From Diffusion to Clinic: How AI Is Designing Antibodies from Scratch

In March 2024, researchers at the Baker Lab published the first successful demonstration of de novo antibody design from computation alone. Their RFdiffusion-based approach generated VHH antibodies targeting influenza hemagglutinin with binding affinities of 78 nM, and cryo-electron microscopy confirmed the designed structures matched computational predictions with a backbone RMSD of just 1.45 angstroms. The CDR3 loop, typically the most challenging region to predict, showed even better agreement at 0.8 angstroms. This was not optimization of existing antibodies or screening of random libraries. It was antibodies designed from nothing but a target epitope and an algorithm.

For an industry where "antibodies are the dominant class of protein therapeutics, with over 160 antibody therapeutics currently licensed globally and a market value expected to reach US$445 billion in the next 5 years," the implications are substantial. Several AI-native biotech companies have reported accelerated timelines from computational design to clinical candidates, though questions remain about the relative contribution of AI versus traditional optimization methods in these programs.

But what exactly changed? How did we go from antibody discovery requiring millions of experimental variants to computational design achieving atomic-level accuracy? And perhaps more importantly, what are the actual limitations practitioners should understand before integrating these approaches into their pipelines?

The Antibody Design Problem

Antibodies recognize antigens through their complementarity-determining regions, six hypervariable loops that form the binding interface: "CDR-H1, CDR-H2, and CDR-H3 on the heavy chain and CDR-L1, CDR-L2, and CDR-L3 on the light chain." Of these, "CDR-H3 is the most structurally diverse domain of the antibody and often determines antigen recognition." This diversity creates the core challenge.

"A CDR of length L can theoretically have up to 20^L different amino acid sequences owing to the 20 types of amino acids that can be placed at each position." For a typical CDR-H3 of 12 residues, that translates to roughly 4 x 10^15 possible sequences. "Traditional approaches to antibody design predominantly rely on animal immunization and computational methods" that search this space through biological selection rather than rational design. Phage display libraries explore perhaps 10^6 to 10^10 variants. Hybridoma technology relies on the immune system's own evolutionary search. Both approaches work, but they are screening methods at their core: you generate diversity, then select for function.

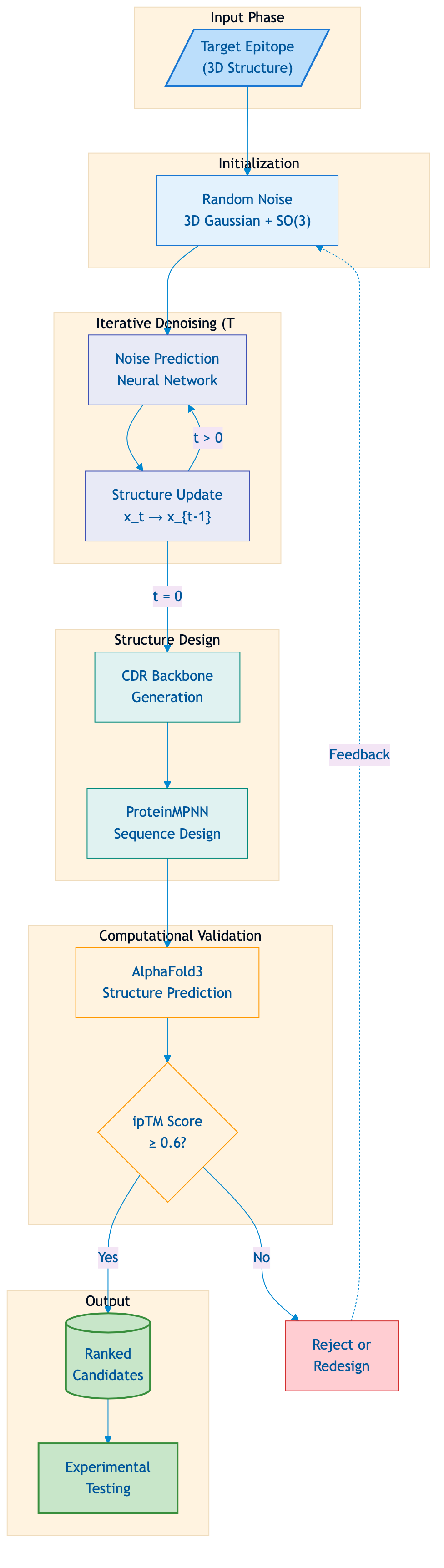

Figure 1: RFdiffusion Antibody Design Pipeline. The computational workflow for de novo antibody design begins with a target epitope structure and generates candidate antibodies through iterative denoising. AlphaFold3 validates designs using ipTM scores, with designs below threshold either rejected or sent back for redesign. Source: Diagram based on Watson et al. 2024.

Figure 1: RFdiffusion Antibody Design Pipeline. The computational workflow for de novo antibody design begins with a target epitope structure and generates candidate antibodies through iterative denoising. AlphaFold3 validates designs using ipTM scores, with designs below threshold either rejected or sent back for redesign. Source: Diagram based on Watson et al. 2024.

The limitation is not just time. These methods provide limited predictive power. You screen, you find binders, but you do not necessarily understand why they bind or how to systematically improve them.

Diffusion Models: The Core Technical Innovation

The breakthrough enabling de novo antibody design came from an unexpected direction: image generation. "Denoising diffusion probabilistic models (DDPMs) have emerged as a powerful technique for learning and sampling from complex high-dimensional protein distributions."

The core idea is elegantly simple. Start with a known protein structure, progressively add noise until it becomes random, then train a neural network to reverse this process. At generation time, begin with pure noise and iteratively denoise to produce a novel structure. "RFdiffusion is trained such that at time T a sample is drawn from the prior distribution (3D Gaussian for translations and uniform SO3 for rotations)." This mathematical framework ensures generated structures are physically plausible regardless of their orientation in space.

For antibody design, the model is conditioned on a target epitope. You specify where you want the antibody to bind, and diffusion generates backbone conformations that should complement that surface. ProteinMPNN then designs amino acid sequences predicted to fold into these conformations. AlphaFold3 validates that the designed sequences actually adopt the intended structures.

The validation was thorough. The Baker Lab team designed thousands of VHH candidates against multiple targets. "Cryo-electron microscopy confirms the binding pose of designed VHHs targeting influenza haemagglutinin and Clostridium difficile toxin B (TcdB)." The structural accuracy was remarkable: "The structure of influenza haemagglutinin bound to two copies of VHH_flu_01 reveals a VHH backbone that is very close to the RFdiffusion design, with a calculated root mean square deviation (RMSD) of 1.45 A."

For context, an RMSD below 2 angstroms generally indicates atomic-level accuracy in structural biology. The designed antibodies were not just folding correctly; they were adopting almost exactly the conformations predicted computationally.

Binding Affinity: Good Enough for a Starting Point

Structure is necessary but not sufficient. Antibodies must actually bind their targets with therapeutically relevant affinity. Here, the picture is more nuanced.

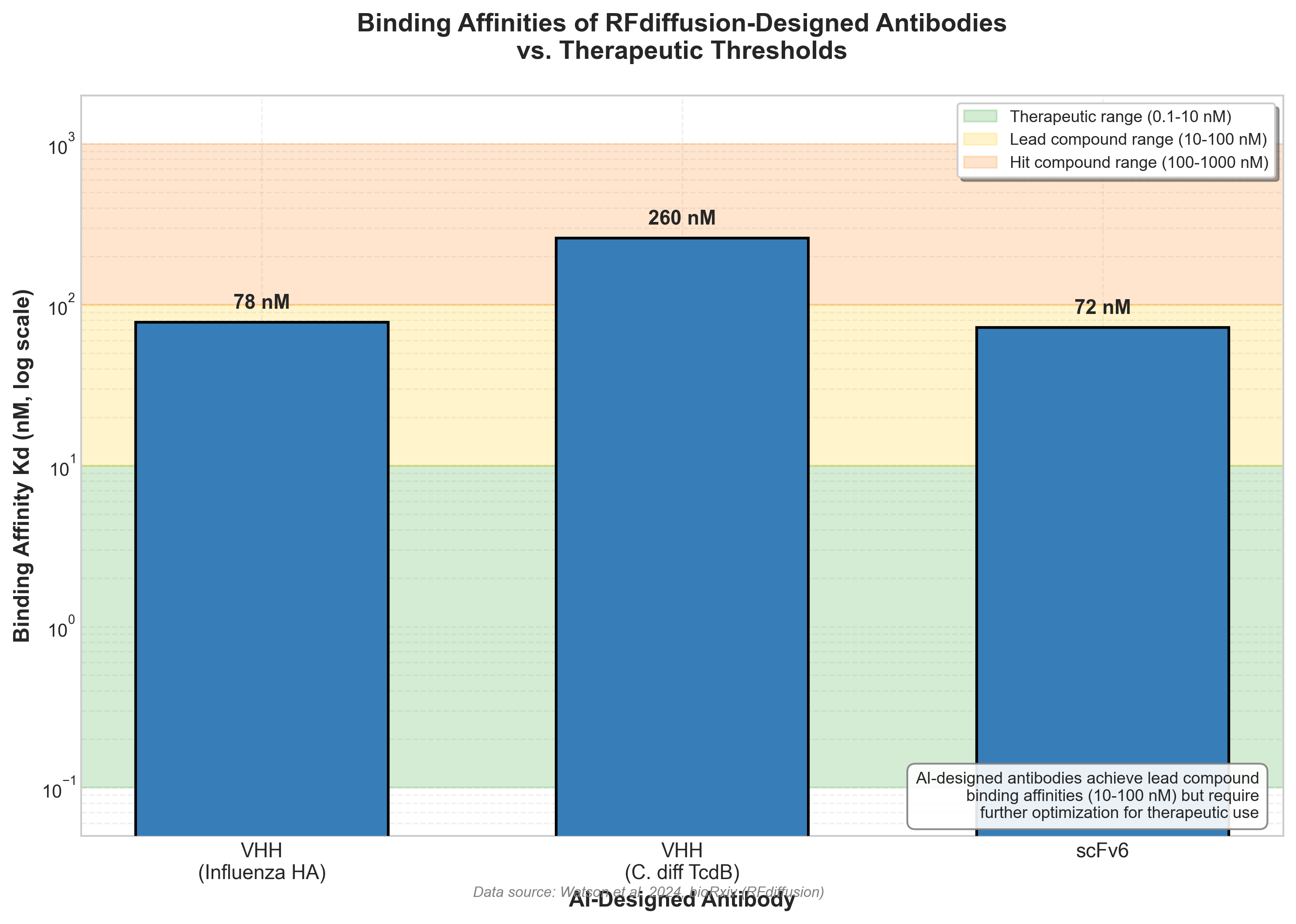

"Initial computational designs exhibit modest affinity (tens to hundreds of nanomolar Kd)." The highest affinity VHH to influenza hemagglutinin achieved a dissociation constant of 78 nM. "For TcdB the best-designed VHH had Kd = 260 nM." For scFv designs, "the highest affinity binder scFv6 had a Kd of 72 nM."

Figure 2: Binding affinities of RFdiffusion-designed antibodies compared to therapeutic thresholds. AI designs achieve lead compound range (10-100 nM) but require optimization for therapeutic use. Source: Watson et al. 2024, bioRxiv.

Figure 2: Binding affinities of RFdiffusion-designed antibodies compared to therapeutic thresholds. AI designs achieve lead compound range (10-100 nM) but require optimization for therapeutic use. Source: Watson et al. 2024, bioRxiv.

For comparison, approved therapeutic antibodies typically have single-digit nanomolar or sub-nanomolar affinities. The AI-designed antibodies are functional binders, but they are starting points rather than finished therapeutics.

This is where affinity maturation becomes critical. "OrthoRep has been shown to drive the rapid affinity maturation of yeast surface-displayed antibodies" and "affinity-matured VHHs improved binding affinities by approximately two orders of magnitude." Starting from 78 nM and improving 100-fold puts you solidly in therapeutic range while maintaining epitope selectivity.

The combination matters: computational design provides starting points that are structurally accurate and epitope-specific, then directed evolution or computational optimization refines affinity. Neither approach alone would be as efficient.

AlphaFold3: The Validation Filter

A critical question for any generative model: how do you know which designs will actually work before expensive experimental testing? AlphaFold3 provides part of the answer.

"AlphaFold 3 demonstrates substantially improved accuracy over many previous specialized tools: far greater accuracy for protein-ligand interactions compared with state-of-the-art docking tools." More specifically for antibodies, "the new AlphaFold model demonstrates substantially higher antibody-antigen prediction accuracy compared with AlphaFold-Multimer v.2.3." The statistical evidence is clear: "AF3 greatly outperforms classical docking tools such as Vina (Fisher exact test P = 2.27 x 10^-13)."

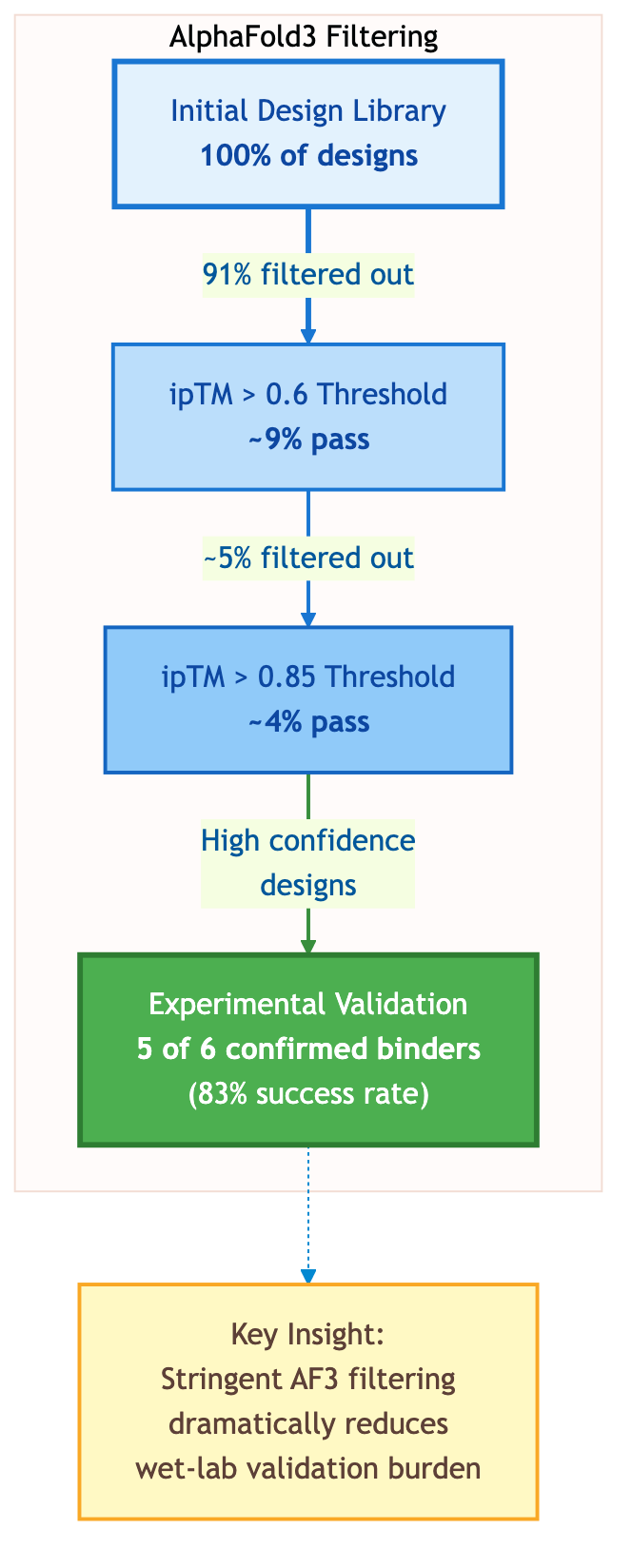

What makes this practically useful is the correlation between AlphaFold3's confidence scores and experimental success. "AlphaFold3 interface predicted template modelling (ipTM) score is predictive of binding success (area under the curve = 0.86)." An AUC of 0.86 means the score correctly ranks binders above non-binders 86% of the time.

Figure 3: AlphaFold3 Filtering Dramatically Reduces Experimental Burden. Computational filtering using ipTM scores eliminates over 90% of designs before wet-lab validation. Among high-confidence designs (ipTM > 0.85), experimental testing confirms binding for 5 out of 6 candidates (83% success rate). Source: Watson et al. 2024.

Figure 3: AlphaFold3 Filtering Dramatically Reduces Experimental Burden. Computational filtering using ipTM scores eliminates over 90% of designs before wet-lab validation. Among high-confidence designs (ipTM > 0.85), experimental testing confirms binding for 5 out of 6 candidates (83% success rate). Source: Watson et al. 2024.

The filtering is aggressive: "only 9% of VHH designs have an ipTM > 0.6." Even more selective, "only 4% of the initial design library has ipTM > 0.85 whereas 5 out of 6 experimentally confirmed designs pass this threshold." For practitioners, this means AlphaFold3 can computationally eliminate the vast majority of non-functional designs before any wet-lab work.

Beyond RFdiffusion: Alternative Diffusion Approaches

RFdiffusion is not the only diffusion-based approach producing results. The field has developed multiple architectures, each with distinct strengths.

IgDiff uses SE(3)-equivariant diffusion specifically optimized for antibody variable domains. The key innovation is geometric equivariance: the model's predictions transform correctly under rotations and translations. "IgDiff produces highly designable antibodies that can contain novel binding regions with all 28 tested antibodies expressing with high yield." The model generates structurally plausible novelty: "IgDiff generated antibodies have mean CDR H3 RMSD to the closest match of 1.39A +/- 0.56 compared to 1.50A +/- 0.74 for naturally observed antibodies."

Direct comparisons reveal important capability differences: "IgDiff achieves 74% pass rate on combined test for CDR H3 length change task compared to 6% for RFDiffusion" and "IgDiff achieves 93% success for light chain design task with RFDiffusion producing no valid light chains."

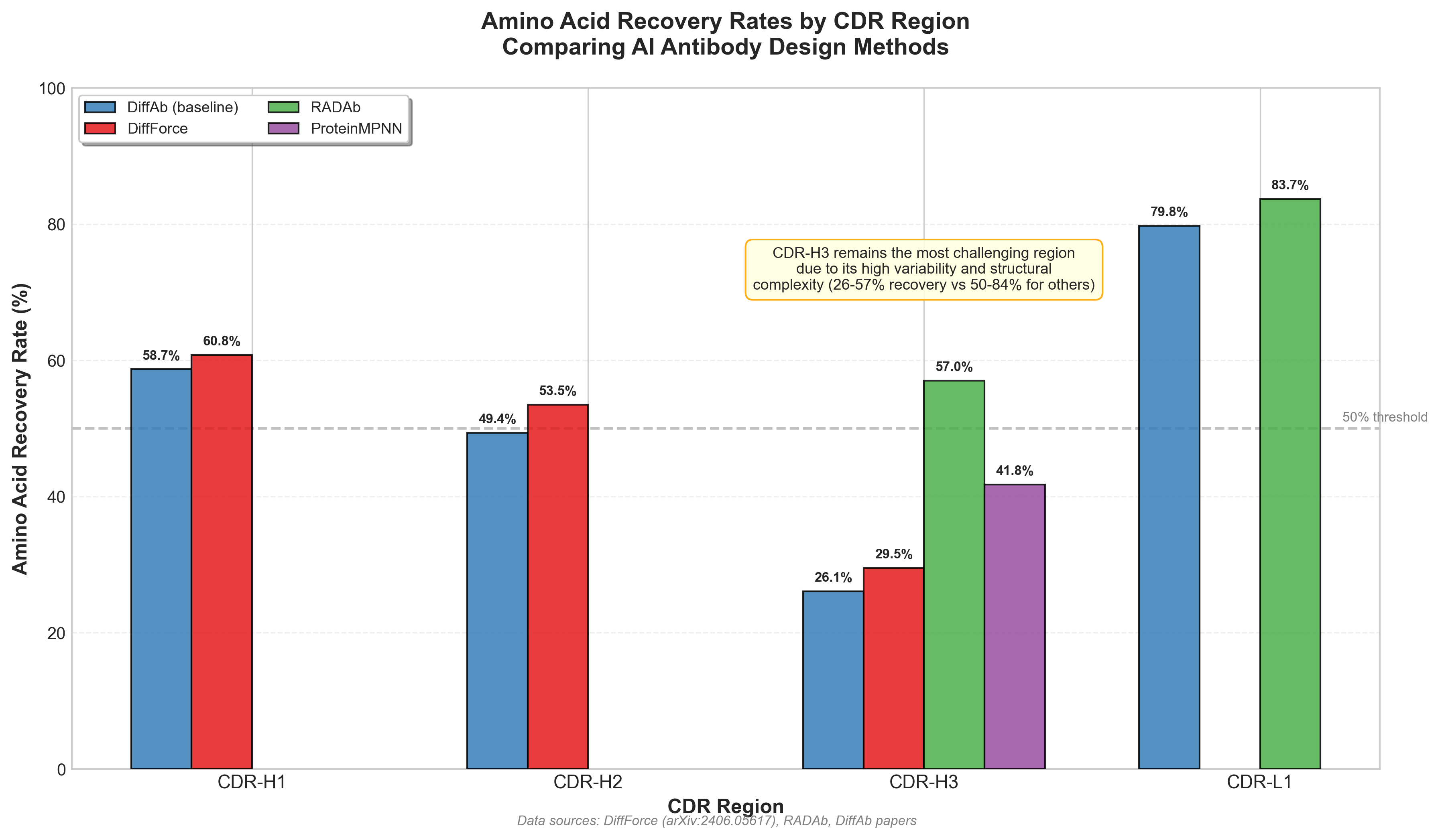

DiffForce integrates physics-based feedback into the diffusion process. "Physics-based force fields which approximate atomic interactions provide a coarse but universal source of information to better align antibody designs with target interfaces." The model "employs forces to guide the diffusion sampling process," achieving consistent improvements over baseline diffusion: "DIFFFORCE outperforms DIFFAB with AAR 60.78% vs 58.70% for H1, 53.51% vs 49.37% for H2, and 29.52% vs 26.08% for H3."

RADAb takes a retrieval-augmented approach. "RADAb leverages a set of structural homologous motifs that align with query structural constraints to guide the generative model in inversely optimizing antibodies." By grounding generation in known structural patterns, it achieves strong performance on challenging cases: "RADAb achieves state-of-the-art performance with an 8.08% AAR gain in long CDR H3 inverse folding task." For the hardest sequences: "for long CDR-H3 sequences (length > 14) RADAb achieves AAR of 51.35% compared to 42.26% for Diffab-fix."

AbMEGD combines multi-scale representations with E(3)-equivariant graph diffusion. "AbMEGD integrates Multi-scale Equivariant Graph Diffusion for antibody sequence and structure co-design" by combining "atomic-level geometric features with residue-level embeddings capturing local atomic details and global sequence-structure interactions." Performance gains are substantial: "AbMEGD achieves a 10.13% increase in amino acid recovery, a 3.32% rise in improvement percentage, and a 0.062 A reduction in root mean square deviation within the critical CDR-H3 region compared to DiffAb."

Figure 4: Amino acid recovery rates by CDR region for different AI antibody design methods. CDR-H3 remains the most challenging region due to its high variability, with recovery rates of 26-57% compared to 50-84% for other CDRs. Sources: DiffForce (arXiv:2406.05617), RADAb papers.

Figure 4: Amino acid recovery rates by CDR region for different AI antibody design methods. CDR-H3 remains the most challenging region due to its high variability, with recovery rates of 26-57% compared to 50-84% for other CDRs. Sources: DiffForce (arXiv:2406.05617), RADAb papers.

Graph Neural Networks for Affinity Optimization

While diffusion models excel at structure generation, graph neural networks have emerged as the leading approach for predicting and optimizing binding affinity from existing structures.

GearBind uses geometric message passing on protein graphs to predict binding affinity changes from mutations. The model was pretrained on "non-redundant subset of CATH v4.3.0 domains which contains 30948 experimental protein structures with less than 40% sequence identity." On the SKEMPI benchmark containing "7085 ddG measurements on 348 protein complexes," GearBind achieves "MAE 1.115 RMSE 1.611 PearsonR 0.676 SpearmanR 0.525."

The experimental validation is concrete: "ELISA EC50 values of the designed antibody mutants are decreased by up to 17 fold and KD values by up to 6.1 fold." For a specific application targeting SARS-CoV-2: "CR3022 against SARS-CoV-2: 7 out of 10 single-point mutants and 9 out of 10 multi-point mutants showed increased binding."

AntiBMPNN demonstrates the value of antibody-specific training, achieving "perplexity of 1.5 and over 80% sequence recovery" with "75% success rate in single-point antibody design." Direct comparisons show substantial improvements over general protein models: for the CDR1 of huJ3 (an anti-HIV nanobody), AntiBMPNN achieved "EC50 of 9.2 nM better than ProteinMPNN (135.2 nM) and AntiFold (59.3 nM)."

Language Models: Learning from Billions of Sequences

Parallel to structure-based approaches, antibody language models trained on massive sequence databases provide complementary capabilities. IgBert and IgT5 were "trained on more than two billion unpaired sequences and two million paired sequences of light and heavy chains present in the Observed Antibody Space dataset."

The architectural scale is significant: "IgBert has 30 layers, 1024 hidden size, 16 attention heads and 420M parameters while IgT5 has 24 layers, 1024 hidden size, 32 attention heads and 3B parameters." Training required "32 A100 GPUs using a distributed DeepSpeed ZeRO Stage 2 strategy."

These models capture evolutionary information about antibody sequences, enabling tasks like humanization assessment, developability prediction, and sequence optimization within evolutionary constraints. For sequence recovery, "IgT5 achieves CDR-H3 sequence recovery of 0.6196 and Total VH recovery of 0.9163." The combination of language model understanding of sequence space with diffusion model generation of structural space represents the current state-of-the-art for integrated design.

Biologically-Inspired Multi-Expert Approaches

Recent work draws direct inspiration from how the immune system actually optimizes antibodies. A framework mimicking B cell affinity maturation "employs multiple specialized experts (van der Waals, molecular recognition, energy balance and interface geometry) whose parameters evolve during generation based on iterative feedback."

This approach achieves "7% reduction in CDR-H3 RMSD, 9% increase in hotspot coverage, 12% better interface pAE and 5% higher shape complementarity" compared to baselines. Success rates tell the story: "our method achieves success rate of 41.1% +/- 10.5 compared to RFAntibody 36.7% +/- 14.0 and DiffAb 11.1% +/- 17.0."

The success criteria used in these evaluations deserve attention: "Successful antibody designs must satisfy: CDR-H3 RMSD < 3.0 A, mean pAE < 10.0, and mean interaction pAE (ipAE) < 10.0." DiffAb's baseline performance of "only 11.1% +/- 17.0 success rate" indicates how challenging sequence-structure co-design remains even with sophisticated generative models.

What Still Does Not Work

The progress is real, but so are the limitations. Several critical challenges remain unresolved, and practitioners should understand them before committing resources.

Modest initial affinities require optimization. The best de novo designs achieve tens of nanomolar Kd, not the single-digit nanomolar or sub-nanomolar affinities of marketed therapeutics. The affinity maturation step is not optional for therapeutic applications.

In silico predictions frequently fail in vitro. As one paper notes directly, "many antibodies sampled in silico from diffusion models fail to demonstrate functionality when tested in vitro." Computational binding does not guarantee experimental binding. The gap between prediction and reality remains substantial.

Training data constrains model performance. The SAbDab database, the primary source of antibody-antigen structures, "comprises fewer than ten thousand antigen-antibody complex structures." This is orders of magnitude smaller than the datasets available for general protein structure prediction. More data would enable better models.

Developability prediction lags binding prediction. Binding affinity is only one property of a therapeutic antibody. Immunogenicity, aggregation propensity, expression levels in mammalian systems, and pharmacokinetics all matter for clinical success. Current AI approaches focus primarily on binding, with developability assessment still requiring experimental validation.

CDR-H3 remains the hardest region. Despite progress, the most variable loop remains the most challenging. E(3)-equivariant methods help, and "E(3)-equivariant diffusion method ensures geometric precision, computational efficiency, and robust generalizability for complex antigens," but CDR-H3 accuracy still trails other regions.

Clinical Translation: Where Are We Actually?

Despite the limitations, AI-designed antibodies are reaching the clinic. Two VHH-based therapies have already been approved by the FDA, "with many clinical trials ongoing." The broader context matters: this regulatory pathway is now established.

Several AI-native biotech companies have reported accelerated development timelines for computationally designed candidates. However, honest assessment requires acknowledging uncertainty. The relationship between computational design and traditional optimization in these programs is not always transparent. STAT News and other outlets have raised questions about the extent to which clinical candidates are truly "AI-designed" versus optimized using traditional methods with AI assistance at specific stages. The distinction matters for understanding what capabilities these tools actually provide in practice.

What is unambiguous is that computational methods are accelerating some portion of the discovery process. Whether that acceleration comes from pure de novo design or from more efficient optimization of existing scaffolds varies by program.

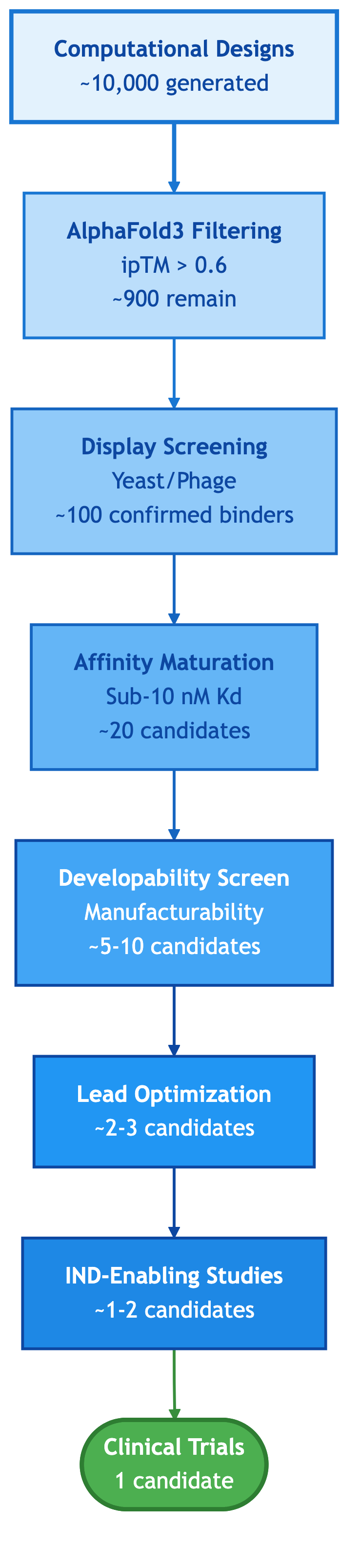

Figure 5: AI Antibody Development Pipeline Attrition. From computational designs through successive filtering stages (computational validation, display screening, affinity maturation, developability assessment), typical attrition yields 1-2 candidates suitable for clinical development. Attrition rates are illustrative of general industry patterns.

Figure 5: AI Antibody Development Pipeline Attrition. From computational designs through successive filtering stages (computational validation, display screening, affinity maturation, developability assessment), typical attrition yields 1-2 candidates suitable for clinical development. Attrition rates are illustrative of general industry patterns.

What This Means for Discovery Teams

For practitioners evaluating these approaches, several practical considerations emerge from the current evidence.

Computational design works as a starting point generator. RFdiffusion and related approaches produce VHHs and scFvs that fold correctly and bind intended targets with atomic-level structural accuracy. Expect initial designs to require optimization. Plan for affinity maturation cycles whether using directed evolution, yeast display, or additional computational optimization with tools like GearBind.

AlphaFold3 enables computational triage. The correlation between ipTM scores and binding success allows elimination of non-functional designs before wet-lab work. A stringent threshold (ipTM > 0.85) dramatically enriches for functional designs, with 5 out of 6 experimentally confirmed binders passing this bar.

Different tools serve different purposes. Diffusion models excel at generating novel CDR conformations. GNNs are better for predicting effects of specific mutations on existing antibodies. Language models provide evolutionary context and humanization guidance. Effective pipelines combine multiple approaches rather than relying on any single tool.

Validation infrastructure matters as much as algorithms. The companies advancing most quickly have integrated computational design with high-throughput experimental validation. Design alone is not sufficient. The speed comes from tight iteration between computation and experiment.

Antibody-specific training improves performance. Models trained on antibody-specific data (AntiBMPNN, IgDiff) outperform general protein models applied to antibodies. As structural databases grow, expect continued improvement, but current performance depends heavily on training data quality and relevance.

Looking Forward

The 2024 Nobel Prize in Chemistry, awarded to David Baker, John Jumper, and Demis Hassabis for computational protein design and structure prediction, signals the field's maturation. What was speculative five years ago is now producing clinical candidates.

Several developments will likely shape the near-term future. Integration of generative and predictive models will become standard, with pipelines combining RFdiffusion (or similar) for structure generation, language models for sequence optimization, and AlphaFold3 for validation representing the emerging best practice. Developability prediction will receive increased attention now that binding is addressable. Multi-objective optimization that simultaneously considers binding, stability, and manufacturability is the next frontier. Expanded target scope beyond classical viral and inflammatory targets will test whether these methods generalize to conformational epitopes, intracellular targets, and multi-specific designs.

The antibody field has shifted from searching sequence space to designing within it. The tools are imperfect, the timelines are compressed but not eliminated, and experimental validation remains essential. But the trajectory is clear: computational approaches are no longer auxiliary to antibody discovery. They are becoming central to it.

References

-

Watson et al. "Atomically accurate de novo design of single-domain antibodies." bioRxiv/Nature (2024).

-

AlphaFold3 paper. Nature (2024).

-

IgDiff paper. arXiv (2024).

-

DiffForce paper. arXiv (2024).

-

RADAb paper. arXiv (2024).

-

AbMEGD paper. arXiv (2025).

-

GearBind paper. Nature Communications (2024).

-

AntiBMPNN paper. (2024).

-

Large-scale paired antibody LM paper. PLOS Computational Biology (2024).

-

B-cell evolution diffusion paper. arXiv (2025).