When you read the word "Paris," something happens in your mind. You don't just process four letters and five phonemes. You access a web of associations: the Eiffel Tower, croissants, the Seine, perhaps a memory of a trip or a film. You know Paris is west of Berlin, that it existed before you were born, and that walking there from London would require crossing water.

Does GPT-4 do something similar? Or is it, as Emily Bender and colleagues famously argued, merely a "system for haphazardly stitching together sequences of linguistic forms...without any reference to meaning"?1

This question sits at the intersection of cognitive science, philosophy of mind, and AI research. The answer matters not just for understanding machines, but for understanding ourselves.

What Do We Mean by World Models?

Before examining the evidence, we need precision about terms. In cognitive science, a world model is more than a database of facts. It is an internal representation that enables a system to "understand, interpret, and predict phenomena in a way that reflects real-world dynamics, including causality and intuitive physics."2 The neuroscientist Karl Friston's influential framework proposes that brains continuously generate predictions about sensory input and update internal models based on prediction error. This predictive processing view suggests world models are central to cognition itself.

Figure 1: Conceptual diagram showing the relationship between internal world models and external reality. Source: "Grounding Artificial Intelligence in the Origins of Human Behavior"3

Figure 1: Conceptual diagram showing the relationship between internal world models and external reality. Source: "Grounding Artificial Intelligence in the Origins of Human Behavior"3

For LLMs, the question becomes: does training on next-token prediction produce anything resembling this kind of structured, predictive representation? Or does statistical pattern-matching on text, however sophisticated, remain qualitatively different from genuine world modeling?

The Evidence For: Emergent Representations

The most striking evidence comes from a synthetic setting. Researchers trained a GPT variant exclusively on sequences of legal Othello moves, with no information about the game board or rules. The model received only move coordinates like "C4, E3, F5..."

What emerged surprised the researchers: "We find evidence of an emergent world representation in the network: a representation of the board state that is robust, far from trivial, and not simply a lookup table."4

Figure 2: Othello-GPT's internal representation of board state, showing how the model tracks piece positions despite never receiving explicit board information. Source: Li et al., "Emergent World Representations"4

Figure 2: Othello-GPT's internal representation of board state, showing how the model tracks piece positions despite never receiving explicit board information. Source: Li et al., "Emergent World Representations"4

The finding goes beyond correlation. When researchers intervened on the identified world-model neurons, the model's move predictions changed accordingly. "Intervening on the world model can causally affect the model's predictions, providing strong evidence that the model actually uses this internal representation."5 This was not correlation. This was causation.

Similar findings extend to language models trained on natural text. Gurnee and Tegmark demonstrated that "LLaMa has an internal world model of space by showing that LLM's intermediate activation of a location word can be mapped linearly to its physical location."6 The model learns latitude and longitude as linear dimensions in its representation space.

Figure 3: Visualization of LLM's learned geographic representations, showing that models encode spatial relationships from text alone. Source: Gurnee & Tegmark, "Language Models Represent Space and Time"6

Figure 3: Visualization of LLM's learned geographic representations, showing that models encode spatial relationships from text alone. Source: Gurnee & Tegmark, "Language Models Represent Space and Time"6

These are not cherry-picked results. "The distance between the hidden states of city names in the DeBERTa's learned representation space has high correlation with the real-world geospatial distance between cities."7 Causal intervention experiments confirmed these representations matter: "modifying internal hidden states with respect to true city longitudes and latitudes leads to improvement in downstream classification accuracy."8 The spatial representations are not merely stored; they are used.

The Evidence Against: The Grounding Problem Persists

But here is the complication. Even if LLMs encode spatial coordinates, does that constitute understanding geography?

The symbol grounding problem, introduced by Stevan Harnad in 1990, poses the central challenge: "Grounding is the process of connecting abstract knowledge and natural language to the internal representations of our sensorimotor experiences in the real world."9 Without this connection, symbols remain ungrounded, their "meanings" merely pointing to other ungrounded symbols in an endless regress.

The concern is not about capability but about the nature of understanding. "LLMs do not have sensorimotor experiences or feelings as they cannot explore and interact with the real-world environment by themselves."10 This leads to a stark conclusion from some researchers: "The knowledge in LLMs is not grounded like the knowledge in a human brain. Clearly, LLMs do not understand what they do."11

Yann LeCun, Meta's chief AI scientist, has been equally direct, arguing that language alone cannot constitute human-level understanding and that world models must be grounded in multimodal perception and interaction.12

Figure 4: The gap between LLMs as autonomous planners versus LLMs augmented with external verifiers, illustrating the limitations of pure language-based world models for complex reasoning. Source: Valmeekam et al., "On the Planning Abilities of Large Language Models"13

Figure 4: The gap between LLMs as autonomous planners versus LLMs augmented with external verifiers, illustrating the limitations of pure language-based world models for complex reasoning. Source: Valmeekam et al., "On the Planning Abilities of Large Language Models"13

The planning literature adds empirical weight to this skepticism. Critical investigations found that GPT-4 achieves only "approximately 12% success across domains" on commonsense planning tasks.14 If models truly possessed robust world models, shouldn't they plan better?

A Nuanced Middle Ground

Perhaps both extremes miss something. Recent philosophical analysis argues that "LLMs are neither stochastic parrots nor semantic zombies, but already understand the language they generate, at least in an elementary sense."15

This position distinguishes different types of grounding. "Grounding proves to be a gradual affair with a three-dimensional distinction between functional, social and causal grounding."16 By this analysis, "LLMs possess a decent functional, a weak social, and an indirect causal grounding."17

What does indirect causal grounding mean? "LLMs are capable of extracting extensive knowledge about causal and other regularities of the world from vast amounts of textual data through their self-training."18 The grounding is indirect "because the causal chain does not run through direct perceptual or sensorimotor processes, but is mediated by human language data."19

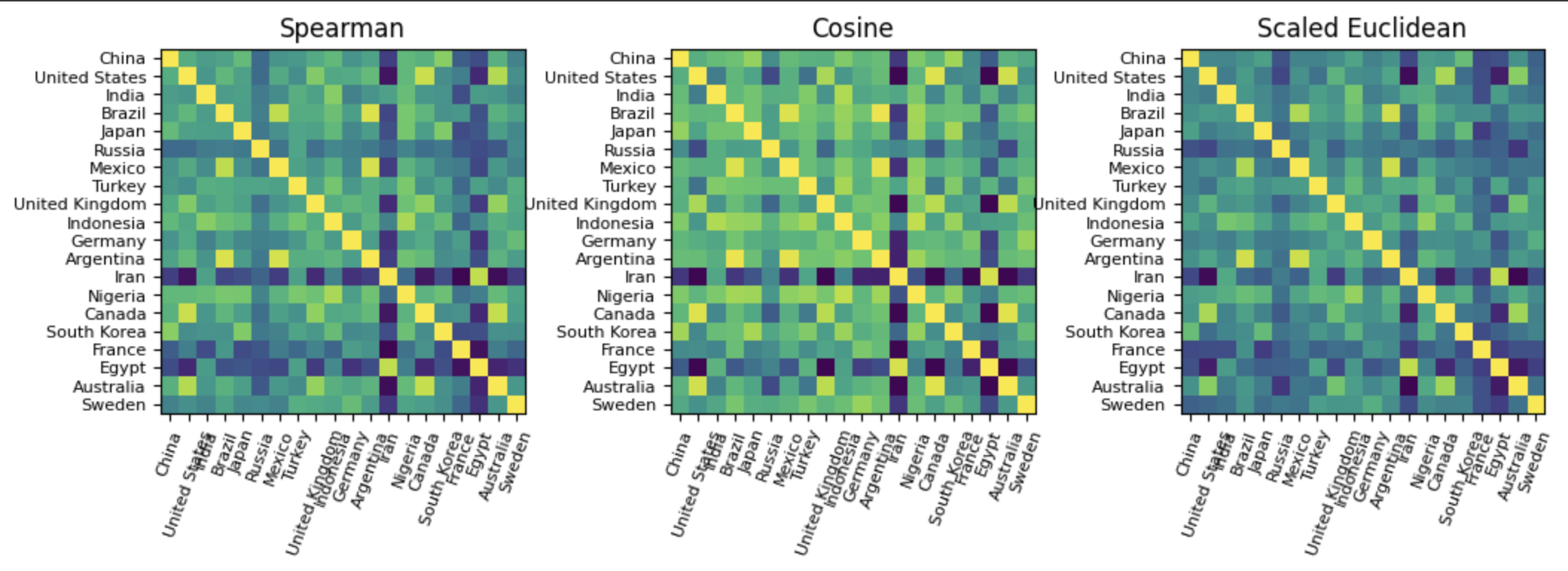

Figure 5: Correlation matrices showing country-level similarity patterns learned by LLMs, revealing geographic and cultural clustering. Source: "More than Correlation: Do Large Language Models Learn Causal Representations of Space?"7

Figure 5: Correlation matrices showing country-level similarity patterns learned by LLMs, revealing geographic and cultural clustering. Source: "More than Correlation: Do Large Language Models Learn Causal Representations of Space?"7

Consider what LLMs can and cannot do:

What they achieve:

- Extracting "extensive knowledge about causal and other regularities of the world from vast amounts of textual data"18

- Developing "world models, i.e. representations that are structurally similar to parts of the world"20

- Showing theory-of-mind capabilities: "Both GPT-4 and already GPT-3.5 have solid Theory-of-Mind-capabilities"21

Where they struggle:

- Autonomous planning, with GPT-4 achieving only approximately 12% success across domains14

- Reliable grounding: "LLMs regularly invent data and false answers, not infrequently in the mode of unbreakable conviction"22

- True embodied understanding of concepts they describe fluently

What This Means for Understanding Cognition

The LLM debate illuminates longstanding questions in cognitive science. If models trained only on text can develop spatial representations, what does this tell us about the relationship between language and thought?

The weak Sapir-Whorf hypothesis holds that language influences thought without determining it. LLM findings suggest something more: that statistical patterns in language encode substantial world structure, enough for models to extract extensive knowledge about causal regularities from text alone.

This does not settle whether language grounds thought or thought grounds language. But it demonstrates that the text-to-world mapping contains more information than pure symbol-grounding skeptics might expect.

For embodied cognition theorists, the challenge is explaining why text-only training produces spatial and temporal representations at all. For computationalists, the challenge is explaining why these representations remain brittle in planning and reasoning tasks.

The philosopher's question "Do LLMs understand?" may be less useful than the cognitive scientist's question "What kind of representations do LLMs develop, and how do they use them?"

Where This Leaves Us

The evidence suggests LLMs develop non-trivial internal representations that encode aspects of world structure. These representations are not merely stored statistics; they are structured, linear, and causally efficacious for model behavior. At the same time, these world models appear incomplete: they support some tasks (spatial reasoning, game playing) better than others (planning, causal intervention).

The philosophical question of whether this constitutes "understanding" may be less important than the empirical question of what these representations can and cannot do. Whether or not we call it understanding, something is going on inside these models that is more interesting than mere pattern matching, and more limited than full human cognition.

The cat sat on the mat. Does an LLM know what that means?

Maybe. A little. In its own strange way.

References

Footnotes

-

Bender, E. M., Gebru, T., McMillan-Major, A., & Mitchell, M. (2021). "On the dangers of stochastic parrots: Can language models be too big?" Proceedings of the 2021 ACM Conference on Fairness, Accountability, and Transparency. ↩

-

Levinstein, B. A., & Herrmann, D. A. (2024). "A Philosophical Introduction to Language Models." arXiv preprint arXiv:2401.03910. ↩

-

"Grounding Artificial Intelligence in the Origins of Human Behavior." (2023). arXiv preprint arXiv:2312.09532. ↩

-

Li, K., Hopkins, A. K., Bau, D., Viegas, F., Pfister, H., & Wiggins, C. (2023). "Emergent world representations: Exploring a sequence model trained on a synthetic task." ICLR 2023. ↩ ↩2

-

Li et al. (2023), ibid. ↩

-

Gurnee, W., & Tegmark, M. (2024). "Language Models Represent Space and Time." arXiv preprint arXiv:2310.02207. ↩ ↩2

-

"More than Correlation: Do Large Language Models Learn Causal Representations of Space?" (2024). arXiv preprint arXiv:2312.16257. ↩ ↩2

-

Ibid. ↩

-

"Grounding Artificial Intelligence in the Origins of Human Behavior." (2023). Lines 42-45. ↩

-

Ibid. Lines 60-62. ↩

-

Ibid. Lines 244-246. ↩

-

LeCun, Y. (2024). Interview: "Meta's AI chief says world models are key to human-level AI." TechCrunch, October 16, 2024. https://techcrunch.com/2024/10/16/metas-ai-chief-says-world-models-are-key-to-human-level-ai-but-it-might-be-10-years-out/ ↩

-

Valmeekam, K., Marques, A., Olmo, A., Sreedharan, S., & Kambhampati, S. (2023). "On the Planning Abilities of Large Language Models: A Critical Investigation." NeurIPS 2023. ↩

-

"Understanding AI: Semantic Grounding in Large Language Models." (2024). arXiv preprint arXiv:2402.10992. Lines 21-23. ↩

-

Ibid. Lines 19-21. ↩

-

Ibid. Lines 99-101. ↩

-

Ibid. Lines 556-559. ↩

-

Ibid. Lines 501-502. ↩

-

Ibid. Lines 293-294. ↩

-

Ibid. Lines 315-316. ↩