The Historical Accident That Split Drug Design in Two (And the Contrastive Model That Reunites It)

Discovering a new drug takes more than a decade and costs around $2.6 billion 1. A significant chunk of that time goes to computational screening: searching for molecules that bind disease-relevant proteins.

Over the past thirty years, two completely separate disciplines have emerged to tackle this search. Structure-based drug design (SBDD) works from the 3D shape of a target protein. Ligand-based drug design (LBDD) works from examples of molecules known to be active. These approaches use different data, different algorithms, and different assumptions. They rarely inform each other.

The strange part: they are solving the same core problem. Both try to predict which small molecules will bind a protein target. This separation is not principled. It is a historical accident, born from the fact that structural biology and medicinal chemistry evolved as distinct fields. A new model called ConGLUDe shows we can fix it, and the fix works better than either approach alone 2.

Why Two Approaches to the Same Problem?

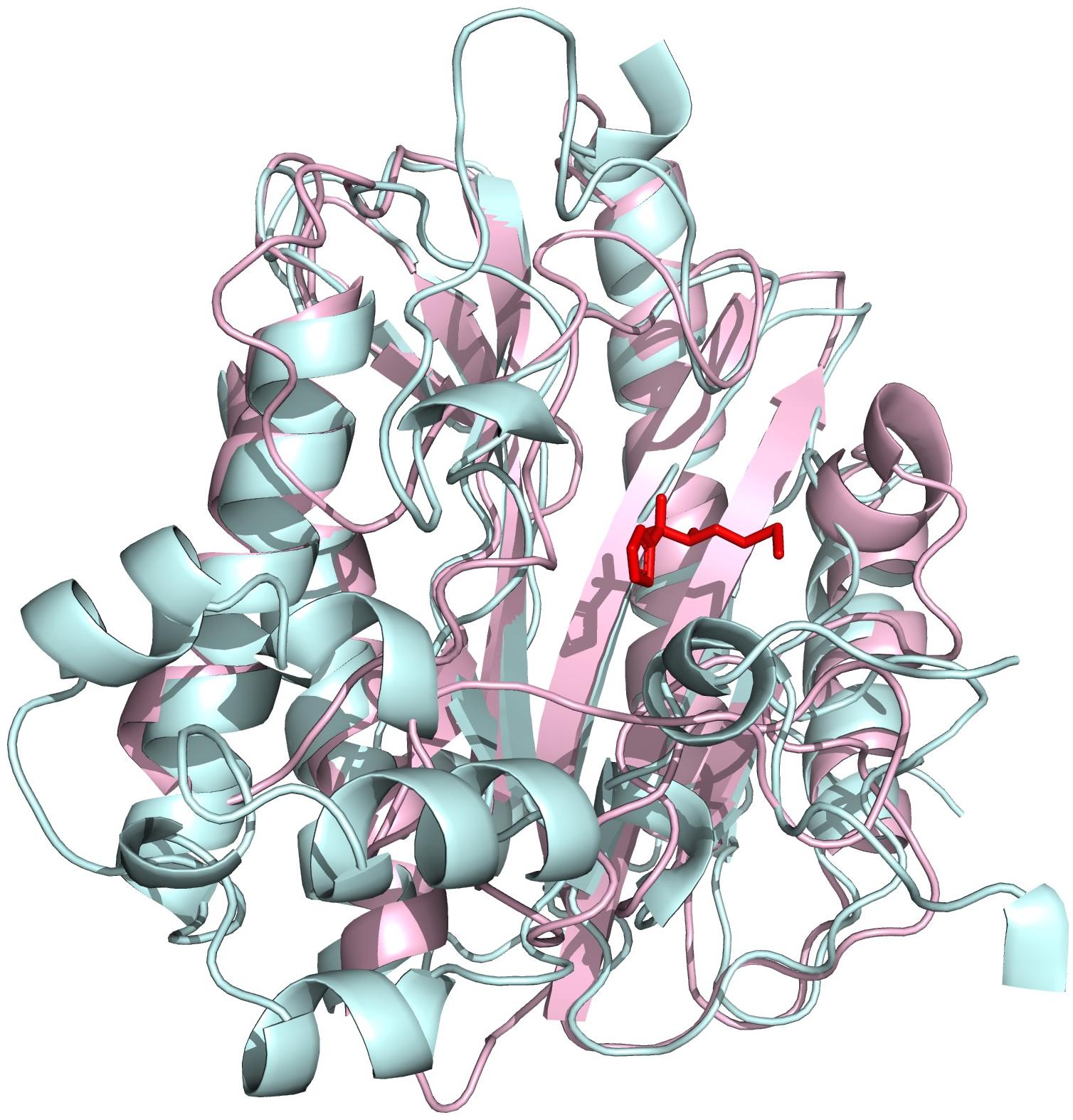

Structure-based drug design became possible once we could determine protein 3D structures at atomic resolution. The Protein Data Bank now contains roughly 245,000 entries 2, giving researchers a rich catalog of target shapes. If you know the geometry of a binding pocket, you can computationally screen molecules that might fit, much like testing which key fits a lock. The approach is powerful when structural data is available. When it is not, you are stuck.

Ligand-based drug design took the opposite path. Rather than starting with the target's shape, it starts with molecules already known to interact with similar targets. PubChem alone contains approximately 300 million bioactivity measurements 2, providing massive datasets of what has worked before. By learning patterns from known active compounds, LBDD can suggest new candidates. But it struggles to extrapolate far beyond its training examples.

Figure 1: A protein structure with a bound ligand, illustrating the binding pocket that SBDD methods try to characterize computationally. Source: Corso et al., DockGen

Figure 1: A protein structure with a bound ligand, illustrating the binding pocket that SBDD methods try to characterize computationally. Source: Corso et al., DockGen

These two approaches have complementary blind spots. SBDD can find novel scaffolds but needs good structural data. LBDD can work with partial structural knowledge but is limited by the chemical diversity of known actives. As the ConGLUDe authors observe, "structure-based and ligand-based computational drug design have traditionally relied on disjoint data sources and modeling assumptions, limiting their joint use at scale" 2.

The question becomes: what if a single model could learn from both binding geometries and ligand bioactivity data simultaneously?

The CLIP Intuition, Applied to Proteins and Ligands

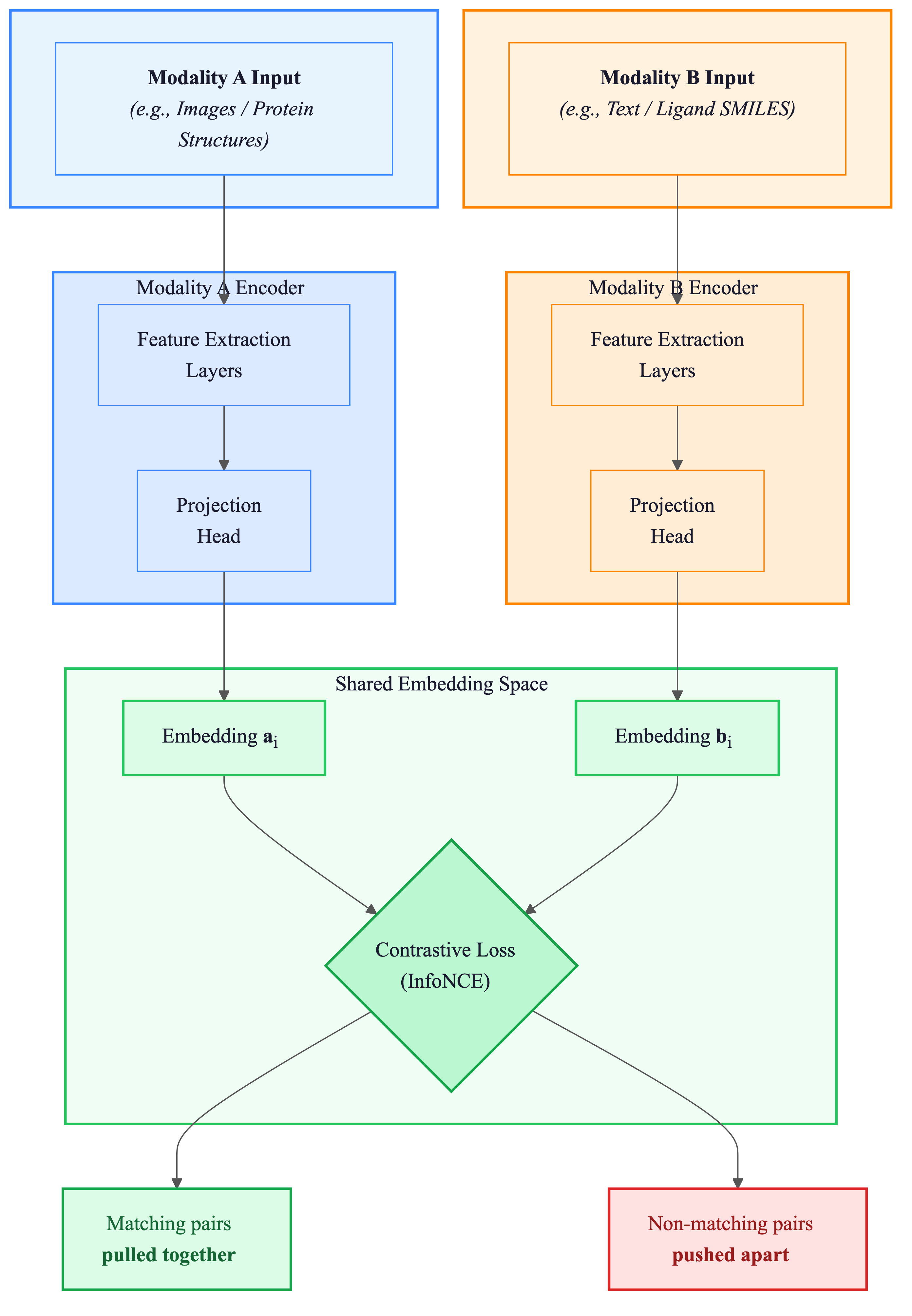

The key insight comes from an unexpected place: computer vision. In 2021, OpenAI showed with CLIP that learning to match images with text descriptions creates representations that transfer remarkably well to new tasks, matching ResNet-50 on ImageNet zero-shot without using any of the 1.28 million labeled training examples ResNet was trained on 3. The core idea is contrastive learning: train two encoders so that matching pairs end up close together in a shared embedding space while non-matching pairs end up far apart.

ConGLUDe applies the same logic to proteins and ligands. Instead of images and captions, you have protein structures and small molecules. Instead of asking "which caption describes this image?", you ask "which molecules bind this protein?"

Figure 2: The CLIP architecture that inspired ConGLUDe. Contrastive pre-training aligns two different modalities in a shared space, enabling cross-modal retrieval. Source: Radford et al., CLIP

Figure 2: The CLIP architecture that inspired ConGLUDe. Contrastive pre-training aligns two different modalities in a shared space, enabling cross-modal retrieval. Source: Radford et al., CLIP

This reframing matters practically. Instead of asking "how tightly does this molecule bind?" (a regression problem), contrastive models ask "which molecules belong with which proteins?" (a retrieval problem). DrugCLIP showed this was powerful: it could screen the Enamine library of 6 billion molecules in approximately 30 hours 4. For context, screening 10 billion compounds with commercial docking methods would take 3,000 years and cost over $800,000 4. But DrugCLIP still required a pre-defined binding pocket as input. ConGLUDe removes that constraint.

How ConGLUDe Actually Works

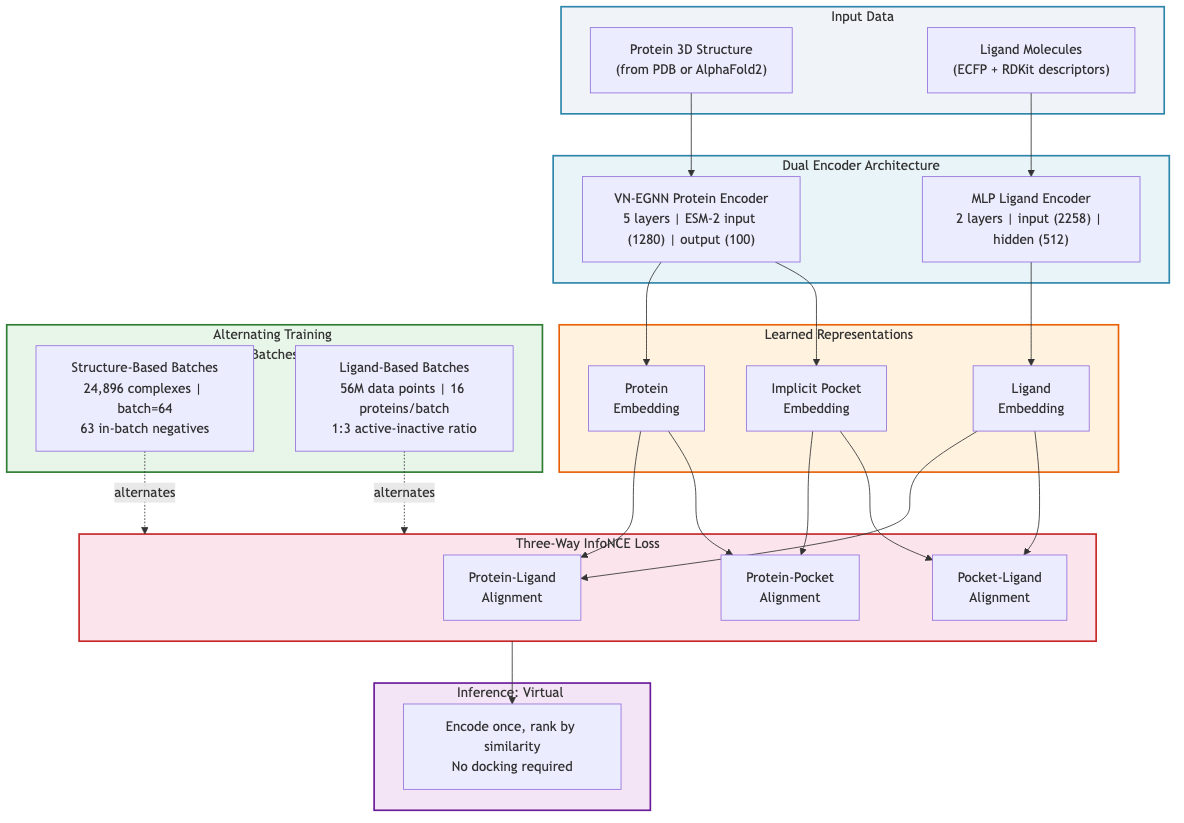

ConGLUDe's architecture couples two encoders aligned through a shared embedding space.

The protein encoder uses a 5-layer VN-EGNN (Vector Neuron Equivariant Graph Neural Network) with input dimensions of 1280 from ESM-2 protein language model embeddings and an output dimension of 100 2. This geometric encoder "produces whole-protein representations and implicit embeddings of predicted binding sites" 2. Critically, it does not require a pre-defined binding pocket. The model learns to identify binding sites on its own.

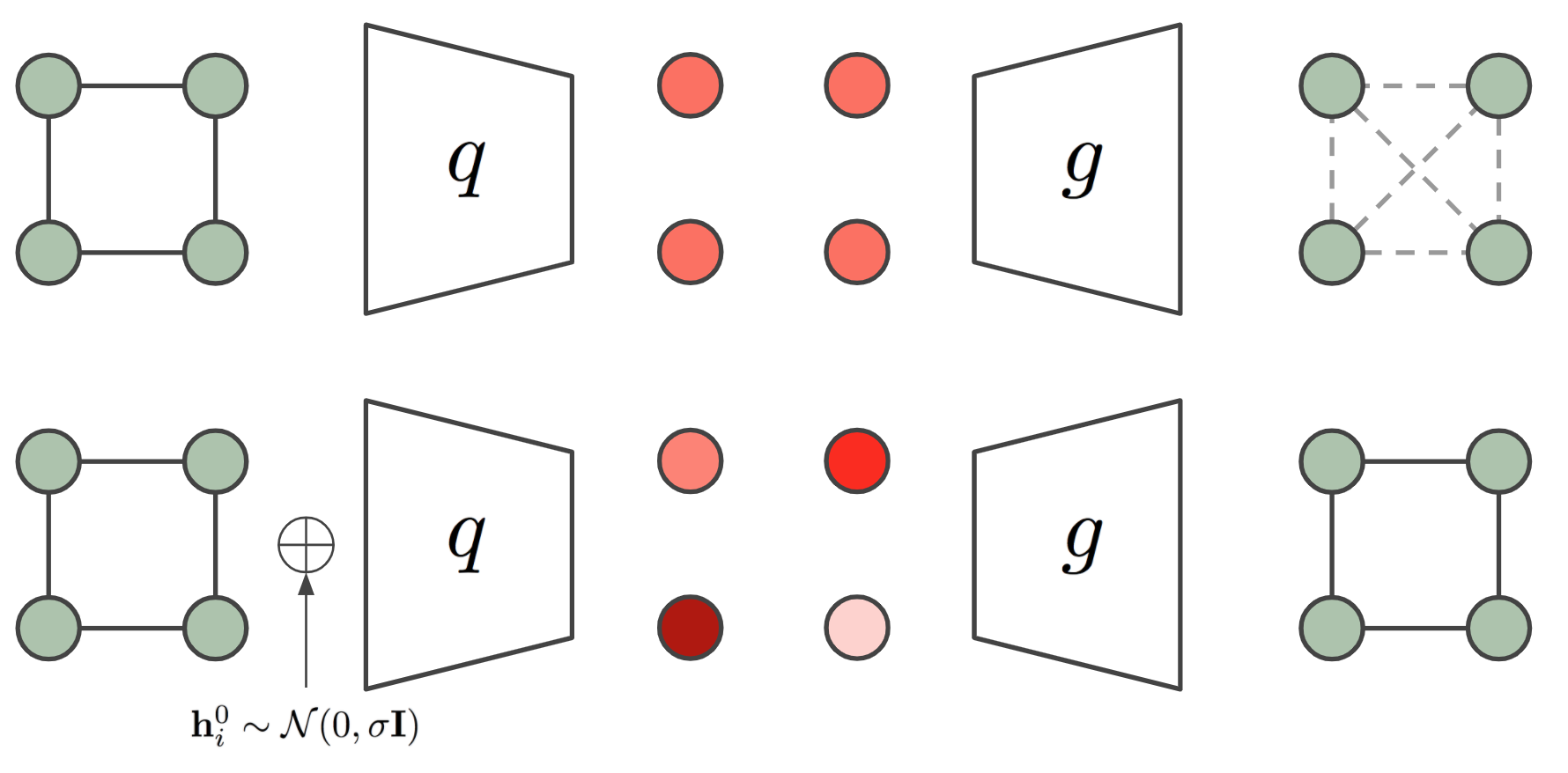

Why equivariant architectures? Because molecular geometry matters. The antidepressant Citalopram provides a clear example: it "has two enantiomers but only the S-enantiomer has the desired therapeutic effect. The difference between the S- and R-form of the molecule, however, is only detectable by a reflection-sensitive GNN" 5. Standard GNNs that ignore spatial relationships miss these distinctions.

Figure 3: EGNN architecture. Top: standard GNN where node features are identical regardless of geometry. Bottom: EGNN with coordinate updates preserving geometric equivariance. ConGLUDe's protein encoder builds on this principle. Source: Satorras et al. 6

Figure 3: EGNN architecture. Top: standard GNN where node features are identical regardless of geometry. Bottom: EGNN with coordinate updates preserving geometric equivariance. ConGLUDe's protein encoder builds on this principle. Source: Satorras et al. 6

The ligand encoder is deliberately simple. Ligands are represented as extended connectivity fingerprints (radius 2, length 2048) concatenated with 210 RDKit chemical descriptors, yielding an input dimension of 2258, processed through a two-layer MLP with hidden dimension 512 2. Why not something more complex? Because "molecular fingerprints combined with MLPs often outperform more complex architectures such as GNNs for encoding small molecules" 2. When your protein encoder already handles geometric complexity, a fast and effective ligand encoder is more valuable than a fancy one.

The training procedure is where unification happens concretely. ConGLUDe "integrates structure- and ligand-based learning by alternating between (i) structure-based batches, where it learns to detect and characterize binding sites and pair them with their ligands, and (ii) ligand-based batches, where it leverages large-scale bioactivity measurements" 2. Structure-based training uses a batch size of 64, creating 63 negative ligands per protein through in-batch negative sampling. Ligand-based batches contain 16 proteins, with actives and inactives sampled at a 1:3 ratio 2.

Figure 4: ConGLUDe's dual-encoder architecture with alternating training batches. The VN-EGNN protein encoder and MLP ligand encoder produce embeddings aligned through a three-way InfoNCE contrastive loss. Source: Schneckenreiter et al., ConGLUDe

Figure 4: ConGLUDe's dual-encoder architecture with alternating training batches. The VN-EGNN protein encoder and MLP ligand encoder produce embeddings aligned through a three-way InfoNCE contrastive loss. Source: Schneckenreiter et al., ConGLUDe

The alignment uses "a three-way InfoNCE loss, similar to CLIP, aligning protein, pocket, and ligand embeddings along complementary axes" 2. This extension to three axes is the key novelty: it introduces a ligand-conditioned pocket prediction task 2. The model does not just learn which ligands bind which proteins. It also learns where on the protein they bind, conditioned on the specific ligand.

Once training is complete, screening becomes computationally cheap. "Virtual screening reduces to efficient similarity evaluations between protein and ligand representations, enabling scalable large-scale screening without explicit docking" 2. You encode the protein. You encode the ligand candidates. You compute similarity scores. No expensive docking simulations required.

No Pocket Required: A Bigger Deal Than It Sounds

Most structure-based screening methods need you to specify where on the protein the drug should bind. That sounds reasonable until you consider real-world cases: novel targets with no known ligands, proteins with multiple potential binding sites, and allosteric sites that conventional approaches miss entirely.

ConGLUDe sidesteps this by producing whole-protein representations where binding site prediction becomes implicit. During training, the model "defines a binding site for a given ligand as the geometric center of all protein residues that lie within a 4 Angstrom radius of any ligand atom" 2, but at inference time, it does not need you to specify this. The model figures out where to look.

The benchmark results make this concrete. On the realistic LIT-PCBA benchmark, "natively pocket-agnostic approaches significantly outperform pocket-requiring methods, even when the correct pocket is provided as input to the latter" 2. Read that again: giving pocket-aware methods the correct pocket still does not help them beat ConGLUDe's pocket-free approach on this dataset. The pocket-agnostic representation captures information that explicit pocket definitions miss.

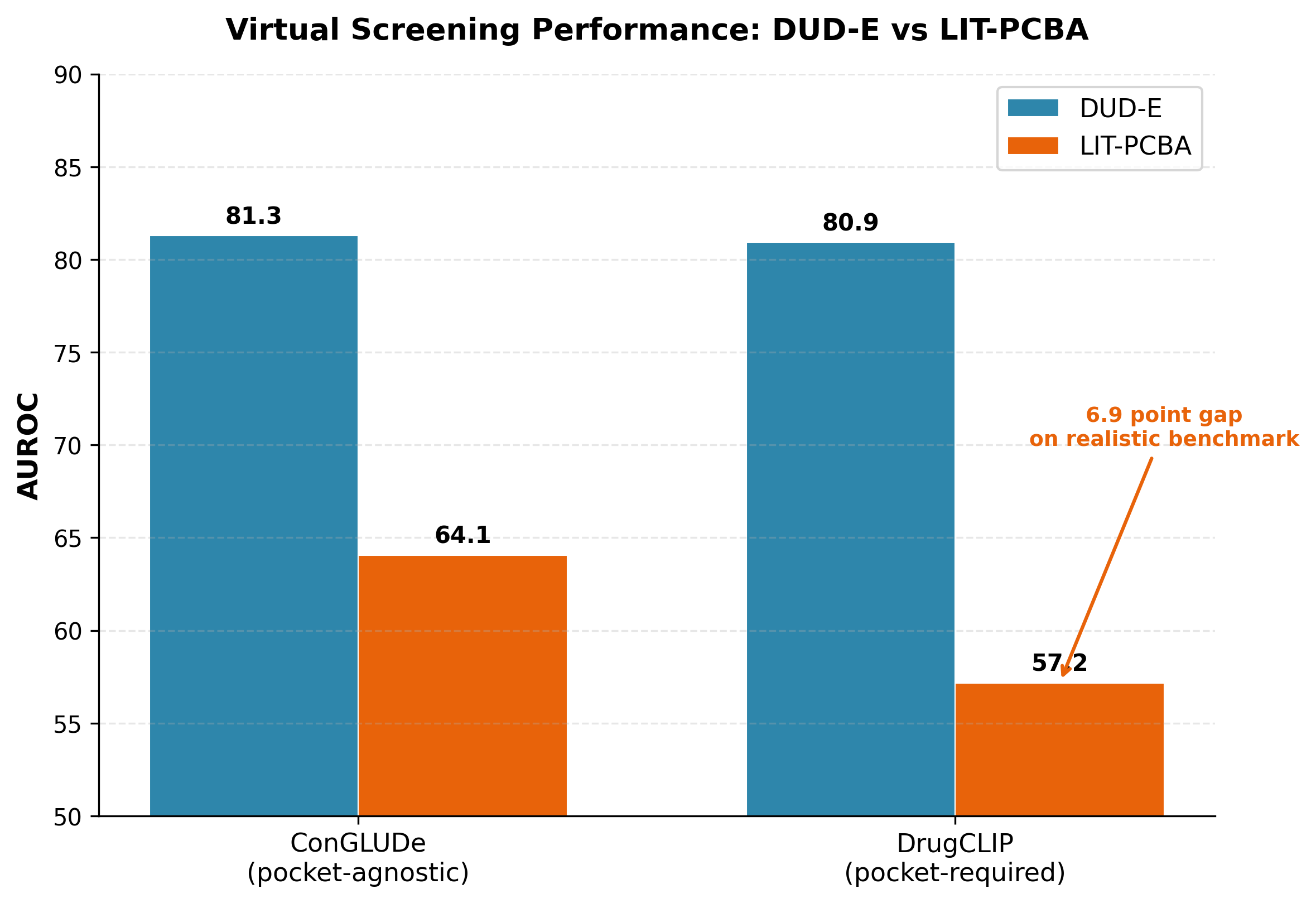

The Numbers: Two Benchmarks, Two Different Realities

ConGLUDe was evaluated on two standard virtual screening benchmarks that test different things.

DUD-E contains 22,886 active compounds against 102 protein targets 4. Its decoys are generated computationally, which means models can sometimes learn shortcuts based on physicochemical property distributions rather than genuine binding signals. LIT-PCBA takes a different approach: 15 targets with experimentally confirmed actives and inactives from real high-throughput screening 2. The active-to-inactive ratio is far more realistic, with "the proportion of actives significantly smaller than 0.1%" 4. Any method that generalizes across both benchmarks is doing something fundamentally different from methods that excel on only one.

ConGLUDe achieved an AUROC (area under the receiver operating characteristic curve) of 81.29 on DUD-E and 64.06 on LIT-PCBA in pocket-agnostic virtual screening 2. For comparison, DrugCLIP, a strong contrastive baseline that requires binding pocket definitions, achieved 80.93 on DUD-E and 57.17 on LIT-PCBA 4. The DUD-E numbers look close, but the LIT-PCBA gap is telling. On the harder, more realistic benchmark, ConGLUDe's advantage widens substantially. And "ConGLUDe is the only model that demonstrates strong cross-benchmark generalization" 2.

Figure 5: Virtual screening performance on DUD-E and LIT-PCBA. ConGLUDe (pocket-agnostic) matches DrugCLIP (pocket-required) on DUD-E and substantially outperforms on the more realistic LIT-PCBA benchmark. Data from 2 and 4.

Figure 5: Virtual screening performance on DUD-E and LIT-PCBA. ConGLUDe (pocket-agnostic) matches DrugCLIP (pocket-required) on DUD-E and substantially outperforms on the more realistic LIT-PCBA benchmark. Data from 2 and 4.

The statistical evidence is strong: "the difference in per-ligand AUCs between ConGLUDe and DiffDock is highly significant (Wilcoxon test, p ~ 10⁻²⁴)" 2. And DiffDock evaluation "requires multiple GPU-days, making it impractical for large-scale virtual screening" 2.

Both Streams Matter

Ablation studies confirm that the unification is empirically necessary, not just philosophically satisfying. "On LIT-PCBA, ablating each component leads to a deterioration of the performance metrics, which indicates that all components together contribute to the effectiveness of ConGLUDe" 2. Remove the structure-based signal, performance drops. Remove the ligand-based signal, performance drops. The unification is not decoration; it is load-bearing.

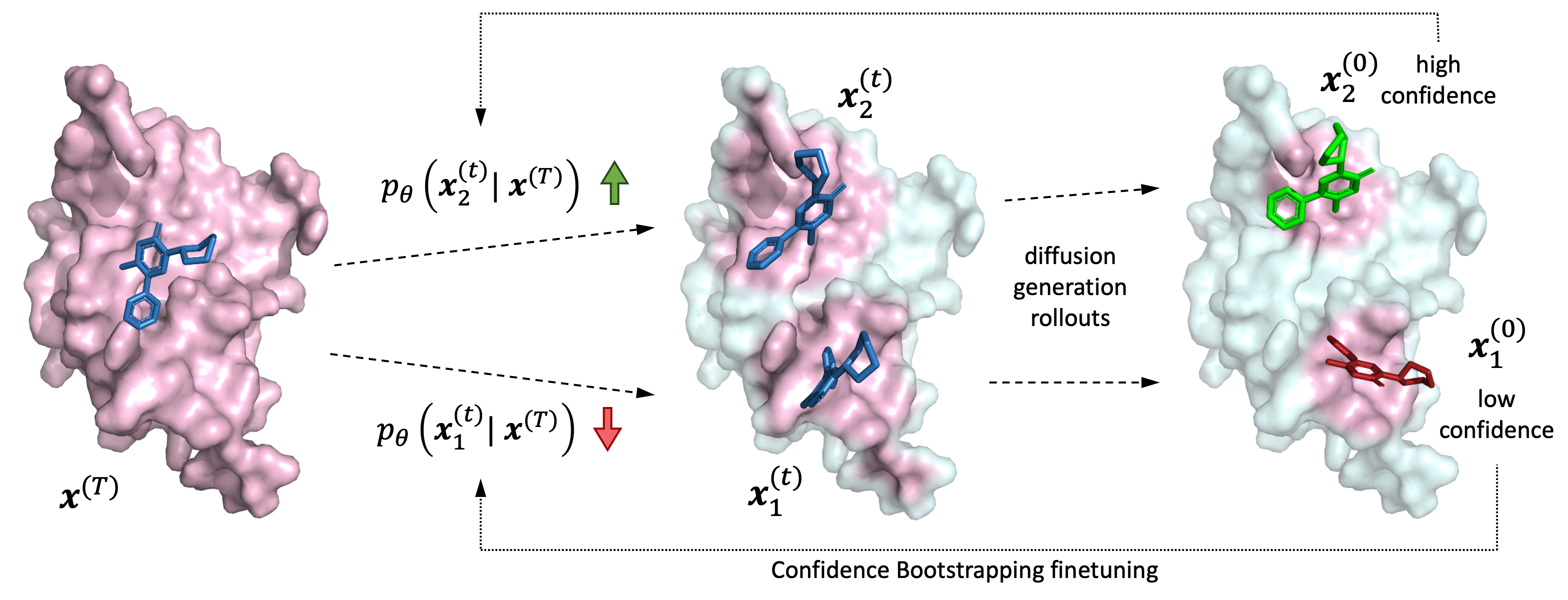

Beyond Virtual Screening

ConGLUDe is not limited to screening. It also performs target fishing (given a molecule, predict which proteins it binds), achieving an AUROC of 65.6 2. It handles ligand-conditioned pocket prediction, identifying where on a protein a specific ligand is likely to bind, with DCC success rates of 0.602 on COACH420, 0.525 on HOLO4K, and 0.689 on PDBBind2020 2. ConGLUDe "outperforms all baselines on PDBbind ligand-conditioned pocket selection" 2 and "identifies ligand-specific pockets substantially faster than traditional docking or co-folding approaches" 2.

Figure 6: Diffusion-based molecular docking generates candidate binding poses, then scores their confidence. ConGLUDe sidesteps explicit pose generation entirely, using embedding similarity for faster screening. Source: Corso et al., DockGen

Figure 6: Diffusion-based molecular docking generates candidate binding poses, then scores their confidence. ConGLUDe sidesteps explicit pose generation entirely, using embedding similarity for faster screening. Source: Corso et al., DockGen

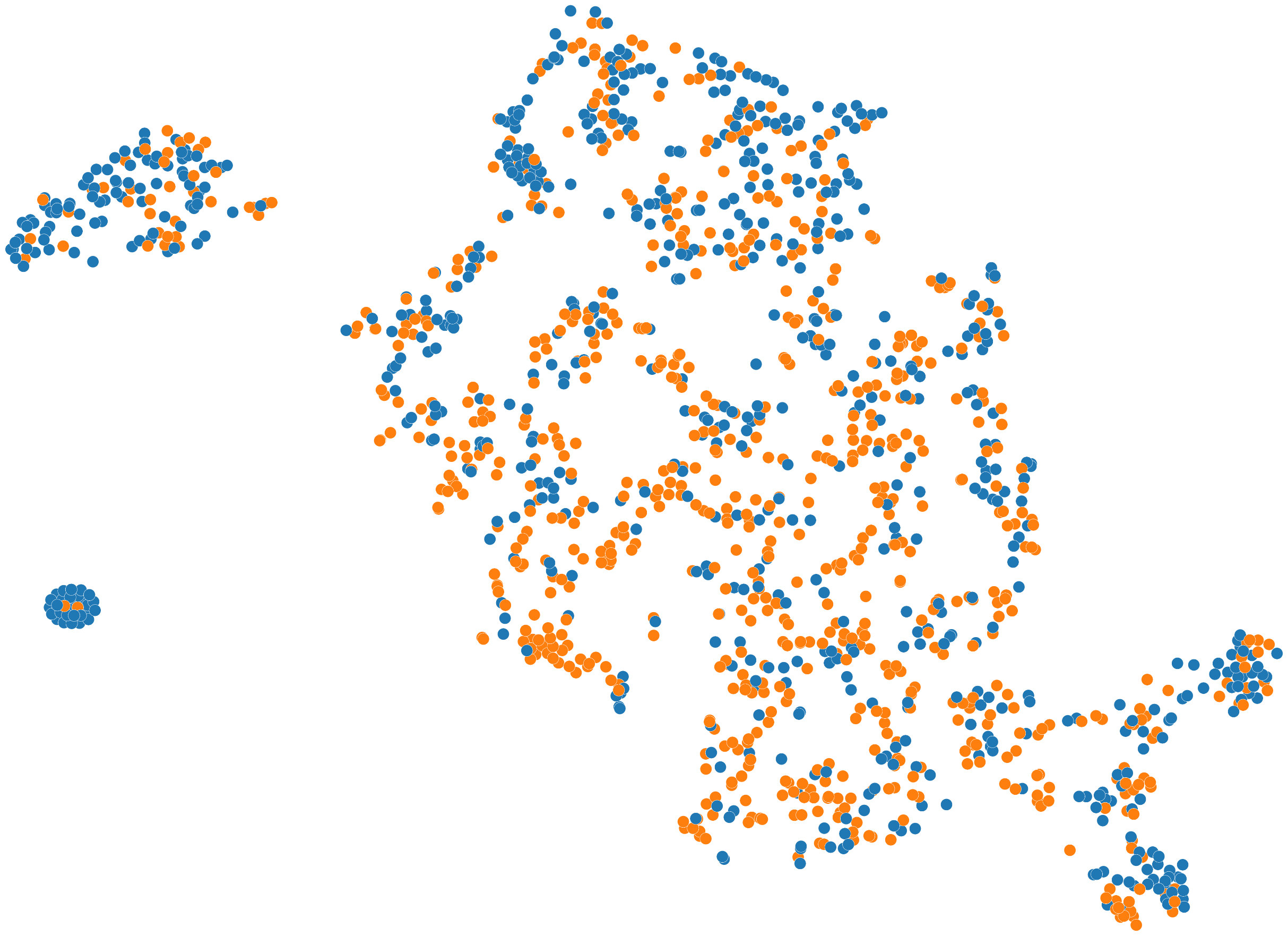

Figure 7: Molecular embedding space from contrastive pre-training. Molecules with similar binding properties cluster together, demonstrating how contrastive learning captures meaningful chemical relationships. ConGLUDe builds a similar space that aligns both protein and ligand representations. Source: Wang et al., MolCLR

Figure 7: Molecular embedding space from contrastive pre-training. Molecules with similar binding properties cluster together, demonstrating how contrastive learning captures meaningful chemical relationships. ConGLUDe builds a similar space that aligns both protein and ligand representations. Source: Wang et al., MolCLR

Where This Does Not Work

ConGLUDe has real limitations worth stating directly.

It requires both structural data and ligand activity data during training. If you have a novel target with no known structure and no known binders, the model cannot help. The training was conducted on NVIDIA A100 GPUs with 40GB memory for 200-350 epochs 2, using 24,896 structure-based complexes and 3,526 proteins with 56,187,278 ligand-based data points 2. This is a substantial data and compute requirement.

Performance drops for all methods when encountering allosteric pockets that are rarely seen during training. "Unconditioned predictors frequently miss these sites" 2. While ConGLUDe's ligand-conditioned approach helps here, allosteric binding remains a frontier challenge.

The broader generalization problem persists. Recent work found that "existing machine learning-based docking models have very weak generalization abilities" when tested on unseen protein classes 7. While ConGLUDe generalizes better than most, truly novel target families remain difficult for all methods.

And the practical reality: these are computational predictions. Drug discovery still takes more than a decade and costs billions. No contrastive model changes that fundamental reality on its own. Better virtual screening helps, but it does not shortcut the wet-lab validation pipeline.

What Other Fragmented Fields Are Waiting?

ConGLUDe demonstrates something beyond its specific results: when you find two separately developed tools solving overlapping problems, the default should be to try unifying them. The contrastive learning framework is particularly well-suited for this because it recasts the problem as information retrieval. You encode things into a shared space and let similarity do the rest.

This pattern is already spreading. ProtCLIP achieved improvements of 75% on average across five cross-modal transformation benchmarks 8 by aligning protein and biotext representations through function-informed multi-modal pre-training. MolCLR showed that contrastive pre-training on approximately 10 million unlabeled molecules "significantly improves the performance of GNNs on various molecular property benchmarks" 9. Contrastive alignment between complementary modalities keeps working, across domains.

The question ConGLUDe raises extends beyond drug discovery. Protein function prediction has separate communities working from sequence, structure, and interaction data. Genomics has separate approaches for variant effect prediction and gene expression modeling. Drug-target affinity prediction is treated as a distinct field from binding pose prediction, despite both characterizing the same physical interaction 1.

How many other computational biology problems remain artificially separated, not because the problems are fundamentally different, but because the communities and datasets developed independently? If the answer is many, then contrastive learning across modalities may be one of the most productive directions the field can pursue. The real question is whether this scales beyond pairwise unification: can a single model integrate structural data, ligand activity, genomic context, and clinical outcomes into one representation space?

Footnotes

-

Hu, W., et al. (2023). Deep Learning Methods for Small Molecule Drug Discovery: A Survey. IEEE Transactions on Artificial Intelligence. ↩ ↩2

-

Schneckenreiter, L., Luukkonen, S., Friedrich, L., Kuhn, D., & Klambauer, G. (2026). Contrastive Geometric Learning Unlocks Unified Structure- and Ligand-Based Drug Design. arXiv:2601.09693. https://arxiv.org/abs/2601.09693 ↩ ↩2 ↩3 ↩4 ↩5 ↩6 ↩7 ↩8 ↩9 ↩10 ↩11 ↩12 ↩13 ↩14 ↩15 ↩16 ↩17 ↩18 ↩19 ↩20 ↩21 ↩22 ↩23 ↩24 ↩25 ↩26 ↩27 ↩28 ↩29

-

Radford, A., et al. (2021). Learning Transferable Visual Models From Natural Language Supervision. arXiv:2103.00020. https://arxiv.org/abs/2103.00020 ↩

-

Gao, B., et al. (2023). DrugCLIP: Contrastive Protein-Molecule Representation Learning for Virtual Screening. arXiv:2310.06367. https://arxiv.org/abs/2310.06367 ↩ ↩2 ↩3 ↩4 ↩5 ↩6

-

Schneuing, A., et al. (2022). Structure-Based Drug Design with Equivariant Diffusion Models. arXiv:2210.13695. https://arxiv.org/abs/2210.13695 ↩

-

Satorras, V. G., Hoogeboom, E., & Welling, M. (2021). E(n) Equivariant Graph Neural Networks. arXiv:2102.09844. https://arxiv.org/abs/2102.09844 ↩

-

Corso, G., et al. (2024). Deep Confident Steps to New Pockets: Strategies for Docking Generalization. ICLR 2024. ↩

-

Zhou, H., Yin, M., Wu, W., Li, M., Fu, K., Chen, J., Wu, J., & Wang, Z. (2024). ProtCLIP: Function-Informed Protein Multi-Modal Learning. arXiv:2412.20014. https://arxiv.org/abs/2412.20014 ↩

-

Wang, Y., et al. (2022). Molecular Contrastive Learning of Representations via Graph Neural Networks. Nature Machine Intelligence. https://arxiv.org/abs/2102.10056 ↩