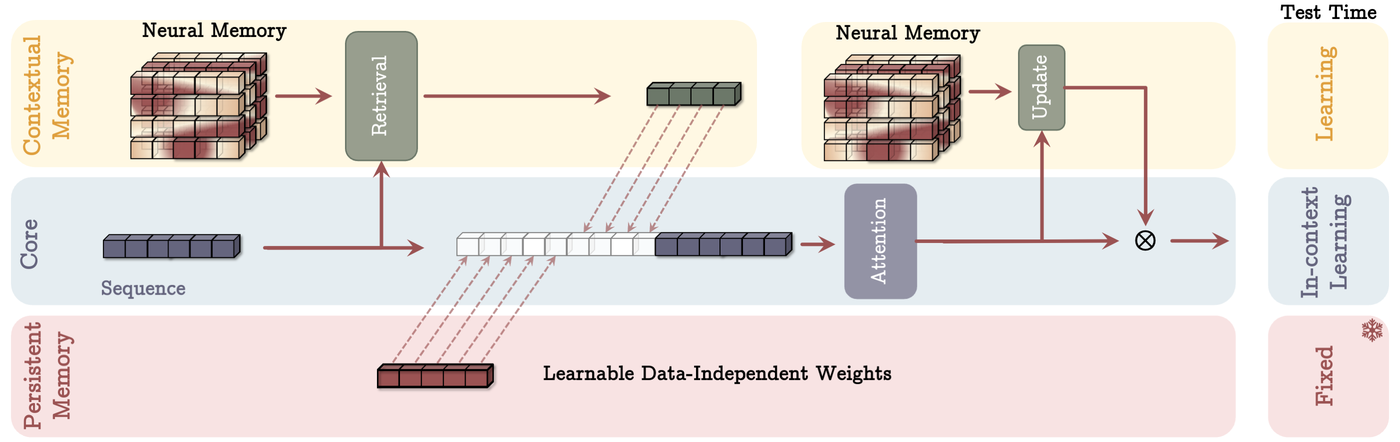

Figure 2: TITANS architecture showing three memory layers: Contextual Memory (learning at test time), Core (in-context learning via attention), and Persistent Memory (fixed learnable weights). Source: Behrouz et al., "TITANS: Learning to Memorize at Test Time" (arXiv:2501.00663)

Figure 2: TITANS architecture showing three memory layers: Contextual Memory (learning at test time), Core (in-context learning via attention), and Persistent Memory (fixed learnable weights). Source: Behrouz et al., "TITANS: Learning to Memorize at Test Time" (arXiv:2501.00663)

The architecture consists of three components working in concert:13

Core (Short-term Memory): Standard attention with a limited window size. It handles the immediate, precise modeling of local dependencies that transformers excel at.

Long-term Memory: This is the key innovation. A neural memory module that actively updates its parameters as data streams through. It doesn't just store information; it learns what to store and when.

Persistent Memory: A set of learnable but data-independent parameters that encode task knowledge. Think of this as procedural memory, the kind that lets you ride a bike without conscious thought.

The Surprise Mechanism: Deciding What to Remember

Here's where TITANS gets particularly interesting. How does the memory module decide what to remember?

"Inspired by human long-term memory system, we design this memory module so an event that violates the expectations (being surprising) is more memorable."14

The implementation is elegant: "We measure the surprise of an input with the gradient of the neural network with respect to the input in associative memory loss."15

Consider a concrete example. When reading a document about cats, the word "cat" is expected and produces a small gradient. The system doesn't need to specially remember it. But if the word "banana" appears unexpectedly, that produces a large gradient. The system recognizes this as surprising information and allocates memory resources accordingly.

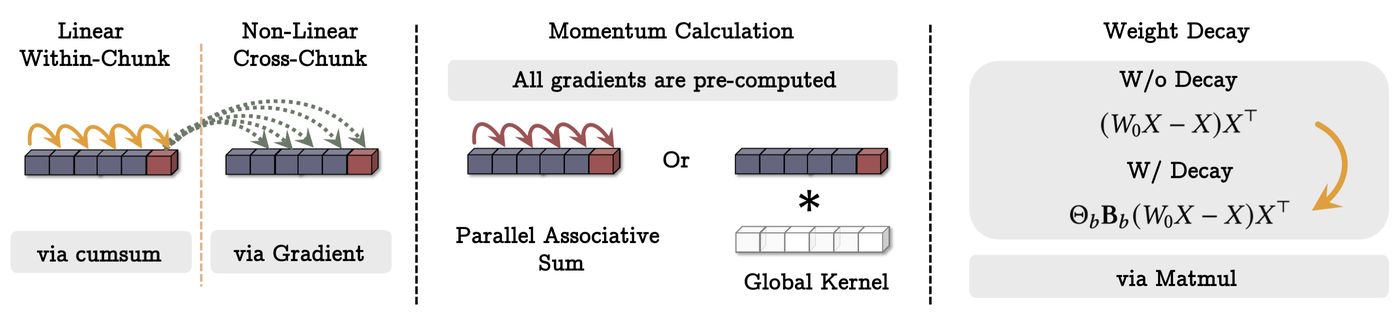

Figure 3: TITANS memory computation showing Linear Within-Chunk processing, Non-Linear Cross-Chunk updates via gradients, Momentum calculation, and Weight Decay mechanisms. Source: Behrouz et al., "TITANS: Learning to Memorize at Test Time" (arXiv:2501.00663)

Figure 3: TITANS memory computation showing Linear Within-Chunk processing, Non-Linear Cross-Chunk updates via gradients, Momentum calculation, and Weight Decay mechanisms. Source: Behrouz et al., "TITANS: Learning to Memorize at Test Time" (arXiv:2501.00663)

"Interestingly, we find that this mechanism is equivalent to optimizing a meta neural network with mini-batch gradient descent, momentum, and weight decay."16 The momentum term "acts as a memory of surprise across time (sequence length)."17 Consecutive surprising tokens reinforce each other, creating stronger memory traces.

But memory without forgetting is just hoarding. TITANS addresses this through adaptive weight decay: "We show that this decay mechanism is in fact the generalization of forgetting mechanism in modern recurrent models."18

Three Ways to Add Memory

The paper presents three architectural variants for integrating memory:19

- MAC (Memory as Context): Memory outputs are prepended to the context window

- MAG (Memory as Gate): Memory modulates attention through gating

- MAL (Memory as Layer): Memory operates as a separate processing layer

Each variant has different tradeoffs. MAC is most similar to standard transformer workflows and easiest to integrate. MAG provides fine-grained control over how memory influences attention. MAL offers the cleanest separation of concerns but requires more architectural changes.

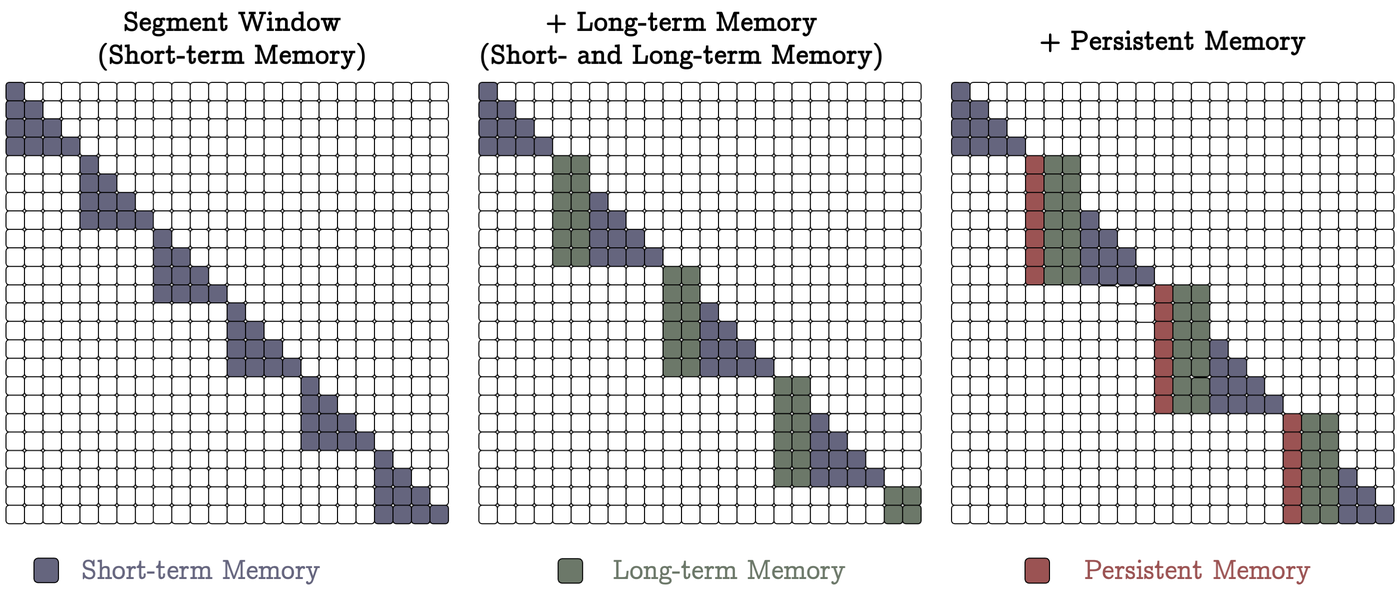

Figure 4: Attention pattern visualization showing how different memory types contribute. Short-term memory alone (left), with Long-term Memory added (center), and with Persistent Memory (right). Source: Behrouz et al., "TITANS: Learning to Memorize at Test Time" (arXiv:2501.00663)

Figure 4: Attention pattern visualization showing how different memory types contribute. Short-term memory alone (left), with Long-term Memory added (center), and with Persistent Memory (right). Source: Behrouz et al., "TITANS: Learning to Memorize at Test Time" (arXiv:2501.00663)

What's notable is that all three variants outperform existing approaches. "Comparing the hybrid models, we found that all three variants of Titans (MAC, MAG, and MAL) outperform both Samba (Mamba + attention) and GatedDeltaNet-H2 (GatedDeltaNet + attention)."20

The Benchmark Results

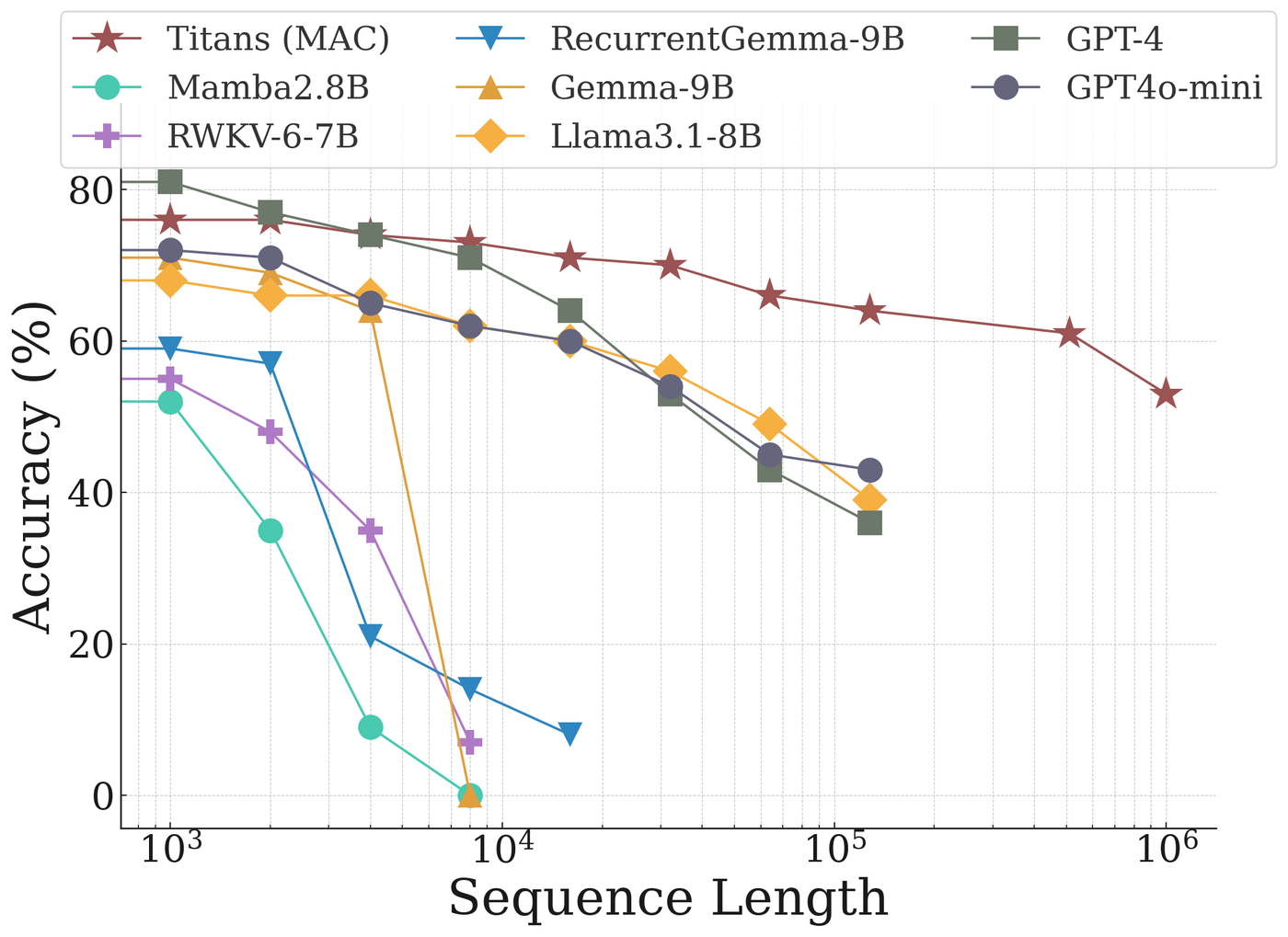

Now for the numbers that matter. On the BABILong benchmark, "Titans outperform all models even extremely large models like GPT4."21

Figure 5: BABILong benchmark results showing accuracy vs sequence length. TITANS maintains high accuracy at lengths where other models degrade significantly. Source: Behrouz et al., "TITANS: Learning to Memorize at Test Time" (arXiv:2501.00663)

Figure 5: BABILong benchmark results showing accuracy vs sequence length. TITANS maintains high accuracy at lengths where other models degrade significantly. Source: Behrouz et al., "TITANS: Learning to Memorize at Test Time" (arXiv:2501.00663)

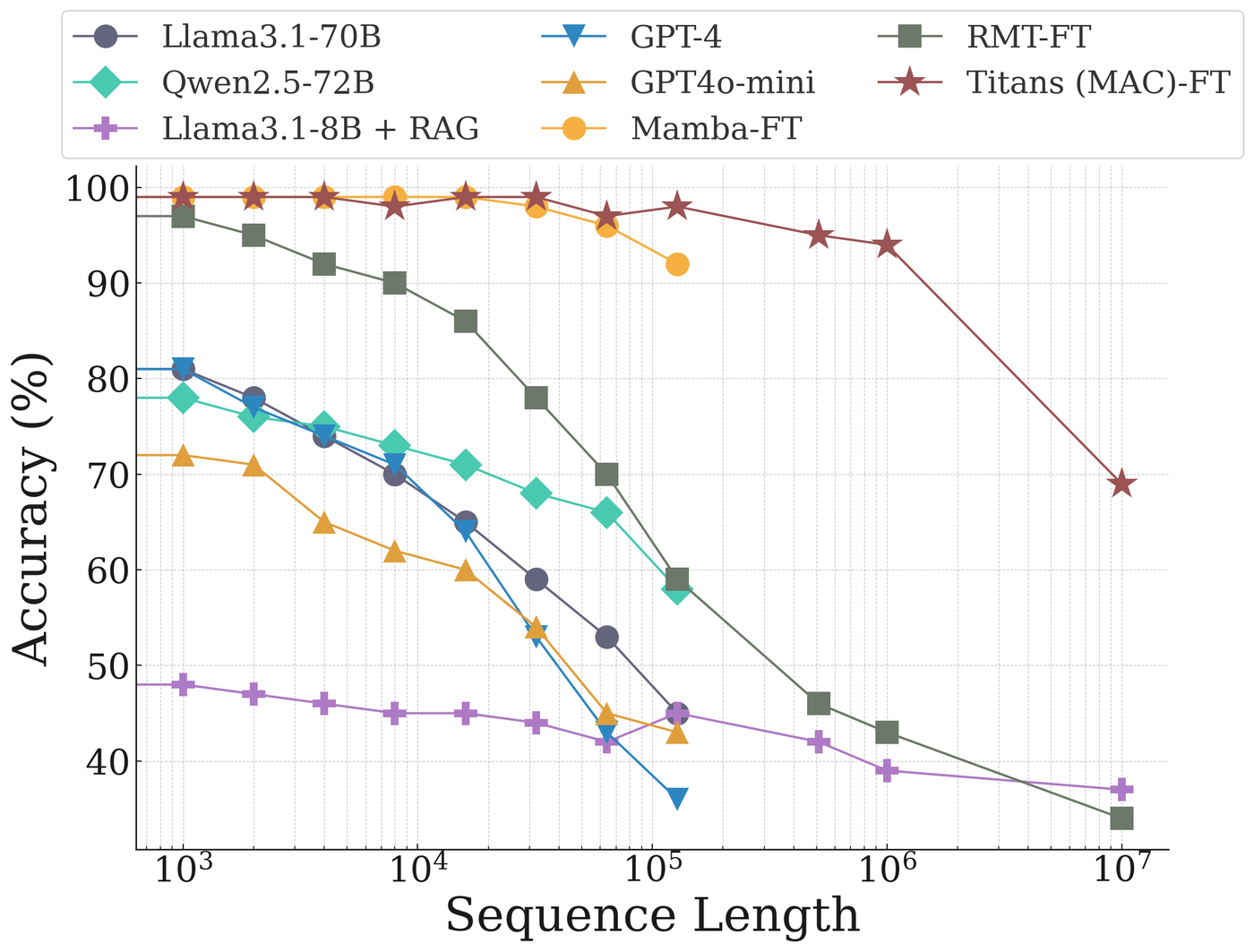

The architecture scales effectively. While standard transformers hit computational walls, TITANS models "can effectively scale to larger than 2M context window size with higher accuracy in needle-in-haystack tasks compared to baselines."22

Here's a striking comparison: "Even augmenting Llama3.1-8B model with RAG performs worse than Titans with about x70 less parameters."23 A smaller model with better memory architecture beats a much larger model using retrieval augmentation.

Figure 6: Extended benchmark showing accuracy up to 10 million tokens. TITANS (fine-tuned) maintains performance at scales where other approaches fail. Source: Behrouz et al., "TITANS: Learning to Memorize at Test Time" (arXiv:2501.00663)

Figure 6: Extended benchmark showing accuracy up to 10 million tokens. TITANS (fine-tuned) maintains performance at scales where other approaches fail. Source: Behrouz et al., "TITANS: Learning to Memorize at Test Time" (arXiv:2501.00663)

The theoretical properties are noteworthy too. "Contrary to Transformers, diagonal linear recurrent models, and DeltaNet, all of which are limited to TC0, Titans are capable of solving problems beyond TC0, meaning that Titans are theoretically more expressive than Transformers and most modern linear recurrent models in state tracking tasks."24

MIRAS: The Theoretical Framework

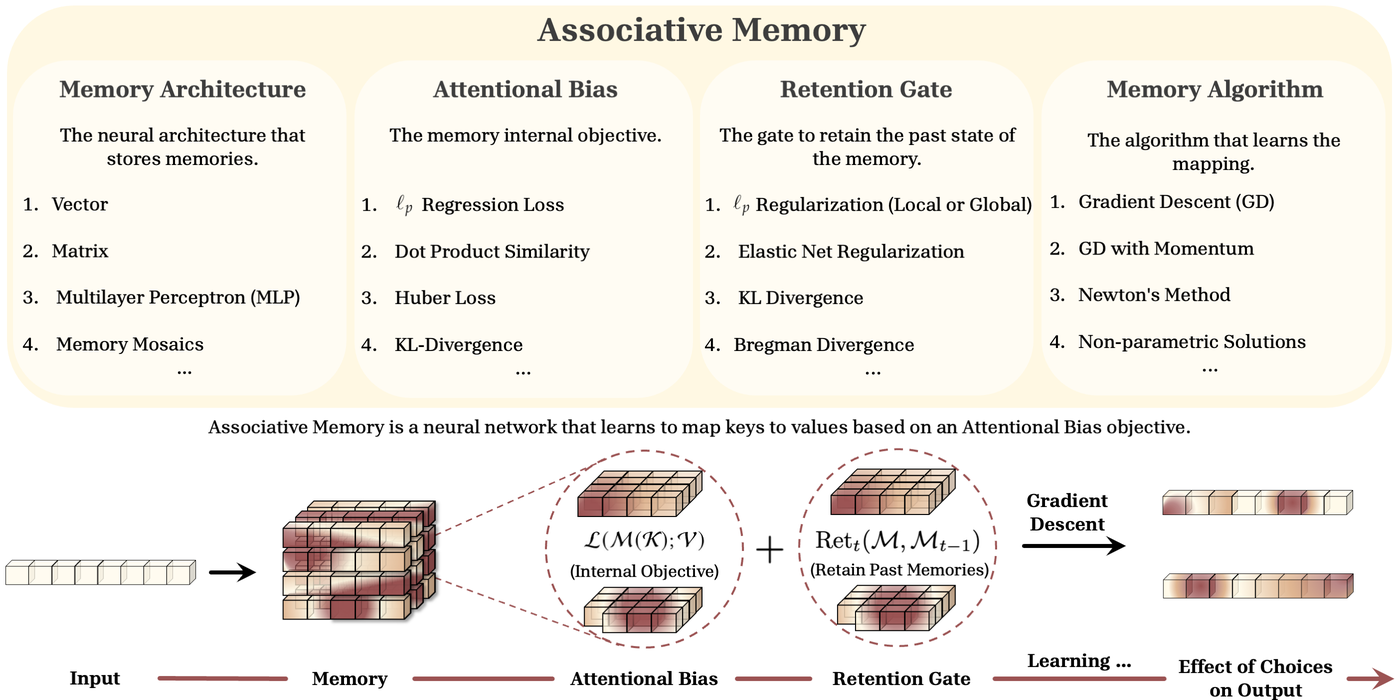

TITANS didn't emerge from a vacuum. It's grounded in a broader theoretical framework called MIRAS, which reconceptualizes neural architectures as associative memory systems.25

The key insight: "Surprisingly, we observed that most existing sequence models leverage either (1) dot-product similarity, or (2) l2 regression objectives as their attentional bias."26 Despite their apparent differences, transformers, RNNs, and state space models share underlying memory mechanisms.

Figure 7: MIRAS Associative Memory framework showing four key components: Memory Architecture, Attentional Bias, Retention Gate, and Memory Algorithm. Source: Behrouz et al., "MIRAS" (arXiv:2504.13173)

Figure 7: MIRAS Associative Memory framework showing four key components: Memory Architecture, Attentional Bias, Retention Gate, and Memory Algorithm. Source: Behrouz et al., "MIRAS" (arXiv:2504.13173)

MIRAS defines sequence models through four choices:27

- Memory Architecture: How information is stored (vector, matrix, MLP, etc.)

- Attentional Bias: What objective guides memory updates

- Retention Gate: How forgetting is managed

- Memory Learning Algorithm: How parameters update

This framework yielded three novel architectures (Moneta, Yaad, and Memora) that "go beyond the power of existing linear RNNs while maintaining a fast parallelizable training process."28

One subtle but important distinction: "The retention gate (forget gate) in Titans is different from Mamba2 and GatedDeltaNet. The main difference comes from the case of full memory erase. While Mamba2 gating removes the entire memory and treats the next token as the first ever seen data, Titans uses a cold start strategy and uses the previous state of the memory to measure the surprise of the incoming token before fully erasing the memory."29

Where This Fits Among Alternatives

TITANS enters a crowded field of approaches to efficient sequence modeling.

Mamba pioneered selective state spaces, achieving linear-time complexity while "matching Transformers of the same size and even matching Transformers twice its size" on language modeling.30 It offers "fast inference (5x higher throughput than Transformers) and linear scaling in sequence length."31 Mamba was "the first linear-time sequence model that truly achieves Transformer-quality performance."32

RWKV combines efficient transformer training with efficient RNN inference through linear attention, scaling to "14 billion parameters, by far the largest dense RNN ever trained."33 RWKV "performs on par with similarly sized Transformers" while offering O(Td) time and O(d) space complexity.34

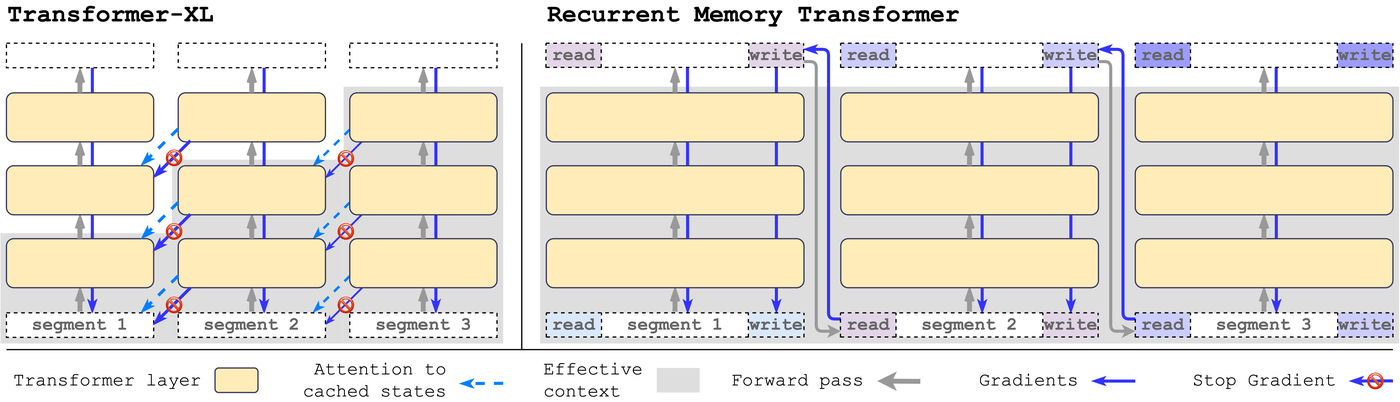

Recurrent Memory Transformer (RMT) showed that memory tokens could enable transformers to handle extremely long contexts, with "memory tokens summarizing and propagating segment information" across up to 2 million tokens.35

Figure 8: Comparison of Transformer-XL (cached states with stop gradients) vs Recurrent Memory Transformer (explicit read/write memory tokens). Source: Bulatov et al., "Recurrent Memory Transformer" (arXiv:2207.06881)

Figure 8: Comparison of Transformer-XL (cached states with stop gradients) vs Recurrent Memory Transformer (explicit read/write memory tokens). Source: Bulatov et al., "Recurrent Memory Transformer" (arXiv:2207.06881)

ARMT pushed further, achieving "79.9% accuracy on BABILong multi-task long-context benchmark by answering single-fact questions over 50 million tokens."36 What's striking: "being trained on 16k tokens only, it strongly performs up to 50 million tokens."37

What distinguishes TITANS is the combination of adaptive memory updates, surprise-based learning, and the ability to actually utilize extended contexts rather than just technically support them.

When to Use TITANS

TITANS is not universally optimal. The architecture shines when:

Long-context is essential. If your application genuinely needs to reason over hundreds of thousands or millions of tokens, TITANS offers capabilities that standard transformers cannot match.

Accuracy on recall tasks is critical. The needle-in-haystack performance suggests TITANS is particularly strong when specific information must be retrieved from long contexts.

Inference efficiency matters. The linear scaling of memory operations means TITANS can be more practical than attention-heavy models at scale.

The architecture may be overkill when:

Short contexts suffice. Standard transformers with FlashAttention optimizations remain highly efficient for contexts under 32K tokens.

RAG is acceptable. For many applications, retrieval-augmented generation provides good enough performance at lower cost, though notably, TITANS outperforms RAG even with models 70x larger.

Here's a simplified implementation demonstrating the core TITANS memory update mechanism:

import torch

import torch.nn as nn

class TitansNeuralMemory(nn.Module):

"""

Neural long-term memory that learns to memorize at test time.

Key insight: Events that violate expectations (high gradient = surprise)

are more memorable, similar to human long-term memory.

"""

def __init__(self, dim: int = 64):

super().__init__()

self.memory = nn.Linear(dim, dim, bias=False)

self.W_k = nn.Linear(dim, dim, bias=False)

self.W_v = nn.Linear(dim, dim, bias=False)

self.W_q = nn.Linear(dim, dim, bias=False)

self.momentum = None

def compute_surprise(self, x: torch.Tensor) -> torch.Tensor:

"""Compute surprise as gradient of associative memory loss."""

k, v = self.W_k(x), self.W_v(x)

predicted = self.memory(k)

loss = ((predicted - v) ** 2).sum()

loss.backward(retain_graph=True)

surprise = self.memory.weight.grad.clone()

self.memory.weight.grad = None

return surprise

def forward(self, x: torch.Tensor,

theta: float = 0.1, # Momentary surprise weight

eta: float = 0.9, # Momentum decay

alpha: float = 0.01): # Forgetting rate

"""

TITANS forward pass with surprise-based memory updates.

Update equations:

S_t = eta * S_{t-1} - theta * grad(loss) # Momentum

M_t = (1 - alpha) * M_{t-1} + S_t # Memory + decay

"""

if self.momentum is None:

self.momentum = torch.zeros_like(self.memory.weight)

# Compute and accumulate surprise

momentary_surprise = self.compute_surprise(x)

self.momentum = eta * self.momentum - theta * momentary_surprise

# Update memory with forgetting

with torch.no_grad():

self.memory.weight.data = (1 - alpha) * self.memory.weight.data + self.momentum

return self.memory(self.W_q(x))

The key insight here is how surprise (gradient magnitude) determines what gets remembered. Larger gradients indicate the memory's prediction was wrong, so the input is "surprising" and worth storing.

The Deeper Pattern

If you zoom out, there's a pattern emerging across all these architectures: the realization that sequence modeling is a memory management problem.

The original RNNs understood this but couldn't scale. "A fundamental problem of sequence modeling is compressing context into a smaller state."38 Transformers solved scaling through parallelization but created new problems through their refusal to compress.

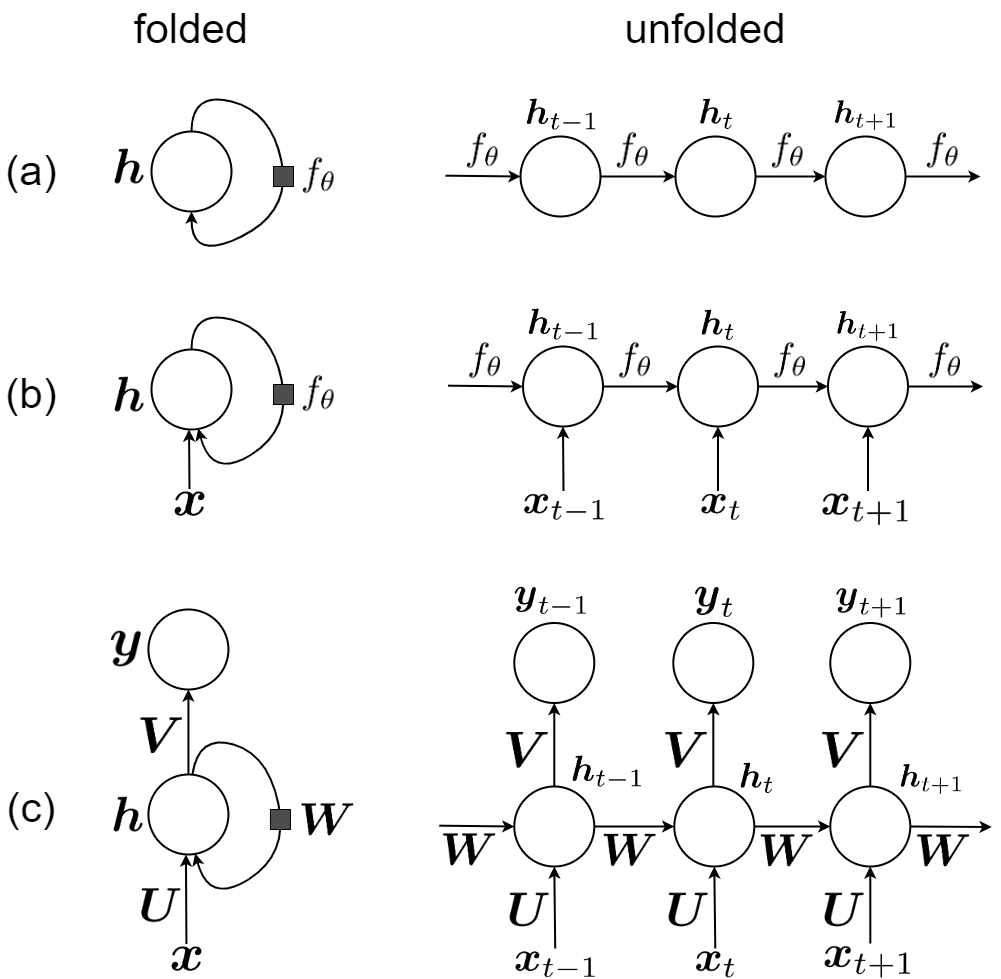

Figure 9: RNN architecture showing folded and unfolded representations. RNNs pioneered sequential memory but suffered from vanishing gradients and limited long-range dependencies. Source: Lindemann et al. (arXiv:2304.11461)

Figure 9: RNN architecture showing folded and unfolded representations. RNNs pioneered sequential memory but suffered from vanishing gradients and limited long-range dependencies. Source: Lindemann et al. (arXiv:2304.11461)

Modern approaches like TITANS, Mamba, and RWKV represent a convergence: architectures that can train like transformers (parallelizable, scalable) while inferencing like RNNs (efficient, constant memory per step). The key differentiator is how they manage the tradeoff between compression and accuracy.

The TITANS training details matter for reproducibility: models were "trained on 15B tokens sampled from FineWeb-Edu dataset" with larger variants using "760M parameters trained on 30B tokens from the same dataset."39

Looking Forward

The TITANS paper raises a theoretical question worth considering: if we can design neural networks that explicitly separate short-term and long-term memory, what other cognitive structures might be worth encoding architecturally?

The move from monolithic attention to differentiated memory systems mirrors how human cognition actually works. We don't process every stimulus identically. We filter, prioritize, and store based on relevance and surprise. TITANS takes a step toward building machines that do the same.

Whether TITANS specifically becomes the dominant approach or simply influences the next generation of architectures, the direction seems clear. The question is no longer how to build bigger context windows. It's how to build smarter memory.

That's not just a larger context window. That's a step toward AI that actually remembers.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the main problem TITANS solves?

TITANS addresses the "lost in the middle" problem where LLMs like GPT-4 only effectively use 10-20% of their advertised context window. While models may technically accept 128K tokens, they struggle to retrieve and reason over information in the middle of long contexts. TITANS introduces test-time memory learning that enables genuine long-context understanding.

How does TITANS differ from simply increasing context window size?

Increasing context window size hits two walls: quadratic compute costs (double context = 4x compute) and degraded recall accuracy. TITANS takes a fundamentally different approach by adding a neural memory module that learns during inference. This memory module decides what to store based on "surprise" (unexpected information), similar to human memory formation.

What is the "surprise" mechanism in TITANS?

TITANS measures surprise using the gradient of its prediction error. When the memory module encounters expected content, the gradient is small. When content is unexpected (high prediction error), the gradient is large. Larger gradients trigger stronger memory storage. This mirrors how human brains preferentially remember surprising or novel experiences.

How does TITANS compare to RAG (Retrieval-Augmented Generation)?

TITANS with ~114M parameters outperforms Llama 3.1-8B augmented with RAG on long-context benchmarks. RAG requires external infrastructure, introduces retrieval latency, and can miss relevant context if the retrieval step fails. TITANS handles long context natively without external systems, making it simpler to deploy and more reliable for tasks requiring comprehensive context understanding.

Can I use TITANS today?

As of January 2025, TITANS is a research architecture from Google without official production releases. However, the paper provides detailed implementation specifications, and community implementations are emerging. The MIRAS framework behind TITANS also produced architectures (Moneta, Yaad, Memora) that may see broader adoption.

What are the three memory types in TITANS?

TITANS uses three complementary memory systems: (1) Core - standard attention for short-term, precise local reasoning; (2) Long-term Memory - a neural module that updates its weights during inference based on surprise; (3) Persistent Memory - fixed learned parameters encoding task knowledge, similar to procedural memory. This mirrors cognitive science models of human memory.

When should I NOT use TITANS?

TITANS may be overkill when: your context fits within 32K tokens (standard transformers with FlashAttention work well); you can tolerate RAG's limitations for your use case; or you need maximum inference speed on short inputs. TITANS shines specifically for applications requiring reasoning over hundreds of thousands to millions of tokens with high recall accuracy.

References

Footnotes

-

Kuratov et al., "BABILong: Testing the Limits of LLMs with Long Context Reasoning-in-a-Haystack," NeurIPS 2024. arXiv:2406.10149 ↩

-

Ibid., line 61 ↩

-

Behrouz et al., "TITANS: Learning to Memorize at Test Time," arXiv:2501.00663, January 2025 ↩

-

Vaswani et al., "Attention Is All You Need," NeurIPS 2017. arXiv:1706.03762 ↩

-

Behrouz et al., TITANS, lines 35-37 ↩

-

Kuratov et al., BABILong, lines 23-25 ↩

-

Ibid., lines 225-227 ↩

-

Dao & Gu, "Mamba: Linear-Time Sequence Modeling with Selective State Spaces," arXiv:2312.00752, lines 208-211 ↩

-

Ibid., lines 211-213 ↩

-

Behrouz et al., TITANS, lines 93-94 ↩

-

Ibid., lines 17-20 ↩

-

Ibid., lines 104-105 ↩

-

Ibid., lines 121-124 ↩

-

Ibid., lines 105-106 ↩

-

Ibid., lines 111-112 ↩

-

Ibid., lines 115-117 ↩

-

Ibid., line 291 ↩

-

Ibid., lines 114-115 ↩

-

Ibid., lines 124-125 ↩

-

Ibid., lines 649-651 ↩

-

Ibid., lines 757-758 ↩

-

Ibid., lines 23-25 ↩

-

Ibid., line 778 ↩

-

Ibid., lines 598-603 ↩

-

Behrouz et al., "MIRAS: A Unified Framework for Memory-based Inductive Reasoning for Sequence Modeling," arXiv:2504.13173 ↩

-

Ibid., lines 17-19 ↩

-

Ibid., lines 22-24 ↩

-

Ibid., lines 24-25 ↩

-

Ibid., lines 536-538 ↩

-

Dao & Gu, Mamba, lines 25-27 ↩

-

Ibid., lines 22-24 ↩

-

Ibid., lines 92-93 ↩

-

Peng et al., "RWKV: Reinventing RNNs for the Transformer Era," EMNLP 2023. arXiv:2305.13048, lines 50-52 ↩

-

Ibid., line 97 ↩

-

Bulatov et al., "Recurrent Memory Transformer," NeurIPS 2022. arXiv:2207.06881 ↩

-

ARMT Authors, "Associative Recurrent Memory Transformer," arXiv:2407.04841, lines 18-21 ↩

-

Ibid., lines 173-174 ↩

-

Dao & Gu, Mamba, line 207 ↩

-

Behrouz et al., TITANS, lines 624-625 ↩