When 62 Days of Compute Becomes 3: Diffusion Models as Fast Surrogates for Agent-Based Biological Simulations

Running a single Cellular Potts Model simulation of vasculogenesis takes about 7 minutes on a modern workstation. That sounds acceptable until you need to explore a parameter space with 25 different configurations, running 5,100 simulations per configuration to capture the stochastic variation. The math gets uncomfortable fast: you're looking at 127,500 simulations and roughly 62 days of compute time.

This is the computational reality facing researchers who use agent-based models to study tissue formation, organ development, and other emergent biological phenomena. As Comlekoglu and colleagues note, "Mechanistic, multicellular, agent-based models are commonly used to investigate tissue, organ, and organism-scale biology at single-cell resolution" [1]. The models are powerful precisely because they capture emergent phenomena arising from individual cell behaviors. But that power comes at a cost.

A recent paper from the University of Virginia and Indiana University offers a compelling solution: train a denoising diffusion probabilistic model (DDPM) to generate cell configurations directly, bypassing the expensive step-by-step simulation entirely. Their approach achieves "approximately a 22x reduction in computational time" while producing configurations that an image classifier cannot reliably distinguish from real simulation outputs [1]. This isn't about replacing mechanistic understanding with black-box prediction. It's about creating fast surrogates that enable the parameter exploration workflows that computational biology desperately needs.

The Cellular Potts Model: Powerful but Computationally Hungry

Before examining the surrogate approach, it helps to understand what makes CPMs both valuable and expensive. "The Cellular-Potts model is a stochastic mathematical framework that allows for agent-based modeling of complex biological systems such as cells and tissues" [1]. Originally proposed for cell sorting by Graner and Glazier in 1992, the CPM "has since been extended with a plethora of biological processes" including "vasculogenesis, skeletal muscle regeneration, and embryonic development" [1].

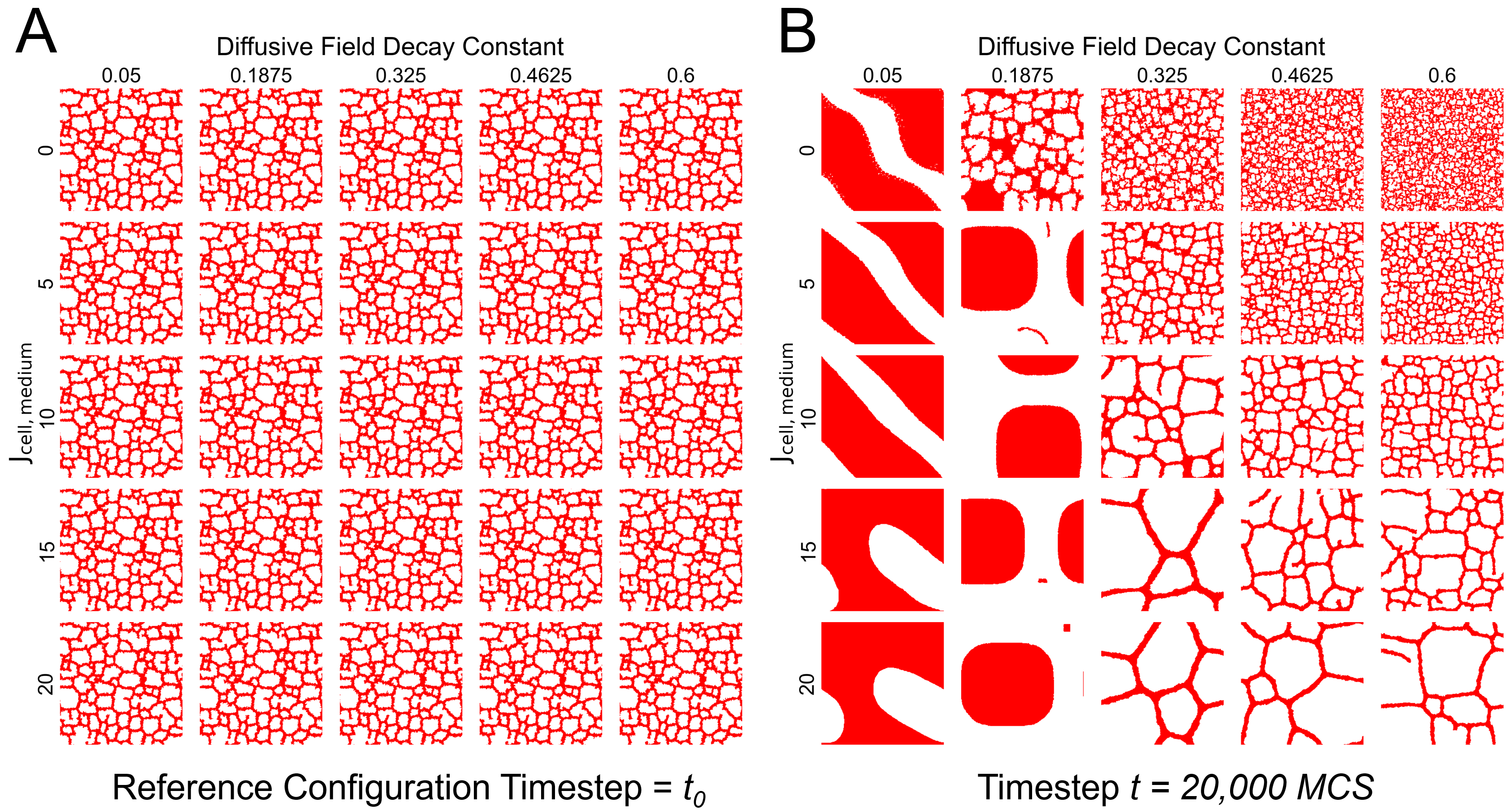

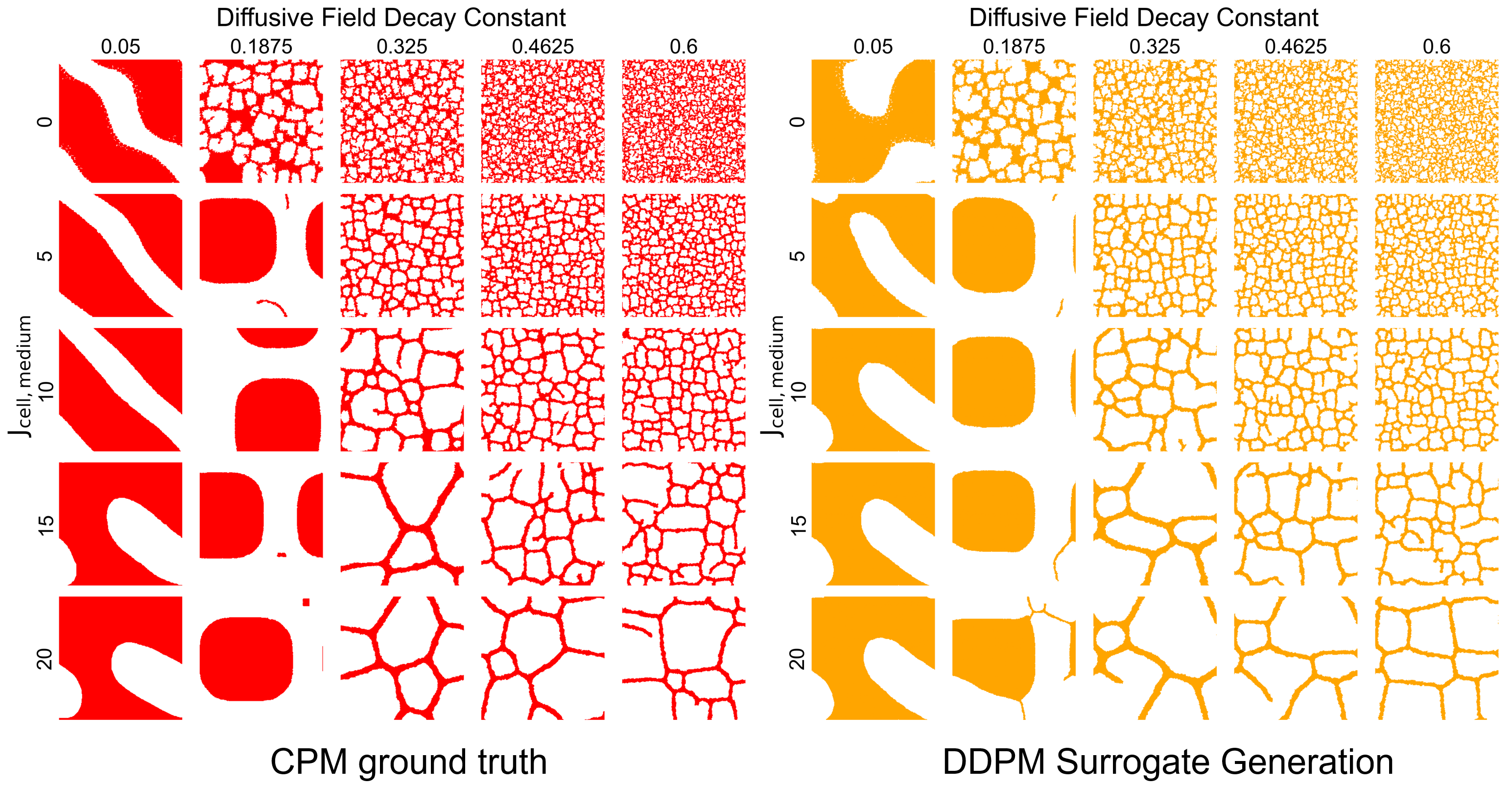

Figure 1: Cellular Potts Model simulations across different parameter combinations, showing diverse tissue morphologies from confluent sheets to sparse vascular networks. Rows vary cell-medium adhesion energy while columns vary the diffusive field decay constant. Source: Generative Diffusion Model Surrogates for Agent-Based Biological Models

Figure 1: Cellular Potts Model simulations across different parameter combinations, showing diverse tissue morphologies from confluent sheets to sparse vascular networks. Rows vary cell-medium adhesion energy while columns vary the diffusive field decay constant. Source: Generative Diffusion Model Surrogates for Agent-Based Biological Models

Figure 1 illustrates the challenge beautifully. Each column represents a different decay constant for the chemical field that guides cell movement, while each row represents different adhesion energies between cells and their medium. The biological outcomes range from confluent tissue sheets (upper left) to sparse vascular networks (lower right). Understanding which parameters produce which phenotypes requires systematic exploration of this space.

At the algorithmic level, "at each MCS or computational timestep, the CPM model creates cell movement by selecting random pairs of neighboring voxels and evaluating whether one voxel may copy itself to its neighbor" [1]. For the vasculogenesis model used in this work, "approximately 1000 CPM cell agents were placed randomly throughout the 256x256 simulation domain" [1]. The stochastic nature of these simulations creates a unique challenge: "the stochastic nature of these models means each set of parameters may give rise to different model configurations, complicating surrogate model development" [1].

You cannot simply learn a mapping from parameters to a single output configuration because the same parameters produce different configurations on each run. You need to learn the distribution of possible outputs.

Why Diffusion Models Fit This Problem

The obvious approach might be a deterministic neural network like U-Net. In fact, related work from the same research group demonstrates a U-Net surrogate achieving "accelerating simulation evaluations by a factor of 562 times compared to single-core CPM code execution" [2]. That's more than 25 times faster than the diffusion approach.

So why bother with diffusion models?

The answer lies in that fundamental stochasticity. "Convolutional neural networks such as the U-Net are deterministic models and therefore lack the ability to replicate the stochastic nature of the CPM simulation" [2]. A U-Net gives you one answer per input. But CPM produces a distribution of possible answers, and that distribution matters for understanding biological variability. The researchers explicitly acknowledge this: "Deep generative modeling approaches such as variational autoencoders, normalizing flows, or generative denoising diffusion models may be better suited to capture the stochastic behaviors of the CPM methodology" [2].

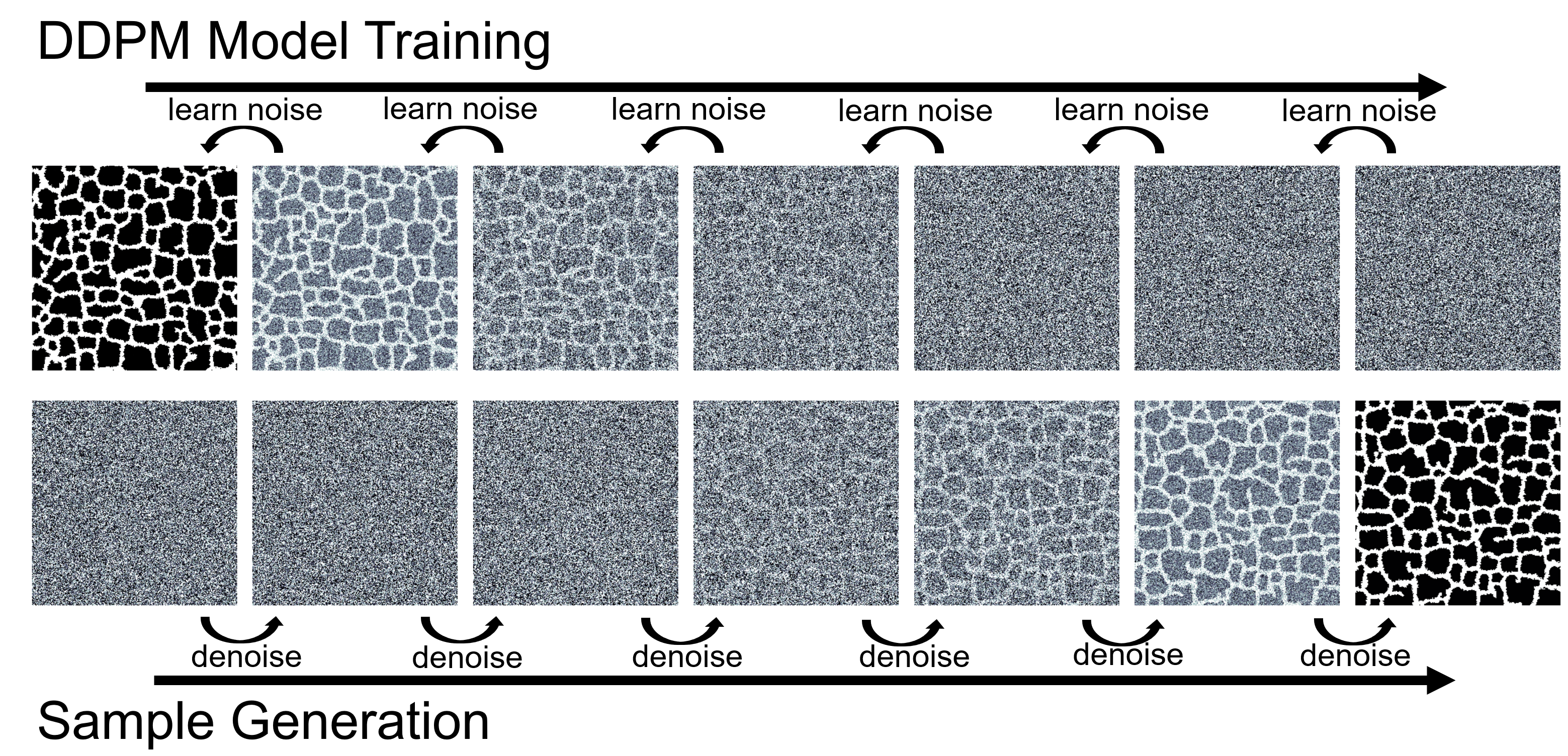

Figure 2: DDPM training learns to predict noise added to cell configurations (top, forward diffusion); generation reverses this process to synthesize new biological patterns from noise (bottom, reverse diffusion). Source: Generative Diffusion Model Surrogates for Agent-Based Biological Models

Figure 2: DDPM training learns to predict noise added to cell configurations (top, forward diffusion); generation reverses this process to synthesize new biological patterns from noise (bottom, reverse diffusion). Source: Generative Diffusion Model Surrogates for Agent-Based Biological Models

Diffusion models work by learning to reverse a gradual noising process. During training, the model learns to predict the noise added to an image at various corruption levels. During generation, it starts from pure noise and iteratively denoises to produce a sample from the learned distribution. The key insight is that "generative modeling methods such as the DDPM have shown promise as model surrogates for other inherently stochastic, complex systems such as the calorimeter shower" in particle physics [1].

Why diffusion over alternatives like GANs? Training stability. "Training GANs poses several practical challenges including mode collapse, training instabilities, and difficulties in capturing long tails of distributions" [3]. Mode collapse, where the generator produces only a subset of the training distribution's diversity, is particularly problematic for surrogate modeling. "Diffusion models offer training stability alongside demonstrable skill in probabilistically generating km-scales" as demonstrated in atmospheric science applications [3].

From Simulation Data to Surrogate Model

The training pipeline starts with generating data from the actual CPM simulations. The researchers used CompuCell3D, one of several mature open-source frameworks for CPM simulation. They generated "5100 images per area of the parameter space and a total of 127500 images for all 25 classes" [1], where each class corresponds to a specific combination of two key parameters.

The DDPM architecture follows the EDM2 framework. "We use the edm2-img64-s preset as defined in the original publication but modify the model inputs to allow for single-channel images" [1]. The single-channel modification reflects the binary nature of CPM outputs: each pixel is either occupied by a cell or empty medium.

Training required substantial computation: "12,748,800 training steps" on "16 V100 GPUs" [1]. This upfront investment pays off when you consider how many surrogate evaluations become possible afterward. The key innovation is class-conditional generation: "by defining different areas of the CPM parameter space to be different classes of images, we exploit this functionality to allow our DDPM to generate images from discrete areas of interest in the parameter space" [1].

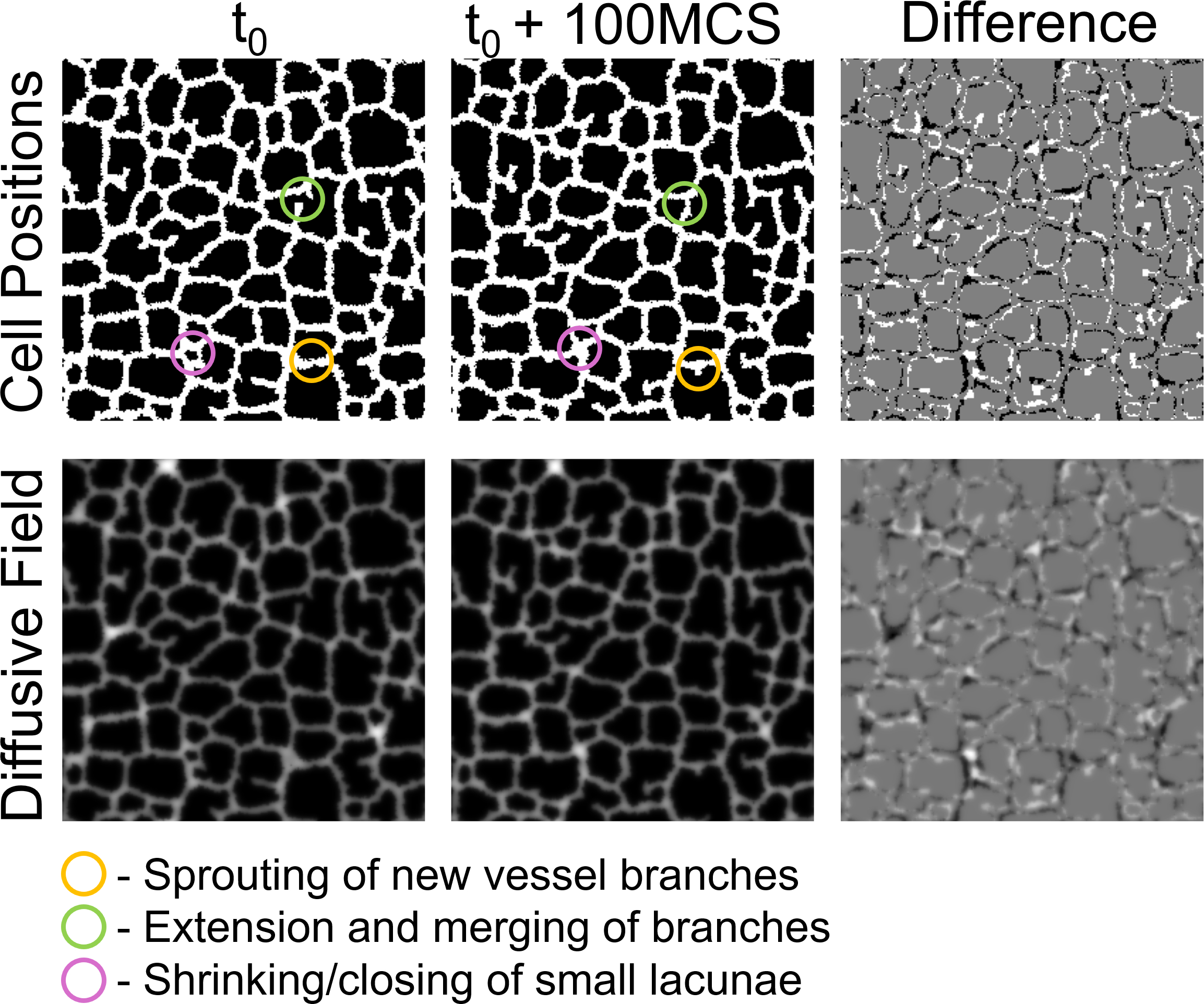

Figure 3: Cellular dynamics during vasculogenesis simulation showing cell positions and the diffusive chemical field. Annotations highlight key biological processes: vessel sprouting (yellow), branch extension and merging (green), and lacunae closure (pink). Source: Deep Learning Surrogates for Cellular Potts Model

Figure 3: Cellular dynamics during vasculogenesis simulation showing cell positions and the diffusive chemical field. Annotations highlight key biological processes: vessel sprouting (yellow), branch extension and merging (green), and lacunae closure (pink). Source: Deep Learning Surrogates for Cellular Potts Model

Validation: Beyond Visual Inspection

How do you verify that generated configurations are "correct" when there's no single correct answer? The stochastic nature of CPMs means ground truth is itself a distribution.

The researchers employed two complementary validation strategies. First, they trained an EfficientNetV2 image classifier to distinguish between the 25 parameter classes. "We used the EfficientNetV2 architecture because it has been designed to train quickly and retain competitive classification performance as compared with much larger models" [1]. The architecture "trains up to 11x faster than previous models while being 6.8x smaller" [4]. This classifier achieved "an accuracy of 95.6% on the separate test dataset" [1] of actual CPM outputs.

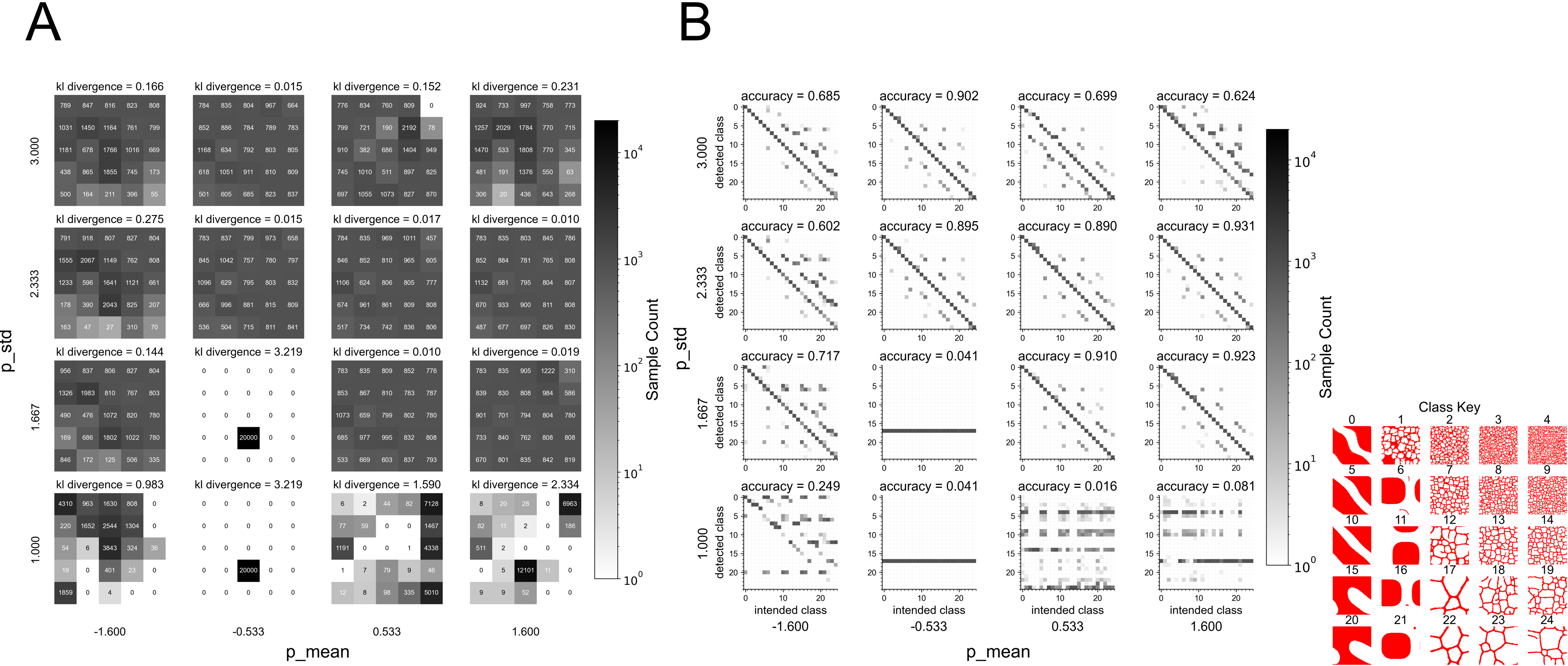

Figure 4: Surrogate quality metrics showing KL divergence between surrogate and ground truth distributions (A) and classifier accuracy for distinguishing parameter classes (B). Low KL divergence indicates the surrogate generates configurations uniformly across intended parameter regions. Source: Generative Diffusion Model Surrogates for Agent-Based Biological Models

Figure 4: Surrogate quality metrics showing KL divergence between surrogate and ground truth distributions (A) and classifier accuracy for distinguishing parameter classes (B). Low KL divergence indicates the surrogate generates configurations uniformly across intended parameter regions. Source: Generative Diffusion Model Surrogates for Agent-Based Biological Models

This validation approach differs notably from standard metrics like Frechet Inception Distance. "We use the Frechet Inception Distance (FID) as a metric for evaluating generative modeling performance but note a scalar value is ill-suited to confirm whether a generated configuration exists within a specific parameter space" [1]. FID tells you if generated images look like training images on average, but "an image classifier can confirm similarity on a per-sample basis, unlike FID which is a global similarity metric" [1].

Second, they performed morphological analysis. Vasculogenesis produces characteristic structures: branching vessel networks with lacunae of varying sizes. "We quantified the vascular morphologic features of branch width and distributions of lacunae area for generated samples using Earth Mover's Distance (EMD)" [1] to compare feature distributions between generated and ground truth configurations.

Figure 5: Visual comparison of ground truth CPM simulations (red) and DDPM surrogate outputs (orange) across the parameter space. The surrogate captures the morphological diversity from dense tissue to sparse vascular networks. Source: Generative Diffusion Model Surrogates for Agent-Based Biological Models

Figure 5: Visual comparison of ground truth CPM simulations (red) and DDPM surrogate outputs (orange) across the parameter space. The surrogate captures the morphological diversity from dense tissue to sparse vascular networks. Source: Generative Diffusion Model Surrogates for Agent-Based Biological Models

The visual comparison in Figure 5 is compelling. Across the parameter space, surrogate-generated configurations exhibit the same qualitative transitions: from dense, confluent tissues at certain parameter values to sparse, network-like structures at others.

The Speedup: 22x Faster Than Traditional Simulation

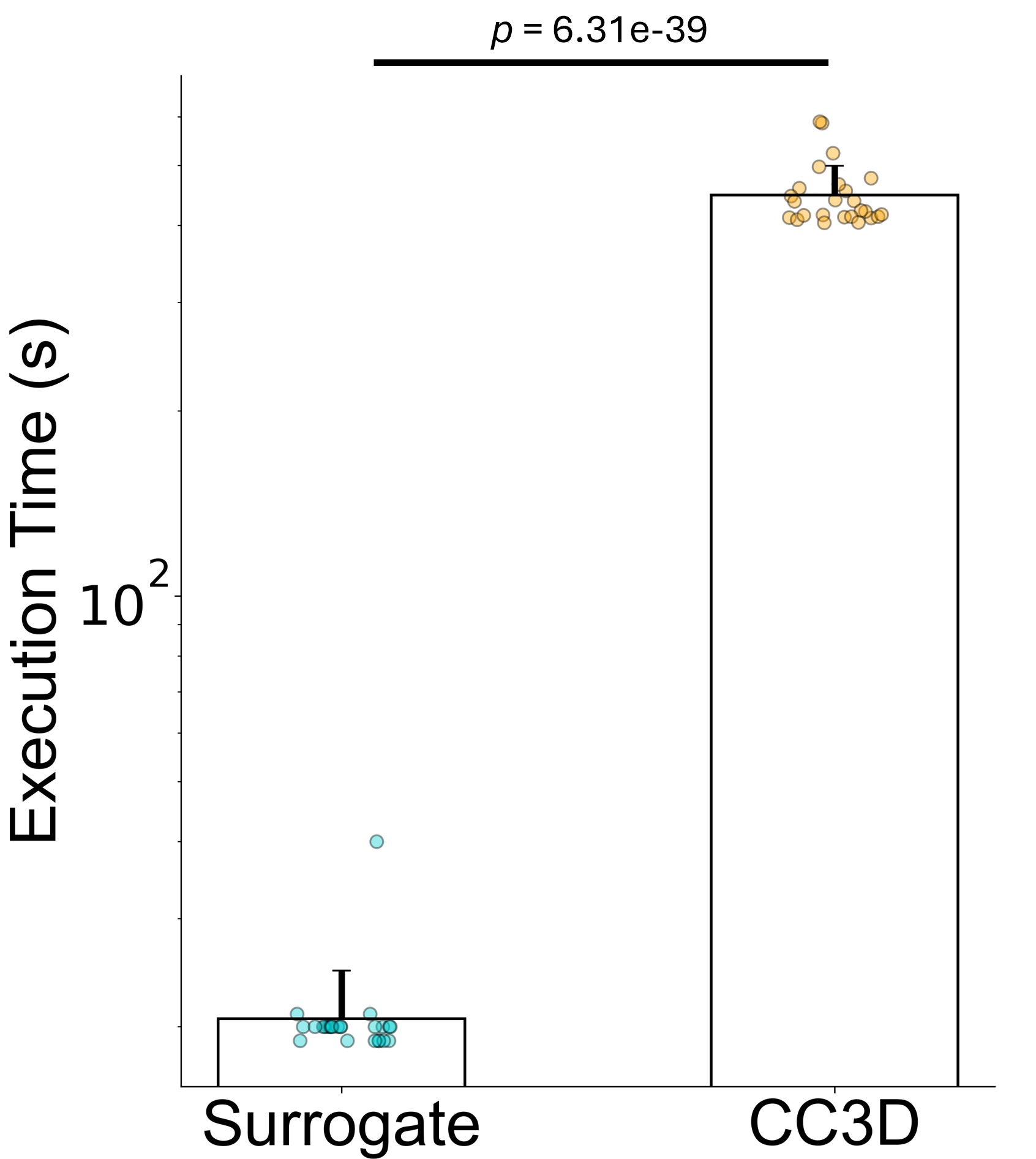

Now for the practical payoff. "Mean DDPM surrogate model evaluations were 20.6s (std 4.0s) as compared with a mean of 447.6s (std 51.1s) for native CompuCell3D code execution" [1]. That's roughly 7.5 minutes per simulation reduced to about 20 seconds per surrogate sample.

Figure 6: Execution time comparison between DDPM surrogate and traditional CC3D simulation, demonstrating approximately 22x speedup. Error bars show standard deviation across evaluation runs. Source: Generative Diffusion Model Surrogates for Agent-Based Biological Models

Figure 6: Execution time comparison between DDPM surrogate and traditional CC3D simulation, demonstrating approximately 22x speedup. Error bars show standard deviation across evaluation runs. Source: Generative Diffusion Model Surrogates for Agent-Based Biological Models

This approximately 22x speedup transforms what's computationally feasible. Consider parameter calibration via Bayesian inference, which might require 10,000 forward model evaluations. At 7.5 minutes each, that's 52 days of continuous computation. At 20 seconds each, it's about 56 hours. Still substantial, but now tractable.

The choice between approaches depends on the application. If you need fast approximate predictions and can tolerate deterministic outputs, the U-Net may be preferable. The U-Net work found that "the surrogate model maintains greater Dice scores than the reference configuration for 10 recursive iterations, predicting up to 1000 MCS ahead" [2]. But if you need to sample from the distribution of possible configurations for a given parameter set, the diffusion model approach is more appropriate.

Where This Breaks Down

The researchers are refreshingly candid about limitations. This is how you know the work is serious science rather than marketing.

Discrete parameter coverage only. The current approach generates configurations at 25 discrete parameter combinations. "By defining different areas of the CPM parameter space to be different classes of images" [1], they discretize what is naturally a continuous space. Generating configurations for intermediate parameter values remains an open challenge.

Endpoint generation, not dynamics. "At long timescales of 20,000 MCS, memory of an initial or reference configuration is lost" [1]. The surrogate generates endpoint configurations without intermediate dynamics. For some applications this is fine. For others, the trajectory matters.

Mode collapse remains a concern. "Mode collapse is the phenomenon when a generative model is unable to demonstrate the diversity of data present in the training set" [1]. While diffusion models are more resistant to this than GANs, the authors observe some parameter regions where the surrogate generates less diverse outputs than the true CPM. They note that "classifier-free guidance has been described that requires the combination of a trained conditional and unconditional diffusion model to control generative sample diversity" [1].

Framework dependence. An interesting observation: "minor differences in algorithmic implementation of models such as the CPM result in drastic numerical differences for equivalent models encoded in different open-source frameworks" [1]. A surrogate trained on CompuCell3D outputs may not generalize to Morpheus or Artistoo despite nominally implementing the same model.

Inverse problems remain open. The surrogate enables fast forward prediction (parameters to configurations), but "for the inverse problem, we may consider adapting image-based parameter estimation methods for mapping computational models to images of their biological counterparts" [1]. Parameter inference from experimental images requires different techniques.

Broader Implications: The Surrogate Modeling Pattern

This work joins a growing body of applications using diffusion models as scientific surrogates. "DDPMs are a key component in CorrDiff, cited as a component in a digital twin for weather forecasting" [1]. The weather application is instructive: "CorrDiff on a single GPU is at least 22 times faster and 1,300 times more energy efficient than the numerical model" [3]. The stochastic nature of atmospheric physics parallels biological simulation: "The stochastic nature of atmospheric physics at km-scale renders downscaling inherently probabilistic" [3].

The pattern appears across scientific computing. According to a taxonomy of ML-simulation integration, "the speedup was 30,000 using surrogates" in some applications [5], and "deep learning is showing striking success and tends to replace other machine learning approaches. We expect these successes to lead to large increases in effective performance (often by several orders of magnitude)" [5].

For biological modeling specifically, a prior study found that "Use of Deep Learning LSTM to produce surrogates of a one-dimensional biological agent simulation. 10^5 simulations took 2 months on a 400 node cluster and were followed by looking at 10^8 surrogate runs" [5]. The efficiency gain from surrogates doesn't just speed up existing workflows; it enables entirely new scales of investigation.

Figure 7: Taxonomy of surrogate modeling approaches in scientific computing. Deterministic methods (U-Net, encoder-decoder) provide single-point predictions with maximum speed. Generative methods (VAEs, GANs, diffusion models) sample from learned distributions, capturing stochasticity. Hybrid approaches combine mechanistic constraints with learned components.

Figure 7: Taxonomy of surrogate modeling approaches in scientific computing. Deterministic methods (U-Net, encoder-decoder) provide single-point predictions with maximum speed. Generative methods (VAEs, GANs, diffusion models) sample from learned distributions, capturing stochasticity. Hybrid approaches combine mechanistic constraints with learned components.

What This Means for Practitioners

If you're working with CPMs or similar agent-based biological models, this research suggests a practical workflow:

For parameter exploration: If your goal is understanding how parameter changes affect emergent phenotypes, a DDPM surrogate can dramatically accelerate the search. The 22x speedup makes interactive exploration practical and enables systematic sweeps that would otherwise be prohibitive.

For generating representative samples: When you need many examples of what configurations look like at given parameters (for training downstream models, generating synthetic data, or statistical analysis), the surrogate provides validated samples at a fraction of the computational cost.

For mechanism investigation: When you need to understand exactly how a specific configuration arose through step-by-step cellular dynamics, the original CPM simulation remains necessary. The surrogate captures what emerges, not how.

For validation: The classifier-based validation approach demonstrated here provides a template for rigorously testing whether generative surrogates capture the relevant structure of the target domain.

# DDPM Surrogate Usage Example

# Based on Comlekoglu et al. (2025), arXiv:2505.09630

import torch

import time

# Parameter classes map to specific CPM configurations

# Each class = (cell-medium adhesion J_cm, decay constant lambda_d)

PARAMETER_CLASSES = {

12: {"J_cm": -6, "lambda_d": 0.06, "phenotype": "vascular_dense"},

14: {"J_cm": -6, "lambda_d": 0.10, "phenotype": "vascular_sparse"},

# ... 25 classes total covering the parameter space

}

def generate_surrogate_samples(model, class_label, num_samples=10, device="cuda"):

"""Generate CPM configurations using the DDPM surrogate.

Args:

model: Pre-trained class-conditional DDPM

class_label: Parameter class (0-24) to generate

num_samples: Number of configurations to generate

device: Computation device

Returns:

Binary cell masks of shape (num_samples, 1, 256, 256)

"""

model.eval()

# Create class conditioning tensor

class_cond = torch.full((num_samples,), class_label, device=device)

# Start from pure noise

x = torch.randn(num_samples, 1, 256, 256, device=device)

# DDIM sampling (50 steps for ~20s generation)

with torch.no_grad():

for t in reversed(range(0, 1000, 20)): # 50 steps

t_batch = torch.full((num_samples,), t, device=device)

noise_pred = model(x, t_batch, class_cond)

x = ddim_step(x, noise_pred, t) # Update sample

# Convert to binary cell mask (threshold at 0)

cell_mask = (x > 0).float()

return cell_mask

# Timing comparison

start = time.time()

samples = generate_surrogate_samples(model, class_label=12, num_samples=10)

surrogate_time = time.time() - start

print(f"Surrogate: {surrogate_time:.1f}s for 10 samples")

print(f"CC3D equivalent: ~4476s (10 x 447.6s)")

print(f"Speedup: ~{4476/surrogate_time:.0f}x")

# Output: Surrogate: ~206s, Speedup: ~22x

Future Directions

The authors outline several promising extensions. "Aligned diffusion schrodinger bridges allows for learning the stochastic dynamics in between samples such that conditional generation given an arbitrary reference may occur" [1]. This could enable trajectory modeling rather than just endpoint generation.

Another direction involves the inverse problem: "for the inverse problem, we may consider adapting image-based parameter estimation methods for mapping computational models to images of their biological counterparts" [1]. This would enable going from experimental images to inferred model parameters.

The ultimate vision connects to digital twins: surrogate models as components in closed-loop systems that continuously update predictions based on real experimental data. Weather forecasting is already moving in this direction, and biological applications seem likely to follow.

Conclusion

The application of diffusion models as surrogates for stochastic biological simulations represents a practical step toward accelerating computational biology workflows. The 22x speedup is meaningful for parameter exploration. The distributional nature of diffusion models matches the stochastic nature of biological simulation. And the validation approach using image classifiers provides a rigorous check that surrogates generate appropriate configurations.

This is not a replacement for mechanistic simulation. The surrogate depends entirely on the original model for training data, and it cannot extrapolate beyond the parameter space it has seen. But for exploration within that space, it offers a path to rapid iteration that was previously unavailable.

For computational biologists, the question shifts from "can we afford to explore this parameter space?" to "how do we want to validate that our surrogate faithfully represents the original model?" That is a better problem to have.

References

[1] Comlekoglu, T., Toledo-Marin, J.Q., DeSimone, D.W., Peirce, S.M., Fox, G., & Glazier, J.A. (2025). Generative Diffusion Model Surrogates for Mechanistic Agent-Based Biological Models. arXiv:2505.09630. https://arxiv.org/abs/2505.09630

[2] Comlekoglu, T., et al. (2025). Surrogate Modeling of Cellular-Potts Agent-Based Models as a Segmentation Task Using U-Net. PLOS Computational Biology. https://journals.plos.org/ploscompbiol/article?id=10.1371/journal.pcbi.1013626

[3] Mardani, M., et al. (2024). Residual Corrective Diffusion Modeling for km-Scale Atmospheric Downscaling (CorrDiff). arXiv:2309.15214. https://arxiv.org/abs/2309.15214

[4] Tan, M. & Le, Q.V. (2021). EfficientNetV2: Smaller Models and Faster Training. ICML 2021. arXiv:2104.00298.

[5] Fox, G. & Jha, S. (2019). Learning Everywhere: A Taxonomy for the Integration of Machine Learning and Simulations. IEEE eScience 2019. arXiv:1909.13340.

[6] Karras, T., et al. (2024). Analyzing and Improving the Training Dynamics of Diffusion Models (EDM2). ICLR 2024. arXiv:2312.02696.

[7] Ho, J., Jain, A., & Abbeel, P. (2020). Denoising Diffusion Probabilistic Models. NeurIPS 2020. arXiv:2006.11239.

[8] Wortel, I.M.N. & Textor, J. (2021). Artistoo: A Library to Build, Share, and Explore Simulations of Cells and Tissues in the Web Browser. eLife, 10:e61288.