Making Science Machine-Readable: The Epistemological Challenge of Verifying Knowledge at Scale

Here is a question that keeps me up at night: how do you verify scientific knowledge when there are 2.9 million papers on arXiv alone, with thousands more added every day?1

Human peer review worked when Einstein submitted his gravitational waves paper in 1936. Howard Percy Robertson wrote a 10-page referee report identifying errors in Einstein's non-existence proof. Robertson showed that recasting the Einstein-Rosen metric in cylindrical coordinates removed the problematic singularities. The paper was eventually revised and published.2 This is peer review at its finest: expert humans catching expert mistakes before publication.

But Robertson reviewed one paper. What happens when there are 50,000 new papers every month across preprint servers?3 What happens when no single human can read even a fraction of the relevant literature in their own subfield? The scientific enterprise has outgrown its verification infrastructure.

A new paper from Booeshaghi, Luebbert, and Pachter asks whether we can build systems that help.4 Their answer involves extracting nearly two million claims from 16,087 manuscripts and comparing machine evaluation to human peer review. The results are striking: 81% agreement. But the deeper question their work raises is philosophical: what does it mean for a machine to "verify" a scientific claim?

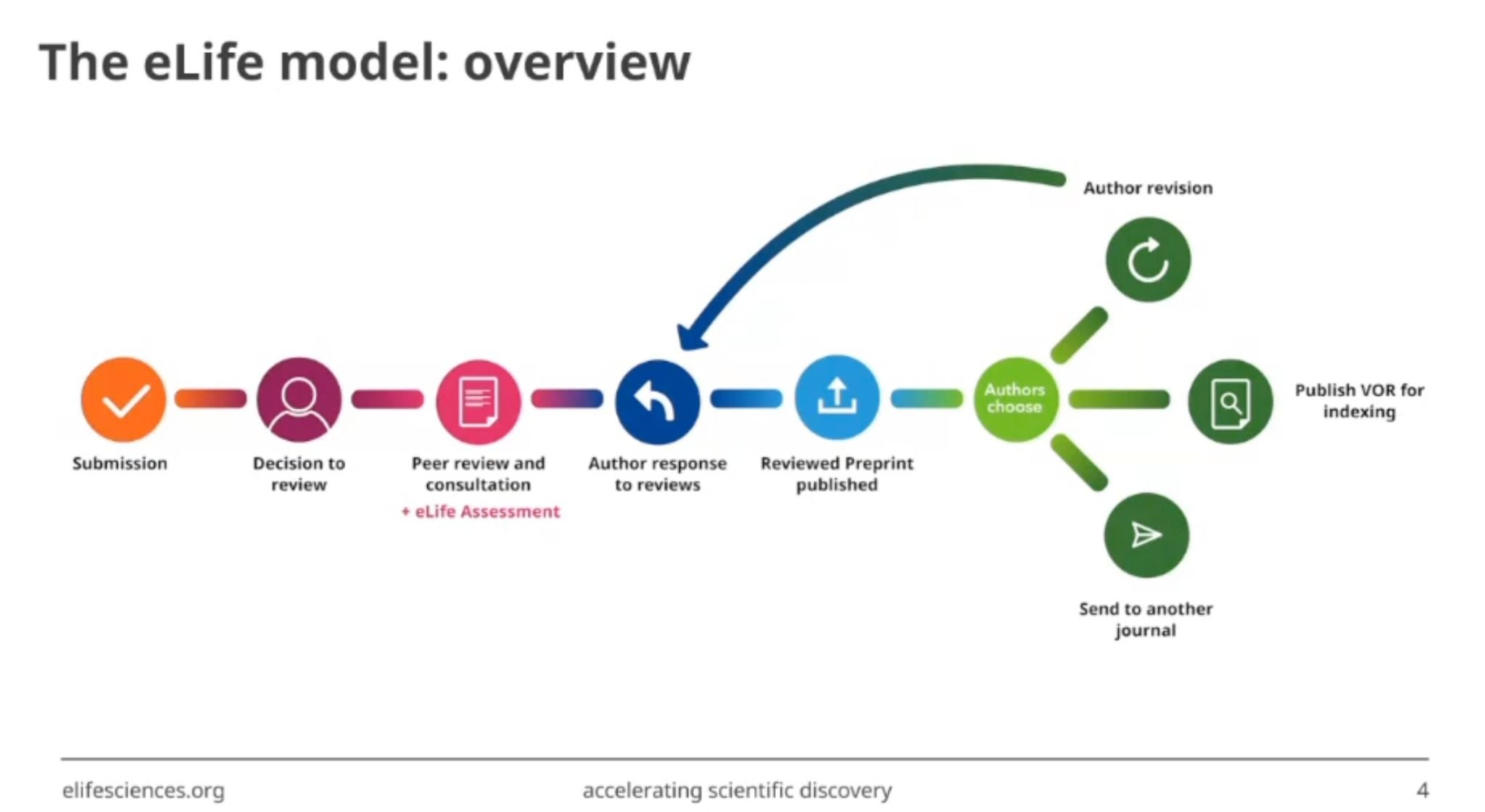

Figure 1: The eLife publishing model workflow, showing how manuscripts move through peer review and become machine-readable records. Source: Booeshaghi et al., "Science should be machine-readable"4

Figure 1: The eLife publishing model workflow, showing how manuscripts move through peer review and become machine-readable records. Source: Booeshaghi et al., "Science should be machine-readable"4

The Semantic Web Dream (And Why It Partially Failed)

This is not the first attempt to make knowledge machine-readable. Tim Berners-Lee's semantic web vision, crystallized in the early 2000s, proposed that all web content could be structured as machine-processable data. The core technology was the Resource Description Framework (RDF): a framework for representing information as subject-predicate-object triples, where elements could be IRIs, blank nodes, or datatyped literals.5

The idea was elegant. Instead of documents that only humans could read, the web would become a vast knowledge graph where machines could traverse relationships, make inferences, and answer questions. The W3C published recommendations. Ontology languages like OWL emerged. SPARQL query languages allowed machines to interrogate knowledge bases.

And then... partial adoption, at best.

The Google Knowledge Graph, announced in 2012, brought the phrase "knowledge graph" into mainstream tech discourse.6 Companies followed: Airbnb, Amazon, eBay, Facebook, IBM, LinkedIn, Microsoft, Uber, and others built enterprise knowledge graphs for specific applications.7 Wikidata, the largest open knowledge base, grew to cover millions of entities, collecting structured data under the Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication 1.0.8

But the grand vision of a machine-readable web never materialized. Why not?

The challenge was not technical. It was sociological.9 Defining shared meanings across domains turned out to be harder than building the infrastructure. Scientific vocabulary is domain-specific, often hard-to-parse, and evolves constantly. Getting researchers to agree on formal definitions of even basic concepts proved nearly impossible. RDF and OWL were too complex for most applications. Simpler graph structures like property graphs gained more traction because they traded formal rigor for practical usability.

The semantic web taught us that you cannot impose machine-readability from the top down. But perhaps you can extract it from the bottom up.

What LLMs Changed

Large language models shifted the equation. Unlike the semantic web, which required everyone to agree on schemas upfront, LLMs can parse natural language directly. The structured data does not need to exist beforehand. You can extract it from prose.

As the researchers put it: "LLMs are general-purpose parsers of natural language. Any scientific artifact that can be represented as text, papers, code, methods, and reviews, can be ingested, transformed, and reorganized by an LLM."10

The OpenEval system demonstrates this approach. Instead of requiring scientists to write in a formal language, it extracts structured claims from ordinary scientific papers. Using Claude Sonnet 4.5, it processes manuscripts through a five-stage pipeline:11

- Extraction: Extract atomic, factual claims from the manuscript text

- Grouping: Group those claims into research results

- Machine Evaluation: Have the LLM evaluate each result

- Peer Review Interpretation: Extract evaluations from human peer review commentary

- Comparison: Compare the two sets of evaluations

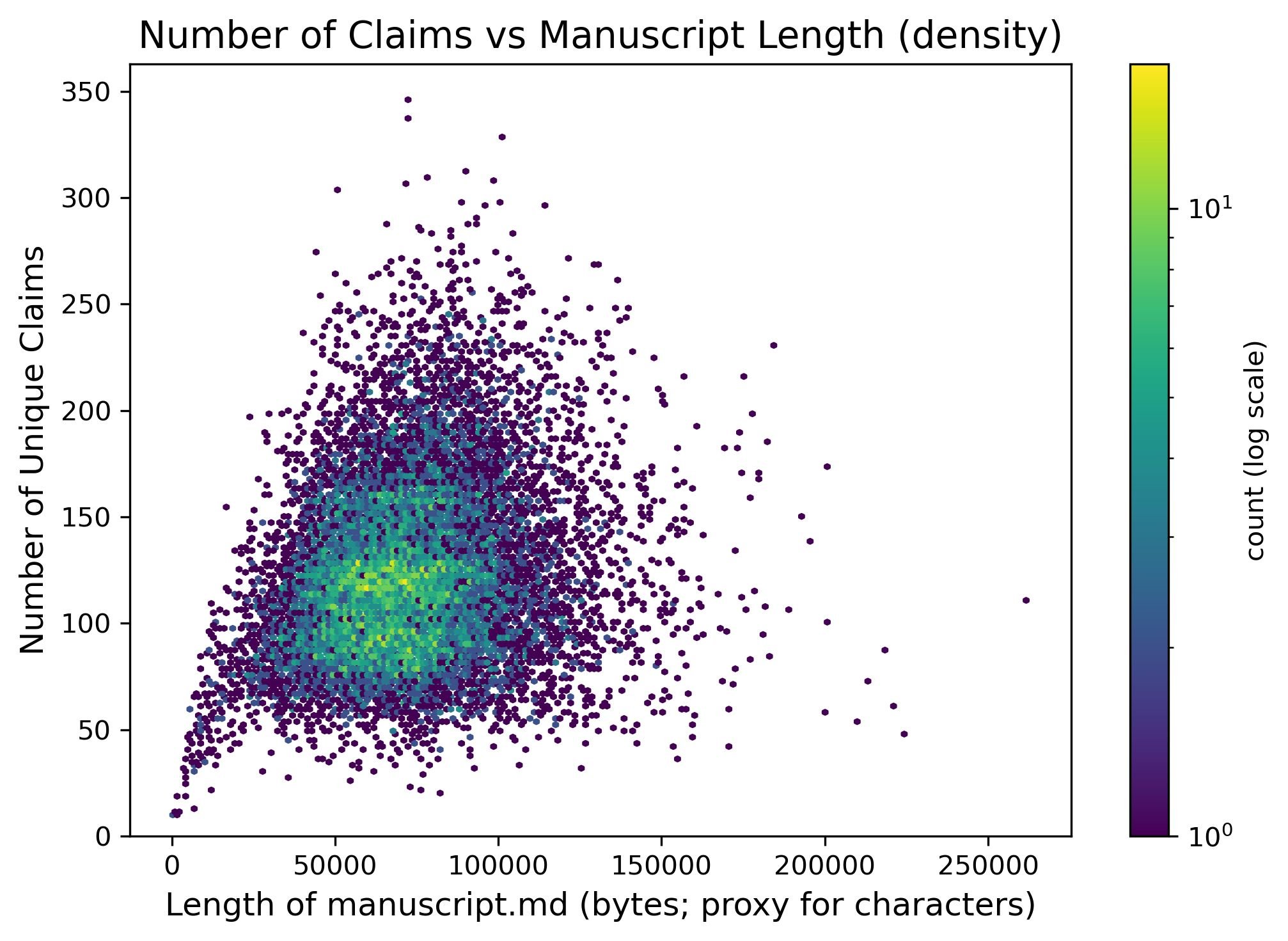

From 16,087 eLife manuscripts, OpenEval extracted 1,964,602 claims, approximately 112 claims per paper.12 These claims were grouped into 298,817 results. Each claim is a literal excerpt that can be traced back to the original text.13

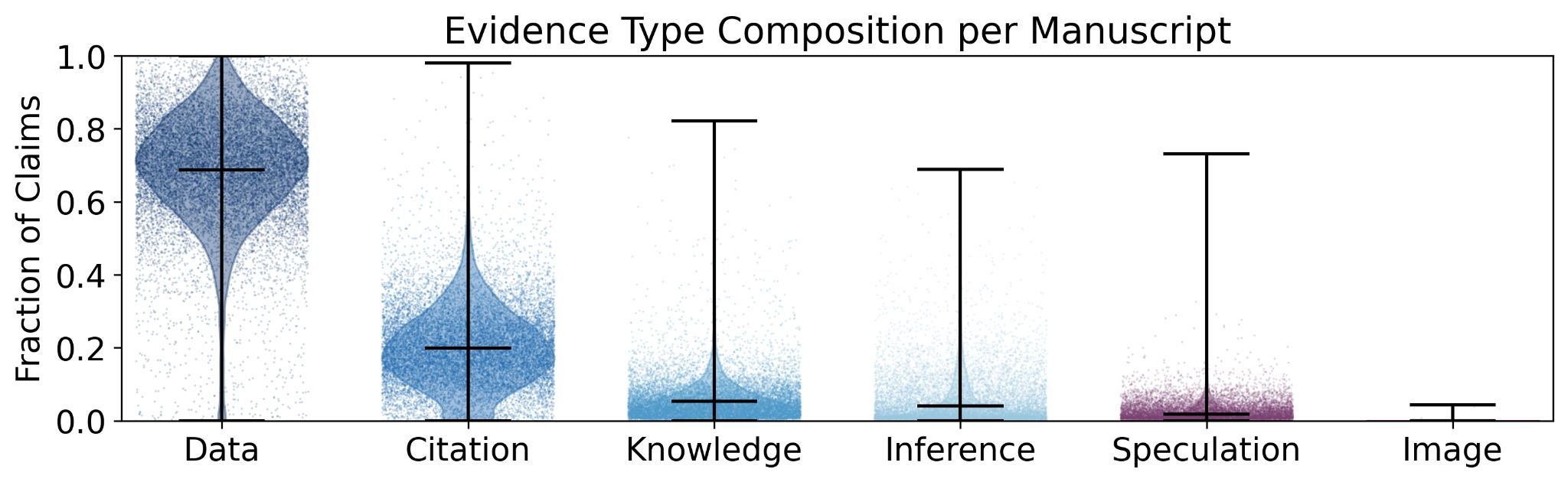

Figure 2: Evidence type composition per manuscript. Data-based claims (green) dominate scientific manuscripts, accounting for roughly 75% of all evidence types. Citations follow at approximately 20% and explicit knowledge claims at around 10%. Source: Booeshaghi et al.14

Figure 2: Evidence type composition per manuscript. Data-based claims (green) dominate scientific manuscripts, accounting for roughly 75% of all evidence types. Citations follow at approximately 20% and explicit knowledge claims at around 10%. Source: Booeshaghi et al.14

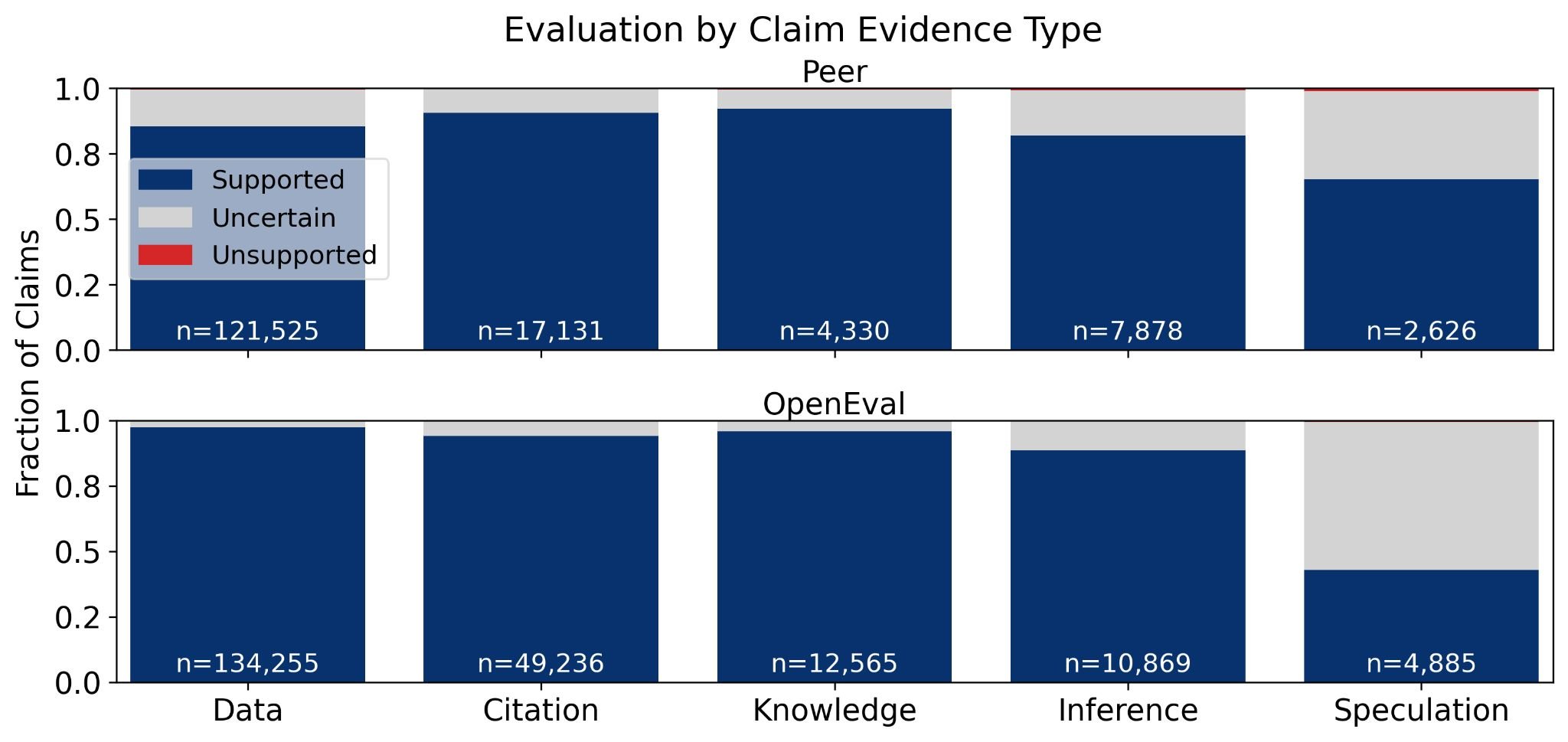

What kinds of claims are scientists making? Across manuscripts, data accounted for approximately 75% of all evidence types, followed by citations at roughly 20% and explicit knowledge claims at 10%.14 This distribution was consistent across manuscripts, suggesting a strong reliance on empirical and referenced support in scientific writing.

The evidence type matters for evaluation outcomes. Explicit claims were overwhelmingly supported by data and citations, while implicit claims showed a shift toward inference and speculation.15 Results backed by data or citations were most often marked as supported by both systems.

Figure 3: Evaluation outcomes by evidence type. Data-based claims show the highest support rates, while inference and speculation correlate with uncertainty. Source: Booeshaghi et al.

Figure 3: Evaluation outcomes by evidence type. Data-based claims show the highest support rates, while inference and speculation correlate with uncertainty. Source: Booeshaghi et al.

The Agreement Problem

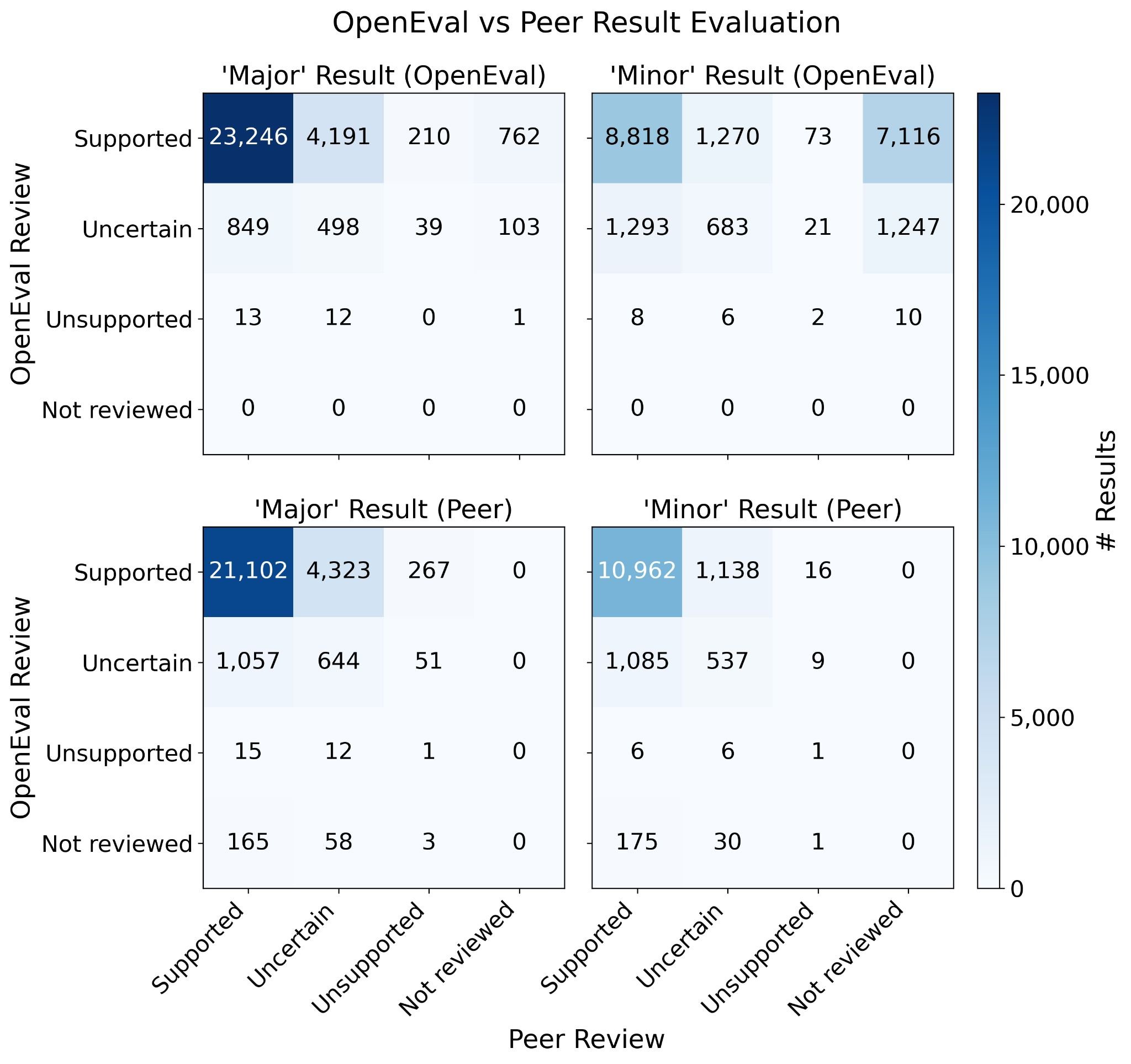

Here is the central empirical finding: OpenEval and human reviewers agreed on most research results.

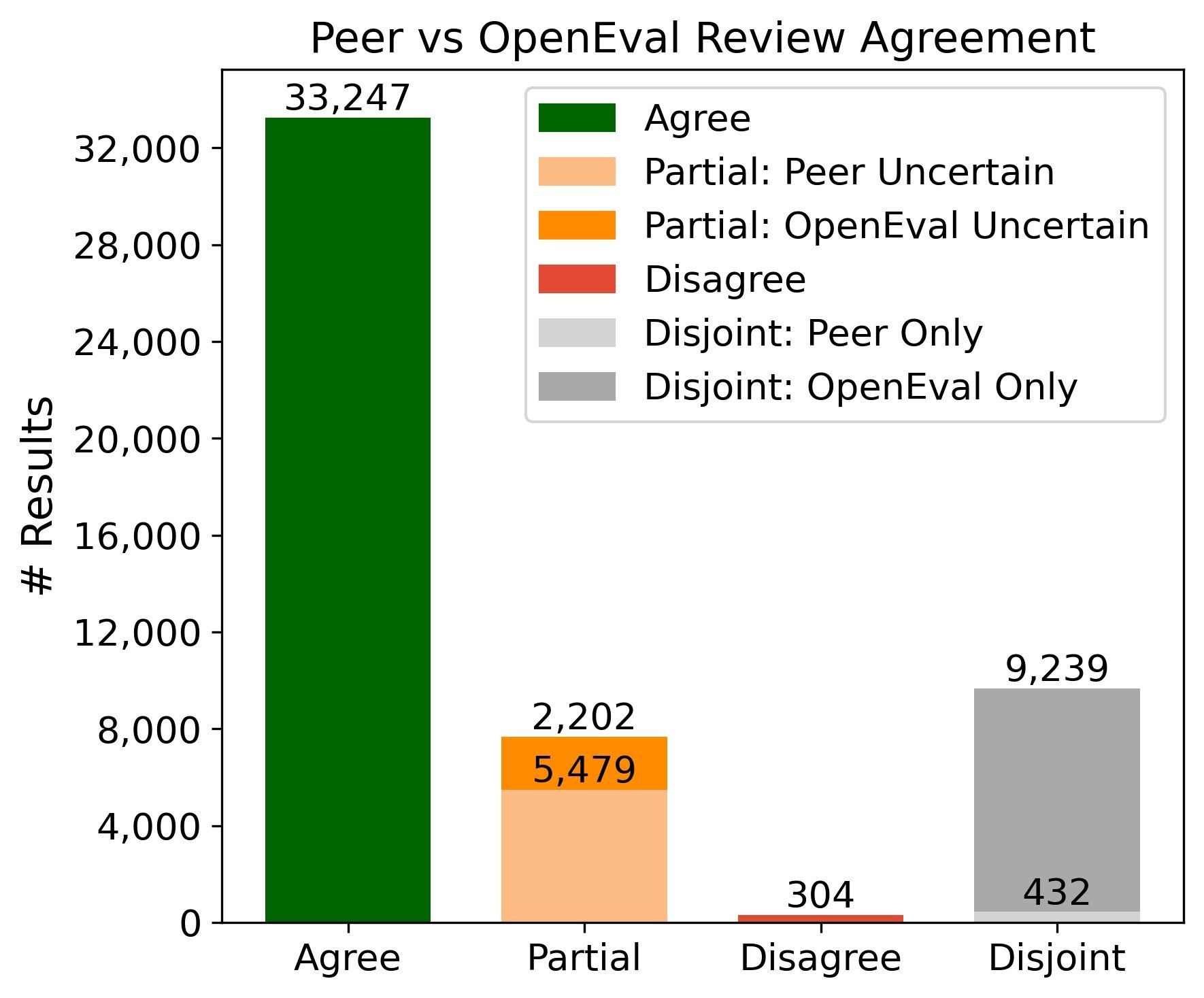

Of the 41,232 results evaluated by both systems, 33,247 (81%) received matching assessments. In 7,681 cases (19%), the evaluations partially agreed. Outright disagreement was rare, occurring in only 304 cases (0.7%).16

Figure 4: The majority of results (33,247) show complete agreement between human peer review and automated OpenEval. Outright disagreement is rare (304 cases). Source: Booeshaghi et al.

Figure 4: The majority of results (33,247) show complete agreement between human peer review and automated OpenEval. Outright disagreement is rare (304 cases). Source: Booeshaghi et al.

This 81% agreement rate sounds impressive. But what does it actually mean?

The cynical interpretation: both systems are agreeing that published, peer-reviewed papers are mostly supported by their evidence. That is not a surprise. The papers already passed peer review to be published. Only 0.09% of results were marked unsupported by OpenEval in its review of the entire corpus.17 This is expected for work that has already been vetted by humans.

The more interesting interpretation: the systems differ in coverage. OpenEval assessed 92.8% of research claims in a manuscript on average, while human reviewers were more selective, assessing only 68.1% of claims on average.18 Human reviewers have limited time and attention. They focus on what seems most important. The machine examines everything.

OpenEval found 866 major and 8,373 minor results that peer reviewers did not address. Some of these were evaluated as "Uncertain" or "Unsupported" by the machine.19 The machine is more thorough but less discriminating. Human reviewers focus on what they judge to be important. The machine reads everything.

Figure 5: Detailed confusion matrices comparing OpenEval and peer review classifications. Most results fall on the diagonal (agreement). Source: Booeshaghi et al.

Figure 5: Detailed confusion matrices comparing OpenEval and peer review classifications. Most results fall on the diagonal (agreement). Source: Booeshaghi et al.

Stability Over Time

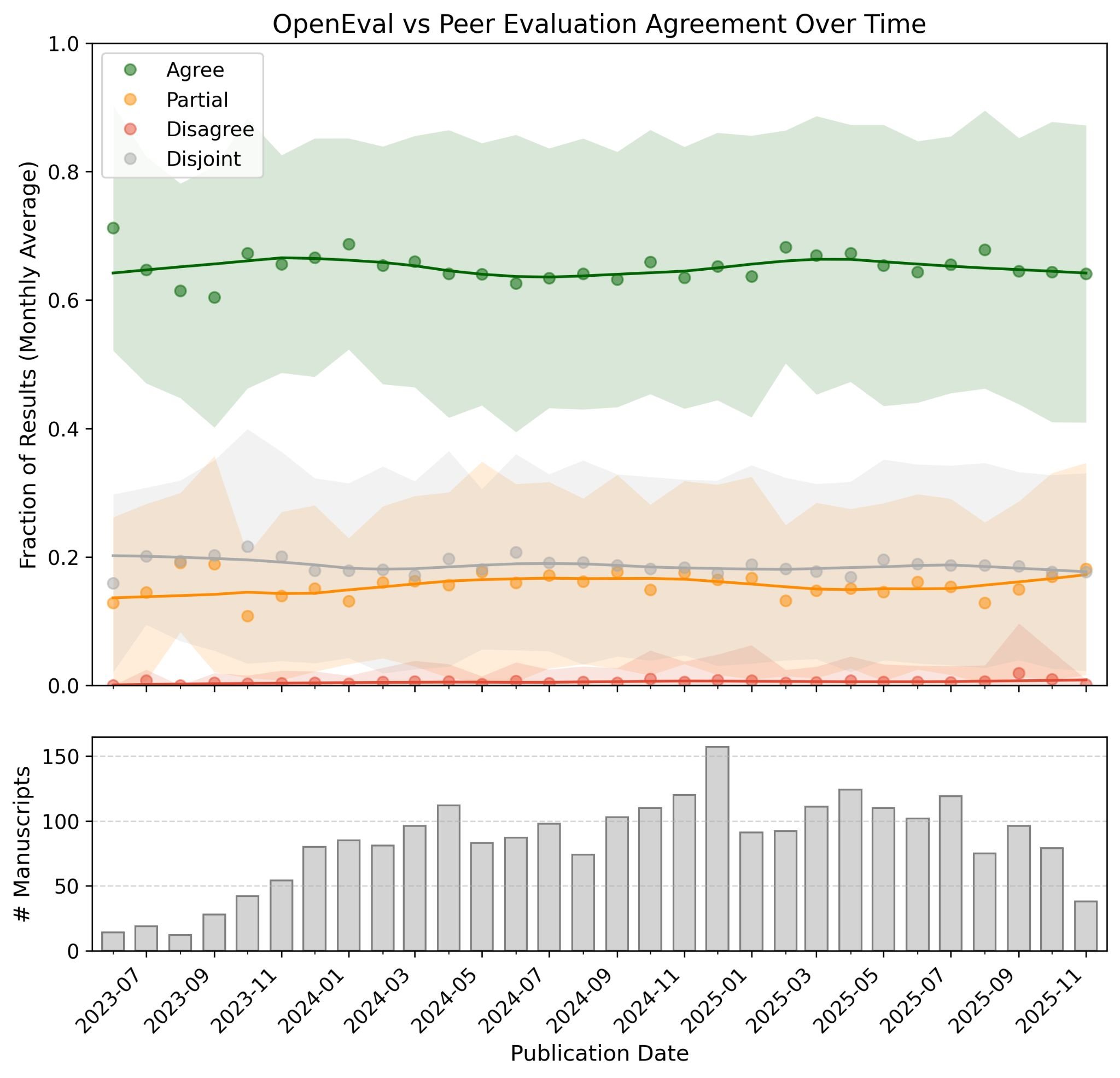

A reasonable worry about any AI system: is it stable? Do evaluation patterns drift as language models change or as editorial practices evolve?

The data suggests stability. Evaluation and agreement patterns remained stable over time. The proportion of matching assessments did not change meaningfully across publication dates.20

Figure 6: Agreement between OpenEval and peer review remains stable at approximately 65% over the studied period (2023-2025). The time series shows high variability month-to-month, likely due to variability in peer judgments, but no systematic drift. Source: Booeshaghi et al.

Figure 6: Agreement between OpenEval and peer review remains stable at approximately 65% over the studied period (2023-2025). The time series shows high variability month-to-month, likely due to variability in peer judgments, but no systematic drift. Source: Booeshaghi et al.

This matters because it suggests the system is measuring something real, not just fitting to quirks of particular papers or reviewers. If agreement drifted over time, you might worry about dataset artifacts. Stability suggests the machine and human evaluators are responding to similar underlying features of scientific evidence.

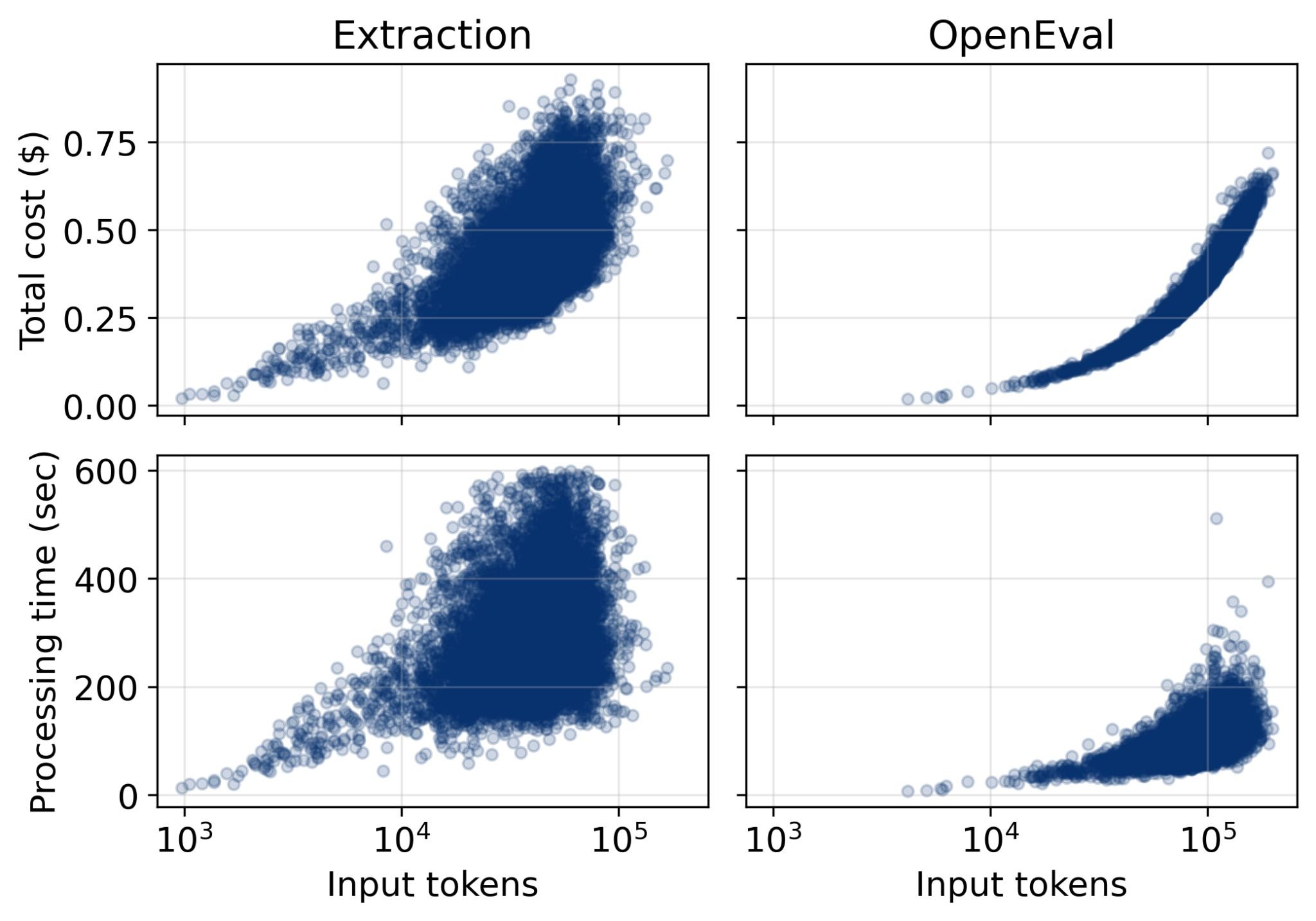

The Economics of Verification

Peer review is expensive. Reviewers donate their time. Journals spend money on editorial infrastructure. Nature charges up to $12,690 per paper in author fees.21 The process takes months.

What does machine review cost?

Extracting claims from the entire eLife corpus cost $6,844.77 total, or $0.43 per manuscript. Evaluation with OpenEval cost $5,287.94, or $0.33 per manuscript.22 Total processing time was 1,252.9 hours for claim extraction (280.38 seconds per manuscript) and 422.7 hours for evaluation (94.58 seconds per manuscript).23

Figure 7: OpenEval processing costs scale linearly with document length. Typical papers cost under $0.76 total for extraction plus evaluation. Source: Booeshaghi et al.

Figure 7: OpenEval processing costs scale linearly with document length. Typical papers cost under $0.76 total for extraction plus evaluation. Source: Booeshaghi et al.

Under a dollar per paper. Five minutes of processing time. At this cost, you could evaluate every paper on bioRxiv (over 389,000 papers) for under $300,000.1 arXiv's 2.9 million papers would cost roughly $2.2 million to process.

These numbers change the economics of scientific verification. They do not change the epistemology.

Connecting Results Across Papers

The most intriguing capability is not evaluation but connection. When results are represented as structured data, you can find relationships that citation graphs miss.

The researchers embedded all 298,817 extracted results using a text embedding model (OpenAI text-embedding-3-large) and constructed a k-Nearest-Neighbor graph to identify pairs of related results from different papers.24

This revealed several distinct classes of connections:25

Trivial pairs reflected methodological overlap. Two studies describing RNA-seq experiments clustered together due to shared terminology around differential expression, up-and-down-regulation, and enrichment analysis, even when the biological systems differed. These connections arise from shared vocabulary, not deeper conceptual links. The researchers call these false positives "paracites," in analogy with LLM hallucinations: surface similarity masquerading as conceptual connection.

Explicitly cited pairs corresponded to closely related findings from the same research group or line of work. OpenEval recovered relationships already present in the citation graph.

Implicitly cited pairs revealed subtle connections. Two papers might cite each other, but not for the specific result identified by OpenEval. The connection was recovered only through result-level comparison.

Uncited pairs revealed links between related studies with no direct citation. In one case, two papers independently examined timing-dependent long-term depression (tLTD) in different brain circuits. One showed that tLTD exists either with or without NMDA receptors, depending on synaptic connection. The other showed that NMDA receptors are required and mediate tLTD through non-ionotropic signaling.26 The studies did not cite each other because they worked on different circuits, but their results are directly relevant.

This is what a machine-readable scientific record enables: connections that no human would make because no human reads both papers.

What Does It Mean for a Machine to "Understand"?

Here is where the philosophy gets interesting.

The OpenEval system achieves 81% agreement with human peer review. It identifies uncited connections between papers. It costs under a dollar per manuscript. But does it "understand" the science?

The answer depends on what you mean by "understand." The system parses text and produces structured outputs that align with human judgments. It does not understand in the way a scientist understands. It cannot design experiments. It cannot intuit which claims are important. It cannot feel the difference between an interesting result and a boring one.

The researchers are careful about this: "In our framework, LLMs function as tools for parsing and organizing scientific content, not as arbiters of truth. Human judgment remains central at every stage: in designing experiments, interpreting results, evaluating claims, and formulating narratives that transmit ideas."27

And more pointedly: "This comparison is not an argument for replacing human reviewers. Rather, it serves as a concrete demonstration of how machine-readable representations make previously inaccessible analyses accessible."28

This is the right framing. The machine is an index, not an oracle. It makes previously impossible analyses possible. It does not replace human judgment; it creates structured representations on which human judgment can operate more efficiently.

The Epistemological Paradox

There is a deeper tension here that the paper does not resolve and perhaps cannot resolve.

Peer review was institutionalized in the 20th century, though its roots trace back to 1752.29 Its purpose was verification by qualified equals. Machine review inverts this. The machine is not a peer. It is not qualified in the sense that human experts are qualified. It has no domain expertise earned through years of training and practice. It pattern-matches against text.

And yet it agrees with human peers 81% of the time.

What does this tell us about human peer review? Perhaps that much of peer review is pattern-matching against text. Perhaps that 81% of scientific claims are straightforward enough that text analysis alone can verify them. Perhaps that the remaining 19% is where human expertise actually matters.

Or perhaps the agreement reflects the papers themselves. Published papers in a curated journal like eLife have already been filtered. The hard cases have been rejected. The surviving papers are the ones where machine and human evaluation converge because the evidence is clear.

The truly interesting test would be running OpenEval on preprints before peer review. What fraction would it flag as uncertain or unsupported? Would those flags correlate with eventual rejection? Would the machine catch errors that humans miss, or miss errors that humans catch?

The infrastructure is in place. OpenAlex indexes about 209 million works, with about 50,000 added daily.30 The experiment could be run.

What Comes Next

Machine-readable science is not a technical problem. The tools exist. RDF exists. Knowledge graphs exist. LLMs can extract structured claims from unstructured text. The cost is under a dollar per paper.

Machine-readable science is a social problem. It requires scientists to produce structured outputs at publication time. It requires journals to adopt formats like JATS. It requires funders to incentivize open data and reproducibility. It requires communities to agree on domain-specific vocabularies.

The researchers offer three recommendations:31

-

Develop shared nomenclature standards. The semantic web failed partly because ontology agreement is hard. But domains can develop local standards that enable machine readability within a field even without universal agreement.

-

Build novel open-publication, reproducible, and transparent infrastructure. eLife's Publish, Review, Curate model shows what is possible: manuscripts, peer reviews, and author responses all published in machine-readable JATS format.32

-

Train models on structured scientific outputs. As machine-readable scientific data accumulates, it becomes training data for better models.

The machine learning community is well-positioned to lead this change, as it has the cultural influence to normalize machine-readable dissemination of scientific results, beginning in well-defined domains with existing standards and evaluation mechanisms.33

The mathlib project provides a concrete example. Work in the mathematics community has shown how formal structure, through the Lean proof assistant, enables verification, reuse, and cumulative progress. Lean complements mathematical publications; it does not replace them.34

Figure 8: The relationship between manuscript length and number of claims extracted. Typical papers yield 100-200 machine-extracted claims, with longer documents producing proportionally more. Source: Booeshaghi et al.

Figure 8: The relationship between manuscript length and number of claims extracted. Typical papers yield 100-200 machine-extracted claims, with longer documents producing proportionally more. Source: Booeshaghi et al.

The Limits and the Promise

The researchers are honest about what their work cannot do.

Retrofitting machine readability onto existing papers using LLMs is costly, resource-intensive, and imperfect. Grouping claims into results required an additional inferential step by the model, which may not align with how the authors or reviewers understood the work.35

The clear implication: machine-readable science should be generated at the point of publication, not after the fact.36 Science should be disseminated in structured and machine-readable form, along with traditional human-readable narratives.

This is not a call to replace narratives. "Human-readable narratives remain essential. They support interpretation, creativity, and the communication of ideas."37 But narratives need not be the sole representation of scientific output. A paper can be both a story for humans and a structured dataset for machines.

The semantic web failed because it tried to make all knowledge formally representable from the top down. Science is different. Scientific claims have relatively narrow scope. They make specific assertions about specific evidence. They can be extracted, grouped, evaluated, and compared in ways that general knowledge cannot.

Perhaps machine-readable science will succeed where the semantic web failed, not because the technology is better, but because the domain is more tractable.

The machines are learning to read. The question is whether we will give them something worth reading.

References

Footnotes

-

Booeshaghi, A. S., Luebbert, L., & Pachter, L. (2026). Science should be machine-readable. bioRxiv. "Preprint servers like arXiv, bioRxiv, and medRxiv host hundreds of thousands of papers (arXiv: 2,935,336; bioRxiv and medRxiv: >389,000, as of January 16, 2026)." ↩ ↩2

-

Booeshaghi et al. (2026). "Howard Percy Robertson's review of Albert Einstein's 1936 paper rejecting gravitational waves identified errors in the non-existence proof. Robertson showed that recasting the metric in cylindrical coordinates removed the singularities." ↩

-

Based on arXiv submission rates and preprint server growth. See OpenAlex documentation. ↩

-

Booeshaghi, A. S., Luebbert, L., & Pachter, L. (2026). Science should be machine-readable. bioRxiv. https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.64898/2026.01.30.702911v1 ↩ ↩2

-

W3C. (2014). RDF 1.1 Concepts and Abstract Syntax. "RDF graphs are sets of subject-predicate-object triples, where the elements may be IRIs, blank nodes, or datatyped literals." ↩

-

Hogan, A. et al. (2021). Knowledge Graphs. ACM Computing Surveys. "The modern incarnation of the phrase stems from the 2012 announcement of the Google Knowledge Graph." ↩

-

Hogan et al. (2021). "Knowledge graphs have been announced by Airbnb, Amazon, eBay, Facebook, IBM, LinkedIn, Microsoft, Uber, and more besides." ↩

-

Wikidata Introduction. "Wikidata is a free, collaborative, multilingual, secondary knowledge base... The data in Wikidata is published under the Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication 1.0." ↩

-

Analysis based on semantic web adoption patterns. Simpler graph structures like property graphs gained more traction because they traded formal rigor for practical usability. ↩

-

Booeshaghi et al. (2026). "LLMs are general-purpose parsers of natural language. Any scientific artifact that can be represented as text, papers, code, methods, and reviews, can be ingested, transformed, and reorganized by an LLM." ↩

-

Booeshaghi et al. (2026). "OpenEval implements a structured, five-stage review: (1) extraction of atomic, factual, explicit and implicit claims from a manuscript, (2) grouping of those claims into research results, (3) evaluation of those research results by an LLM, (4) evaluation of the research results made by peer review commentary, and (5) comparison of the OpenEval and peer evaluations." ↩

-

Booeshaghi et al. (2026). "OpenEval extracted 1,964,602 claims in total from the eLife corpus (16,087 manuscripts)" and "Using cllm, OpenEval extracted an average of ~112 claims per paper." ↩

-

Booeshaghi et al. (2026). "Claims consisted of literal excerpts from the original manuscripts that are mapped back to the text itself." ↩

-

Booeshaghi et al. (2026). "Across manuscripts, the most prominent evidence type was data, which accounted for approximately ~75% of all evidence types, followed by citations (~20%) and explicit knowledge claims (~10%)." ↩ ↩2

-

Booeshaghi et al. (2026). "Explicit claims were overwhelmingly supported by data and citations, whereas implicit claims showed a shift toward inference and speculation." ↩

-

Booeshaghi et al. (2026). "OpenEval and human reviewers agreed on most research results. Of the 41,232 results evaluated by both, 33,247 (81%) received matching assessments... Outright disagreement was rare, occurring in only 304 cases (0.7%)." ↩

-

Booeshaghi et al. (2026). "The low unsupported rate (0.09%) is expected for published work that has been peer-reviewed." ↩

-

Booeshaghi et al. (2026). "OpenEval assessed 92.8% of research claims in a manuscript on average, while human reviewers were more selective, assessing only 68.1% of claims on average." ↩

-

Booeshaghi et al. (2026). "OpenEval found results that peer reviewers did not address (866 major and 8,373 minor), some of which were evaluated as 'Uncertain' or 'Unsupported' by OpenEval." ↩

-

Booeshaghi et al. (2026). "Evaluation and agreement patterns remained stable over time. The proportion of matching assessments did not change meaningfully across publication dates." ↩

-

Booeshaghi et al. (2026). "Open-access journals like Cell, Nature, and Science publish peer-reviewed papers, but charge author fees (for example, up to $12,690 per paper at Nature)." ↩

-

Booeshaghi et al. (2026). "Extracting claims from the entire eLife corpus cost a total of $6,844.77 ($0.43 per manuscript). Evaluation with OpenEval cost $5,287.94 ($0.33 per manuscript)." ↩

-

Booeshaghi et al. (2026). "Total single-thread processing time of 1,252.9h (280.38s per manuscript) for claim extraction and 422.7h (94.58s per manuscript) for evaluation." ↩

-

Booeshaghi et al. (2026). "We generated vector embeddings for all extracted claims and all OpenEval results using a fixed text embedding model (OpenAI text-embedding-3-large)." ↩

-

Booeshaghi et al. (2026). Analysis of result-level connections across manuscripts, Table S1. ↩

-

Booeshaghi et al. (2026). "Uncited pairs can reveal links between related studies with no direct citation link." ↩

-

Booeshaghi et al. (2026). "In our framework, LLMs function as tools for parsing and organizing scientific content, not as arbiters of truth. Human judgment remains central at every stage: in designing experiments, interpreting results, evaluating claims, and formulating narratives that transmit ideas." ↩

-

Booeshaghi et al. (2026). "This comparison is not an argument for replacing human reviewers. Rather, it serves as a concrete demonstration of how machine-readable representations make previously inaccessible analyses accessible." ↩

-

Booeshaghi et al. (2026). "Peer review is a relatively recent innovation in the scientific enterprise. First established in 1752, peer review became a systematic, institutionalized process only in the 20th century." ↩

-

Priem, J. et al. (2022). OpenAlex: A fully-open index of scholarly works. "OpenAlex indexes about 209M works, with about 50,000 added daily." ↩

-

Booeshaghi et al. (2026). "Call to action: (1) Develop shared nomenclature standards. (2) Build novel open-publication, reproducible, and transparent infrastructure. (3) Train models on structured scientific outputs." ↩

-

Booeshaghi et al. (2026). "The eLife journal, which was founded in 2012, adopted the permissive CC BY license from the start and gave authors the option to publish peer reviews along with their papers." ↩

-

Booeshaghi et al. (2026). "The machine learning community is well-positioned to lead this change, as it has the cultural influence to normalize machine-readable dissemination of scientific results, beginning in well-defined domains with existing standards and evaluation mechanisms." ↩

-

Booeshaghi et al. (2026). "The mathlib project is a concrete example of this approach. Work in the mathematics community has shown how formal structure, through the Lean proof assistant, enables verification, reuse, and cumulative progress." ↩

-

Booeshaghi et al. (2026). "Retrofitting machine readability onto existing papers using LLMs is costly, resource-intensive, and imperfect. More importantly, grouping claims into results required an additional inferential step by the model, which may not align with how the authors or reviewers understood the work." ↩

-

Booeshaghi et al. (2026). "Machine-readable science should be generated at the point of publication, not after the fact." ↩

-

Booeshaghi et al. (2026). "Human-readable narratives remain essential. They support interpretation, creativity, and the communication of ideas." ↩