Socrates claimed to know nothing. Modern prompt engineers claim to know exactly what to tell a language model. Both get surprisingly good results, and I think the reason is the same.

I've spent the past year testing a set of prompting techniques that are, give or take some compute, 2,400 years old. The six methods Socrates used in the agora of Athens map onto the most effective prompting strategies we've developed for LLMs 1: definition, elenchus, dialectic, maieutics, generalization, and counterfactual reasoning. Each one corresponds to a specific technique that the research literature has been formalizing independently, often without acknowledging the philosophical lineage. This is not a cute analogy. It is a structural correspondence with measurable performance implications. And it forced me to rethink what "reasoning" in a language model actually means.

Figure 1: A statue of Socrates. His insistence that he knew nothing turned out to be a better epistemic strategy than the Sophists' confident declarations. Source: extracted from Jung et al., "Maieutic Prompting" (2022) 2

Figure 1: A statue of Socrates. His insistence that he knew nothing turned out to be a better epistemic strategy than the Sophists' confident declarations. Source: extracted from Jung et al., "Maieutic Prompting" (2022) 2

There is a reason I am not titling this post "What Ancient Greeks Can Teach Us About AI" and calling it a day. The connection is more precise than that. Edward Chang's 2023 paper systematically mapped Socratic dialogue techniques onto LLM prompting, identifying six methods directly applicable to prompt template engineering and connecting them to "inductive, deductive, and abductive reasoning" 3. Chang also makes a provocative observation about why the Socratic method might be better suited to LLMs than to humans: "when the expert partner is a language model, a machine without emotion or authority, the Socratic method can be effectively employed without the issues that may arise in human interactions" 4. No ego. No defensiveness. No power dynamics. Just questions and answers.

What follows is a practical guide grounded in actual results. I am not going to pretend this is a rigorous benchmark. It's something more useful: a framework for thinking about why certain prompts work, drawn from the oldest tradition of structured inquiry we have.

The Ignorance Advantage

Here's the paradox that started this for me. Standard explanation-based prompting, where you ask an LLM to explain its reasoning, has an error rate of 47% on simple math problems 5. Nearly half the time, asking the model to "show its work" produces wrong answers. Meanwhile, Socrates built an entire philosophical tradition on the premise that the teacher should know less than the student, or at least pretend to. His friend Chaerephon asked the Oracle at Delphi who was the wisest person in Greece, and the Oracle said Socrates 6. Socrates responded by spending the rest of his life trying to prove the Oracle wrong, questioning everyone he met, and discovering that his only advantage was knowing that he didn't know.

This turns out to be a productive stance for prompting LLMs. The Socratic method is "a form of cooperative dialogue whereby participants make assertions about a particular topic, investigate those assertions with questions designed to uncover presuppositions and stimulate critical thinking, and finally come to mutual agreement and understanding" 7. Replace "participants" with "user and model," and you have described the most effective prompting pattern I have found. When you prompt a model as if you already know the answer, you get confirmation. When you prompt it as if you genuinely don't know, through structured questioning rather than instructions, you get reasoning.

Six Ancient Methods, Six Modern Techniques

Figure 2: Chang's mapping of six Socratic questioning strategies to LLM prompting. Each classical technique addresses a specific reasoning failure mode. Source: Chang, "Prompting Large Language Models with the Socratic Method" (2023) 1

Figure 2: Chang's mapping of six Socratic questioning strategies to LLM prompting. Each classical technique addresses a specific reasoning failure mode. Source: Chang, "Prompting Large Language Models with the Socratic Method" (2023) 1

Let me walk through each one with what I have found in practice, showing where the parallels hold, where they break, and where the modern version actually improves on the ancient one.

1. Definition: "What do you mean by that?"

Socrates was famous for asking people to define their terms. He would ask a general what courage meant, or a priest what piety was, and then show them their definition did not hold up. He used definition to "clarify and explain the meaning of key terms and concepts" 8, and in doing so exposed how little his conversation partners actually understood the words they were using.

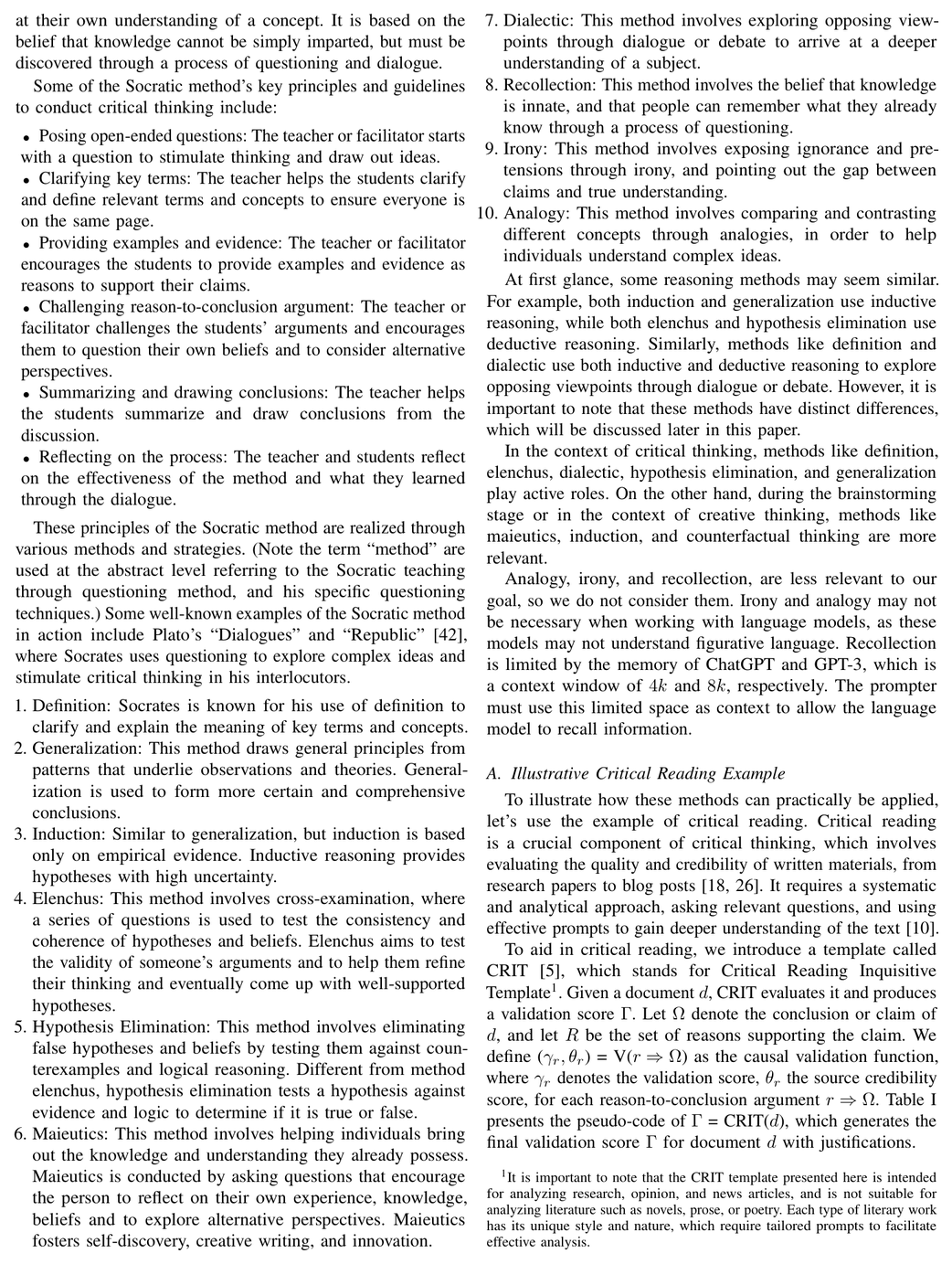

The Rephrase and Respond (RaR) technique does exactly this. You tell the model: "Rephrase and expand the question, then respond." That's it. Across ten different task types, RaR "consistently yields distinguishable improvements for GPT-4" 9. The researchers found that "as opposed to questions asked casually by human, the automatically rephrased questions tend to enhance semantic clarity and aid in resolving inherent ambiguity" 10. Better still, RaR "is complementary to CoT and can be combined with CoT to achieve even better performance" 11.

Figure 3: RaR dramatically improves performance across nine benchmark tasks, especially those requiring careful reasoning. Source: Deng et al., "Rephrase and Respond" (2023) 9

Figure 3: RaR dramatically improves performance across nine benchmark tasks, especially those requiring careful reasoning. Source: Deng et al., "Rephrase and Respond" (2023) 9

What makes this work is that the model is not just rephrasing for the user's benefit. It is rephrasing for its own. The act of restating a question in clearer terms is itself a form of reasoning. Socrates understood that forcing someone to define terms precisely often dissolved the original confusion entirely.

2. Elenchus: Cross-Examination for Consistency

Elenchus is "the central technique of the Socratic method" 12. It involves cross-examination: you take someone's stated belief, ask a series of probing questions, and test whether the belief holds up or collapses under its own contradictions.

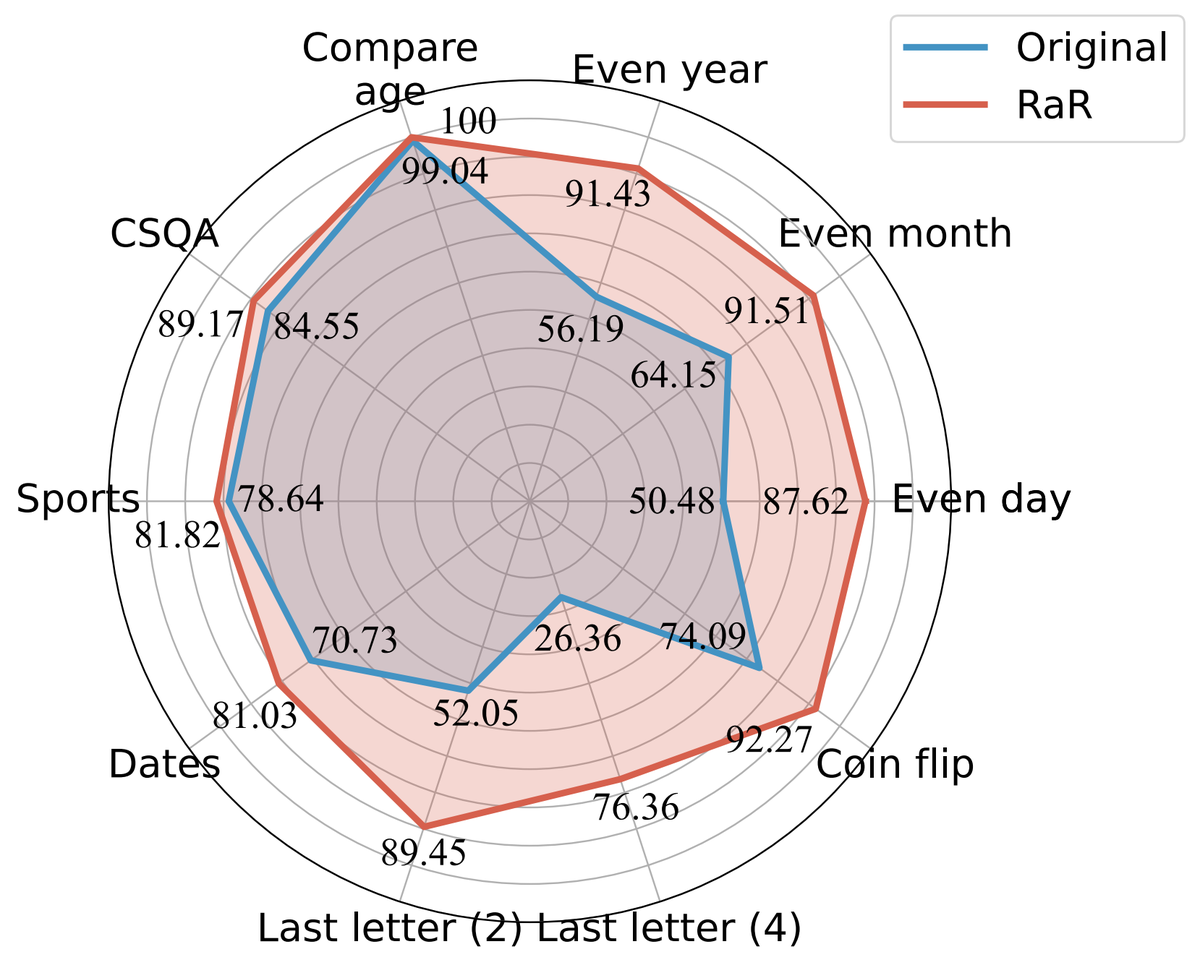

In LLM prompting, this maps directly onto self-consistency. Wang et al. introduced a method that "replaces the naive greedy decoding used in chain-of-thought prompting" by sampling "a diverse set of reasoning paths instead of only taking the greedy one, and then selects the most consistent answer by marginalizing out the sampled reasoning paths" 13. The improvements are substantial: GSM8K (+17.9%), SVAMP (+11.0%), AQuA (+12.2%), StrategyQA (+6.4%), and ARC-challenge (+3.9%) 14.

Figure 4: Self-consistency mirrors elenchus: testing multiple reasoning paths for internal coherence. Source: Wang et al., "Self-Consistency Improves Chain of Thought Reasoning in Language Models" (ICLR 2023) 13

Figure 4: Self-consistency mirrors elenchus: testing multiple reasoning paths for internal coherence. Source: Wang et al., "Self-Consistency Improves Chain of Thought Reasoning in Language Models" (ICLR 2023) 13

But here is where it gets interesting. When LLMs try to self-correct without external feedback, their performance actually degrades. On GSM8K, GPT-4 dropped from 95.5% accuracy to 89.0% after two rounds of self-correction 15. The fundamental issue is that "LLMs cannot properly judge the correctness of their reasoning" 16. Worse, on GSM8K, "74.7% of the time, GPT-3.5 retains its initial answer. Among the remaining instances, the model is more likely to modify a correct answer to an incorrect one than to revise an incorrect answer to a correct one" 17.

Socrates never questioned himself in a monologue. He needed Athens. The model needs external challenge too. Self-consistency works because it compares independent reasoning paths. Self-correction fails because a model reviewing its own single chain of thought lacks the adversarial tension that makes elenchus productive. An LLM talking to itself is not doing elenchus.

3. Dialectic: Truth Through Structured Debate

Socratic dialectic "involves exploring opposing viewpoints through dialogue or debate to arrive at a deeper understanding of a subject" 18. This is not polite discussion. It is structured confrontation.

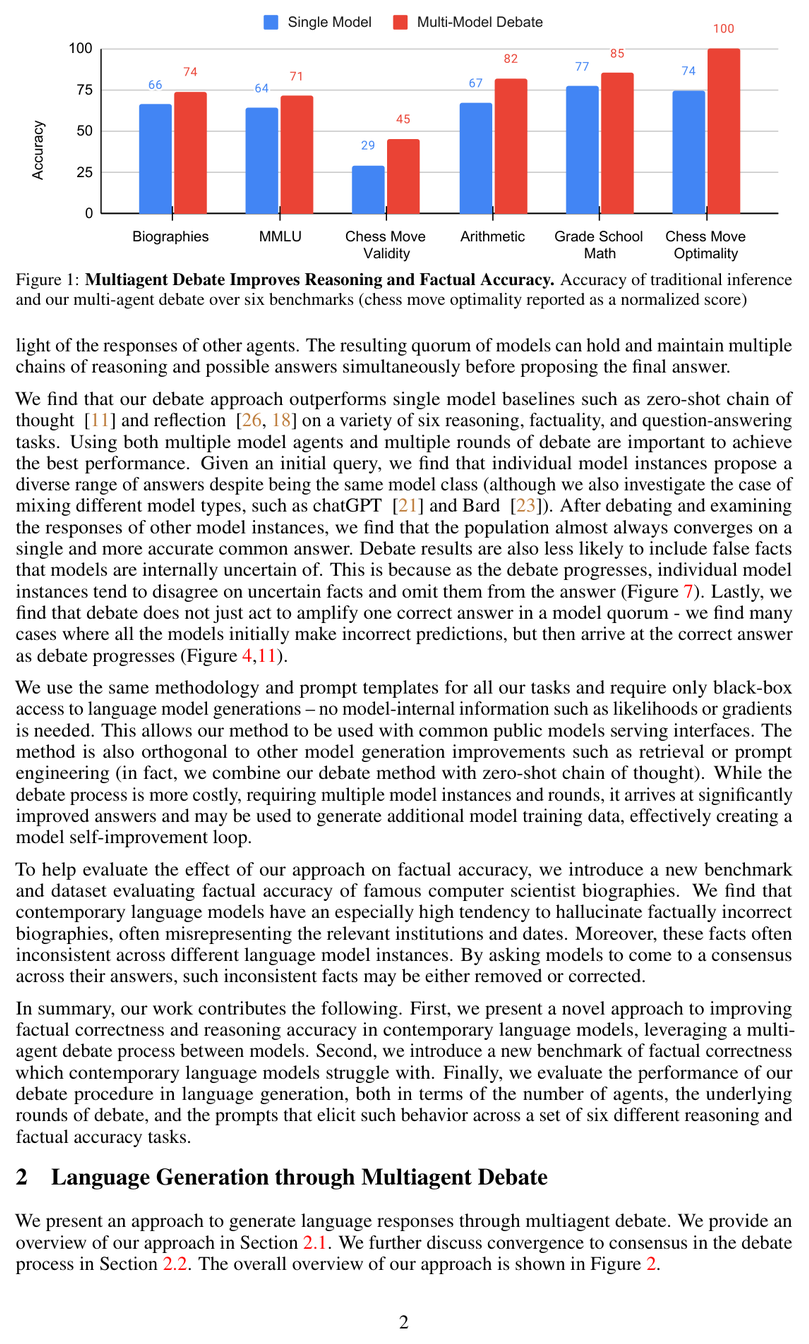

The modern implementation is multi-agent debate, and the results are striking. When three instances of ChatGPT debate an arithmetic problem (adding six random integers) over two rounds, accuracy jumps from 67.0% to 81.8% 19. More impressively, GPT-3.5-Turbo with Multi-Agent Debate "can even surpass the performance of GPT-4" on certain translation benchmarks 20.

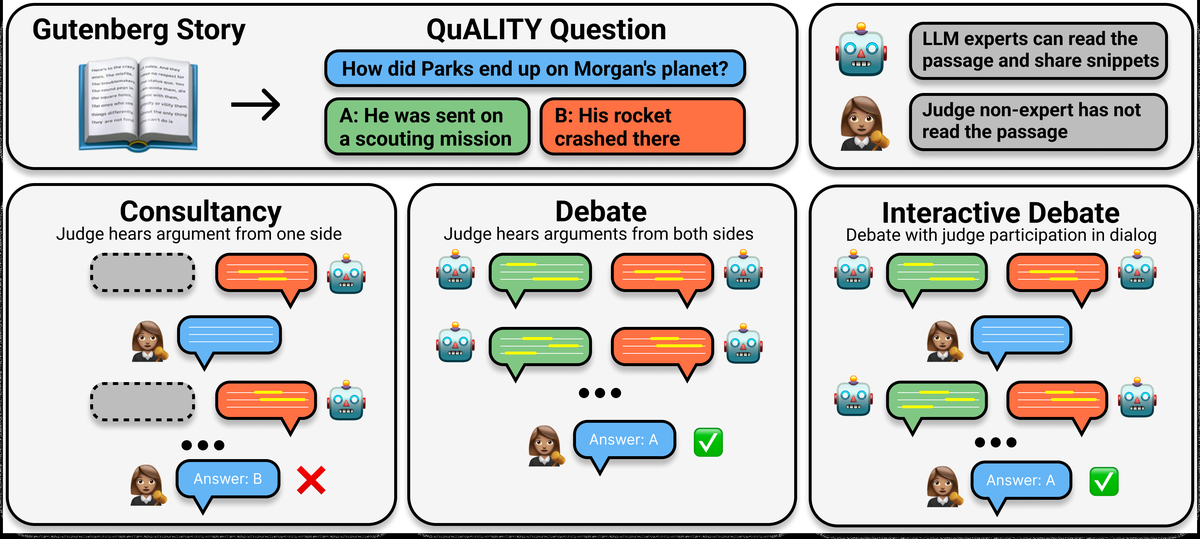

Figure 5: Three modes of AI debate mirror different aspects of Socratic dialectic. Source: Khan et al., "Debating with More Persuasive LLMs Leads to More Truthful Answers" (2024) 21

Figure 5: Three modes of AI debate mirror different aspects of Socratic dialectic. Source: Khan et al., "Debating with More Persuasive LLMs Leads to More Truthful Answers" (2024) 21

Anthropic's debate research adds another dimension. They found that "debate consistently helps both non-expert models and humans answer questions, achieving 76% and 88% accuracy respectively" where naive baselines only hit 48% and 60% 22. Critically, "optimising expert debaters for persuasiveness in an unsupervised manner improves non-expert ability to identify the truth in debates" 23. Stronger opponents produce truer outcomes.

But single-model reflection fails here too. Liang et al. identified a problem they call "Degeneration-of-Thought": "once the LLM has established confidence in its solutions, it is unable to generate novel thoughts later through reflection even if its initial stance is incorrect" 24. The three factors behind this collapse: bias and distorted perception, rigidity and resistance to change, and limited external feedback 25. Dialectic requires genuine opposition. Talking to yourself is not dialectic; it is rumination.

Figure 6: Multi-agent debate consistently outperforms single-model inference across reasoning and factuality benchmarks. Source: Du et al., "Improving Factuality and Reasoning through Multiagent Debate" (ICML 2024) 26

Figure 6: Multi-agent debate consistently outperforms single-model inference across reasoning and factuality benchmarks. Source: Du et al., "Improving Factuality and Reasoning through Multiagent Debate" (ICML 2024) 26

4. Maieutics: The Midwife Method

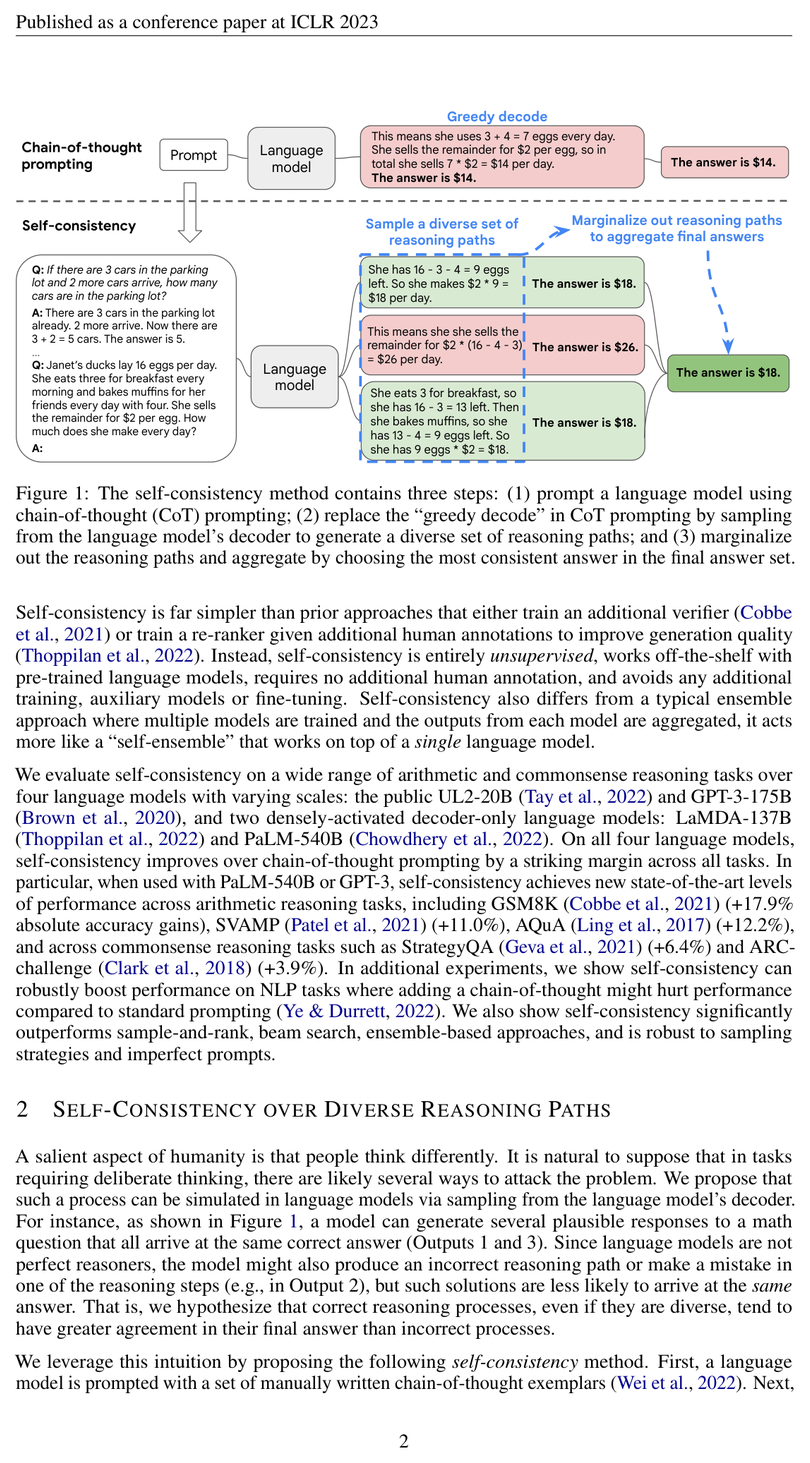

This is my favorite Socratic technique, and it produced what I consider the most elegant prompting method in the literature. Socrates described his practice as midwifery: "my concern is not with the body but with the soul that is experiencing birth pangs. And the highest achievement of my art is the power to try by every test to decide whether the offspring of a young person's thought is a false phantom or is something imbued with life and truth" 27.

The idea is that the learner already possesses the knowledge. The teacher's job is not to insert it but to draw it out. "Proponents of the Socratic method argue that, by coming to answers themselves, students better remember both the answer and the logical reasoning that led them there than they would if someone had simply announced a conclusion up front" 28.

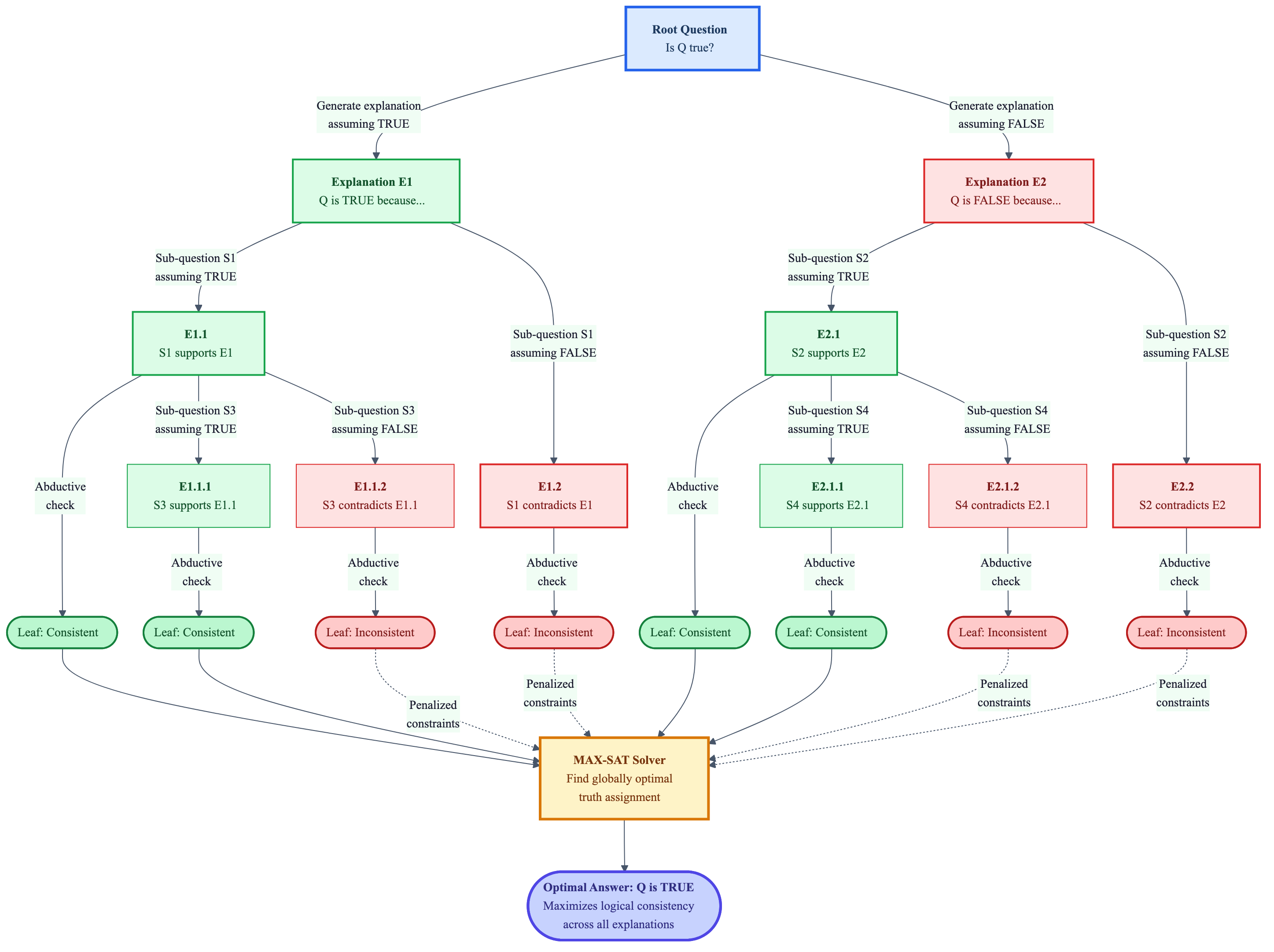

Jung et al. formalized this as Maieutic Prompting, which "infers a consistent set of answers to a question despite the unreliability of LLM generations, by defining a tree of abductively-verified and recursively-prompted explanations" 29. They then frame inference as a MAX-SAT satisfiability problem and solve it with an off-the-shelf solver 30. The result: "up to 20% better accuracy than state-of-the-art prompting methods on the GPT-3 (175B) language model, competitive even to a supervised model with orders of magnitude more labeled data" 31.

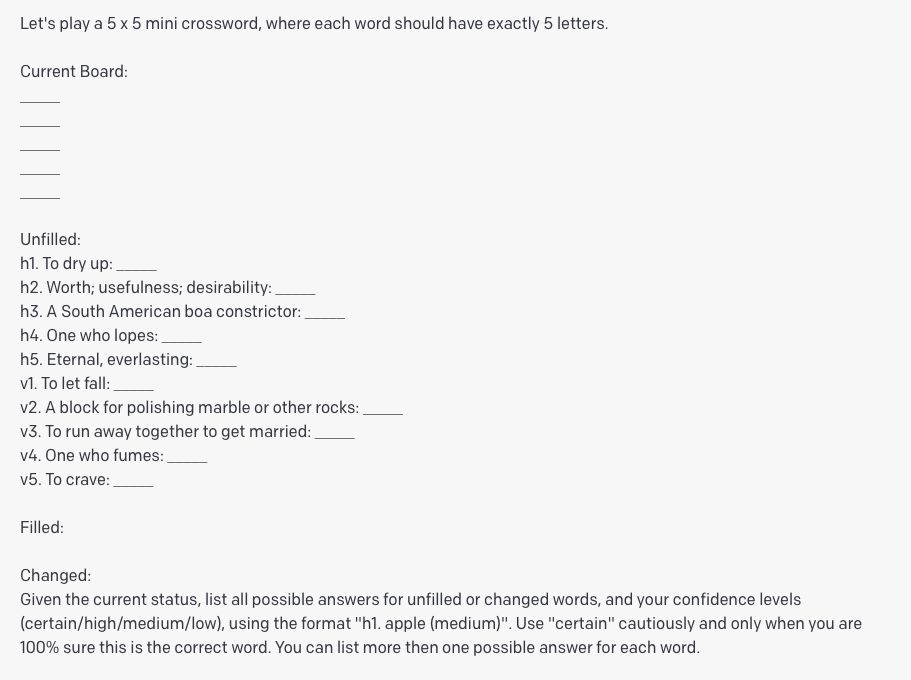

The insight that recursive exploration outperforms linear reasoning shows up independently in Tree of Thoughts. Yao et al. introduced a method that "generalizes over the popular Chain of Thought approach to prompting language models, and enables exploration over coherent units of text (thoughts) that serve as intermediate steps toward problem solving" 32. On the Game of 24 task, ToT achieved a 74% success rate while standard chain-of-thought prompting with GPT-4 solved only 4% 33. That is not an incremental improvement. That is the difference between a method that works and one that does not.

Figure 7: Tree of Thoughts applied to a crossword puzzle. The model explores multiple hypothesis branches, evaluates each, and backtracks from dead ends. Source: Yao et al., "Tree of Thoughts" (2023) 32

Figure 7: Tree of Thoughts applied to a crossword puzzle. The model explores multiple hypothesis branches, evaluates each, and backtracks from dead ends. Source: Yao et al., "Tree of Thoughts" (2023) 32

There is an elegant simplified version of this idea captured in Dave Hulbert's prompt: "Imagine three different experts are answering this question. All experts will write down 1 step of their thinking, then share it with the group. Then all experts will go on to the next step, etc. If any expert realises they're wrong at any point then they leave" 34. This prompt converts a monologue into a simulated maieutic dialogue, and it works surprisingly well in practice.

Figure 8: The maieutic prompting process visualized as a tree. Green paths support the TRUE hypothesis; red paths support FALSE. Leaf nodes are verified for logical consistency, and a MAX-SAT solver maximizes agreement across all explanations to select the optimal answer. Source: Generated based on Jung et al., "Maieutic Prompting" (2022) 29

Figure 8: The maieutic prompting process visualized as a tree. Green paths support the TRUE hypothesis; red paths support FALSE. Leaf nodes are verified for logical consistency, and a MAX-SAT solver maximizes agreement across all explanations to select the optimal answer. Source: Generated based on Jung et al., "Maieutic Prompting" (2022) 29

5. Generalization: From Specific to Universal

Socratic generalization means "drawing general principles from patterns that underlie observations and theories" 35. When Socrates asked about justice, he did not want one example. He wanted the principle that unified all examples.

This maps to chain-of-thought reasoning, where you show the model a few examples of step-by-step reasoning and ask it to generalize the pattern. Wei et al. demonstrated that "generating a chain of thought, a series of intermediate reasoning steps, significantly improves the ability of large language models to perform complex reasoning" 36. And it is an emergent ability: chain-of-thought "does not positively impact performance for small models, and only yields performance gains when used with models of approximately 100B parameters" 37.

I will be honest: this is the loosest of the six mappings. Chain-of-thought is a general reasoning scaffold, and calling it "Socratic generalization" stretches the metaphor more than the other five. But there is a genuine Socratic insight buried here: "prompts with higher reasoning complexity, e.g., with more reasoning steps, can achieve better performance on math problems" 38. More steps, more questions, better results. The zero-shot variant is telling too. Kojima et al. discovered that LLMs can generate reasoning steps without examples simply by appending "Let's think step by step" to a prompt 39. That is the LLM equivalent of Socrates saying "Well, let us reason it through together." No specific instruction on how to reason. Just an invitation to reason at all.

6. Counterfactual Reasoning: "What If Things Were Otherwise?"

Socrates often asked people to consider what would happen if their beliefs were wrong. "Counterfactual reasoning can be seen as a natural extension of the Socratic method, as both involve questioning assumptions and exploring alternative perspectives" 40.

This technique has creative applications. Chang demonstrated using counterfactual prompting to rewrite chapters in Chinese classical novels, asking the model to explore alternative histories and character decisions 41. But here too, I want to be direct about the limitations: "LLMs often struggle with counterfactual reasoning and frequently fail to maintain logical consistency or adjust to context shifts" 42. This is the frontier where the Socratic-LLM mapping is least mature, and that is itself interesting.

Socrates never claimed his method produced certainty. As Bertrand Russell put it, the result of such questioning is to "substitute articulate hesitation for inarticulate certainty" 43. Counterfactual prompting does exactly that: it trades confident wrong answers for uncertain right questions.

The Bigger Pattern: Questions Over Answers

Looking across all six techniques, a pattern emerges that I think is underappreciated. The most effective prompting strategies share a single structural property: they convert answer-generation tasks into question-generation tasks.

The Self-Ask method makes this explicit. Press et al. introduced a technique "in which the model explicitly asks itself (and then answers) follow-up questions before answering the initial question" 44. They measured a "consistent compositionality gap of approximately 40% across model sizes" 45, meaning models could answer sub-questions correctly but failed when those questions needed to be composed. Self-Ask narrows this gap by making the decomposition explicit. The model becomes its own Socratic questioner, breaking problems into parts it can handle.

Figure 9: Self-Ask in action. The model generates and answers its own sub-questions before tackling the main query. Source: Press et al., "Measuring and Narrowing the Compositionality Gap in Language Models" (2023) 44

Figure 9: Self-Ask in action. The model generates and answers its own sub-questions before tackling the main query. Source: Press et al., "Measuring and Narrowing the Compositionality Gap in Language Models" (2023) 44

Self-consistency generates multiple reasoning paths (implicitly asking "but what if I reasoned differently?"). Multi-agent debate forces models to question each other's positions. Tree of Thoughts asks "is this thought promising?" at each branch point. Even something as simple as "think step by step" works because it converts a direct question into a sequence of smaller, more manageable questions. The comprehensive survey by Schulhoff et al. cataloged 58 distinct prompting techniques 46, and a remarkable number of them are variations on this single theme: get the model to question before it answers.

The Framework That Ties It Together

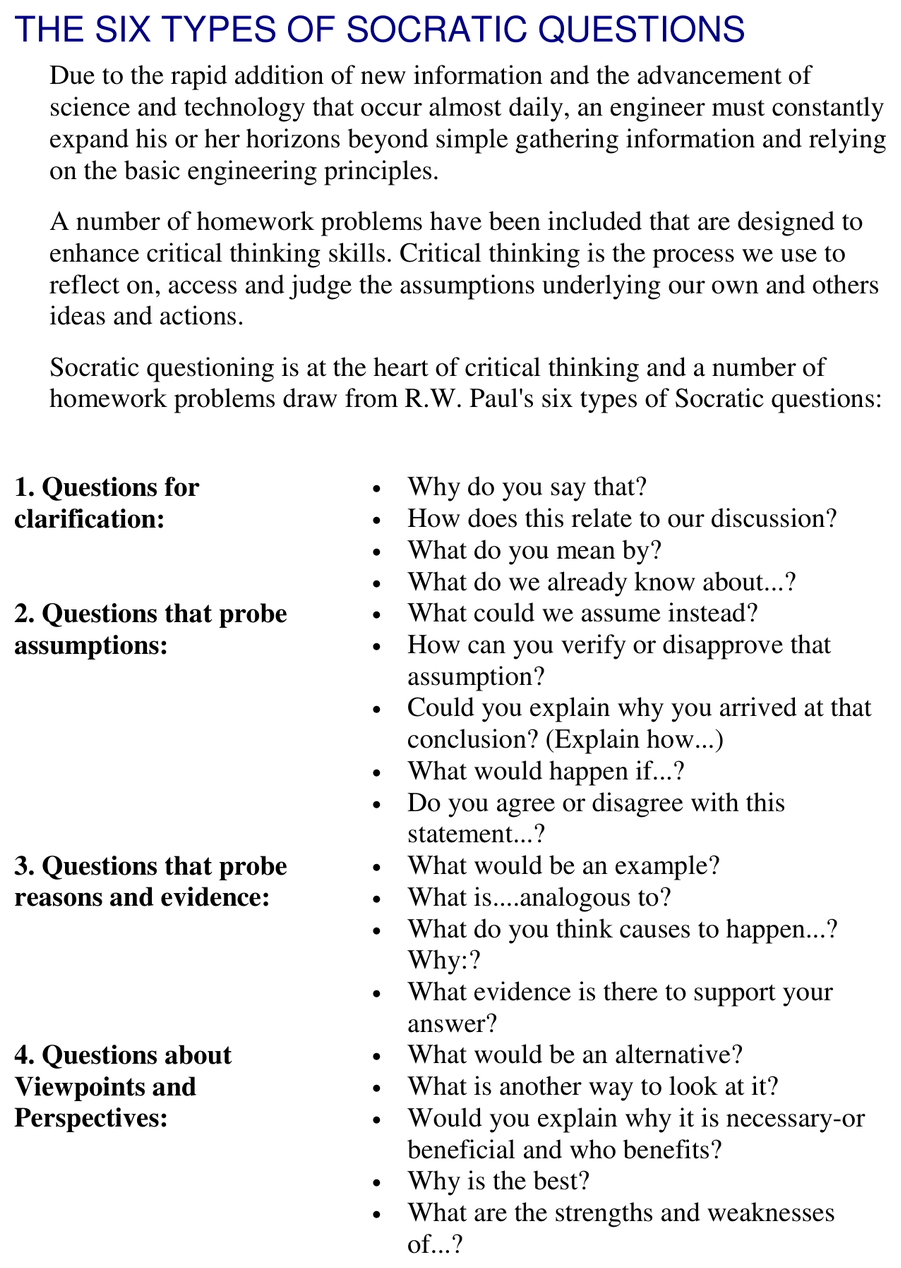

R.W. Paul's taxonomy of Socratic questions provides the connective tissue 47. His six types map cleanly onto prompt engineering patterns:

Figure 10: R.W. Paul's six types of Socratic questions, the classical framework underlying modern prompting strategies. Source: Paul's Six Types of Socratic Questions, University of Michigan 47

Figure 10: R.W. Paul's six types of Socratic questions, the classical framework underlying modern prompting strategies. Source: Paul's Six Types of Socratic Questions, University of Michigan 47

| Socratic Question Type | Prompting Technique | What It Does |

|---|---|---|

| Questions for clarification | Rephrase and Respond | Forces the model to restate the problem precisely |

| Questions probing assumptions | Self-consistency | Tests whether the model's reasoning holds from multiple angles |

| Questions probing evidence | Chain-of-thought | Requires step-by-step justification |

| Questions about viewpoints | Multi-agent debate | Introduces adversarial perspectives |

| Questions about implications | Tree of Thoughts | Explores consequences of different reasoning paths |

| Questions about the question | Self-Ask / Maieutic prompting | Recursively examines why each answer might be right or wrong |

This is not just a mapping exercise. It reveals something about why these techniques work. They work because they force the model out of pattern completion and into something that resembles reasoning. The structure matters more than the content: chain-of-thought works not because of the specific examples you provide but because it imposes a reasoning structure. Self-consistency works because it imposes consistency checking. Tree of Thoughts works because it imposes search and backtracking.

Here is a minimal implementation combining both techniques.

from collections import Counter

from openai import OpenAI

client = OpenAI() # uses OPENAI_API_KEY env var

def socratic_prompt(question: str) -> dict:

"""Combine Socratic Definition (RaR) + Elenchus (Self-Consistency)."""

# Step 1: DEFINITION -- Rephrase and Respond (RaR)

# Socrates asked "What do you mean by that?" before engaging.

# RaR does the same: clarify the question before answering.

rephrase = client.chat.completions.create(

model="gpt-4",

messages=[{"role": "user", "content": (

"Before answering the following question, first rephrase "

"it to be more precise and unambiguous. Restate any "

"implicit assumptions explicitly. Return only the "

"rephrased question.\n\n"

f"Original question: {question}"

)}],

temperature=0.3,

)

clarified = rephrase.choices[0].message.content

# Step 2: ELENCHUS -- Self-Consistency via diverse reasoning

# Socrates probed beliefs from multiple angles. We sample 3

# reasoning paths at different temperatures, then vote.

answers = []

for temp in [0.2, 0.7, 1.0]:

response = client.chat.completions.create(

model="gpt-4",

messages=[{"role": "user", "content": (

"Answer step by step, then state your final answer "

f"after 'ANSWER:'.\n\nQuestion: {clarified}"

)}],

temperature=temp,

)

raw = response.choices[0].message.content

answer = raw.split("ANSWER:")[-1].strip() if "ANSWER:" in raw else raw

answers.append(answer)

# Step 3: Majority vote -- the answer that survives cross-examination

winner = Counter(answers).most_common(1)[0][0]

return {"clarified_question": clarified, "answer": winner, "paths": answers}

The pattern is simple: ask the question better (Definition), probe it from multiple angles (Elenchus), keep the answer that survives (Self-Consistency). Three Socratic principles in forty lines of Python.

What Socrates Reveals About LLMs

I want to end where Socrates would have ended: with the questions still unresolved.

Does the model understand, or does it merely perform understanding? The Degeneration-of-Thought problem, where models cannot escape their initial confident position, suggests that whatever LLMs do when they "reason," it is not the same thing humans do. Socratic inquiry requires the capacity to be genuinely surprised by where the questioning leads. Whether LLMs have that capacity is an open question.

Why does dialogue work better than monologue? The multi-agent debate results are clear, and so is the self-correction failure data. But we do not have a satisfying mechanistic explanation. When GPT-3.5 with multi-agent debate surpasses GPT-4 on certain tasks 20, something interesting is happening at the computational level. What is it?

What would Socrates make of a partner that cannot say "I don't know"? Socrates' greatest virtue was his awareness of his own ignorance. "While the Sophists tried to demonstrate their knowledge, Socrates did his best to demonstrate his (and everybody else's) ignorance" 48. LLMs are, in some fundamental sense, Sophists. They generate confident-sounding text regardless of whether they actually know what they are talking about. "One challenge with LLMs is that they can deliver both correct and incorrect answers with the same level of confidence, making it hard to know which ones to trust" 49. The Socratic method was designed to combat exactly this problem.

Maybe that is the deepest lesson here. The prompt engineering techniques that work best are the ones that force models out of confident monologue and into the productive uncertainty of genuine inquiry. Socrates knew that the beginning of wisdom is admitting you do not know. The best prompting strategies make LLMs do something similar: generate multiple hypotheses, test them against each other, backtrack when they fail, and converge on answers that survive cross-examination rather than answers that merely sound right.

Socrates was executed for asking too many questions. Your GPU bill will go up. But the answers will be better.

References

Footnotes

-

Chang, E.Y. (2023). Prompting Large Language Models With the Socratic Method. IEEE CCWC 2023. arXiv:2303.08769. ↩ ↩2

-

Jung, J., Qin, L., Welleck, S., Brahman, F., Bhagavatula, C., Le Bras, R., & Choi, Y. (2022). Maieutic Prompting: Logically Consistent Reasoning with Recursive Explanations. EMNLP 2022. ↩

-

Chang (2023). Six techniques connected to inductive, deductive, and abductive reasoning. arXiv:2303.08769. ↩

-

Chang (2023). On LLMs as Socratic partners. arXiv:2303.08769. ↩

-

Chang (2023). Error rate of explanation-based prompting on simple math. arXiv:2303.08769. ↩

-

Plato, Apology. The Oracle at Delphi account. Cited via Wikipedia, "Socratic Method." ↩

-

Philosophy Break. Maden, J. (2021). "The Socratic Method: What Is It and How Can You Use It?" ↩

-

Chang (2023). Definition method. arXiv:2303.08769. ↩

-

Deng, Y., Zhang, W., Chen, Z., & Gu, Q. (2023). Rephrase and Respond: Let Large Language Models Ask Better Questions for Themselves. arXiv:2311.04205. ↩ ↩2

-

Deng et al. (2023). arXiv:2311.04205. ↩

-

Deng et al. (2023). RaR complementary to CoT. arXiv:2311.04205. ↩

-

Wikipedia, "Socratic Method." Definition of elenchus from Ancient Greek. ↩

-

Wang, X., Wei, J., Schuurmans, D., Le, Q., Chi, E., Narang, S., Chowdhery, A., & Zhou, D. (2023). Self-Consistency Improves Chain of Thought Reasoning in Language Models. ICLR 2023. ↩ ↩2

-

Wang et al. (2023). Self-consistency benchmark improvements. ICLR 2023. ↩

-

Huang, J., Chen, X., Mishra, S., Zheng, H.S., Yu, A.W., Song, X., & Zhou, D. (2024). Large Language Models Cannot Self-Correct Reasoning Yet. ICLR 2024. ↩

-

Huang et al. (2024). ICLR 2024. ↩

-

Huang et al. (2024). Self-correction direction bias on GSM8K. ICLR 2024. ↩

-

Chang (2023). Dialectic definition. arXiv:2303.08769. ↩

-

Du, Y., Li, S., Torralba, A., Tenenbaum, J.B., & Mordatch, I. (2024). Improving Factuality and Reasoning in Language Models through Multiagent Debate. ICML 2024. ↩

-

Liang, T., He, Z., Jiao, W., Wang, X., Wang, Y., Wang, R., Yang, Y., Tu, Z., & Shi, S. (2023). Encouraging Divergent Thinking in Large Language Models through Multi-Agent Debate. arXiv:2305.19118. ↩ ↩2

-

Khan, A., Hughes, J., Valentine, D., Ruis, L., Sachan, K., Raber, A., Gretton, A., & Perez, E. (2024). Debating with More Persuasive LLMs Leads to More Truthful Answers. arXiv:2402.06782. ↩

-

Khan et al. (2024). Debate accuracy vs. naive baselines. arXiv:2402.06782. ↩

-

Khan et al. (2024). Persuasiveness optimization. arXiv:2402.06782. ↩

-

Liang et al. (2023). Degeneration-of-Thought problem. arXiv:2305.19118. ↩

-

Liang et al. (2023). Three factors behind Degeneration-of-Thought. arXiv:2305.19118. ↩

-

Du et al. (2024). Multi-agent debate results. ICML 2024. ↩

-

Plato, Theaetetus. Socrates' midwifery metaphor. Cited via Philosophy Break (2021). ↩

-

Philosophy Break. Maden, J. (2021). Learning retention argument. ↩

-

Jung et al. (2022). Maieutic Prompting method. EMNLP 2022. ↩ ↩2

-

Jung et al. (2022). MAX-SAT formulation. EMNLP 2022. ↩

-

Jung et al. (2022). Performance vs. state-of-the-art. EMNLP 2022. ↩

-

Yao, S., Yu, D., Zhao, J., Shafran, I., Griffiths, T.L., Cao, Y., & Narasimhan, K. (2023). Tree of Thoughts: Deliberate Problem Solving with Large Language Models. NeurIPS 2023. ↩ ↩2

-

Yao et al. (2023). ToT vs. CoT on Game of 24. NeurIPS 2023. ↩

-

Hulbert, D. Tree-of-Thought Prompting. As cited in Prompting Guide, promptingguide.ai. ↩

-

Chang (2023). Generalization method definition. arXiv:2303.08769. ↩

-

Wei, J., Wang, X., Schuurmans, D., Bosma, M., Chi, E., Le, Q., & Zhou, D. (2022). Chain-of-Thought Prompting Elicits Reasoning in Large Language Models. NeurIPS 2022. ↩

-

Wei et al. (2022). Emergent ability of model scale. NeurIPS 2022. ↩

-

Qiao, S., Ou, Y., Zhang, N., et al. (2023). Reasoning with Language Model Prompting: A Survey. ACL 2023. ↩

-

Kojima et al. (2022), as discussed in Qiao et al. (2023). Zero-shot CoT discovery. ↩

-

Chang (2023). Connection between counterfactual reasoning and Socratic method. arXiv:2303.08769. ↩

-

Chang (2023). Counterfactual creative writing experiments. arXiv:2303.08769. ↩

-

On the Eligibility of LLMs for Counterfactual Reasoning: A Decompositional Study. (2025). arXiv:2505.11839. ↩

-

Russell, B. As cited in Philosophy Break (2021). On Socratic questioning. ↩

-

Press, O., Zhang, M., Min, S., Schmidt, L., Smith, N.A., & Lewis, M. (2023). Measuring and Narrowing the Compositionality Gap in Language Models. Findings of ACL 2023. ↩ ↩2

-

Press et al. (2023). 40% compositionality gap. Findings of ACL 2023. ↩

-

Schulhoff, S., Ilie, M., Balepur, N., et al. (2024). The Prompt Report: A Systematic Survey of Prompting Techniques. arXiv:2406.06608. ↩

-

Paul, R.W. & Elder, L. (2006). The Thinker's Guide to the Art of Socratic Questioning. Foundation for Critical Thinking. See also: Six Types of Socratic Questions, University of Michigan. ↩ ↩2

-

Philosophy Break (2021). Socrates vs. Sophists distinction. ↩

-

Learn Prompting. "Introduction to Self-Criticism Prompting Techniques." ↩