Code World Models: Teaching LLMs to Simulate Execution

In 2018, a red car learned to dream.

It sounds fanciful, but that car, rendered in a simple 2D racing environment, became the protagonist of one of the most influential papers in modern AI. David Ha and Jurgen Schmidhuber demonstrated that an agent could learn to race by building an internal model of its world, then training entirely within its own imagination. The agent did not just memorize track patterns; it learned to simulate what would happen next.

Seven years later, that same insight is reshaping how AI understands code. When GPT-4 first demonstrated the ability to write functional code from natural language descriptions, many engineers assumed the hard part was over. But anyone who has tried to use LLMs for real software engineering work knows the uncomfortable truth: these models excel at generating syntactically correct code while often failing to understand what that code actually does. They pattern-match against billions of lines of training data without ever executing a single instruction.

Meta's Code World Model (CWM), released in September 2025, applies the dreaming car's lesson to software engineering. By training on observation-action trajectories from Python interpreters and Docker environments, CWM learns not just what code looks like, but what happens when it runs. The results speak for themselves: 65.8% on SWE-bench Verified and 68.6% on LiveCodeBench.

This post explores how code world models work, why they matter for agentic software engineering, and what they mean for engineers building AI-assisted development tools.

Figure 1: The world models concept from Ha and Schmidhuber's 2018 paper. Just as humans maintain mental models to plan actions, AI agents can learn compressed representations of their environment. For code, this means simulating execution internally before committing to changes. (Source: Ha & Schmidhuber, "World Models," 2018)

Figure 1: The world models concept from Ha and Schmidhuber's 2018 paper. Just as humans maintain mental models to plan actions, AI agents can learn compressed representations of their environment. For code, this means simulating execution internally before committing to changes. (Source: Ha & Schmidhuber, "World Models," 2018)

The Execution Understanding Gap

Traditional code LLMs are trained on one objective: predict the next token in a sequence of source code. This approach produces models that understand syntax, naming conventions, and common coding patterns remarkably well. But it creates a blind spot around program semantics.

Consider a concrete example. A syntax-focused model knows that sorted() is commonly followed by a list variable. An execution-aware model understands something deeper: that calling sorted() on a list produces a new sorted list without modifying the original, while list.sort() modifies the list in place and returns None. The first is a statistical pattern; the second is execution semantics.

# A syntax-matching model might not understand the difference here

original = [3, 1, 4, 1, 5]

# sorted() returns a new list, leaving original unchanged

new_list = sorted(original)

print(original) # [3, 1, 4, 1, 5] - unchanged

print(new_list) # [1, 1, 3, 4, 5]

# list.sort() modifies in place and returns None

result = original.sort()

print(result) # None - not the sorted list!

print(original) # [1, 1, 3, 4, 5] - modified in place

This distinction matters because real software engineering depends on execution semantics. Debugging requires tracing what code actually does, not what it looks like. Refactoring demands understanding how changes propagate through program state. Fixing a GitHub issue in a real codebase means predicting how edits interact with thousands of lines of surrounding code.

Research on execution trace prediction validates this gap. Training models to predict "the intermediate traces of the function as a scratchpad of intermediate computations generally yields more accurate output predictions" compared to models that predict final outputs directly [6]. The act of simulating execution step by step forces the model to learn actual program semantics rather than statistical shortcuts.

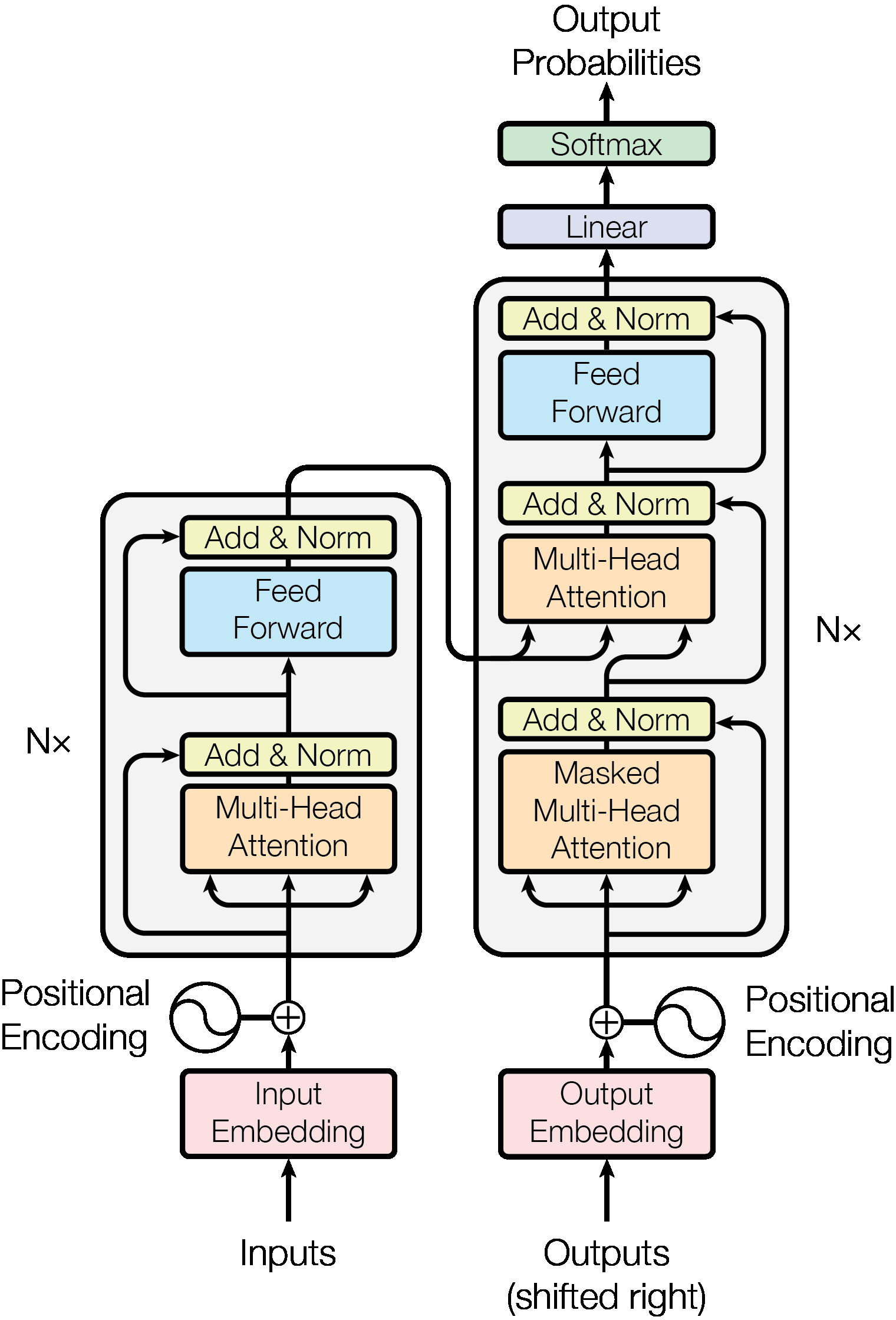

Figure 2: The Transformer architecture underlying modern code models. While powerful for sequence prediction, standard transformers learn from static text alone, missing execution dynamics. (Source: Vaswani et al., "Attention Is All You Need," 2017)

Figure 2: The Transformer architecture underlying modern code models. While powerful for sequence prediction, standard transformers learn from static text alone, missing execution dynamics. (Source: Vaswani et al., "Attention Is All You Need," 2017)

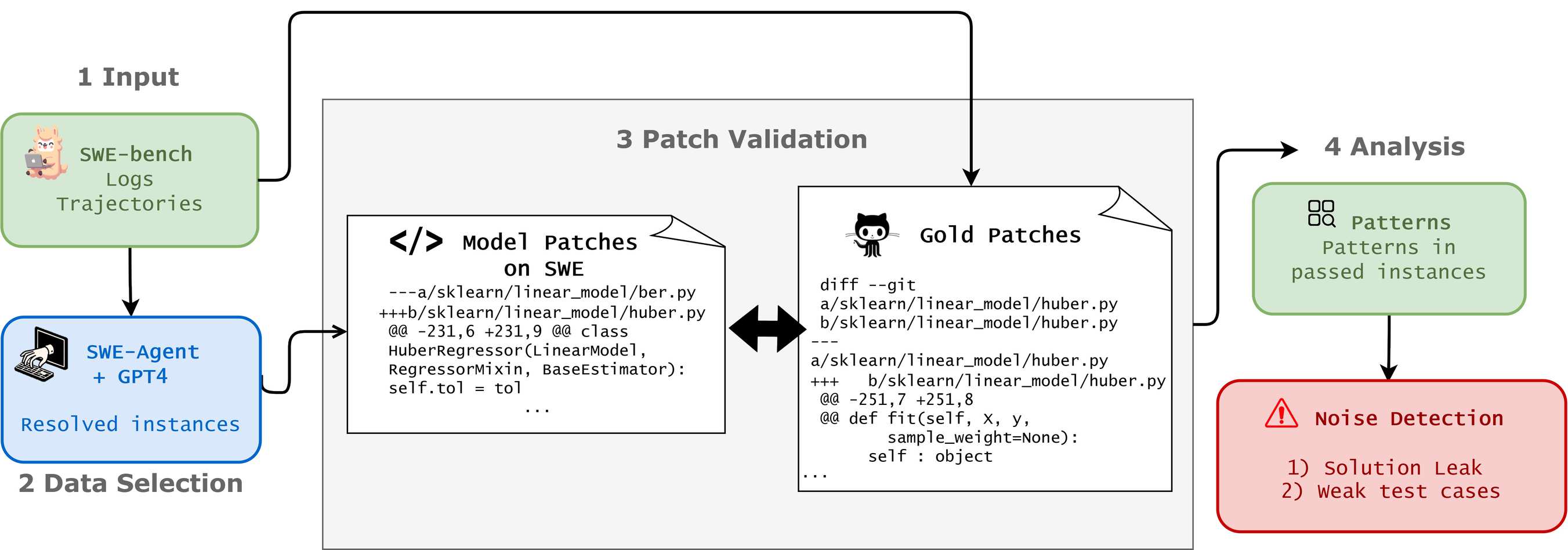

The practical consequence appears starkly in software engineering benchmarks. SWE-bench, which tests models on real GitHub issues, reveals that even sophisticated models struggle with genuine code understanding. Analysis found that "32.67% of the successful patches involve 'cheating' as the solutions were directly provided in the issue report or the comments." When filtering for problems requiring real understanding, "the resolution rate of SWE-Agent+GPT-4 drops from 12.47% to 3.97%."

This matters because agentic coding scenarios depend precisely on the capability that static training neglects: understanding what code does when it runs.

How Code World Models Work

The world models concept originates from Ha and Schmidhuber's 2018 paper, which proposed that agents could "learn compact representations of their environment and train policies entirely within their own generative dreams." The agent builds an internal model of how the world works, then uses that model to plan actions without constantly querying the real environment.

Figure 3: The original world models architecture: a VAE compresses observations into latent space (Z), enabling the agent to simulate and predict future states. Code world models apply this principle to program execution. (Source: Ha & Schmidhuber, 2018)

Figure 3: The original world models architecture: a VAE compresses observations into latent space (Z), enabling the agent to simulate and predict future states. Code world models apply this principle to program execution. (Source: Ha & Schmidhuber, 2018)

Applied to code, this means training models not just on source code text but on observation-action trajectories from actual execution. Meta's CWM paper describes training on trajectories from "Python interpreter and agentic Docker environments," where the model observes the state of variables after each executed line and learns to predict how that state evolves.

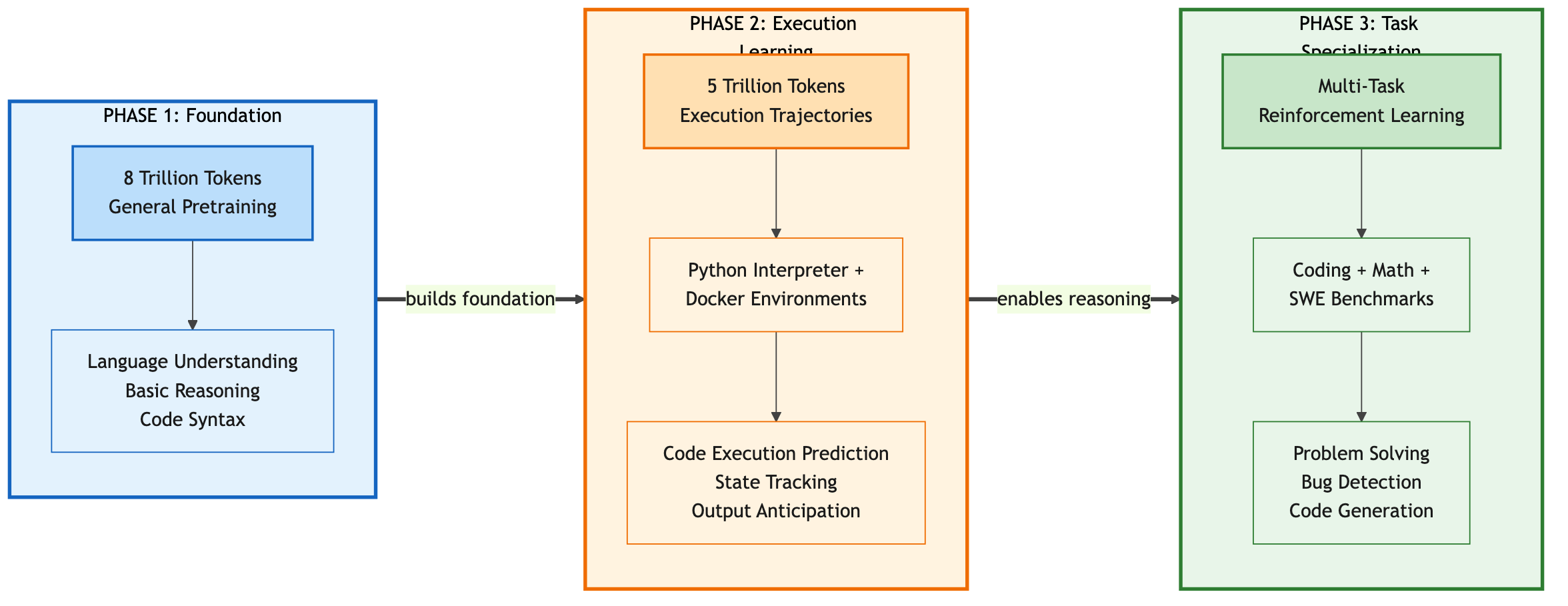

The Three-Phase Training Pipeline

CWM is a 32-billion parameter dense, decoder-only transformer with a 131,000 token context window. But the architecture alone does not explain its capabilities. What makes CWM distinctive is how it was trained.

Phase 1: General Pretraining (8T Tokens)

Standard LLM pretraining on approximately 8 trillion tokens of text and code. This establishes the foundation: language understanding, basic code syntax, and the broad knowledge base that enables reasoning about diverse programming concepts.

Phase 2: Mid-Training on Execution Trajectories (5T Tokens)

This is where CWM diverges from standard code models. The mid-training phase uses approximately 5 trillion tokens of observation-action trajectories from two sources:

Python Interpreter Traces: For each code snippet, the training data includes the sequence of variable states after each line executes. The model sees not just x = y + z but the actual values of x, y, and z at that moment.

Docker Agent Interactions: CWM also trains on trajectories from agentic interactions in Docker environments. The model observes how file systems change, how shell commands affect state, and how multi-step coding tasks unfold.

Phase 3: Multi-Task Reinforcement Learning

Reinforcement learning across coding, mathematics, and software engineering tasks refines the model's ability to apply its execution understanding to solve problems. Unlike supervised training that learns from correct examples, RL training rewards the model for actually solving problems.

Figure 4: CWM's three-phase training pipeline. Phase 1 establishes foundational language and code understanding with 8 trillion tokens. Phase 2 adds execution awareness through 5 trillion tokens of Python interpreter and Docker traces. Phase 3 refines capabilities through multi-task RL on coding, math, and SWE benchmarks. (Source: Meta FAIR, "CWM," 2025)

Figure 4: CWM's three-phase training pipeline. Phase 1 establishes foundational language and code understanding with 8 trillion tokens. Phase 2 adds execution awareness through 5 trillion tokens of Python interpreter and Docker traces. Phase 3 refines capabilities through multi-task RL on coding, math, and SWE benchmarks. (Source: Meta FAIR, "CWM," 2025)

What the Model Actually Learns

The mid-training phase teaches CWM to function as what the research team calls a "neural debugger." Consider this example of execution trace prediction:

# The model learns to predict state changes at each step

def calculate_discount(price, rate):

# State after line: {price: 100.0, rate: 0.15}

discount = price * rate

# State after line: {price: 100.0, rate: 0.15, discount: 15.0}

final_price = price - discount

# State after line: {price: 100.0, rate: 0.15, discount: 15.0, final_price: 85.0}

return final_price

Rather than learning that discount = price * rate typically has a variable name on the left and arithmetic on the right, the model learns that after this line executes with price=100.0 and rate=0.15, the state includes discount=15.0. This is execution simulation, not pattern matching.

The key insight is that "code is precise, fast, reliable and interpretable" as a representation of world dynamics [7]. Unlike visual environments where world models must approximate continuous physics, code world models can learn exact execution semantics.

SWE-agent and Agentic Applications

Code world models become particularly powerful when integrated with agentic frameworks designed for software engineering. SWE-agent, introduced in 2024, demonstrates how Agent-Computer Interfaces (ACIs) tailored for LLMs can substantially improve performance on coding tasks.

Figure 5: The SWE-bench Plus evaluation pipeline, which filters for genuine solutions versus patches that exploit weak test cases or include answers from issue descriptions. Real code understanding requires more than pattern matching. (Source: SWE-bench Plus, 2024)

Figure 5: The SWE-bench Plus evaluation pipeline, which filters for genuine solutions versus patches that exploit weak test cases or include answers from issue descriptions. Real code understanding requires more than pattern matching. (Source: SWE-bench Plus, 2024)

The SWE-agent framework introduces specialized commands for code interaction: search, view line ranges, edit, execute tests. The observation is that "SWE-agent's custom agent-computer interface (ACI) significantly enhances an agent's ability to create and edit code files, thereby streamlining the software development process."

Standard code LLMs plugged into SWE-agent achieve reasonable results through iteration: generate a patch, run tests, observe failures, try again. But this approach treats execution feedback as an external oracle. The model generates code, waits for the environment to tell it what happened, then adjusts.

Code world models shift this dynamic. A model that can internally simulate execution can:

Pre-evaluate patches before committing: Rather than generating code and hoping it works, the model can simulate expected behavior and catch obvious failures before they reach the test harness.

Plan multi-step fixes: Complex bugs often require coordinated changes across multiple files. Internal execution simulation helps the model reason about how changes propagate through the codebase.

Learn from fewer environmental interactions: In agentic frameworks, each external action takes time and computational resources. A model that can simulate internally needs fewer external validations.

The benchmark results support this advantage. CWM achieves "65.8% on SWE-bench Verified with test-time scaling and 68.6% on LiveCodeBench," substantially above models trained only on static code.

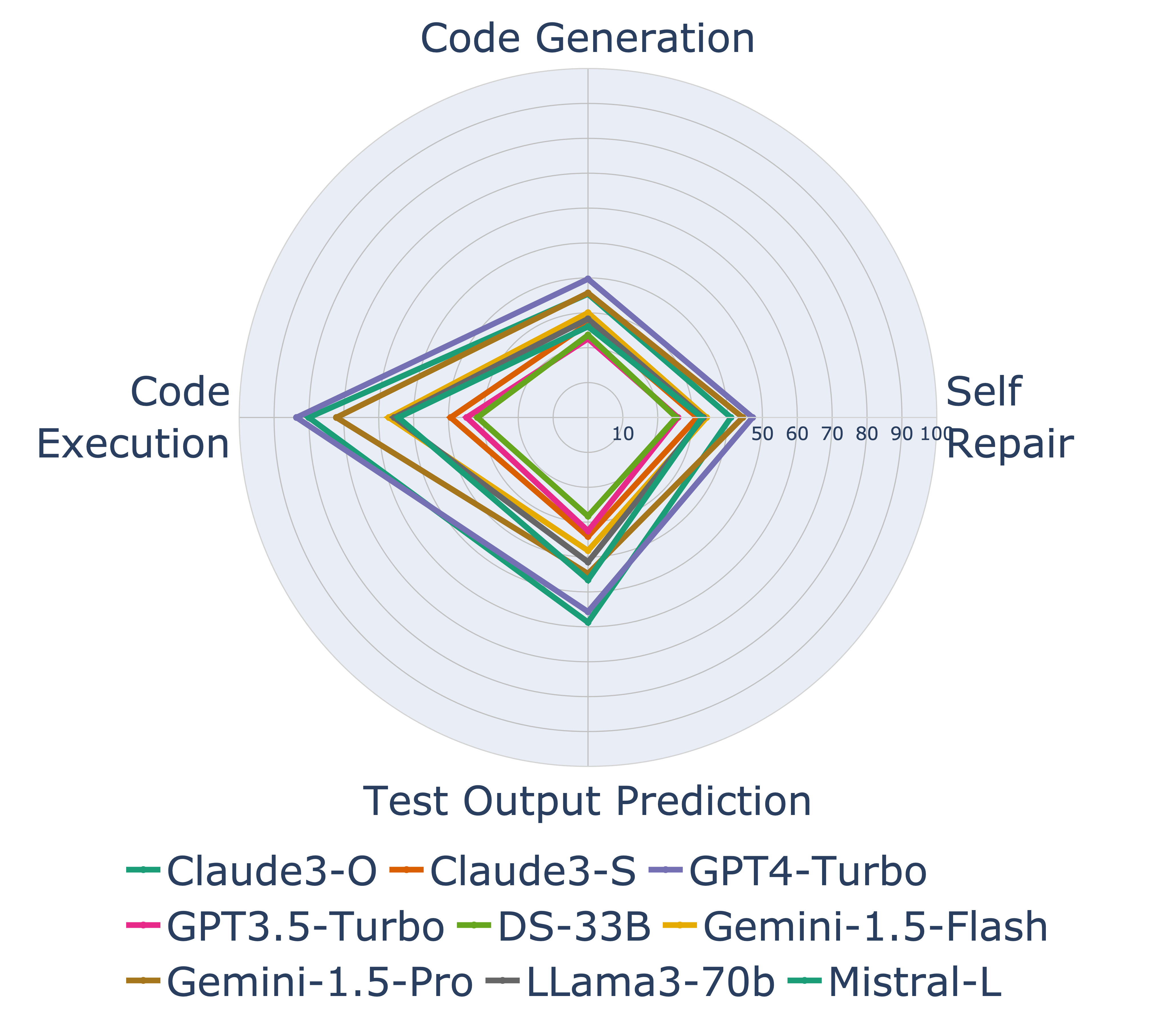

Figure 6: LiveCodeBench radar chart comparing major LLMs across four code capabilities. The code execution axis directly evaluates world model capability, measuring whether models can predict what code does without running it. (Source: LiveCodeBench, 2024)

Figure 6: LiveCodeBench radar chart comparing major LLMs across four code capabilities. The code execution axis directly evaluates world model capability, measuring whether models can predict what code does without running it. (Source: LiveCodeBench, 2024)

The Benchmark Reality Check

Impressive benchmark numbers require context. CWM's 65.8% on SWE-bench Verified should be interpreted carefully.

SWE-bench Verified "contains 500 verified issues with clear issue descriptions and strong test cases," making it a more rigorous test than the full benchmark. But even this curated subset has limitations. Analysis found substantial performance gaps between cleaned benchmarks and real-world conditions: "resolution rate dropped to 0.55% on SWE-Bench+ dataset," a version collected after model training cutoffs to prevent data contamination.

The researchers also noted that "over 94% of the issues were created before LLM's knowledge cutoff dates, posing potential data leakage issues." When evaluating any code model, this temporal contamination risk deserves consideration.

LiveCodeBench provides complementary evaluation by "continuously collecting new problems over time from contests across three competition platforms." This contamination-free approach gives more confidence in generalization claims. The benchmark evaluates four scenarios: code generation, self-repair, code execution prediction, and test output prediction. The code execution scenario directly tests world model capability: can the model predict what code does without running it?

The 68.6% LiveCodeBench result suggests CWM's execution understanding transfers beyond the specific training distribution. But competitive programming problems remain simpler than production codebases. Real software engineering involves massive context, implicit requirements, complex dependencies, and ambiguous specifications. No benchmark fully captures this complexity.

Alternative Approaches: Code as World Model

Interestingly, "code world model" can mean something quite different in other research contexts. Rather than training neural networks to simulate execution, some researchers generate explicit code that models environment dynamics.

This approach, described as "a novel approach to generate RL world models by writing Python code with an LLM," uses language models to produce interpretable, executable models of environments. The results are remarkable: "model-based RL agents with exceptional sample efficiency and inference speed (from four to six orders of magnitude faster compared to directly querying an LLM as a world model)."

The insight is that code offers precision and speed that neural network predictions cannot match. When you need to plan thousands of steps ahead, running generated Python code is vastly more efficient than querying a neural network repeatedly.

These two meanings of "code world model" represent complementary approaches. Neural networks that simulate code excel at understanding and debugging existing programs. Code that simulates worlds excels at efficient planning in codified domains.

Building Agentic Systems with Code World Models

For engineers building AI-assisted development tools, code world models suggest several architectural patterns.

Execution-Aware Retrieval

Before the model generates code, it must find relevant context. Standard retrieval uses embedding similarity to locate related code snippets. Execution-aware retrieval can augment this with behavioral matching: find code that produces similar outputs for given inputs, or code that manipulates similar data structures.

This matters for bug fixing, where the relevant code may be semantically distant (different file, different function) but behaviorally connected (writes to the same database field, modifies the same state).

Speculative Execution for Patch Validation

Rather than generating one solution and testing it, generate multiple candidates and use internal execution simulation to filter before external validation:

# Pseudocode for speculative patch validation

def validate_patch_candidates(model, issue, codebase, candidates):

"""

Use world model predictions to filter patches before running tests.

"""

viable_patches = []

for patch in candidates:

# Simulate execution on test inputs

predicted_states = model.simulate_execution(

code=apply_patch(codebase, patch),

test_inputs=issue.test_inputs

)

# Check if predicted states match expected behavior

if matches_expected(predicted_states, issue.expected_behavior):

viable_patches.append(patch)

# Only run expensive external tests on filtered candidates

return run_actual_tests(viable_patches)

This reduces the number of expensive test executions while improving solution quality. The GIF-MCTS approach demonstrates this pattern, achieving "model-based RL agents with exceptional sample efficiency and inference speed."

Hierarchical Planning with Execution Checkpoints

Complex tasks benefit from decomposition. The code world model simulates high-level plans, then refines each component. At each level, execution simulation validates that the plan achieves intended behavior before committing to implementation.

Research on meta-task planning shows that breaking tasks into sub-tasks with explicit dependencies enables smaller models to compete with larger ones: "LLaMA-3.1-8B equipped with PMC under one demonstration example surpasses GPT-4 by a large margin" on complex planning tasks.

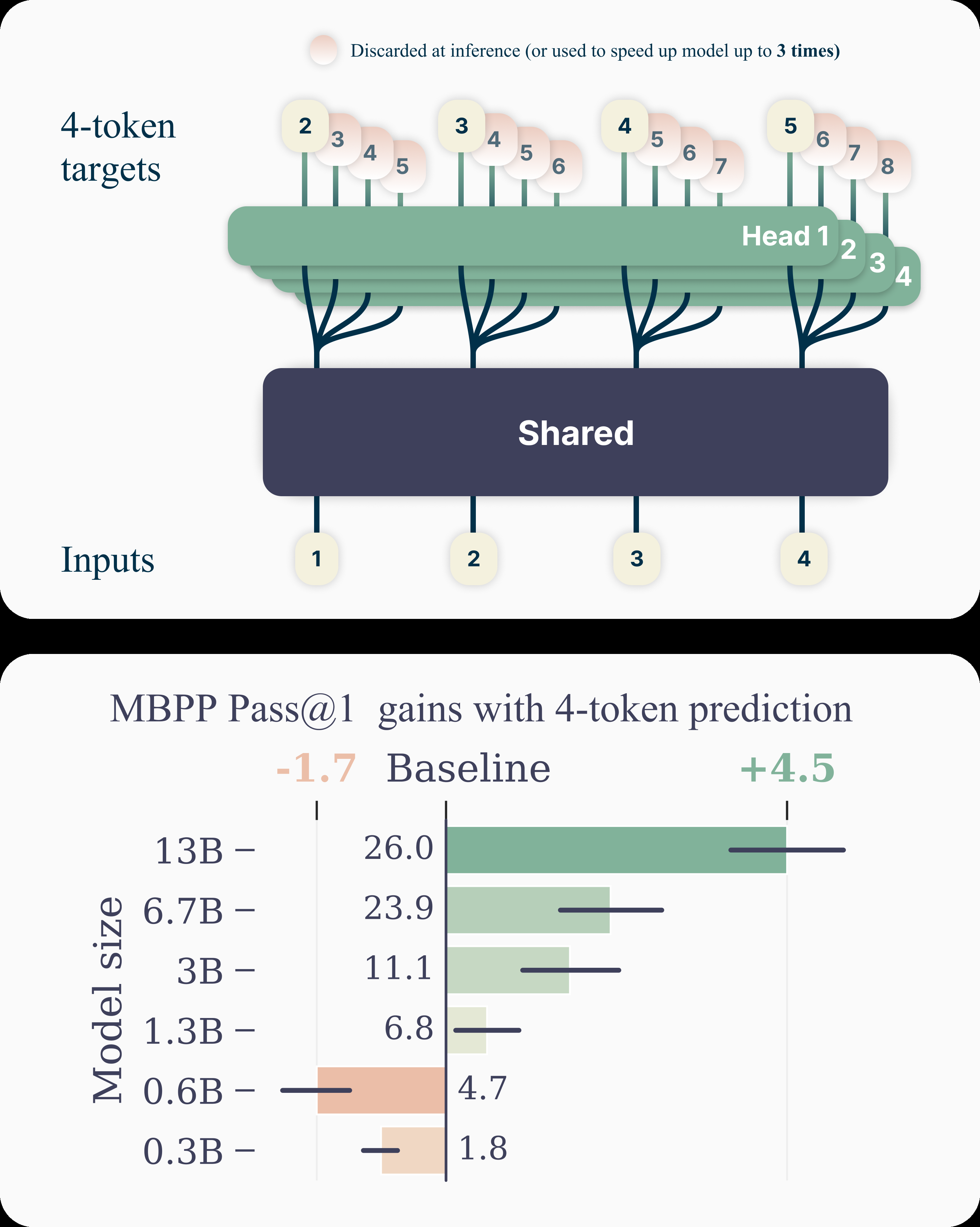

Figure 7: Multi-token prediction enables models to predict multiple future tokens simultaneously, improving both training efficiency and inference speed. Models trained with this approach "solve 12% more problems on HumanEval and 17% more on MBPP than comparable next-token models." (Source: Meta FAIR, 2024)

Figure 7: Multi-token prediction enables models to predict multiple future tokens simultaneously, improving both training efficiency and inference speed. Models trained with this approach "solve 12% more problems on HumanEval and 17% more on MBPP than comparable next-token models." (Source: Meta FAIR, 2024)

Security Applications: Detecting Malicious Code

An unexpected application of code world models is security verification. Research has shown that world models can detect malicious code by analyzing execution traces.

The Cross-Trace Verification Protocol (CTVP) uses CWM's execution predictions to check behavioral consistency. "By analyzing consistency patterns in these predicted traces, they detect behavioral anomalies indicative of backdoors." A model that genuinely understands execution can predict behavior across semantically equivalent program transformations; inconsistency reveals hidden functionality.

This security application validates that execution trace prediction captures meaningful behavior, not just superficial patterns. A world model that can detect backdoors must understand what code actually does.

Limitations and Open Questions

Code world models represent progress, but substantial limitations remain.

Computational Cost: Training on execution traces requires generating those traces, which means actually running code. This is expensive at scale and limits the diversity of training data compared to static code.

Language Coverage: Most work focuses on Python, which has straightforward execution semantics. Languages with complex compilation, static types, or concurrency present additional challenges. Understanding how world modeling principles transfer to Java, C++, or Rust remains unclear.

Long-Horizon Simulation: Execution traces can grow arbitrarily long. Current models handle limited horizons; simulating a program that runs for thousands of steps remains challenging.

Partial Code and Sketches: Real development often involves incomplete code, partial specifications, and iterative refinement. Whether execution understanding helps with these ambiguous cases is an open question.

What This Means for Engineering Practice

For software engineers evaluating AI-assisted development tools, code world models suggest several practical considerations.

Execution feedback matters: Tools that merely generate code without execution grounding will struggle with anything beyond simple completion tasks. Look for systems that incorporate test execution, static analysis, or behavioral feedback into their generation process.

Agentic frameworks need capable underlying models: SWE-agent and similar frameworks demonstrate that good agent-computer interfaces improve results. But the underlying model's code understanding determines the ceiling.

Benchmark skepticism is warranted: High numbers on SWE-bench or HumanEval indicate something about model capability, but deployment performance depends heavily on how well your use case matches the benchmark distribution.

The gap is closing but not closed: CWM's 65.8% on SWE-bench Verified is impressive compared to earlier models. It also means 34.2% of validated, relatively tractable issues remain unsolved. Real software engineering will be harder than benchmarks for the foreseeable future.

Looking Forward

Code world models represent a meaningful step toward AI systems that understand programs rather than merely generate them. The key insight from Ha and Schmidhuber's dreaming car carries through: models that learn to simulate their environment develop richer internal representations than those trained on static patterns alone.

For code, this means learning from execution traces, predicting variable states, and reasoning about program behavior. The benchmark results demonstrate that this approach works: execution-aware training produces models with genuinely different capabilities.

The remaining challenges are substantial. But the direction is clear. Models that understand execution will increasingly outperform those that only match patterns. For engineers building AI-assisted development tools, the implication is straightforward: prioritize execution feedback. Whether through world model training, test-driven generation, or iterative refinement with execution results, the systems that understand what code does will consistently outperform those that only know what code looks like.

The dreaming continues. What began with a car imagining race tracks has become an AI that imagines program execution.

References

-

Meta FAIR (2025). "CWM: An Open-Weights LLM for Research on Code Generation with World Models." arXiv:2510.02387

-

Ha, D., & Schmidhuber, J. (2018). "World Models." arXiv:1803.10122

-

Yang, J., Jimenez, C., Wettig, A., Lieret, K., Yao, S., Narasimhan, K., & Press, O. (2024). "SWE-agent: Agent-Computer Interfaces Enable Automated Software Engineering." arXiv:2405.15793

-

SWE-bench Plus Team (2024). "SWE-Bench+: Enhanced Coding Benchmark for LLMs." arXiv:2410.06992

-

LiveCodeBench Team (2024). "LiveCodeBench: Holistic and Contamination Free Evaluation of Large Language Models for Code." arXiv:2403.07974

-

Execution Traces Team (2025). "What I Cannot Execute, I Do Not Understand: Training and Evaluating LLMs on Program Execution Traces." arXiv:2503.05703

-

MCTS-Code Team (2024). "Generating Code World Models with Large Language Models Guided by Monte Carlo Tree Search." arXiv:2405.15383

-

Meta FAIR (2024). "Better & Faster Large Language Models via Multi-token Prediction." arXiv:2404.19737

-

Code World Model Security Team (2024). "The Double Life of Code World Models: Provably Unmasking Malicious Behavior Through Execution Traces." arXiv:2512.13821

-

Zhang, C., et al. (2024). "Meta-Task Planning for Language Agents." arXiv:2405.16510

-

Vaswani, A., et al. (2017). "Attention Is All You Need." arXiv:1706.03762