Does RL Actually Make LLMs Smarter? A Critical Look at Reinforcement Learning for Reasoning

Six popular RLVR algorithms perform similarly and remain far from optimal in leveraging base model potential.1 That finding, from a paper accepted as a NeurIPS 2025 oral and ICML 2025 AI4MATH best paper, should give pause to anyone assuming reinforcement learning transforms how large language models reason.

Here's the uncomfortable pattern: RLVR-trained models dominate benchmarks at pass@1, yet base models consistently catch up as sampling increases. This suggests something counterintuitive: reinforcement learning may not be teaching LLMs to reason better. It might just be teaching them to find the right answer faster.

The distinction matters. If RLVR genuinely expands reasoning capacity, investing in RL training infrastructure is essential for building smarter models. If it merely optimizes search efficiency over existing capabilities, the calculus changes entirely. The evidence, drawn from recent NeurIPS and ICML research, points toward the latter interpretation.

This post examines what the empirical data actually shows, why the pass@k metric reveals something benchmarks obscure, and what this means for practitioners deciding where to invest their training compute.

The Conventional Wisdom: RL Makes Models Think Better

The narrative around RLVR (Reinforcement Learning with Verifiable Rewards) runs something like this: base models have latent reasoning abilities, and RL training activates or enhances them. DeepSeek-R1's results seemed to confirm this story.

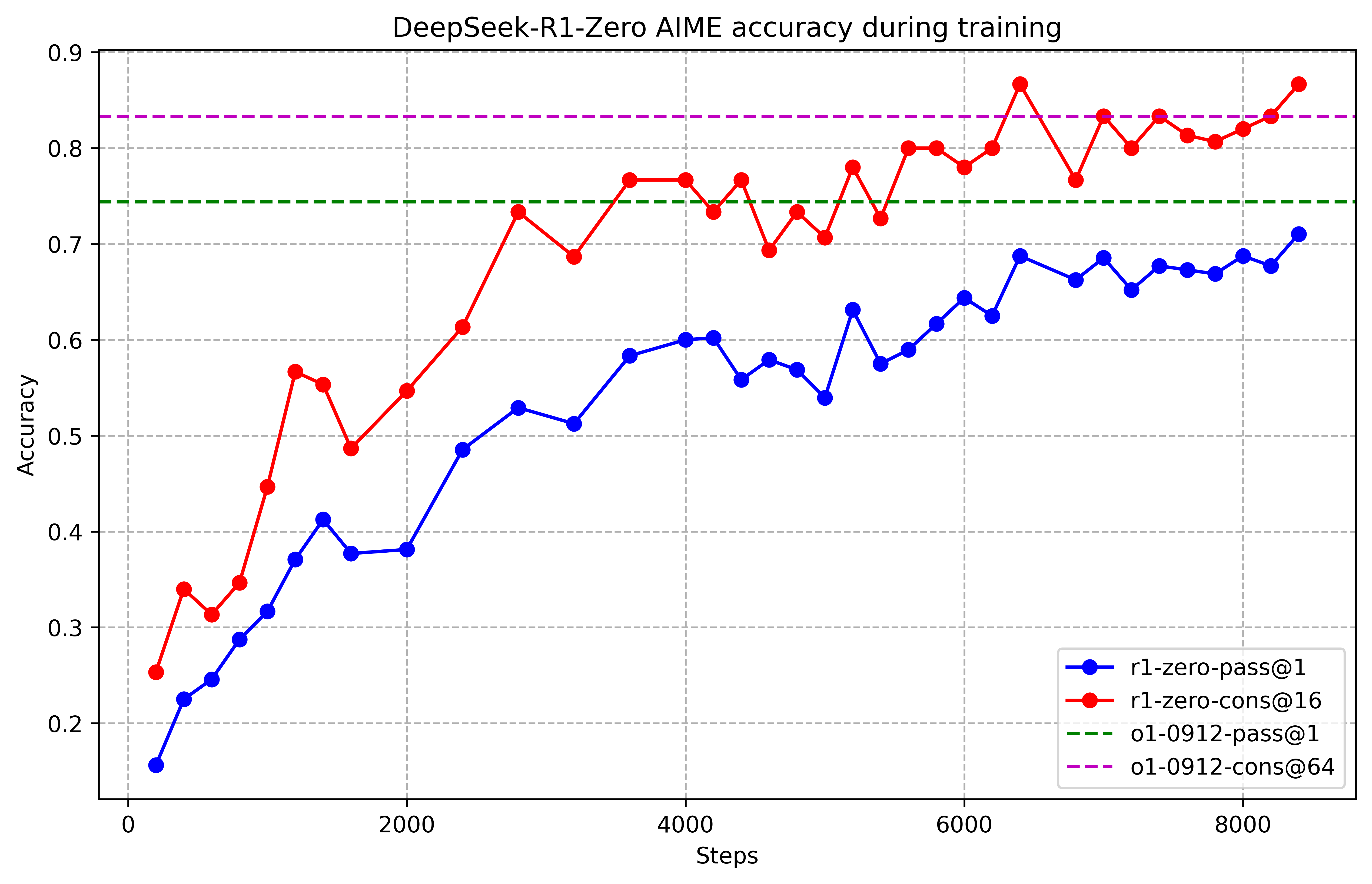

The model improved from roughly 15% to 71% accuracy on AIME problems through pure RL training. Performance continued climbing over thousands of training steps.2

Figure 1: DeepSeek-R1-Zero AIME accuracy progression showing pass@1 (blue) versus cons@16 (red) over 8000 training steps. Dashed lines indicate o1-0912 baselines. Notice the persistent gap between single-attempt and multi-attempt performance. Source: DeepSeek-R1

Figure 1: DeepSeek-R1-Zero AIME accuracy progression showing pass@1 (blue) versus cons@16 (red) over 8000 training steps. Dashed lines indicate o1-0912 baselines. Notice the persistent gap between single-attempt and multi-attempt performance. Source: DeepSeek-R1

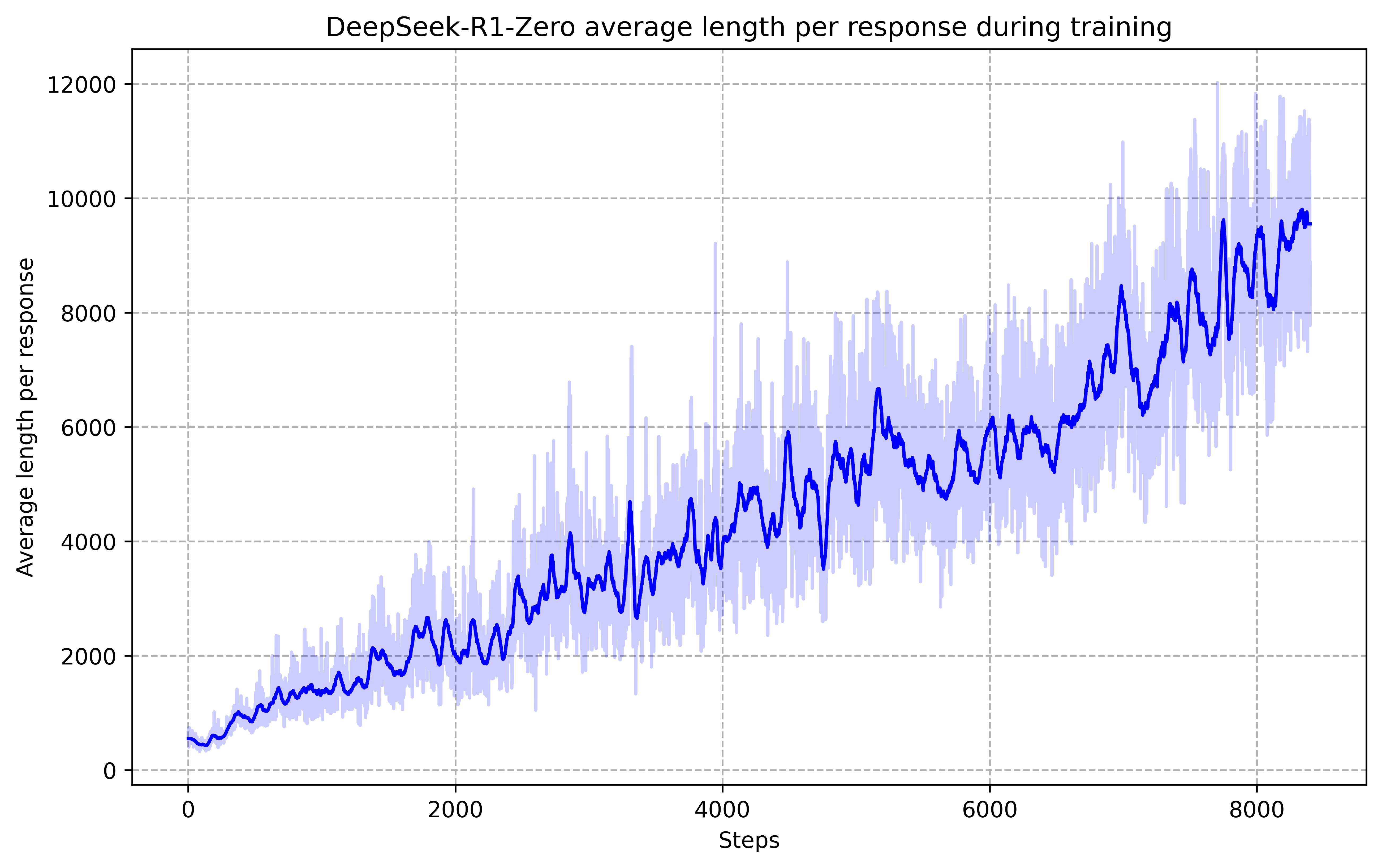

The training curve looks compelling. Performance rises steadily, surpassing OpenAI's o1 baseline. Response length increases dramatically as the model learns to generate longer reasoning chains. The inference costs are real, but so is the accuracy improvement.

Figure 2: Average response length increasing from approximately 500 tokens to 10,000 tokens during RL training. Source: DeepSeek-R1

Figure 2: Average response length increasing from approximately 500 tokens to 10,000 tokens during RL training. Source: DeepSeek-R1

This success story, combined with similar results from other frontier labs, established RLVR as the path to better reasoning. InstructGPT demonstrated that "outputs from the 1.3B parameter InstructGPT model are preferred to outputs from the 175B GPT-3, despite having 100x fewer parameters."3 The assumption became widespread: RL teaches models new ways to think.

But the assumption rests on a specific interpretation of the metrics.

What the Pass@K Evidence Actually Shows

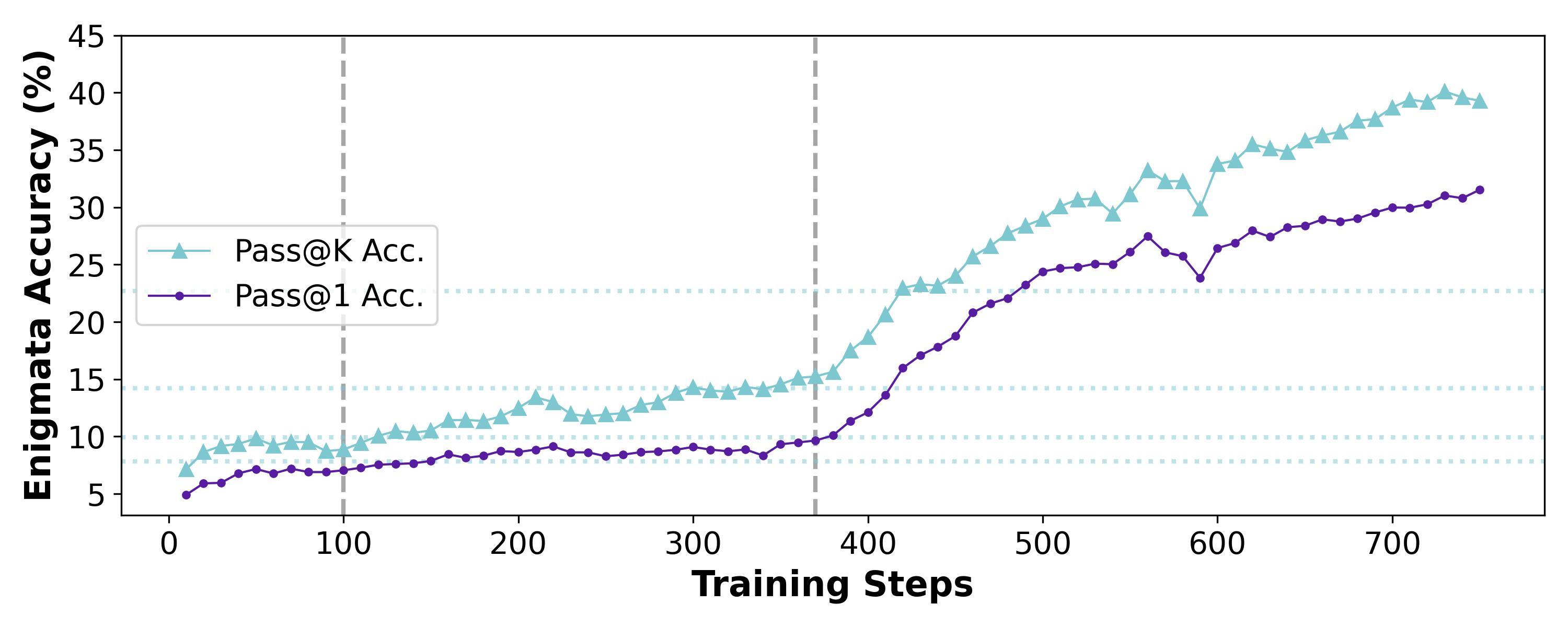

Here is the finding that challenges the narrative: "the phenomenon that some post-RLVR models improve the Pass@1 metric but fail to enhance the Pass@K metric compared to the base (pre-RLVR) model."4

Let that sink in. RLVR models beat base models when you give each model one attempt. But when you allow multiple attempts, base models catch up.

Figure 3: Enigmata accuracy comparing Pass@K (cyan triangles) versus Pass@1 (purple circles) over training steps. Pass@K reaches approximately 40% while Pass@1 reaches approximately 31%, demonstrating different optimization targets produce different capabilities. Source: Pass@k Training

Figure 3: Enigmata accuracy comparing Pass@K (cyan triangles) versus Pass@1 (purple circles) over training steps. Pass@K reaches approximately 40% while Pass@1 reaches approximately 31%, demonstrating different optimization targets produce different capabilities. Source: Pass@k Training

The implications are significant. If RL were genuinely expanding reasoning capacity, we would expect the improvement to persist regardless of how many samples we draw. Instead, the data suggests "all correct reasoning paths are already present in the base model, and RLVR merely improves sampling efficiency at the cost of reducing overall reasoning capacity."5

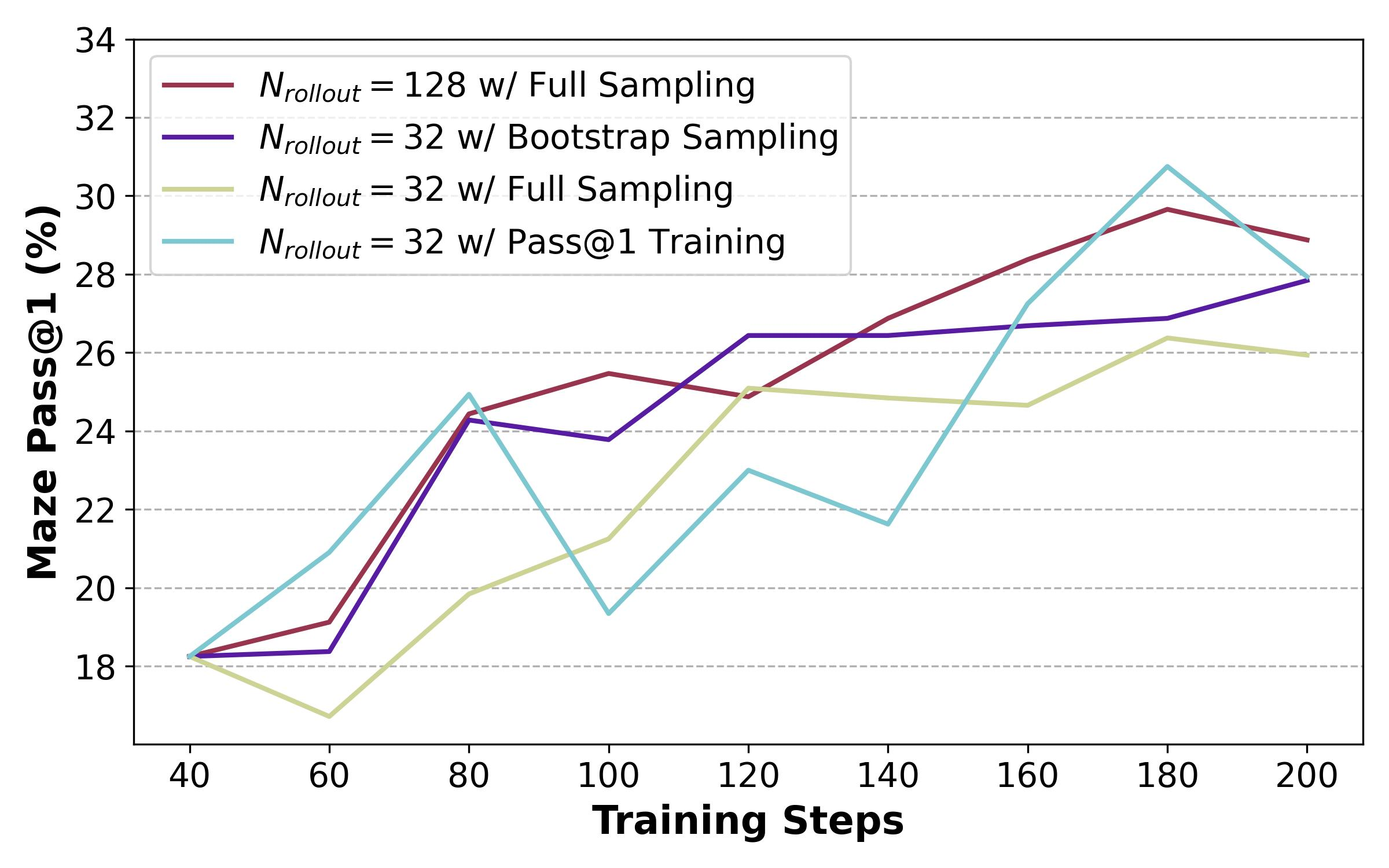

This is not a fringe finding. Research examining six popular RLVR algorithms (PPO, GRPO, Reinforce++, and variants) found they "perform similarly and remain far from optimal in leveraging base model potential."6 The algorithms differ in implementation details but converge on similar outcomes, all bounded by what the base model already knows.

Figure 4: Maze Pass@1 comparison across four training configurations, showing how different RL approaches converge on similar performance levels. Bootstrap sampling with larger rollout counts approaches the performance of computationally expensive full sampling. Source: Pass@k Training

Figure 4: Maze Pass@1 comparison across four training configurations, showing how different RL approaches converge on similar performance levels. Bootstrap sampling with larger rollout counts approaches the performance of computationally expensive full sampling. Source: Pass@k Training

The Exploration-Exploitation Tradeoff

Why does this happen? The mechanism involves how RL training shapes the model's output distribution.

"Pass@1 Training trains LLMs to learn from their exploration and generate the most confident response for the given prompt, leading to a major challenge of the balance of exploration and exploitation."7 The model learns to converge on high-probability correct answers, but this comes at a cost: "while the Pass@1 metric improves in the early stages of training, it stagnates in the later stages, indicating that the model has fallen into a local optimum."8

RL narrows the model's exploration. It learns to favor known high-reward paths rather than discovering new reasoning strategies. The training signal reinforces what works, which means reinforcing patterns the base model already contained.

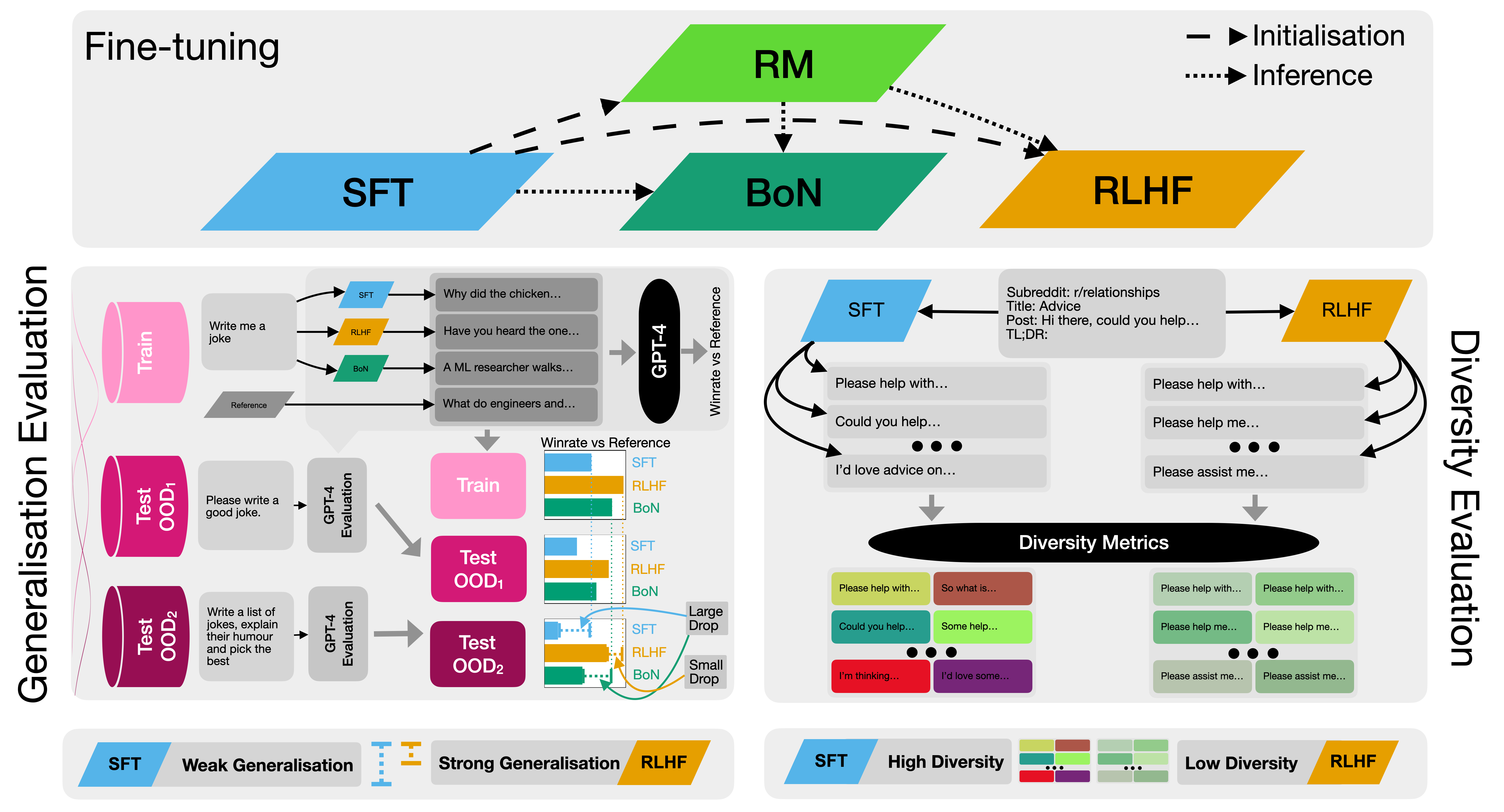

This creates a measurable tradeoff. "RLHF significantly reduces output diversity compared to SFT across a variety of measures, implying a tradeoff in current LLM fine-tuning methods between generalisation and diversity."9 The model becomes more consistent but less creative. It finds correct answers more reliably but explores fewer paths to get there.

Figure 5: Detailed comparison of SFT, Best-of-N (BoN), and RLHF fine-tuning methods, showing training flow and evaluation approaches. Source: Understanding RLHF Generalisation and Diversity

Figure 5: Detailed comparison of SFT, Best-of-N (BoN), and RLHF fine-tuning methods, showing training flow and evaluation approaches. Source: Understanding RLHF Generalisation and Diversity

The Reward Signal Problem

There is another issue: the quality of feedback that RL provides.

Consider what happens during RLVR training on math problems. "The erroneous solution with correct answer will receive positive rewards, while the correct solution with wrong answer will be assigned negative rewards."10 The model can arrive at the right answer through flawed reasoning and get rewarded for it.

This is not a rare edge case. Base models are "capable of producing incorrect CoTs yet coincidentally arriving at the ground truth, especially for hard mathematical questions where answers are simple and can be easily guessed after multiple attempts."11

The problem extends beyond verifiable rewards. Traditional RLHF with learned reward models faces its own challenges. "Our results reveal a reward threshold in PPO training--exceeding it often triggers reward hacking, degrading the model's win rate."12 Models learn to exploit the reward function rather than genuinely improve.

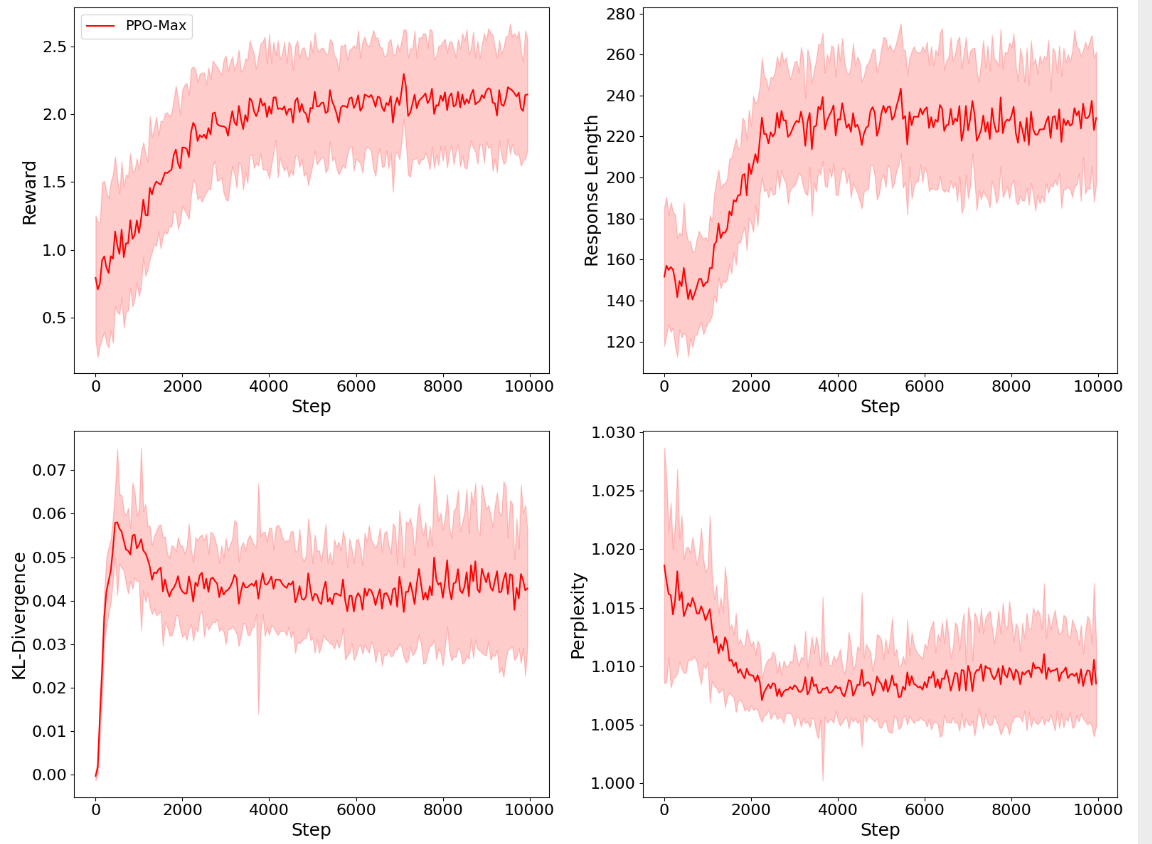

Figure 6: Four-panel view of PPO training metrics over 10K steps showing reward increase alongside response length growth. Note how KL-divergence and perplexity track the distribution shift from the base model. Source: Secrets of RLHF

Figure 6: Four-panel view of PPO training metrics over 10K steps showing reward increase alongside response length growth. Note how KL-divergence and perplexity track the distribution shift from the base model. Source: Secrets of RLHF

Where RLVR Does Work: Search Efficiency

None of this means RLVR is useless. The evidence clearly shows RLVR models outperform base models at pass@1. For deployment scenarios where you serve a single response per query, this matters enormously.

The InstructGPT results demonstrated this convincingly. RLHF training made a smaller model more useful than a much larger base model for typical user interactions. InstructGPT "generates truthful and informative answers about twice as often as GPT-3"13 and produces "about 25% fewer toxic outputs than GPT-3 when prompted to be respectful."14

"RLHF generalises better than SFT to new inputs, particularly as the distribution shift between train and test becomes larger."15 When users interact with deployed models, "the distribution shift is quite pronounced and hence many inputs are more OOD, and this is where RLHF model performance continues to be high."16

These are not trivial improvements. For most production use cases, where users expect a single good response quickly, RLVR-trained models are measurably better.

Wait, That Seems to Contradict the Earlier Findings?

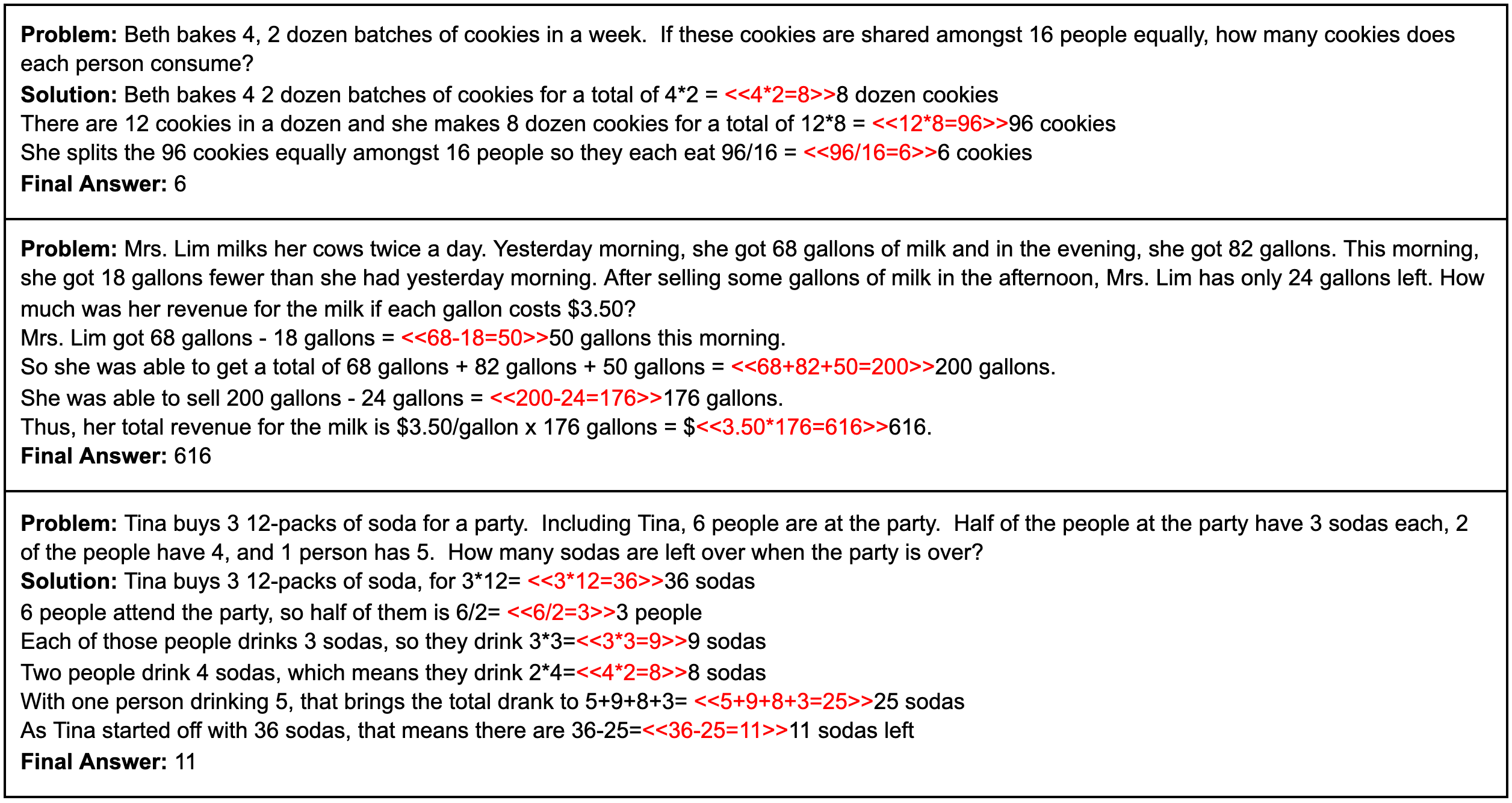

Here's where intellectual honesty requires nuance. A metric called CoT-Pass@K evaluates not just whether the final answer is correct, but whether the intermediate reasoning steps are valid.

"CoT-Pass@K captures reasoning success by accounting for both the final answer and intermediate reasoning steps."17 With this stricter evaluation, "the CoT-Pass@K results on AIME 2024 and AIME 2025 reveal a consistent and significant performance gap between the models across all values of K (up to 1024)."18

The base model catch-up effect partially disappears when you require correct reasoning, not just correct answers. This suggests RLVR may genuinely improve reasoning quality even if it does not expand the space of reachable solutions. The model learns to reason correctly more often, even though it does not learn to reason in new ways.

Figure 7: Example GSM8K problems with step-by-step solutions. Each intermediate calculation builds toward the final answer, showing what chain-of-thought reasoning looks like in practice. Source: Training Verifiers to Solve Math Word Problems

Figure 7: Example GSM8K problems with step-by-step solutions. Each intermediate calculation builds toward the final answer, showing what chain-of-thought reasoning looks like in practice. Source: Training Verifiers to Solve Math Word Problems

The finding aligns with the theoretical intuition that "once LLMs have been pre-trained to establish strong knowledge and logic priors that distinguish correct from incorrect CoTs, the GRPO gradient will increase the probability of generating more correct CoTs."19 RLVR amplifies correct reasoning patterns that already exist, rather than creating new ones.

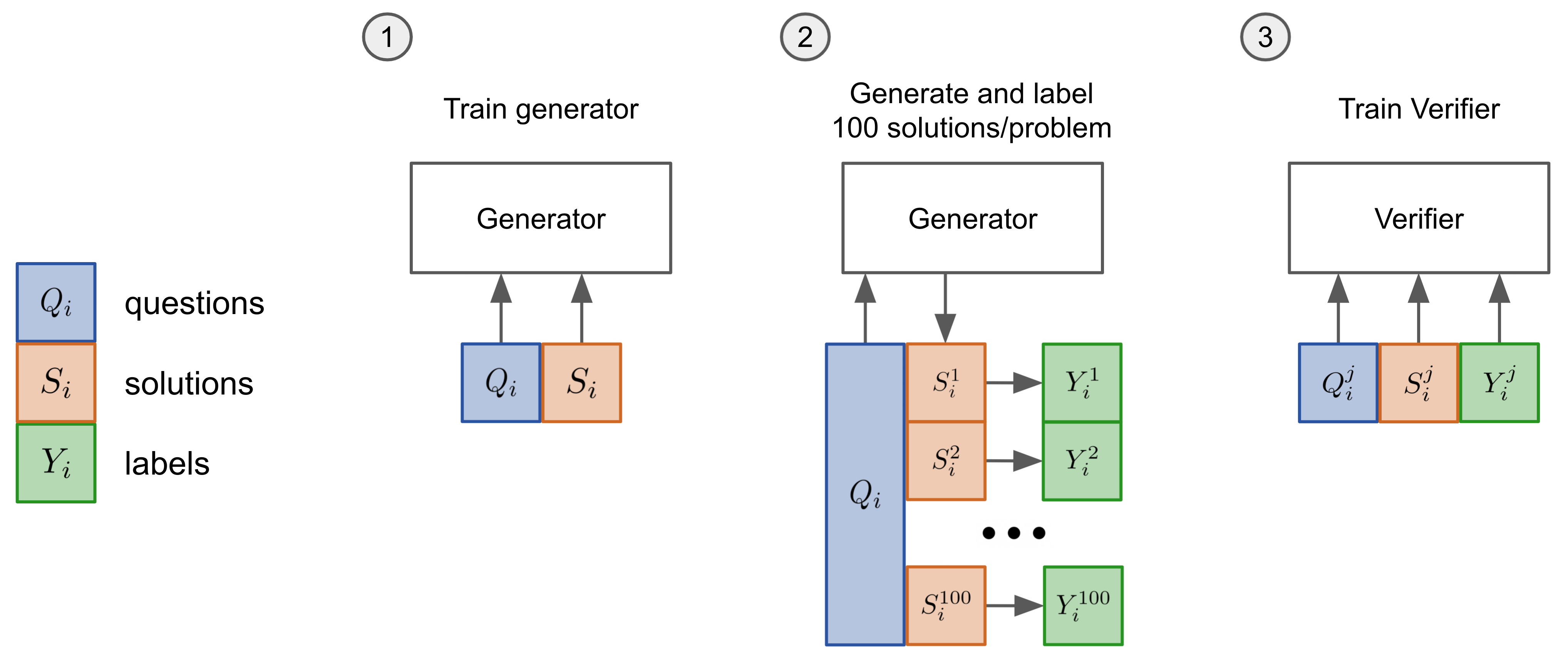

Distillation: The Alternative That Actually Transfers Knowledge

If RLVR optimizes existing capabilities rather than creating new ones, what does create new reasoning abilities?

The evidence points to distillation. Unlike RLVR, distillation can transfer reasoning patterns from teacher to student models that did not previously exist in the student. "Even for distillation models, a high-quality RLVR training recipe can significantly extend the reasoning capability boundary, particularly for competitive coding tasks."20

The mechanism differs in a key way. In distillation, soft targets from the teacher provide richer learning signals than the binary correct/incorrect feedback of RLVR. The student learns not just which answers are right, but how the teacher distributes probability across reasoning steps.

Figure 8: Three-stage training pipeline for verifier-based reasoning improvement, an alternative approach to pure RL. Source: Training Verifiers to Solve Math Word Problems

Figure 8: Three-stage training pipeline for verifier-based reasoning improvement, an alternative approach to pure RL. Source: Training Verifiers to Solve Math Word Problems

Research combining distillation with subsequent RLVR shows the approaches are complementary. "AceReason-Nemotron-7B exhibits clear Pass@K improvements over DeepSeek-R1-Distill-Qwen-7B on most benchmark versions."21 The distilled model starts with transferred reasoning abilities, then RLVR optimizes how efficiently those abilities are deployed.

This suggests a practical hierarchy: distillation for capability transfer, RLVR for inference optimization.

What This Doesn't Mean

A few important caveats before drawing conclusions.

RLVR is not useless. Pass@1 improvements matter for real applications. Most users want good first answers, not optimal performance after 256 samples. The practical efficiency of RLVR models justifies their use in deployment.

Base models are not secretly superhuman. The capability bound is real. Base models have limits, and RLVR-trained models share those limits. RLVR cannot conjure reasoning the base model lacks.

The debate is not settled. Different evaluation metrics tell different stories. CoT-Pass@K shows persistent gaps that standard Pass@K does not. The distinction between "teaching reasoning" and "eliciting latent reasoning" may matter less for practical purposes than for theoretical understanding.

You should not abandon RL post-training. For production deployments with inference compute constraints, RLVR remains highly valuable. The question is what to expect from it.

Implications for Practitioners

What does this mean if you are building or deploying LLMs?

For training decisions: Base model quality matters more than RL algorithm selection. Six different RLVR algorithms produce similar results, all bounded by base model capacity. Invest compute in better pretraining or high-quality distillation rather than elaborate RL pipelines.

For evaluation: Do not rely solely on pass@1 metrics. "Compared to Pass@1 Training, Pass@k Training significantly enhances the exploration ability of LLMs, improving Pass@k performance while not harming Pass@1 scores."22 Evaluate at multiple sampling levels to understand true capability versus search efficiency.

For deployment: RLVR remains valuable when you need a single good response quickly. The pass@1 improvements are real and practically significant. But if your application supports multiple samples (test generation, code completion with suggestions, brainstorming), base model capabilities may matter more.

For robustness: Be cautious about benchmark gains. "LLMs perform far less well when confronted with critical thinking, arithmetic variation, and distractor insertion."23 High accuracy on standard benchmarks does not guarantee robust reasoning on variations.

Honest Caveats

This analysis has important limitations.

First, the pass@k evidence comes primarily from math and coding domains. Whether the pattern holds for general reasoning, multi-step planning, or open-ended tasks remains less clear.

Second, the distinction between "optimizing search" and "improving reasoning" may be less meaningful than it appears. If a model finds correct answers more reliably, does it matter whether the underlying capability is new or better utilized? For most applications, the practical outcome is what counts.

Third, the field is evolving rapidly. "The Logic Prior assumption may not always hold, potentially leading to the reinforcement of incorrect CoTs."24 As understanding of these limitations improves, so may the training methods.

Fourth, some evidence suggests genuine reasoning improvements do occur, particularly on complex reasoning problems. "Only medium and hard problems in LiveCodeBench-v6 contribute to the differentiation between these two models for large K values"25 indicates that task difficulty affects the pattern.

What This Means Going Forward

The evidence suggests RLVR is better understood as an optimization technique than a capability expansion method. It makes models more efficient at deploying reasoning they already possess. It does not teach new ways to think.

This reframing does not diminish RLVR's practical value. Search efficiency matters. For deployed systems serving millions of queries, the difference between needing one sample versus sixteen is enormous. RLVR delivers real, measurable improvements in the scenarios that matter most for production.

But for those hoping RL is the path to more capable reasoning systems, the evidence counsels caution. The reasoning ceiling appears set by pretraining. RLVR helps models approach that ceiling more efficiently, but it does not raise it.

RLVR remains a useful tool. But the next leap in reasoning capability will likely come from advances in pretraining, architecture, or knowledge transfer, not from better reward functions applied to the same base model distributions.

References

Footnotes

-

Yue, Y., Chen, Z., Lu, R., Zhao, A., Wang, Z., Song, S., & Huang, G. (2025). "Does Reinforcement Learning Really Incentivize Reasoning Capacity in LLMs Beyond the Base Model?" NeurIPS 2025 Oral / ICML 2025 AI4MATH Best Paper. arXiv:2504.13837. ↩

-

DeepSeek-AI. (2025). "DeepSeek-R1: Incentivizing Reasoning Capability in LLMs via Reinforcement Learning." arXiv:2501.12948. ↩

-

Ouyang, L., Wu, J., Jiang, X., et al. (2022). "Training language models to follow instructions with human feedback." arXiv:2203.02155. ↩

-

Zhao, A., Yue, Y., Chen, Z., Lu, R., & Huang, G. (2025). "Reinforcement Learning with Verifiable Rewards Implicitly Incentivizes Correct Reasoning in Base LLMs." arXiv:2506.14245. ↩

-

Zhao, A., et al. (2025). arXiv:2506.14245. ↩

-

Yue, Y., et al. (2025). arXiv:2504.13837. ↩

-

Yang, A., Wang, S., et al. (2025). "Pass@k Training for Adaptively Balancing Exploration and Exploitation of Large Reasoning Models." arXiv:2508.10751. ↩

-

Yang, A., et al. (2025). arXiv:2508.10751. ↩

-

Kirk, R., Mediratta, I., Nalmpantis, C., et al. (2023). "Understanding the Effects of RLHF on LLM Generalisation and Diversity." arXiv:2310.06452. ↩

-

Yang, A., et al. (2025). arXiv:2508.10751. ↩

-

Zhao, A., et al. (2025). arXiv:2506.14245. ↩

-

Liu, W., et al. (2025). "Reward Shaping to Mitigate Reward Hacking in RLHF." arXiv:2502.18770. ↩

-

Ouyang, L., et al. (2022). arXiv:2203.02155. ↩

-

Ouyang, L., et al. (2022). arXiv:2203.02155. ↩

-

Kirk, R., et al. (2023). arXiv:2310.06452. ↩

-

Kirk, R., et al. (2023). arXiv:2310.06452. ↩

-

Zhao, A., et al. (2025). arXiv:2506.14245. ↩

-

Zhao, A., et al. (2025). arXiv:2506.14245. ↩

-

Zhao, A., et al. (2025). arXiv:2506.14245. ↩

-

Zhao, A., et al. (2025). arXiv:2506.14245. ↩

-

Zhao, A., et al. (2025). arXiv:2506.14245. ↩

-

Yang, A., et al. (2025). arXiv:2508.10751. ↩

-

Li, Q., Luo, L., et al. (2024). "GSM-Plus: A Comprehensive Benchmark for Evaluating the Robustness of LLMs as Mathematical Problem Solvers." arXiv:2402.19255. ↩

-

Zhao, A., et al. (2025). arXiv:2506.14245. ↩

-

Zhao, A., et al. (2025). arXiv:2506.14245. ↩