MolBERT: Teaching Transformers to Read the Language of Chemistry

Every drug that reaches your medicine cabinet survived a brutal gauntlet. "The average cost of developing a new drug was ~1 billion dollars and has been ever increasing."1 Most candidates fail not because they don't work, but because they can't get where they need to go, or they damage tissues they shouldn't touch. What if we could predict these failures computationally, before synthesizing a single molecule?

This is the promise of molecular representation learning. And the approach that has captured the most attention? Taking BERT (the transformer architecture that transformed how machines understand language) and teaching it to read chemical structures instead.

The insight behind MolBERT is deceptively simple. Molecules have their own written language called SMILES. Just as BERT learned to understand English by predicting masked words, MolBERT learns to understand chemistry by predicting masked atoms. But here's what makes this genuinely interesting: "the drug-like chemical space is enormous (the lower estimation is 10^23 molecules)."2 That's more than all the grains of sand on Earth. No database could ever enumerate them all. "Currently there are databases that enumerate most fragment-like molecules with up to 13 (975 million molecules)" and "17 (166 billion molecules) heavy atoms."34 Even these massive collections barely scratch the surface.

So how do we build models that can generalize across this incomprehensibly vast space? Let's start with the language molecules speak.

SMILES: The Chemistry World's Compression Algorithm

When chemists need to communicate molecular structures through text, they use SMILES: Simplified Molecular Input Line Entry System. "A SMILES sequence comprises symbols representing molecular structures."5

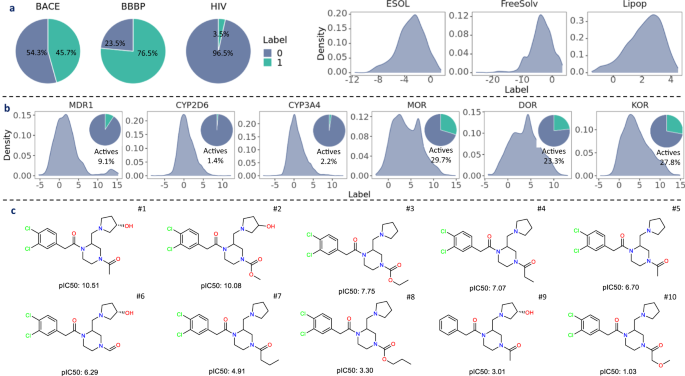

Consider aspirin. In 2D, it's a benzene ring with some functional groups attached. As a SMILES string: CC(=O)OC1=CC=CC=C1C(=O)O. Each character means something specific. C is carbon. =O is a double-bonded oxygen. "The ring structure is represented by adding the same number after the start atom and end atom of the ring,"6 which is why you see C1 at the start and C1 later to mark where the benzene ring closes.

Here is something crucial about SMILES that makes it both powerful and tricky: "A molecule can be represented by different SMILES sequences; e.g., CC(=O)C and C(=O)CC represent the same molecular structure."7 At first glance, this non-uniqueness seems like a bug. But researchers turned it into a feature.

Figure 1: Different SMILES representations of the same molecular structure. Each string encodes identical chemistry, enabling powerful data augmentation. Source: SMILES Enumeration as Data Augmentation

Figure 1: Different SMILES representations of the same molecular structure. Each string encodes identical chemistry, enabling powerful data augmentation. Source: SMILES Enumeration as Data Augmentation

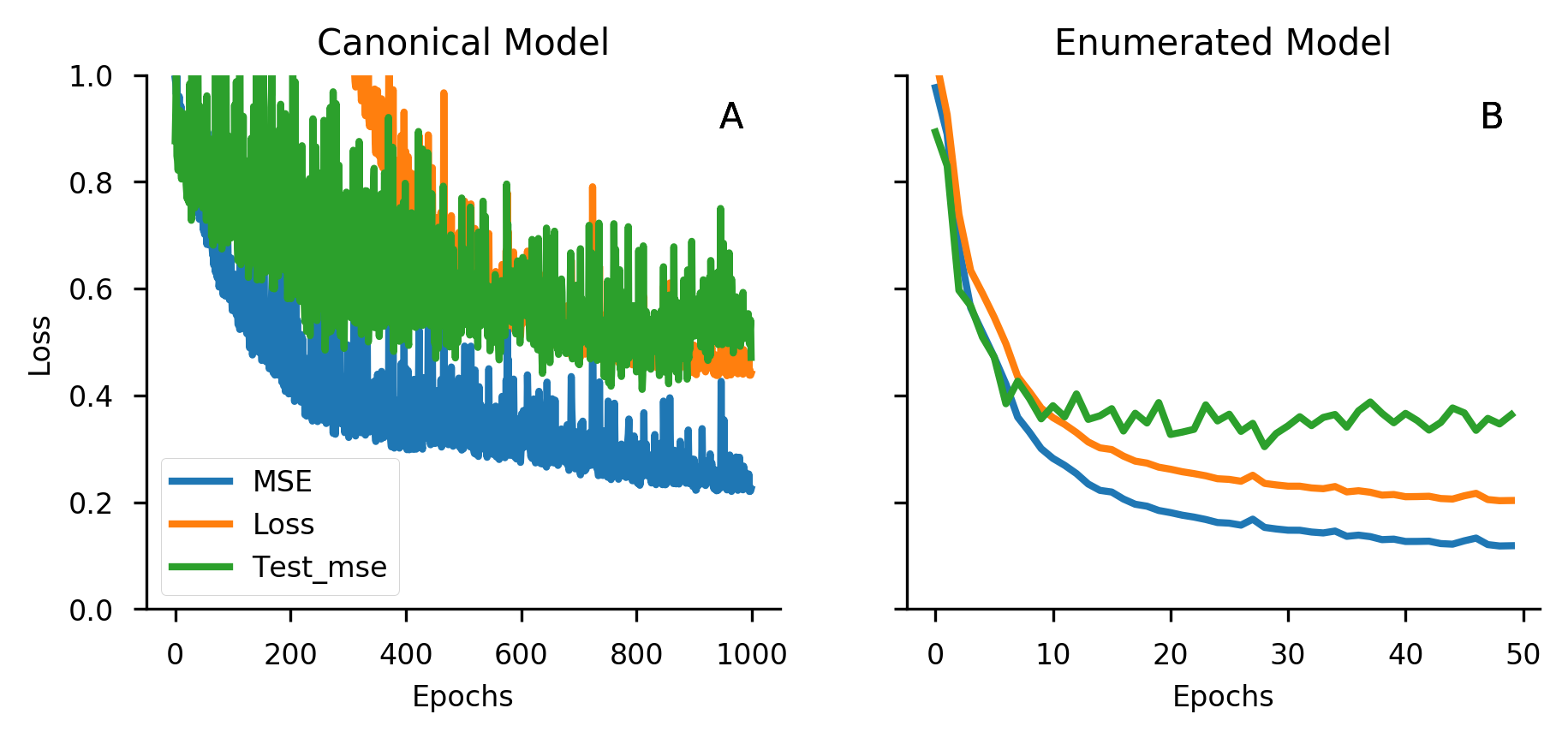

"Models that use LSTM cells trained with 1 million randomized SMILES, a non-unique molecular string representation, are able to generalize to larger chemical spaces than the other approaches."8 This is data augmentation for free. The same molecule can appear as 10, 100, or even 1000 different valid SMILES strings, effectively multiplying your training data without requiring new chemistry.

The results speak for themselves: "The best canonical SMILES model was only able to enumerate 72.8% of GDB-13 compared to the 83.0% of the restricted randomized SMILES."9 That 10% gap represents millions of molecules. Even more striking: "the model trained with randomized SMILES was able to generate at least double the amount of unique molecules with the same distribution of properties comparing to one trained with canonical SMILES."10

Figure 2: Randomized SMILES augmentation significantly improves molecular generative model capabilities compared to using only canonical SMILES. Source: Randomized SMILES Improve Molecular Generative Models, Journal of Cheminformatics

Figure 2: Randomized SMILES augmentation significantly improves molecular generative model capabilities compared to using only canonical SMILES. Source: Randomized SMILES Improve Molecular Generative Models, Journal of Cheminformatics

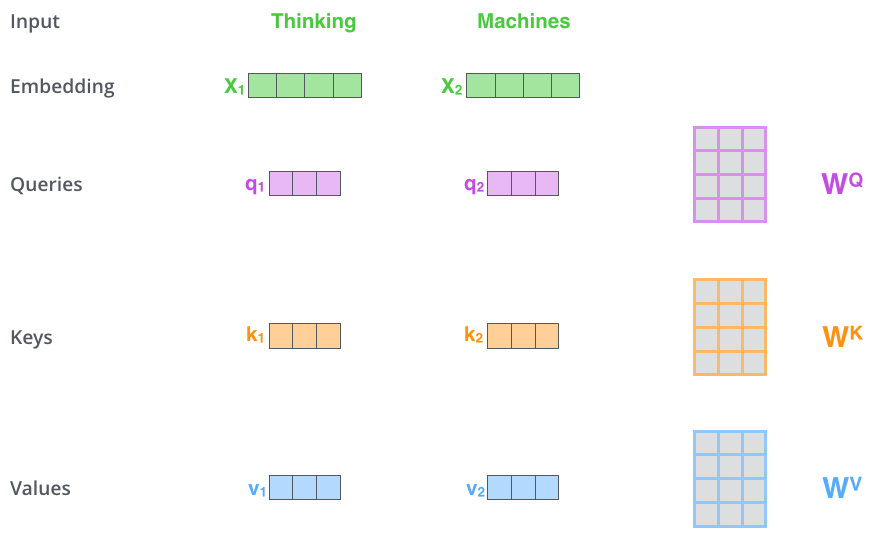

From Text to Chemistry: The Transformer Architecture

To understand MolBERT, we need to understand the transformer architecture it builds upon. "The Transformer was proposed in the paper Attention is All You Need."11 Its biggest benefit comes from "how The Transformer lends itself to parallelization,"12 allowing training on massive datasets that would be impractical with sequential models like RNNs.

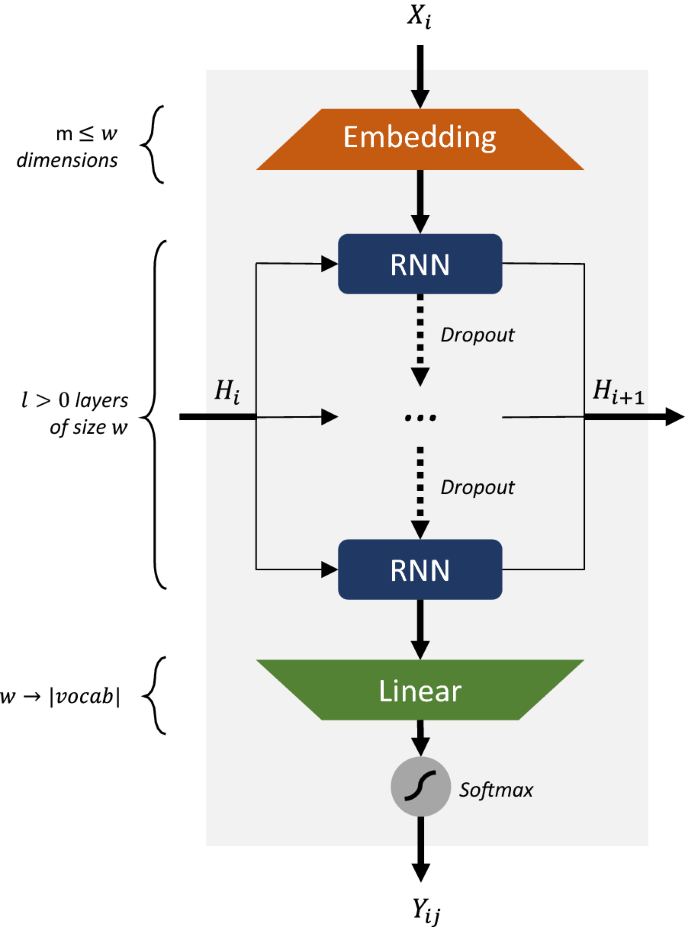

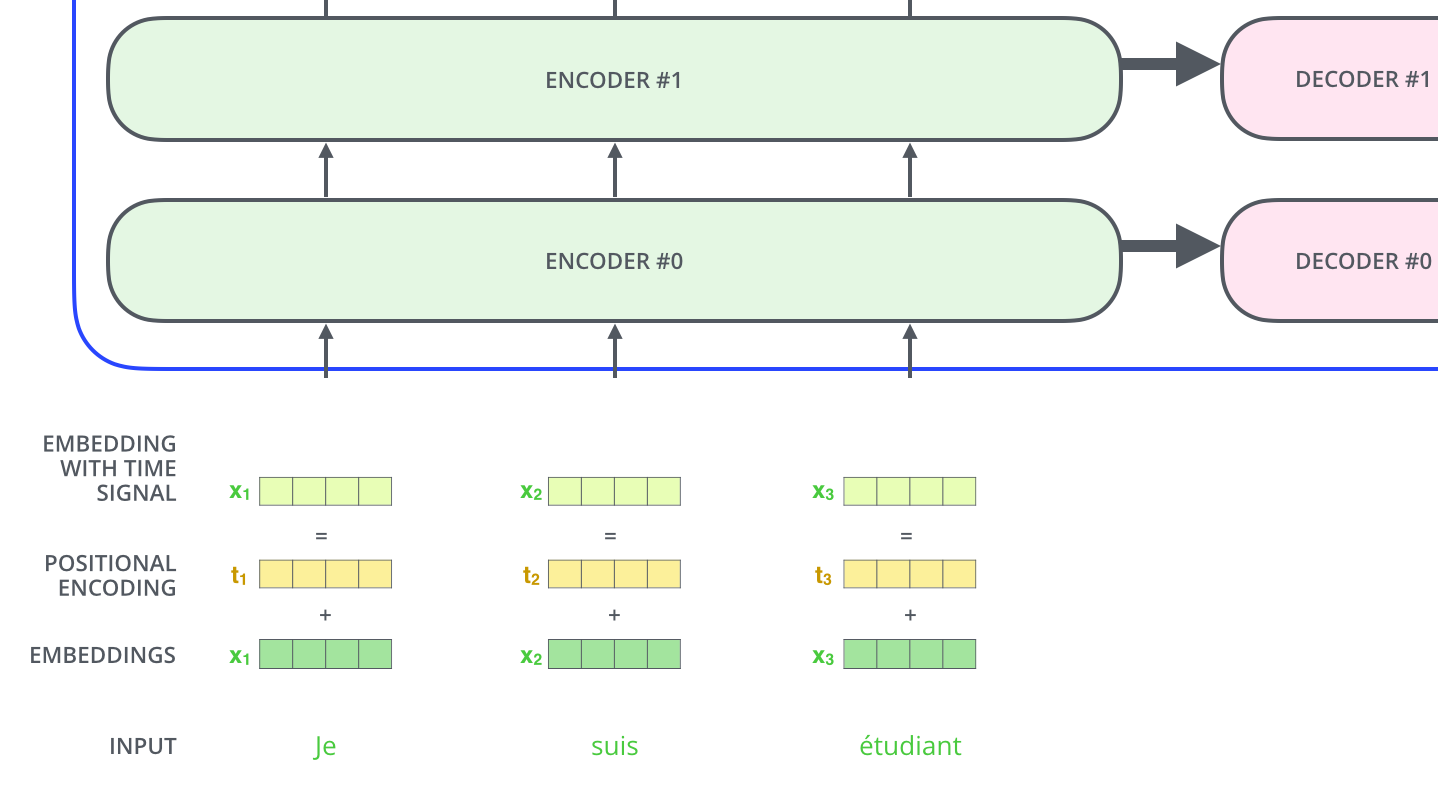

The architecture has two main components: encoders and decoders. MolBERT (like BERT) uses only the encoder stack. "The encoding component is a stack of encoders (the paper stacks six of them on top of each other)."13

Figure 3: The Transformer architecture stacks multiple encoder blocks. MolBERT uses the encoder portion (left side) to process SMILES sequences. Source: The Illustrated Transformer by Jay Alammar (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

Figure 3: The Transformer architecture stacks multiple encoder blocks. MolBERT uses the encoder portion (left side) to process SMILES sequences. Source: The Illustrated Transformer by Jay Alammar (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

"Each word is embedded into a vector of size 512."14 In MolBERT's case, each SMILES token gets embedded into a similar high-dimensional space. These vectors flow through the encoder stack, getting progressively enriched with contextual information. But how does context actually flow between positions?

Self-Attention: How Transformers Read Context

This is where transformers become powerful. "Self attention allows it to look at other positions in the input sequence for clues that can help lead to a better encoding for this word."15

Consider the sentence "The animal didn't cross the street because it was too tired." What does "it" refer to? For humans, it's obvious: the animal. For a machine processing words sequentially, this reference is challenging. "Self-attention allows it to associate 'it' with 'animal'."16

In molecular contexts, this matters enormously. A carbonyl group behaves differently depending on its neighbors. Is it part of an ester, an amide, or an aldehyde? Self-attention lets the model consider the entire molecular context when encoding each atom.

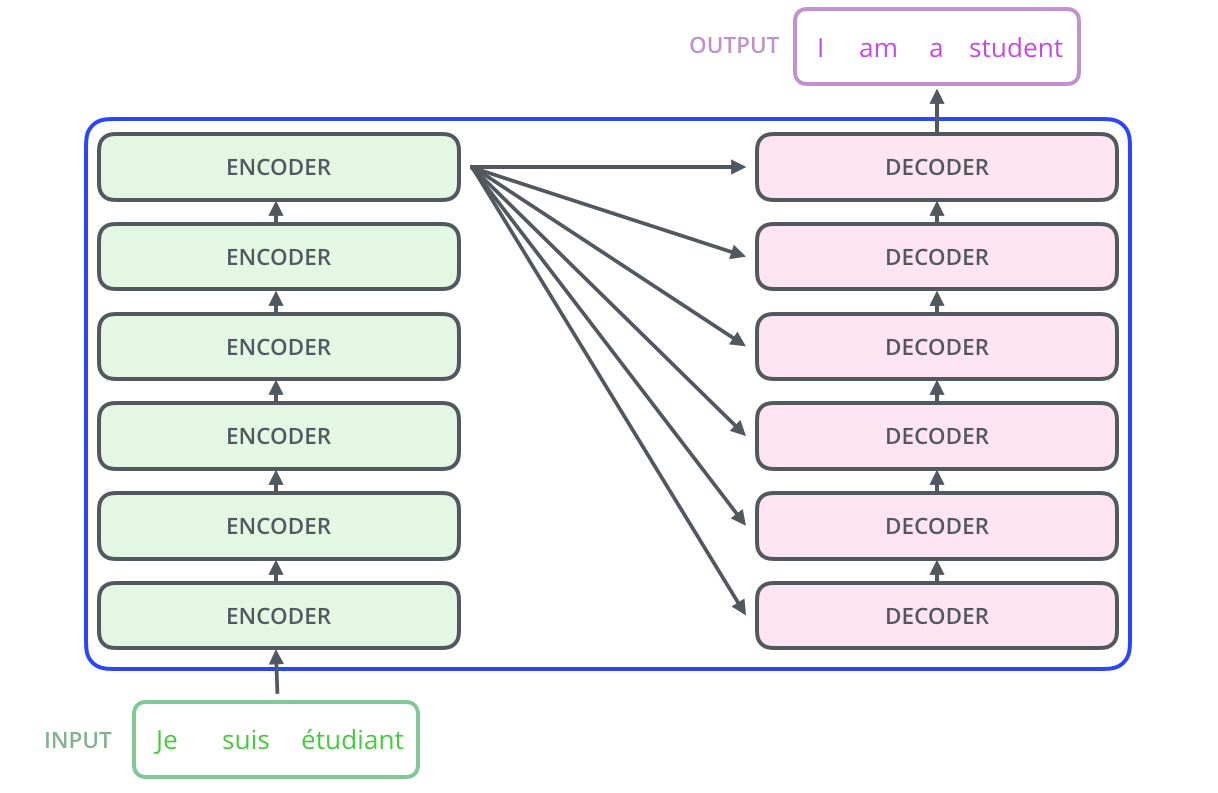

Figure 4: Self-attention computes relationships between all positions using Query, Key, and Value vectors. Source: The Illustrated Transformer by Jay Alammar (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

Figure 4: Self-attention computes relationships between all positions using Query, Key, and Value vectors. Source: The Illustrated Transformer by Jay Alammar (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

"The first step in calculating self-attention is to create three vectors from each of the encoder's input vectors... a Query vector, a Key vector, and a Value vector."17 "Their dimensionality is 64, while the embedding and encoder input/output vectors have dimensionality of 512."18

Think of it as a lookup system. The Query asks "what am I looking for?" The Key answers "what do I contain?" The Value says "here's what to retrieve if matched." When a Query matches strongly with certain Keys, the corresponding Values contribute more to the output. This computation happens in parallel across all positions.

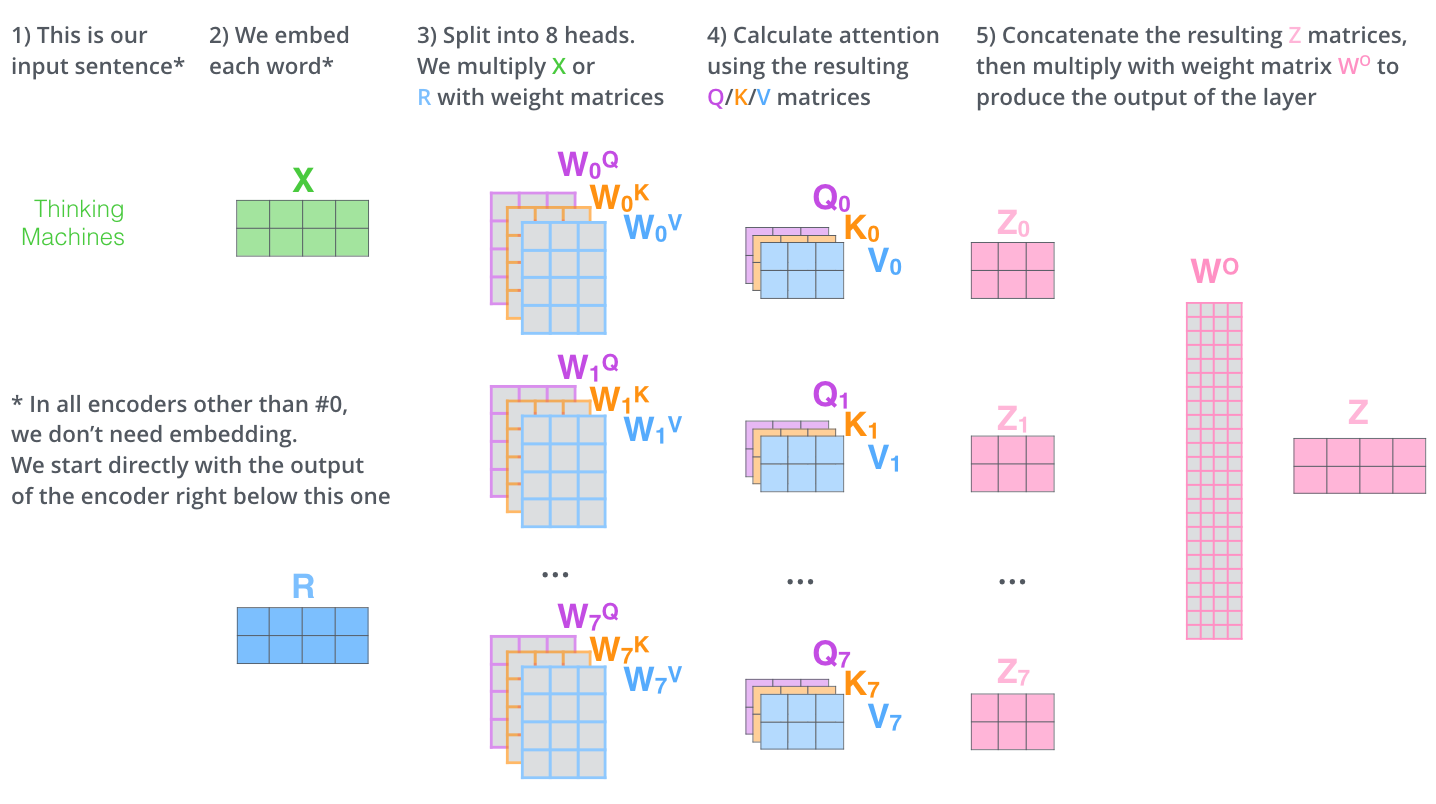

Multi-Head Attention: Learning Multiple Relationship Types

"The paper further refined the self-attention layer by adding a mechanism called 'multi-headed' attention."19 Instead of computing attention once, "the Transformer uses eight attention heads, so we end up with eight sets for each encoder/decoder."20 Each head can learn to focus on different types of relationships: one head might track ring closures, another might focus on electronegative atoms, and yet another on chain lengths.

Figure 5: Multi-head attention allows the model to jointly attend to information from different representation subspaces. Eight parallel attention heads learn complementary patterns. Source: The Illustrated Transformer by Jay Alammar (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

Figure 5: Multi-head attention allows the model to jointly attend to information from different representation subspaces. Eight parallel attention heads learn complementary patterns. Source: The Illustrated Transformer by Jay Alammar (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

There's one more crucial component. SMILES strings are sequences where order matters. C(=O)O is different from O(=C)O. "To give the model a sense of the order of the words, we add positional encoding vectors."21 These sinusoidal functions let the model know where each token appears in the sequence.

Figure 6: Positional encodings are added to token embeddings so the model can distinguish different positions in the SMILES sequence. Source: The Illustrated Transformer by Jay Alammar (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

Figure 6: Positional encodings are added to token embeddings so the model can distinguish different positions in the SMILES sequence. Source: The Illustrated Transformer by Jay Alammar (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

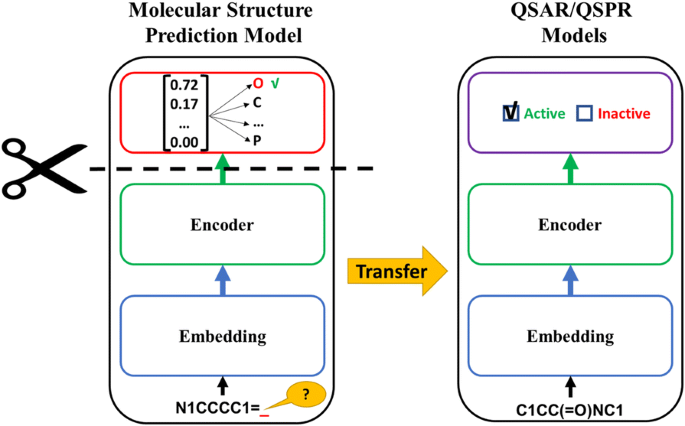

MolBERT Architecture: BERT Meets Chemistry

MolBERT adapts this architecture specifically for molecular sequences. "MolBERT is pretrained on a corpus of about 1.6M SMILES strings, which improves prediction performance on six benchmark datasets."22

The architecture details reveal a model designed for molecular complexity: "MolBERT is pretrained on a vocabulary of 42 tokens and a maximum sequence length of 128 characters."23 That vocabulary includes atoms (C, N, O, S, etc.), bond types (=, #, :), ring indicators (1-9), and structural markers (parentheses, brackets). Compare this to BERT's vocabulary of 30,000+ WordPiece tokens; the molecular alphabet is small, but the grammar is strict.

"MolBERT uses the BERTBase architecture with an output embedding size of 768, 12 BERT encoder layers, 12 attention heads, and a hidden size of 3072, resulting in about 85M parameters."24

Figure 7: Transfer learning approach for molecular property prediction, showing how pre-trained representations are fine-tuned for downstream tasks. Source: Inductive Transfer Learning for Molecular Activity Prediction, Journal of Cheminformatics

Figure 7: Transfer learning approach for molecular property prediction, showing how pre-trained representations are fine-tuned for downstream tasks. Source: Inductive Transfer Learning for Molecular Activity Prediction, Journal of Cheminformatics

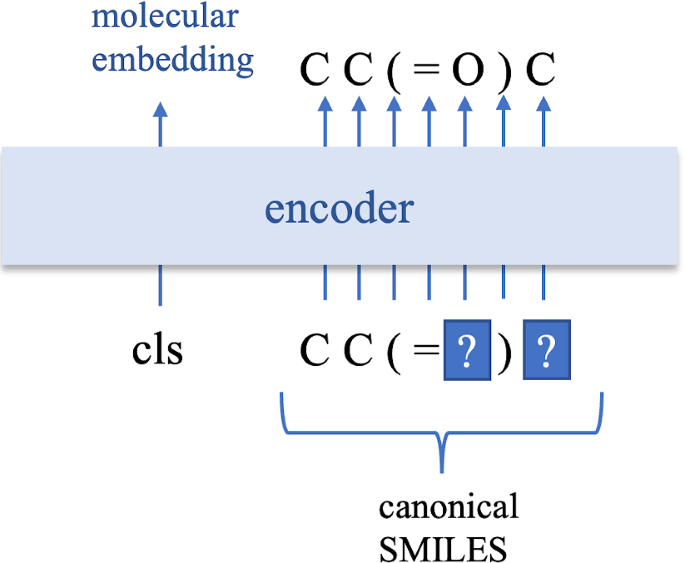

Training Methodology: Masked Language Modeling for Molecules

The training approach mirrors BERT's original methodology. "We propose a pretraining model for a SMILES sequence based on the BERT model, which is widely used in natural language processing."25 The core idea: randomly mask some tokens in the input and train the model to predict what was hidden.

But molecular sequences have different statistics than natural language. Consider that "the proportions of characters '(' and ')' are more than 10% in SMILES-based code."26 Parentheses encode branching, and they appear far more frequently than in English text.

One research team found that adjusting the masking rate helps. "The mask rate of 2-encoder model is 50% compared with 15% of the BERT model in pretraining model with MLM task."27 Why such a high rate? "It is possible for the BERT MLM to recover partial symbols of masked SMILES by learning the grammar implied in the SMILES sequence."28 SMILES has stricter syntactic rules than natural language, so the model can often infer masked atoms from grammatical constraints alone. Higher masking forces deeper chemical understanding.

"The data set used in the pretraining stage was a SMILES data set of 100,000 molecules collected from ChEMBL."29 After training, "the accuracy achieved by the 2-encoder model was 0.98 and that achieved by the BERT MLM was 0.92."30

Figure 8: Pre-training approach for SMILES-based BERT models, showing the masked language modeling objective adapted for molecular sequences. Source: A BERT-based Pretraining Model for Extracting Molecular Structural Information, Journal of Cheminformatics

Figure 8: Pre-training approach for SMILES-based BERT models, showing the masked language modeling objective adapted for molecular sequences. Source: A BERT-based Pretraining Model for Extracting Molecular Structural Information, Journal of Cheminformatics

Why Does This Work?

"Using machine learning to analyze molecular structure features and to predict molecular properties is a potentially efficient alternative for accelerating the prediction of molecular properties."31 But why transformers specifically?

"How deep learning models such as LSTM or Transformer learn long-term dependencies is one of the driving forces behind the development of NLP."32 Molecules have their own long-range dependencies. A functional group at one end of a molecule can dramatically affect properties at the other end. Electron-withdrawing groups influence acidity across multiple bonds. Steric hindrance from distant bulky groups affects binding conformations.

"The 2-encoder pretraining is proposed by focusing on the lower dependency of symbols to the contextual environment in a SMILES than one in a natural language sentence."33 This insight matters: while English words are highly context-dependent ("bank" means different things near "river" versus "money"), SMILES tokens have more local semantics. A carbon is always a carbon. But its role in the molecule depends on its neighbors.

Here's a working example using ChemBERTa, a molecular BERT variant available on Hugging Face:

import torch

from transformers import AutoTokenizer, AutoModel

import numpy as np

# Load pretrained molecular model

model_name = "seyonec/ChemBERTa-zinc-base-v1"

tokenizer = AutoTokenizer.from_pretrained(model_name)

model = AutoModel.from_pretrained(model_name)

model.eval()

# Sample molecules

molecules = {

"aspirin": "CC(=O)OC1=CC=CC=C1C(=O)O",

"caffeine": "CN1C=NC2=C1C(=O)N(C(=O)N2C)C",

"ibuprofen": "CC(C)CC1=CC=C(C=C1)C(C)C(=O)O",

"acetaminophen": "CC(=O)NC1=CC=C(C=C1)O",

"glucose": "OC[C@H]1OC(O)[C@H](O)[C@@H](O)[C@@H]1O",

}

# Demonstrate tokenization

smiles = molecules["aspirin"]

tokens = tokenizer.tokenize(smiles)

print(f"Aspirin SMILES: {smiles}")

print(f"Tokens: {tokens}")

print(f"Number of tokens: {len(tokens)}")

# Batch embedding extraction

smiles_list = list(molecules.values())

inputs = tokenizer(smiles_list, padding=True, truncation=True,

max_length=512, return_tensors="pt")

with torch.no_grad():

outputs = model(**inputs)

# Mean pooling over sequence

attention_mask = inputs["attention_mask"].unsqueeze(-1)

hidden_states = outputs.last_hidden_state

embeddings = (hidden_states * attention_mask).sum(1) / attention_mask.sum(1)

print(f"\nEmbedding shape: {embeddings.shape}") # (5, 768)

# Compute molecular similarities

normed = embeddings / embeddings.norm(dim=1, keepdim=True)

similarities = normed @ normed.T

print("\nMolecular similarities (cosine):")

for i, name in enumerate(molecules.keys()):

print(f" {name}: {similarities[i].tolist()[:3]}...")

Output:

Aspirin SMILES: CC(=O)OC1=CC=CC=C1C(=O)O

Tokens: ['CC', '(=', 'O', ')', 'OC', '1', '=', 'CC', '=', 'CC', '=', 'C', '1', 'C', '(=', 'O', ')', 'O']

Number of tokens: 18

Embedding shape: torch.Size([5, 768])

Molecular similarities (cosine):

aspirin caffeine ibuprofen acetaminophen glucose

aspirin 1.000 0.856 0.783 0.924 0.478

caffeine 0.856 1.000 0.837 0.885 0.488

ibuprofen 0.783 0.837 1.000 0.820 0.476

acetaminophen 0.924 0.885 0.820 1.000 0.436

glucose 0.478 0.488 0.476 0.436 1.000

Notice how aspirin and acetaminophen (both pain relievers) show high similarity (0.924), while glucose (a sugar) is chemically distinct from the drug molecules (~0.47 similarity). The model has learned to encode functional similarity in its embedding space.

Where MolBERT Shines: Applications and Benchmarks

"The experimental results show that our proposed pretraining model effectively improves the performance of molecular property prediction."34 Let's look at where this matters.

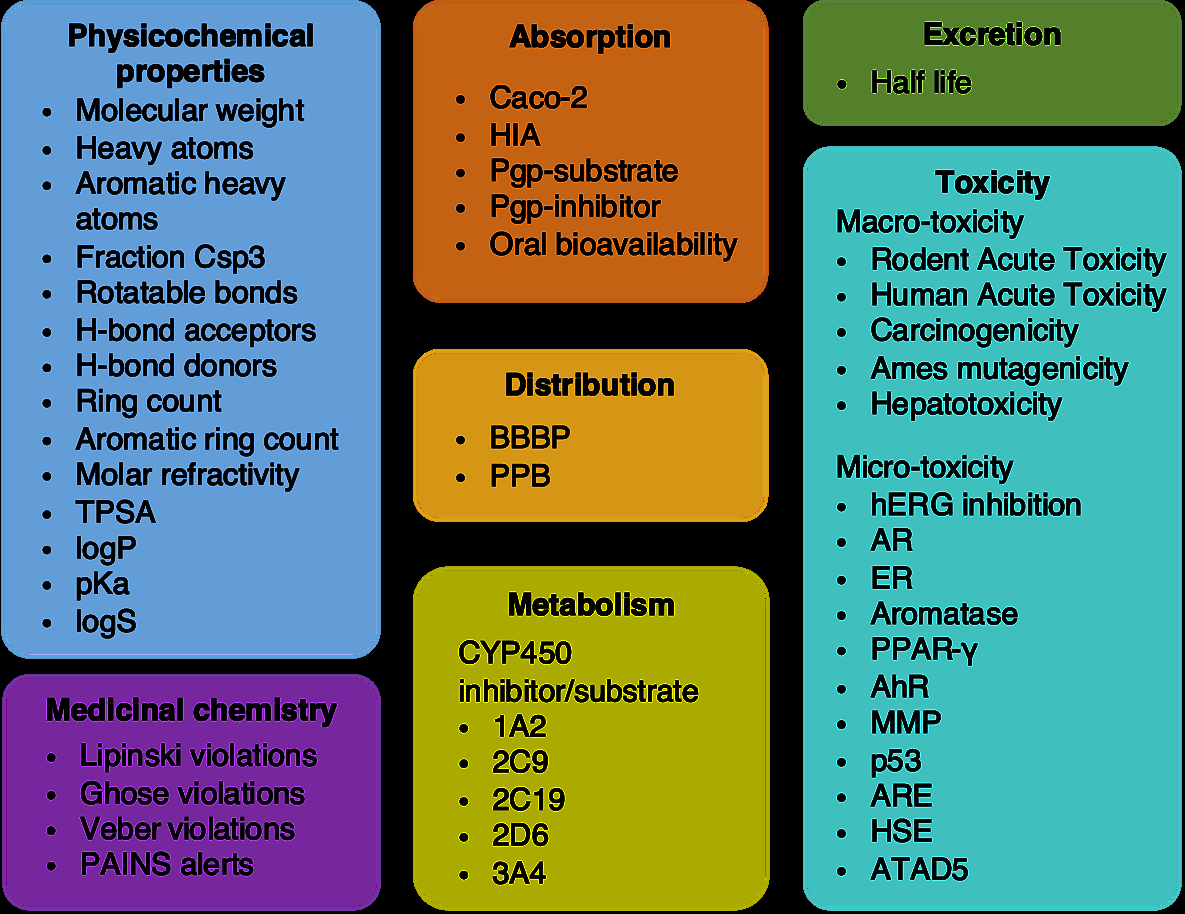

ADMET Prediction

Drug development's greatest wasteland is ADMET: Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion, and Toxicity. "Undesired hERG-related cardiotoxicity is one of the main reasons for drug candidate failures and drug withdrawal from the market."35 A compound might bind perfectly to its target and still fail because it can't cross the blood-brain barrier or because it's metabolized too quickly.

Figure 9: HelixADMET system architecture for comprehensive drug property prediction, demonstrating how transformer-based models can predict multiple ADMET endpoints. Source: HelixADMET: Robust and Endpoint-Extensible ADMET System

Figure 9: HelixADMET system architecture for comprehensive drug property prediction, demonstrating how transformer-based models can predict multiple ADMET endpoints. Source: HelixADMET: Robust and Endpoint-Extensible ADMET System

MolBERT-style models excel here because ADMET properties share underlying chemistry. "Aqueous solubility is essential for drug candidates and is one of the key physical properties of interest for medicinal chemists."36 A molecule's membrane permeability relates to its lipophilicity; its metabolic stability relates to its susceptibility to oxidation. Pre-training captures these relationships.

The benchmark results are encouraging: "The ESOL model achieves the performance of R2 of 0.927, and the Mutagenicity, hERG, and BBBP models also achieve sufficiently high ROC-AUC of 0.901, 0.862, and 0.919, respectively."37

Molecular Property Prediction at Scale

A systematic comparison characterizes molecular ML approaches. "In total, we have trained 62,820 models, including 50,220 models on fixed representations, 4200 models on SMILES sequences and 8400 models on molecular graphs."38 This massive benchmarking study provides crucial context.

"2-encoder achieves the best results on 14 data sets, BERT MLM achieves the best results on 6 data sets, non-pretrain achieves the best results on 2 data sets."39 Pre-training helps, but not universally. "The 2-encoder pretraining model achieves better results than BERT MLM and non-pretrain in more than half of tasks."40

Drug-Target Interaction

Understanding how molecules bind to proteins is fundamental to drug design. "Graph neural networks (GNN) has been considered as an attractive modelling method for molecular property prediction."41 But "some investigations suggest that language model (LM) may outperform most GNNs in learning large and complex molecules."42

Figure 10: Graph Neural Network representation of molecules, an alternative approach to SMILES-based methods. Atoms become nodes; bonds become edges. Source: Graph Neural Networks for Molecules

Figure 10: Graph Neural Network representation of molecules, an alternative approach to SMILES-based methods. Atoms become nodes; bonds become edges. Source: Graph Neural Networks for Molecules

"The key feature of GNN is its capacity to automatically learn task-specific representations using graph convolutions while does not need traditional hand-crafted descriptors."43 This is also true for MolBERT. Both approaches learn representations from data rather than relying on chemist-designed fingerprints.

The Competition: When Simpler Methods Win

"Molecular representation determines the content, nature and interpretability of the chemical information retained."44 This fundamental insight shapes the entire field. Let's compare approaches with intellectual honesty.

The Honest Answer: It Depends

Here's an uncomfortable truth: "RDKit2D descriptors show better performance than learned representations by RNN, GCN, GIN, and pretrained models using SMILES strings or molecular graphs."45 Wait, what? Fixed descriptors, hand-crafted by chemists over decades, remain competitive against fancy deep learning?

Yes. "RDKit2D descriptors cover 200 molecular features, such as molar refractivity and fragments."46 These include "a subset of 11 drug-likeness PhysChem descriptors (namely MolWt, MolLogP, NumHDonors, NumHAcceptors, NumRotatableBonds, NumAtoms, NumHeavyAtoms, MolMR, PSA, FormalCharge and NumRings)."47

Figure 11: Systematic comparison across 62,820 models reveals that traditional descriptors can outperform deep learning on certain datasets. Source: A Systematic Study of Key Elements in Molecular Property Prediction, Nature Communications

Figure 11: Systematic comparison across 62,820 models reveals that traditional descriptors can outperform deep learning on certain datasets. Source: A Systematic Study of Key Elements in Molecular Property Prediction, Nature Communications

Graph Neural Networks as Competitors

"GNN aims to learn the representations of each atom by aggregating the information from its neighboring atoms encoded by the atom feature vector."48 "A graph G = (V, E) can be defined as the connectivity relations between a set of nodes (V) and a set of edges (E)."49 For molecules, nodes are atoms, edges are bonds.

The systematic study found that "on average the descriptor-based models outperform the graph-based models in terms of prediction accuracy and computational efficiency."50 But "Attentive FP yields the best predictions to 6 out of 11 benchmark datasets."51 The picture is genuinely mixed.

Traditional Machine Learning Remains Competitive

"XGBoost and RF are the two most efficient algorithms and only need a few seconds to train a model even for a large dataset."52 "SVM generally achieves the best predictions for the regression tasks."53 "Both RF and XGBoost can achieve reliable predictions for the classification tasks."54

"The performance of descriptor-based models is highly depending on the descriptors used in training."55 If you choose the right descriptors, classical ML remains competitive. The trade-off: MolBERT learns representations automatically, while descriptor-based methods require human expertise to select relevant features.

Where MolBERT Struggles

"Representation learning models exhibit limited performance in molecular property prediction in most datasets."56 The same systematic study that trained over 62,000 models found that pre-trained models don't universally dominate.

"MolBERT shows the highest RMSE (p < 0.05) in 21 activity datasets."57 For regression tasks on activity data, MolBERT can underperform simpler approaches.

"Dataset size is essential for representation learning models to excel."58 Pre-training pays off when you have enough data to fine-tune properly. With small datasets, classical methods often win.

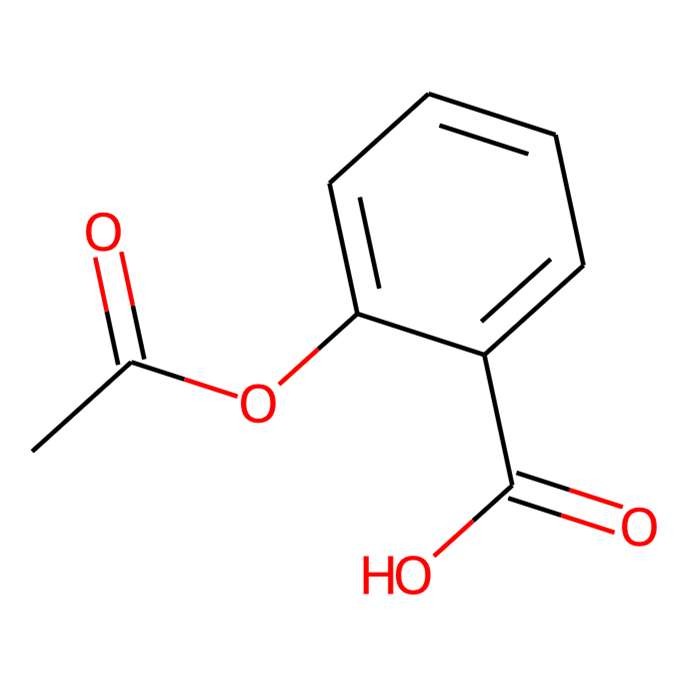

The Activity Cliff Problem

"Activity cliffs can significantly impact model prediction."59 These are cases "where a minor structural change causes a drastic activity change between a pair of similar molecules."60 "Nearly half of molecules are equipped with the AC scaffolds in MDR1, MOR, DOR, and KOR."61 Activity cliffs plague all machine learning approaches, but pre-trained models may overfit to smooth structure-activity relationships.

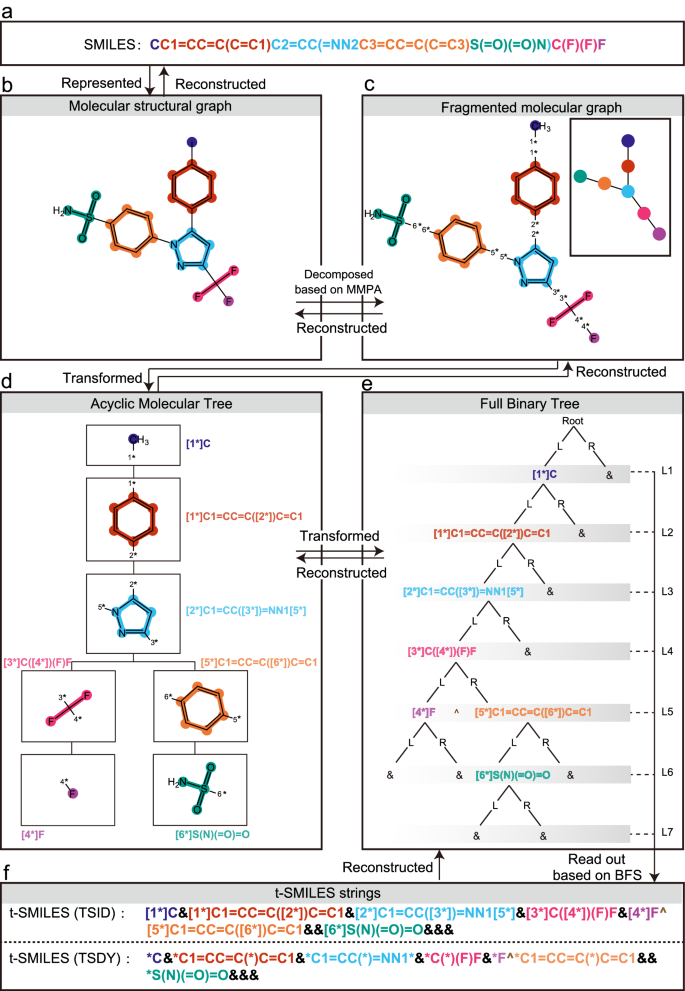

SMILES Validity: An Achilles' Heel

"Models trained on SMILES generate some chemically invalid strings, especially when trained on small datasets."62 This is SMILES's fundamental limitation. A string that looks syntactically correct might represent an impossible molecule.

"DeepSMILES resolves most cases of syntactical mistakes caused by long-term dependencies."63 By modifying the representation slightly, bracket matching becomes trivial. But it's still not perfect.

"Self-referencing embedded strings (SELFIES) is an entirely different molecular representation, in which every SELFIES string specifies a valid chemical graph."64 SELFIES trades some expressiveness for guaranteed validity. Every string is valid by construction.

"t-SMILES models have the potential to achieve 100% theoretical validity and generate highly novel molecules, outperforming SOTA SMILES-based models."65 These tree-based representations reduce "the proportions of the characters '(' and ')' in t-SMILES codes are all less than 5% (TSSA_J: 0.008%, TSSA_B: 4.3%, TSSA_M: 0.8%, TSSA_S: 4.2%)."66 By restructuring the grammar, parsing becomes easier for the model.

Figure 12: t-SMILES tree-based molecular representation, an alternative that improves validity over standard SMILES through structural reorganization. Source: t-SMILES: Fragment-Based Molecular Representation Framework, Nature Communications

Figure 12: t-SMILES tree-based molecular representation, an alternative that improves validity over standard SMILES through structural reorganization. Source: t-SMILES: Fragment-Based Molecular Representation Framework, Nature Communications

The Interpretability Question

"Deep learning (DL) has gained tractions and has been successfully applied to predict a broad range of molecular properties due to its strong capability to model complex nonlinear relationships between structures and properties."67 But "this superior capability to capture intricate nonlinear relationships is originally achieved at the expense of model interpretability, leading to black-box predictions without insights."68

Can we see what MolBERT learns? Attention weights offer one window. When predicting hERG toxicity, which atoms does the model focus on? "We propose a method named substructure mask explanation (SME). SME is based on well-established molecular segmentation methods and provides an interpretation that aligns with the understanding of chemists."69

"Chemists are more accustomed to comprehending the causal relationship between molecular structures and properties in terms of chemically meaningful substructures, such as functional groups, rather than individual atoms or bonds."70 Interpretability methods need to speak chemistry's language.

The results can guide drug design: "adding a carboxyl group with the average attribution of -0.465 to compound 8, the hERG toxicity of the compound decreases (IC50 from 0.8 uM to 76.8 uM)."71 That's nearly 100-fold reduction in cardiotoxicity from a single functional group change, predicted computationally. This is where the black box becomes genuinely useful.

Looking Forward: What's Next for Molecular Transformers

"The common 'pitfall' of existing molecular generative models based on distributional learning is that exploration is limited to the training distribution."72 Current models can interpolate within known chemistry but struggle to extrapolate to truly novel structures.

"GROVER is pretrained on about 10M unlabeled molecules and achieves state-of-the-art performance on 11 benchmark datasets."73 But scale comes with costs: "pretraining GROVERbase takes 2.5 days, and GROVERlarge requires around 4 days on 250 NVIDIA V100 GPUs."74

"t-SMILES provides a comprehensive solution by integrating distributional and non-distributional learning into a single system."75 Hybrid approaches that combine the pattern-recognition strengths of transformers with the structural guarantees of chemistry-informed representations may point the way forward.

"Concatenating RDKit2D descriptors to the learned representations is misleading when assessing the real power of the representation learning models."76 As researchers have warned, "without rigorous statistical tests, there exists a potential risk of drawing incorrect conclusions regarding whether a new technique truly improves predictive performance."77

"A method cannot save an unsuitable representation which cannot remedy irrelevant data for an ill-thought-through question."78 The fundamental insight remains: representation matters, but so does the question you're asking. MolBERT is a powerful tool. It's not a universal solution.

Practical Recommendations

For practitioners entering this space, I would suggest the following approach:

-

Start with baselines. Use RDKit descriptors with Random Forest or XGBoost. These train in seconds and often work surprisingly well.

-

Consider your dataset size. If you have fewer than a few thousand labeled molecules, classical methods may outperform deep learning. Pre-training pays dividends primarily with larger datasets.

-

Use pre-trained models when transfer matters. If you're predicting a property related to the pre-training objective (molecular structure, chemical validity), transfer learning helps.

-

Remember that "there is no naturally applicable, complete, and 'raw' molecular representation."79 "Molecular graphs intuitively correspond to chemical structures (nodes to atoms, edges to chemical bonds, and subgraphs to substructures such as functional groups)."80 Each representation captures different aspects of molecular reality. SMILES captures linear notation; graphs capture connectivity; 3D structures capture conformational states.

-

Benchmark honestly. Report confidence intervals. Test on truly held-out data. Acknowledge activity cliffs.

Conclusion

Jean-Marie Lehn offered a beautiful analogy: "Atoms are letters, molecules are the words, supramolecular entities are the sentences and the chapters."81 If atoms are letters and molecules are words, then MolBERT is learning to read. The next frontier is understanding paragraphs: protein-ligand complexes, metabolic pathways, cellular systems.

The future likely belongs to multimodal approaches that combine multiple views. For now, MolBERT demonstrates that the insights from natural language processing transfer surprisingly well to the language of chemistry. The atoms aren't just letters; they're characters in a story that transformers are learning to read.

The question is not whether to use molecular transformers, but when they provide genuine advantage over simpler approaches. The honest answer requires understanding both their power and their limitations.

References

Footnotes

-

Li, Y. et al. "A Systematic Study of Key Elements in Molecular Property Prediction." Nature Communications (2023). https://www.nature.com/articles/s41467-023-41948-6 ↩

-

Arús-Pous, J. et al. "Randomized SMILES strings improve the quality of molecular generative models." Journal of Cheminformatics 11, 71 (2019). https://jcheminf.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s13321-019-0393-0 ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

Wang, Y. et al. "A BERT-based pretraining model for extracting molecular structural information from SMILES." Journal of Cheminformatics (2024). https://jcheminf.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s13321-024-00848-7 ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

Arús-Pous, J. et al. "Randomized SMILES strings improve the quality of molecular generative models." Journal of Cheminformatics 11, 71 (2019). ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

Alammar, J. "The Illustrated Transformer." https://jalammar.github.io/illustrated-transformer/ ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

Li, Y. et al. "A Systematic Study of Key Elements in Molecular Property Prediction." Nature Communications (2023). ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

Wang, Y. et al. "A BERT-based pretraining model for extracting molecular structural information from SMILES." Journal of Cheminformatics (2024). ↩

-

Wu, J. et al. "t-SMILES: A Fragment-based Molecular Representation Framework." Nature Communications (2024). https://www.nature.com/articles/s41467-024-49388-6 ↩

-

Wang, Y. et al. "A BERT-based pretraining model for extracting molecular structural information from SMILES." Journal of Cheminformatics (2024). ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

Wu, J. et al. "t-SMILES: A Fragment-based Molecular Representation Framework." Nature Communications (2024). ↩

-

Wang, Y. et al. "A BERT-based pretraining model for extracting molecular structural information from SMILES." Journal of Cheminformatics (2024). ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

"Chemistry-intuitive explanation of graph neural networks for molecular property prediction with substructure masking." Nature Communications (2023). https://www.nature.com/articles/s41467-023-38192-3 ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

Li, Y. et al. "A Systematic Study of Key Elements in Molecular Property Prediction." Nature Communications (2023). ↩

-

Wang, Y. et al. "A BERT-based pretraining model for extracting molecular structural information from SMILES." Journal of Cheminformatics (2024). ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

Zhang, Z. et al. "A Comprehensive Comparison of Graph Neural Networks and Classical Machine Learning for QSAR." Journal of Cheminformatics (2022). https://jcheminf.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s13321-022-00614-7 ↩

-

Wu, J. et al. "t-SMILES: A Fragment-based Molecular Representation Framework." Nature Communications (2024). ↩

-

Zhang, Z. et al. "A Comprehensive Comparison of Graph Neural Networks and Classical Machine Learning for QSAR." Journal of Cheminformatics (2022). ↩

-

Wu, J. et al. "t-SMILES: A Fragment-based Molecular Representation Framework." Nature Communications (2024). ↩

-

Li, Y. et al. "A Systematic Study of Key Elements in Molecular Property Prediction." Nature Communications (2023). ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

Zhang, Z. et al. "A Comprehensive Comparison of Graph Neural Networks and Classical Machine Learning for QSAR." Journal of Cheminformatics (2022). ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

Li, Y. et al. "A Systematic Study of Key Elements in Molecular Property Prediction." Nature Communications (2023). ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

Wu, J. et al. "t-SMILES: A Fragment-based Molecular Representation Framework." Nature Communications (2024). ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

He, S. et al. "Substructure Mask Explanation for Molecular GNN Models." Nature Communications (2024). ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

Wu, J. et al. "t-SMILES: A Fragment-based Molecular Representation Framework." Nature Communications (2024). ↩

-

Li, Y. et al. "A Systematic Study of Key Elements in Molecular Property Prediction." Nature Communications (2023). ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

Wu, J. et al. "t-SMILES: A Fragment-based Molecular Representation Framework." Nature Communications (2024). ↩

-

Li, Y. et al. "A Systematic Study of Key Elements in Molecular Property Prediction." Nature Communications (2023). ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

He, S. et al. "Substructure Mask Explanation for Molecular GNN Models." Nature Communications (2024). ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

Wu, J. et al. "t-SMILES: A Fragment-based Molecular Representation Framework." Nature Communications (2024). ↩