DiscoRL: When Algorithms Learn to Design Algorithms

For decades, reinforcement learning algorithms have been handcrafted by researchers. DQN, PPO, A3C: each represents years of iteration, failed experiments, and careful engineering. Every new algorithm requires intuition about what to optimize, how to bootstrap, and which architectural choices will work. But what if we could automate this entire process?

DeepMind's DiscoRL does exactly that. By treating algorithm design as a learning problem, their meta-learning framework discovers RL algorithms that outperform the very algorithms humans spent years designing.1 The implications are striking: we may be entering an era where the role of researchers shifts from designing algorithms to designing the environments and objectives that help algorithms discover themselves.

The Ceiling of Hand-Designed Algorithms

"Reinforcement learning (RL) algorithms update an agent's parameters according to one of several possible rules, discovered manually through years of research."2 This quote from the LPG paper captures the core tension. Despite remarkable progress, hand-designed algorithms face inherent limitations.

Consider the evolution. In 2013, DQN became "the first deep learning model to successfully learn control policies directly from high-dimensional sensory input using reinforcement learning."3 The model was "a convolutional neural network, trained with a variant of Q-learning, whose input is raw pixels and whose output is a value function estimating future rewards."4 It outperformed "all previous approaches on six of the games and surpasses a human expert on three of them."5

PPO followed in 2017, introducing "a novel objective with clipped probability ratios, which forms a pessimistic estimate (i.e., lower bound) of the performance of the policy."6 The result: PPO "outperforms other online policy gradient methods" on standard benchmarks.7

Each improvement came through trial and error. Researchers hypothesized what might work, tested it, and refined based on results. But this process has a fundamental bottleneck: human intuition about what makes a good learning algorithm.

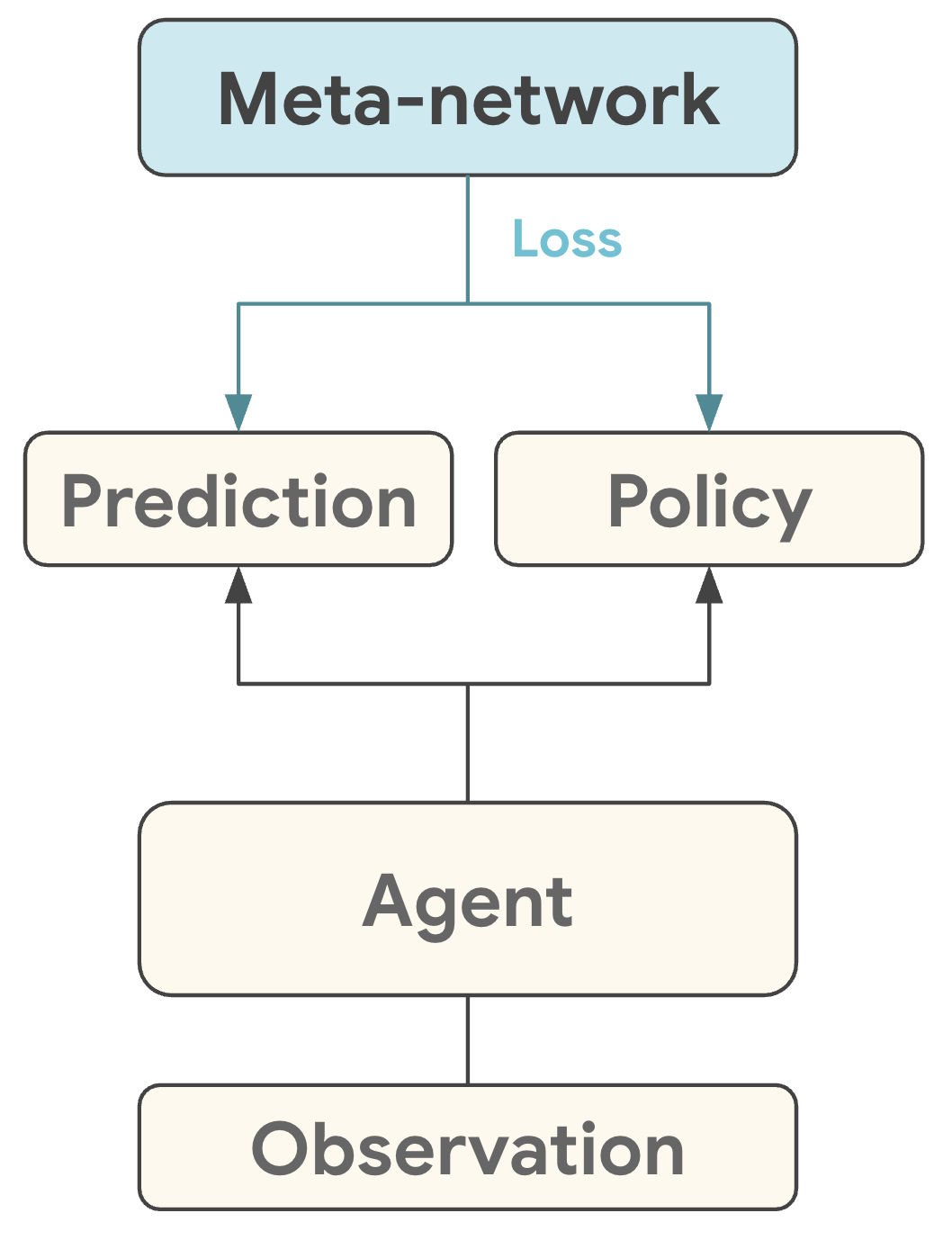

Figure 1: The DiscoRL meta-network architecture. The meta-network learns to produce prediction and policy updates from agent observations, replacing hand-designed update rules with learned ones. Source: Google DeepMind DiscoRL Project

Figure 1: The DiscoRL meta-network architecture. The meta-network learns to produce prediction and policy updates from agent observations, replacing hand-designed update rules with learned ones. Source: Google DeepMind DiscoRL Project

The framework shown above represents a radical departure from traditional algorithm design. Instead of manually specifying what an agent should predict (like value functions) and how it should learn (like TD-learning), the meta-network discovers these components automatically.

What Meta-Learning Actually Does

Meta-learning is often described as "learning to learn," but this phrase obscures more than it reveals. In the context of DiscoRL, meta-learning means optimizing the algorithm itself by measuring how well agents trained with that algorithm perform across many environments.

The progression toward DiscoRL built on years of prior work. MAML established that you could "meta-learn initial parameters by backpropagating through the parameter updates."8 Meta-gradient RL extended this approach to "optimize the choice of bootstrapping and discounting," achieving significant improvements on Atari-57.9

But these approaches still relied on hand-designed algorithmic components. "No prior work has attempted to discover the full update rule; instead they all relied on value functions, arguably the most fundamental building block of RL, for bootstrapping."10

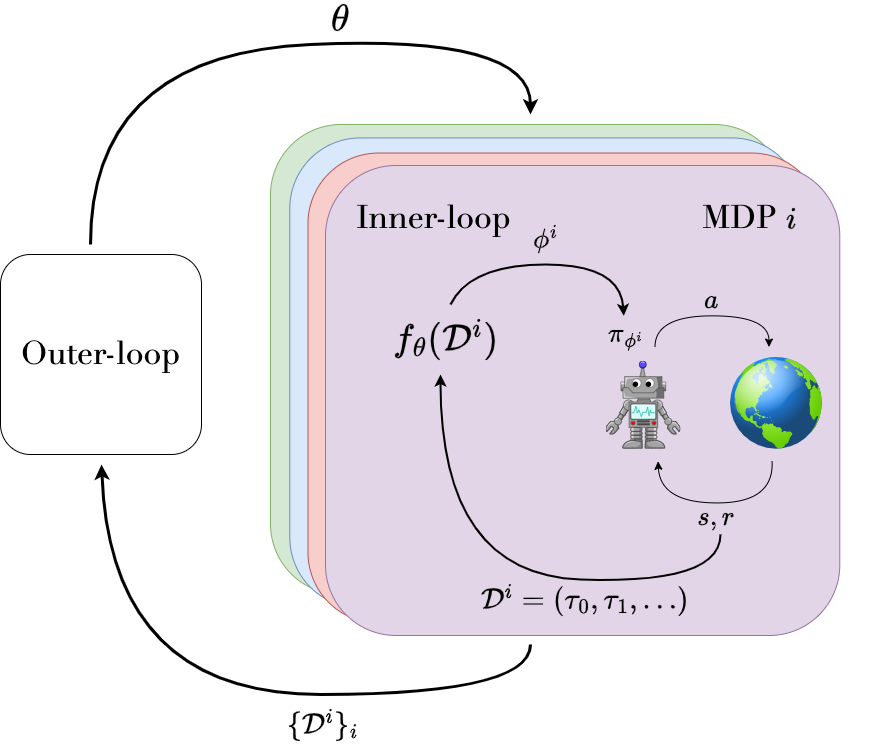

Figure 2: Meta-RL taxonomy showing different approaches to learning learning algorithms. DiscoRL falls under methods that learn the entire update rule, not just initialization or hyperparameters. Source: Beck et al., "A Survey of Meta-Reinforcement Learning" (2023)

Figure 2: Meta-RL taxonomy showing different approaches to learning learning algorithms. DiscoRL falls under methods that learn the entire update rule, not just initialization or hyperparameters. Source: Beck et al., "A Survey of Meta-Reinforcement Learning" (2023)

The LPG paper that preceded DiscoRL took the crucial step: "This paper introduces a new meta-learning approach that discovers an entire update rule which includes both 'what to predict' (e.g. value functions) and 'how to learn from it' (e.g. bootstrapping) by interacting with a set of environments."11

Think of it this way: traditional RL asks "given this algorithm, how well can an agent learn?" Meta-learning inverts the question: "given many agents learning across many tasks, what algorithm produces the best learners?"

The Discovery Pipeline

DiscoRL's approach combines population-based training with meta-learning. The meta-network is a backward LSTM that processes agent experience and outputs how to update the agent's policy and predictions. Specifically, "LPG is a backward LSTM network that produces as output how to update the policy and the prediction vector from the trajectory of the agent."12

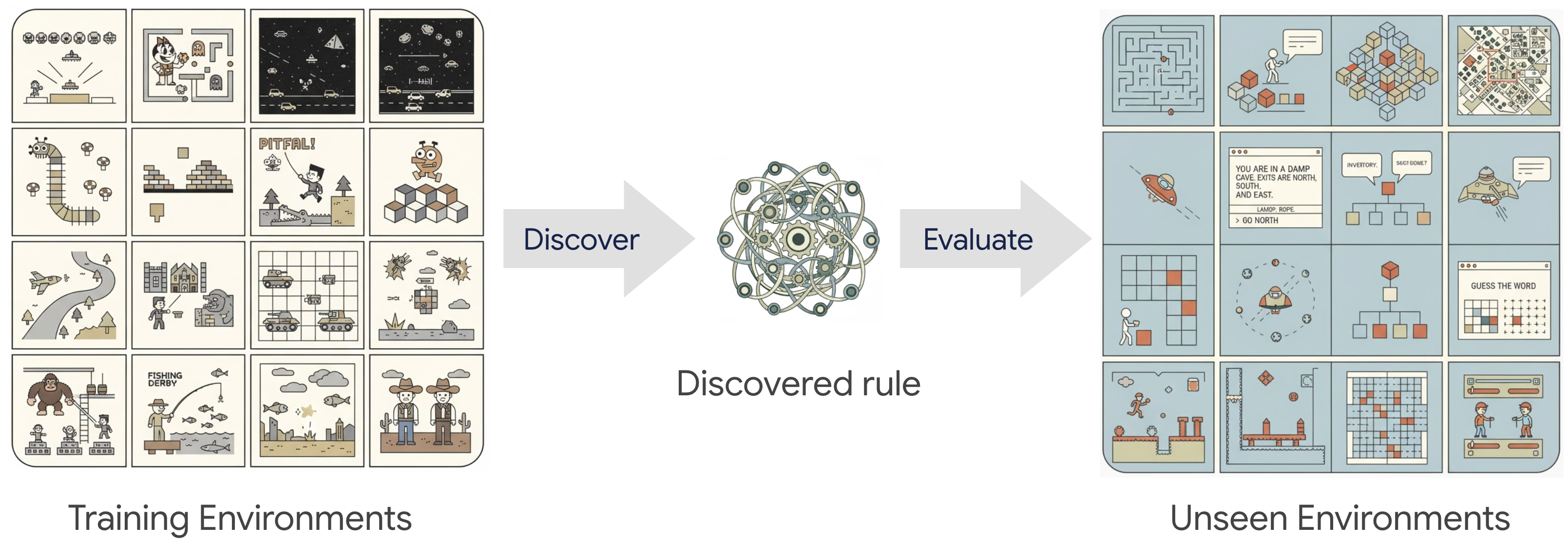

Figure 3: The population-based discovery process. Algorithms are trained on diverse training environments, evaluated on held-out tasks, and the best performers are refined through evolutionary selection. Source: Google DeepMind DiscoRL Project

Figure 3: The population-based discovery process. Algorithms are trained on diverse training environments, evaluated on held-out tasks, and the best performers are refined through evolutionary selection. Source: Google DeepMind DiscoRL Project

A crucial design choice: the meta-network does not see the observation or action spaces directly. "By construction, LPG is invariant to observation space and action space, as it does not take them as input. Instead, it only takes the probability of the chosen action."13 This invariance allows discovered algorithms to generalize across vastly different environments without modification.

The training process works as follows:

- Population initialization: Multiple meta-networks (candidate algorithms) are created

- Inner loop: Each candidate algorithm trains agents on diverse environments

- Evaluation: Agent performance is measured across the environment distribution

- Selection: Best-performing algorithms are kept and refined

- Outer loop: Meta-gradients update the algorithm based on agent performance

"The training environments are designed to capture basic RL challenges such as delayed reward, noisy reward, and long-term credit assignment."14 The training set includes tabular grid worlds with fixed object locations, random grid worlds with randomized layouts, and delayed chain MDPs with delayed rewards.15

The remarkable finding is that algorithms discovered on these toy tasks generalize to much more complex domains.

What Did It Discover?

Perhaps the most surprising finding is that the discovered algorithm develops its own alternative to value functions. "Empirical results show that our method discovers its own alternative to the concept of value functions. Furthermore it discovers a bootstrapping mechanism to maintain and use its predictions."16

The meta-network uses a 30-dimensional prediction vector rather than a scalar value function: "We used a 30-dimensional prediction vector y in [0,1]^30."17 This richer representation enables more nuanced credit assignment than traditional value functions.

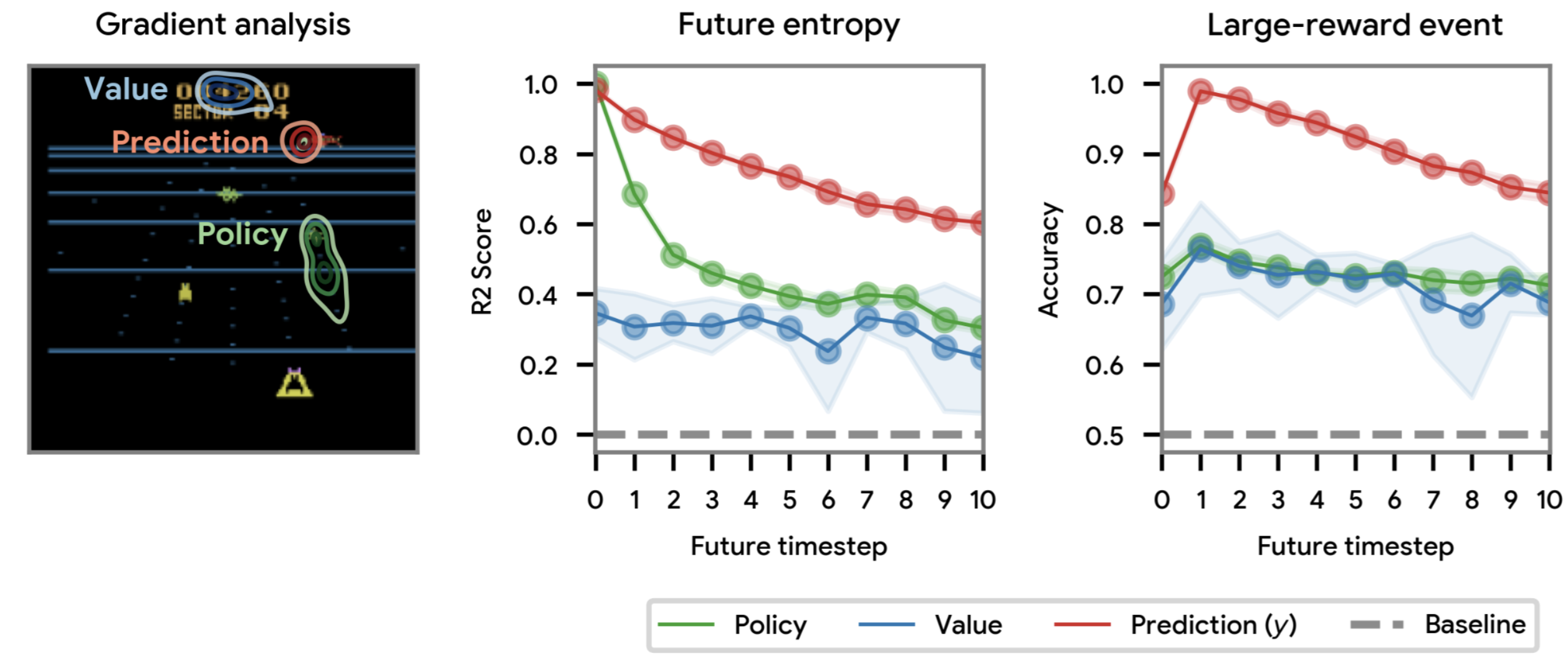

Figure 4: Analysis of the discovered prediction semantics. The learned predictions exhibit value-function-like properties, with values propagating from rewarding states to nearby states. Source: Google DeepMind DiscoRL Project

Figure 4: Analysis of the discovered prediction semantics. The learned predictions exhibit value-function-like properties, with values propagating from rewarding states to nearby states. Source: Google DeepMind DiscoRL Project

When researchers analyzed these learned predictions, they found something remarkable: "the value regression from y is almost as good as TD(lambda) at the original discount factor (0.995) as updated by the LPG, which implies that the information in y is rich enough to recover the original concept of value function."18

In other words, the algorithm discovered something functionally equivalent to value functions, but through optimization rather than human design. It also discovered bootstrapping, one of the most fundamental techniques in RL. The algorithm was not told to bootstrap. It learned that bootstrapping works.

Even more interesting: "two different prediction vectors (y0, y1) converge to almost the same values when updated by the LPG. This implies that a stationary semantics, to which predictions converge, has naturally emerged from the proposed framework."19 The algorithm finds stable, useful representations without being told what to represent.

Benchmark Results

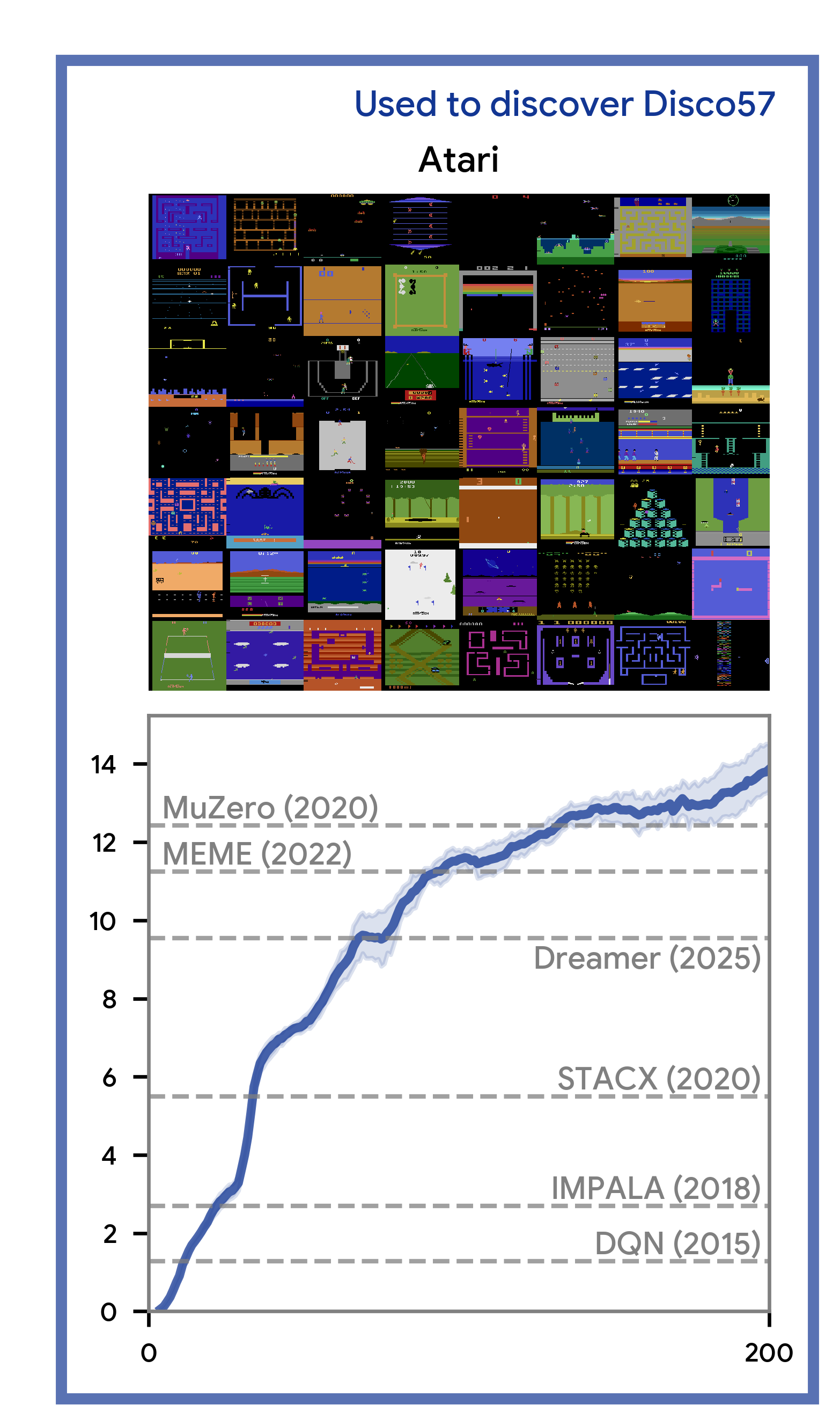

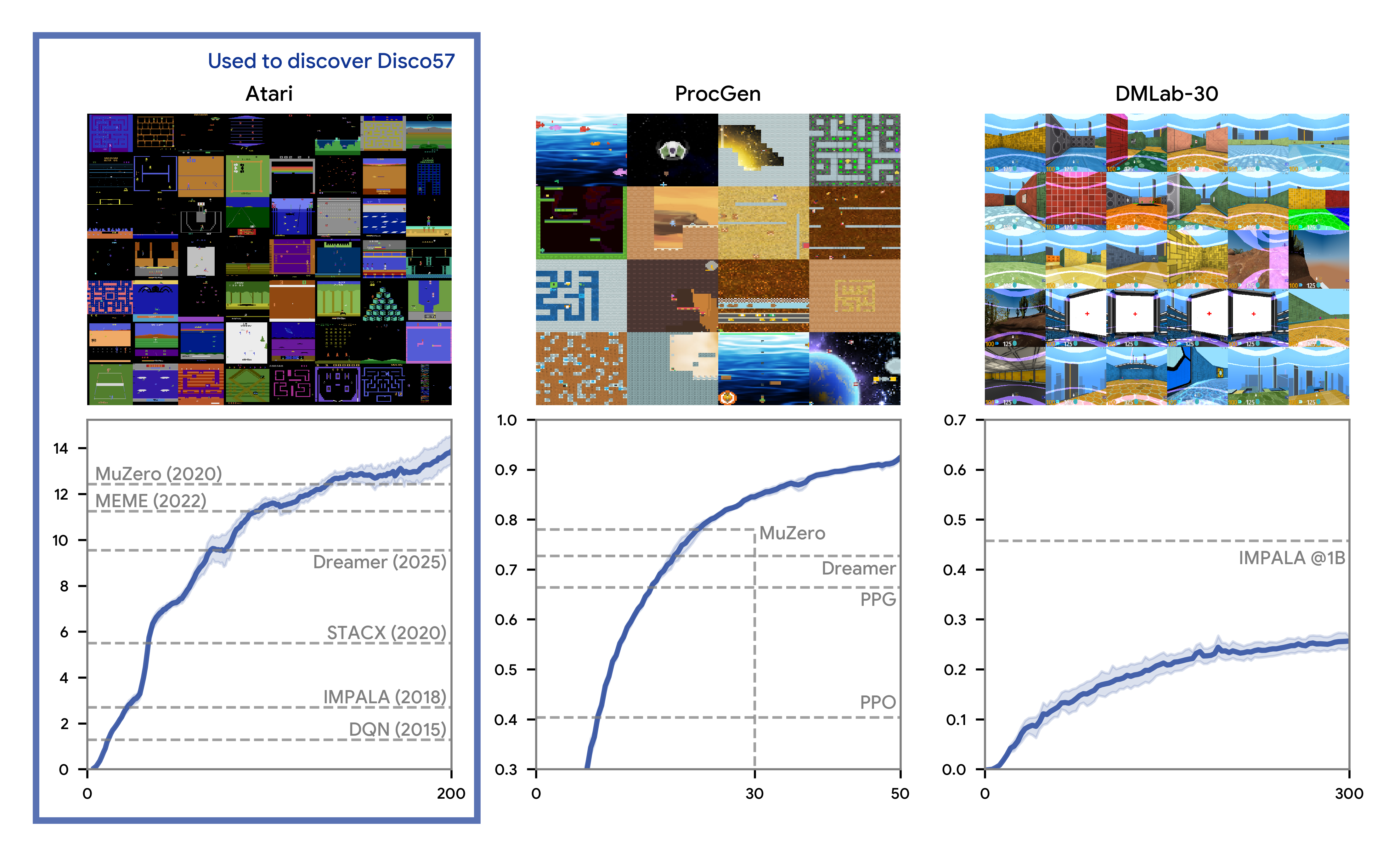

The proof is in the benchmarks. DiscoRL was evaluated against state-of-the-art hand-designed algorithms across three major benchmark suites: Atari57, ProcGen, and DMLab-30.

Figure 5: Performance on Atari57 showing DiscoRL's discovered algorithm (Disco57) compared to prior methods including DQN (2015), IMPALA (2018), STACX (2020), Dreamer (2020), MEME (2022), and MuZero (2020). The discovered algorithm matches or exceeds carefully engineered baselines. Source: Google DeepMind DiscoRL Project

Figure 5: Performance on Atari57 showing DiscoRL's discovered algorithm (Disco57) compared to prior methods including DQN (2015), IMPALA (2018), STACX (2020), Dreamer (2020), MEME (2022), and MuZero (2020). The discovered algorithm matches or exceeds carefully engineered baselines. Source: Google DeepMind DiscoRL Project

The results show that algorithms discovered through meta-learning can match or exceed decades of hand-engineering. "The agents trained with the LPG can learn complex behaviours across many Atari games achieving super-human performance on 14 games, without relying on any hand-designed RL components such as value function."20

To appreciate this, consider what PPO represents: years of research building on TRPO, actor-critic methods, and variance reduction techniques. "The new methods, which we call proximal policy optimization (PPO), have some of the benefits of trust region policy optimization (TRPO), but they are much simpler to implement, more general, and have better sample complexity."21 Yet a discovered algorithm, trained only on toy environments, achieves competitive or better performance.

Figure 6: Generalization results on ProcGen (procedurally generated games) and DMLab-30 (3D cognitive tasks). The discovered algorithm shows robust performance across diverse task types, not just the Atari games traditionally used for RL evaluation. Source: Google DeepMind DiscoRL Project

Figure 6: Generalization results on ProcGen (procedurally generated games) and DMLab-30 (3D cognitive tasks). The discovered algorithm shows robust performance across diverse task types, not just the Atari games traditionally used for RL evaluation. Source: Google DeepMind DiscoRL Project

The ProcGen and DMLab results are particularly important. ProcGen was introduced as "a suite of 16 procedurally generated game-like environments designed to benchmark both sample efficiency and generalization in reinforcement learning."22 This prevents algorithms from memorizing specific solutions. Researchers found that "agents strongly overfit to small training sets in almost all cases. To close the generalization gap, agents need access to as many as 10,000 levels."23

Strong performance across all three benchmark suites suggests the discovered algorithm captures something fundamental about learning, not just tricks that work on specific games.

The Generalization Puzzle

The most striking result is generalization. "Surprisingly, when trained solely on toy environments, LPG generalises effectively to complex Atari games and achieves non-trivial performance."24

This should not work. The training environments were simple grid worlds and chain MDPs. Atari games have high-dimensional visual inputs (210x160 RGB at 60Hz), complex dynamics, and diverse reward structures.25 How does an algorithm discovered on toy tasks transfer to this complexity?

The answer lies in what the meta-learning objective actually optimizes. The algorithm is not learning features of specific environments. It is learning what makes learning effective in general. "The goal of the proposed meta-learning framework is to find the optimal update rule, parameterised by eta, from a distribution of environments p(E) and initial agent parameters p(theta_0)."26

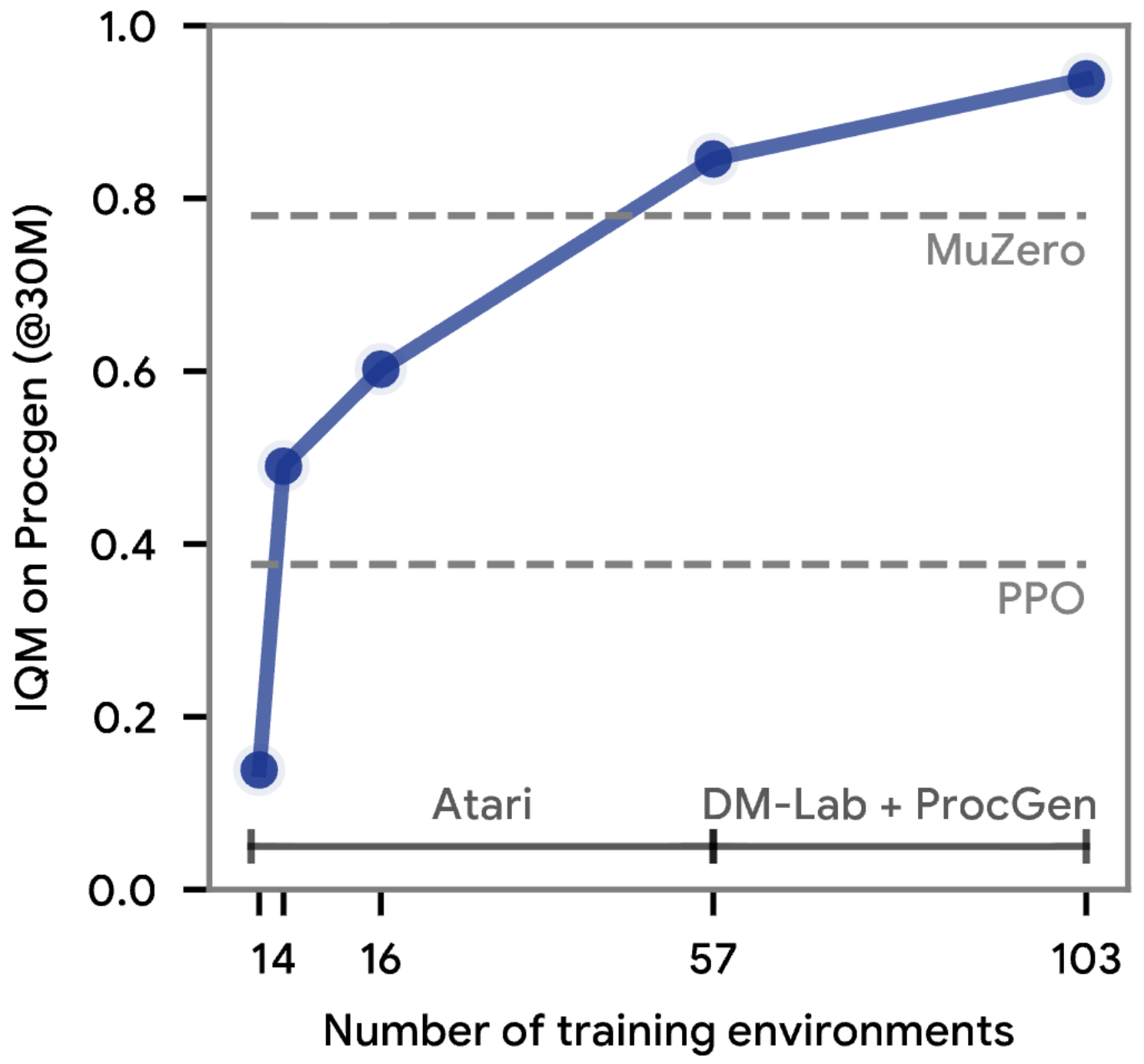

Figure 7: Scaling analysis showing how discovered algorithm performance improves with training environment diversity. More diverse training leads to better generalization, suggesting the meta-learning process extracts increasingly general learning principles. Source: Google DeepMind DiscoRL Project

Figure 7: Scaling analysis showing how discovered algorithm performance improves with training environment diversity. More diverse training leads to better generalization, suggesting the meta-learning process extracts increasingly general learning principles. Source: Google DeepMind DiscoRL Project

The scaling analysis reveals an important trend: "the generalisation performance improves quickly as the number of training environments grows, which suggests that it may be feasible to discover a general-purpose RL algorithm once a larger set of environments are available for meta-training."27

This has practical implications. We might not need researchers to design algorithms for new domains. Instead, we need diverse training environments that expose algorithms to the full range of learning challenges.

What We Still Do Not Understand

Honesty requires acknowledging what remains unclear. The discovered algorithm works, but we do not fully understand why.

One hypothesis is that meta-learning finds algorithms robust to environment variation. "We found that specific types of training environments, such as delayed chain MDPs, significantly improved the generalisation performance."28 This suggests certain training challenges are particularly important for discovering general algorithms.

The comparison between LPG and its ablation LPG-V (which used standard value functions) is instructive: "LPG-V is much worse than LPG while not clearly better than A2C. This shows that discovering the semantics of prediction is the key for the performance."29 Allowing the algorithm to discover what to predict, not just how to learn from predictions, is crucial. But what makes the discovered predictions better than hand-designed value functions?

We can say: "This result supports our hypothesis that discovering alternatives to value functions has the greater potential to find better update rules, although optimisation can be more difficult."30 The potential is demonstrated. The mechanism remains partially opaque.

Implications for the Field

"The proposed approach has a potential to dramatically accelerate the process of discovering new reinforcement learning (RL) algorithms by automating the process of discovery in a data-driven way."31 But what does this actually mean for practitioners and researchers?

For practitioners, several implications emerge:

-

Algorithm selection may become automated: Instead of choosing between PPO, SAC, or DQN, you might run algorithm discovery on your task distribution.

-

Domain-specific algorithms become feasible: Training DiscoRL on environments matching your domain could yield algorithms optimized for your specific challenges.

-

Hyperparameter tuning shifts to environment design: The quality of discovered algorithms depends heavily on training environment diversity. Engineers might focus less on tuning algorithm parameters and more on curating environment distributions.

-

Interpretability becomes harder: Hand-designed algorithms are interpretable by construction. We know what PPO's clipping does because we designed it that way. Discovered algorithms are partially opaque.

For researchers, the implications are more immediate. "If the proposed research direction succeeds, this could shift the research paradigm from manually developing RL algorithms to building a proper set of environments so that the resulting algorithm is efficient."32

This parallels what happened in computer vision and NLP. Researchers used to hand-design features. Now they design architectures and training procedures that learn features. DiscoRL suggests a similar transition in RL: from designing algorithms to designing the meta-learning setup that discovers algorithms.

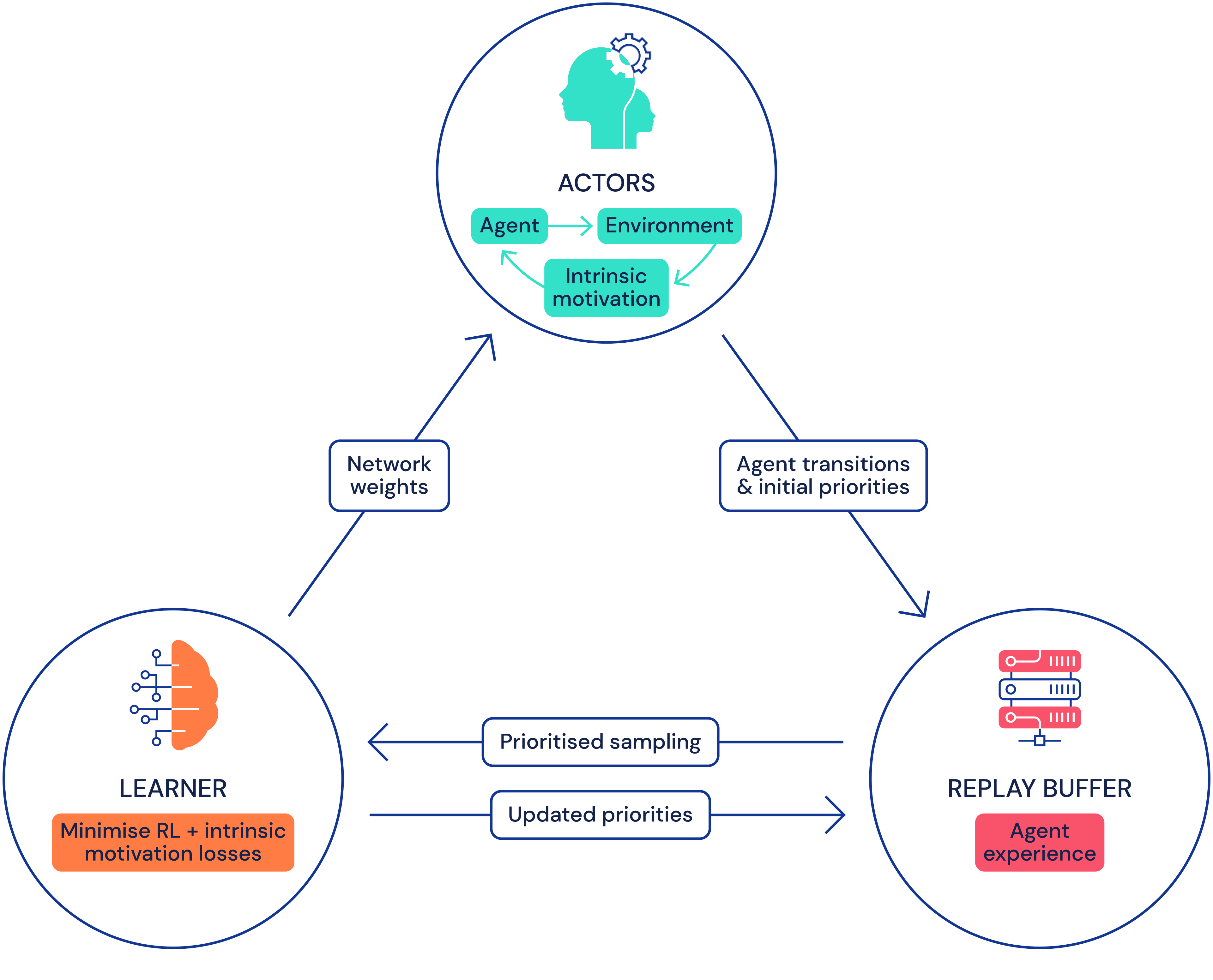

Figure 8: Distributed RL training architecture showing actors, learner, and replay buffer interactions. DiscoRL builds on this infrastructure to enable population-based meta-learning at scale. Understanding the computational demands helps contextualize why algorithm discovery has only recently become feasible. Source: DeepMind Agent57 Blog (2020)

Figure 8: Distributed RL training architecture showing actors, learner, and replay buffer interactions. DiscoRL builds on this infrastructure to enable population-based meta-learning at scale. Understanding the computational demands helps contextualize why algorithm discovery has only recently become feasible. Source: DeepMind Agent57 Blog (2020)

The computational requirements are substantial. Training with PPO on a single ProcGen environment "requires approximately 24 GPU-hrs and 60 CPU-hrs."33 DiscoRL's population-based meta-learning adds another layer of computational demand on top of this infrastructure.

Conclusion

For decades, designing RL algorithms required deep expertise, intuition, and years of iteration. PPO emerged from TRPO which emerged from natural gradient methods which built on policy gradient theory. Each step represented substantial human effort.

DiscoRL demonstrates another path. Instead of designing algorithms, we can design the learning process that discovers algorithms. "This paper made the first attempt to meta-learn a full RL update rule by jointly discovering both 'what to predict' and 'how to bootstrap', replacing existing RL concepts such as value function and TD-learning."34

"This is the first to show that it is possible to discover an entire update rule, and that the update rule discovered from toy domains can be competitive with human-designed algorithms on a challenging benchmark."35 The concepts we thought were fundamental to RL turn out to be discoverable.

The potential is captured well: "This shows the potential to discover general RL algorithms from data."36 And as the authors note, "We believe this is just the beginning of the fully data-driven discovery of RL algorithms; there are many promising directions to extend our work."37

The question is no longer "what is the best RL algorithm?" It is "what environments should we use to discover one?"

References

Footnotes

-

Oh, J. et al. "Discovering state-of-the-art reinforcement learning algorithms." Nature (2025). https://www.nature.com/articles/s41586-025-09761-x ↩

-

Oh, J. et al. "Discovering Reinforcement Learning Algorithms." NeurIPS 2020. Lines 7-8. ↩

-

Mnih, V. et al. "Playing Atari with Deep Reinforcement Learning." arXiv:1312.5602 (2013). Lines 8-9. ↩

-

Mnih, V. et al. "Playing Atari with Deep Reinforcement Learning." arXiv:1312.5602 (2013). Lines 10-11. ↩

-

Mnih, V. et al. "Playing Atari with Deep Reinforcement Learning." arXiv:1312.5602 (2013). Lines 13-15. ↩

-

Schulman, J. et al. "Proximal Policy Optimization Algorithms." arXiv:1707.06347 (2017). Lines 32-33. ↩

-

Schulman, J. et al. "Proximal Policy Optimization Algorithms." arXiv:1707.06347 (2017). Lines 15-17. ↩

-

Oh, J. et al. "Discovering Reinforcement Learning Algorithms." NeurIPS 2020. Lines 81-82. ↩

-

Xu, Z., van Hasselt, H., & Silver, D. "Meta-Gradient Reinforcement Learning." NeurIPS 2018. ↩

-

Oh, J. et al. "Discovering Reinforcement Learning Algorithms." NeurIPS 2020. Lines 103-104. ↩

-

Oh, J. et al. "Discovering Reinforcement Learning Algorithms." NeurIPS 2020. Lines 14-16. ↩

-

Oh, J. et al. "Discovering Reinforcement Learning Algorithms." NeurIPS 2020. Lines 144-145. ↩

-

Oh, J. et al. "Discovering Reinforcement Learning Algorithms." NeurIPS 2020. Lines 148-150. ↩

-

Oh, J. et al. "Discovering Reinforcement Learning Algorithms." NeurIPS 2020. Lines 260-261. ↩

-

Oh, J. et al. "Discovering Reinforcement Learning Algorithms." NeurIPS 2020. Lines 257-259. ↩

-

Oh, J. et al. "Discovering Reinforcement Learning Algorithms." NeurIPS 2020. Lines 18-19. ↩

-

Oh, J. et al. "Discovering Reinforcement Learning Algorithms." NeurIPS 2020. Line 264. ↩

-

Oh, J. et al. "Discovering Reinforcement Learning Algorithms." NeurIPS 2020. Lines 383-385. ↩

-

Oh, J. et al. "Discovering Reinforcement Learning Algorithms." NeurIPS 2020. Lines 398-401. ↩

-

Oh, J. et al. "Discovering Reinforcement Learning Algorithms." NeurIPS 2020. Lines 517-519. ↩

-

Schulman, J. et al. "Proximal Policy Optimization Algorithms." arXiv:1707.06347 (2017). Lines 12-15. ↩

-

Cobbe, K. et al. "Leveraging Procedural Generation to Benchmark Reinforcement Learning." ICML 2020. Lines 5-7. ↩

-

Cobbe, K. et al. "Leveraging Procedural Generation to Benchmark Reinforcement Learning." ICML 2020. Lines 253-255. ↩

-

Oh, J. et al. "Discovering Reinforcement Learning Algorithms." NeurIPS 2020. Lines 20-21. ↩

-

Mnih, V. et al. "Playing Atari with Deep Reinforcement Learning." arXiv:1312.5602 (2013). Lines 55-57. ↩

-

Oh, J. et al. "Discovering Reinforcement Learning Algorithms." NeurIPS 2020. Lines 127-129. ↩

-

Oh, J. et al. "Discovering Reinforcement Learning Algorithms." NeurIPS 2020. Lines 528-530. ↩

-

Oh, J. et al. "Discovering Reinforcement Learning Algorithms." NeurIPS 2020. Lines 520-521. ↩

-

Oh, J. et al. "Discovering Reinforcement Learning Algorithms." NeurIPS 2020. Lines 325-327. ↩

-

Oh, J. et al. "Discovering Reinforcement Learning Algorithms." NeurIPS 2020. Lines 509-510. ↩

-

Oh, J. et al. "Discovering Reinforcement Learning Algorithms." NeurIPS 2020. Lines 545-546. ↩

-

Oh, J. et al. "Discovering Reinforcement Learning Algorithms." NeurIPS 2020. Lines 547-549. ↩

-

Cobbe, K. et al. "Leveraging Procedural Generation to Benchmark Reinforcement Learning." ICML 2020. Lines 137-139. ↩

-

Oh, J. et al. "Discovering Reinforcement Learning Algorithms." NeurIPS 2020. Lines 535-537. ↩

-

Oh, J. et al. "Discovering Reinforcement Learning Algorithms." NeurIPS 2020. Lines 71-73. ↩

-

Oh, J. et al. "Discovering Reinforcement Learning Algorithms." NeurIPS 2020. Line 22. ↩

-

Oh, J. et al. "Discovering Reinforcement Learning Algorithms." NeurIPS 2020. Lines 539-540. ↩