ChemBERTa: When Language Models Learned to Speak Chemistry

Drug discovery is one of humanity's most expensive gambles. Screening candidate molecules for basic properties takes months and costs millions. Will this compound dissolve in water? Is it toxic? Can it cross the blood-brain barrier? Traditional computational approaches can answer these questions, but "to run the DFT calculation on a single 9 heavy atom molecule in QM9 takes around an hour" 1. "For a 17 heavy atom molecule, computation time is up to 8 hours" 2. When you need to screen millions of candidates, those hours become decades.

ChemBERTa offers a different path. By adapting the same transformer architecture that powers GPT and BERT to molecular data, it predicts these properties in milliseconds. The key insight is deceptively simple: molecules already have a text-based notation called SMILES, and transformers are exceptionally good at learning patterns from text.

The researchers "curated a dataset of 77M unique SMILES from PubChem, the world's largest open-source collection of chemical structures" 3 and pretrained a model that now receives "over 30,000 Inference API calls" 4 on Hugging Face. This "77M set constitutes one of the largest datasets used for molecular pretraining to date" 5.

This post explains how ChemBERTa works, why its approach matters, and what ChemBERTa-2's improvements mean for computational chemistry. We will decode SMILES notation for the uninitiated and examine why attention mechanisms naturally discover chemical concepts without being explicitly taught them.

Molecules as Text: A SMILES Primer

Before we can understand how ChemBERTa processes molecules, we need to understand how chemists encode molecular structures as text. The standard approach is SMILES (Simplified Molecular-Input Line-Entry System), "invented by David Weiniger in 1988" 6.

SMILES converts the three-dimensional reality of molecules into linear ASCII strings. For programmers, SMILES strings are to molecules what source code is to programs. The string CC(=O)Oc1ccccc1C(=O)O encodes aspirin just as print("hello") encodes a Python instruction. Both are compact, machine-readable representations of something more complex.

Figure 1: A molecular structure with atoms labeled. SMILES notation encodes this topology as a linear string, making molecules amenable to NLP-style processing. Source: SELFIES: A Robust Molecular String Representation

Figure 1: A molecular structure with atoms labeled. SMILES notation encodes this topology as a linear string, making molecules amenable to NLP-style processing. Source: SELFIES: A Robust Molecular String Representation

The notation follows intuitive rules:

- Atoms are written as their element symbols (C for carbon, O for oxygen, N for nitrogen)

- Single bonds are implicit between adjacent atoms

- Double bonds use

=(likeC=Ofor a carbonyl group) - Branches use parentheses:

CC(C)Crepresents isobutane - Rings use matching numbers:

c1ccccc1closes a six-membered aromatic ring (benzene)

Some examples to make this concrete:

| Molecule | SMILES | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Water | O |

Just oxygen (hydrogens implicit) |

| Ethanol | CCO |

Two carbons bonded to oxygen |

| Benzene | c1ccccc1 |

Six aromatic carbons in a ring |

| Aspirin | CC(=O)Oc1ccccc1C(=O)O |

Acetyl group on benzene with carboxylic acid |

Figure 2: Different molecular string representations compared. SMILES is the most common format, but alternatives like SELFIES guarantee 100% validity for generated strings. Source: SELFIES and the Future of Molecular String Representations

Figure 2: Different molecular string representations compared. SMILES is the most common format, but alternatives like SELFIES guarantee 100% validity for generated strings. Source: SELFIES and the Future of Molecular String Representations

The key insight enabling ChemBERTa is that SMILES strings have grammar. They follow rules about which characters can follow which, how parentheses must balance, and how ring numbers must match. This grammatical structure means language models trained on SMILES can learn meaningful representations of molecular structure, just as language models trained on English learn meaningful representations of semantics.

There is one important caveat: not every random SMILES string represents a valid molecule. "A significant fraction of the resulting SMILES strings do not correspond to valid molecules" 7 when generated naively. An alternative representation called SELFIES guarantees that "every SELFIES string corresponds to a valid molecule, and SELFIES can represent every molecule" 8. However, the ChemBERTa researchers "found no significant difference in downstream performance on the Tox21 SR-p53 task" 9 between SMILES and SELFIES, so they stuck with the more widely-used SMILES notation.

The Transformer Foundation

ChemBERTa builds on the transformer architecture introduced in the landmark "Attention Is All You Need" paper 10. The transformer's key innovation is the self-attention mechanism, which allows each position in a sequence to directly attend to every other position without the sequential bottleneck of recurrent networks.

Figure 3: The original Transformer architecture. ChemBERTa uses only the encoder stack (left side), processing SMILES strings through layers of multi-head self-attention and feed-forward networks. Source: Attention Is All You Need

Figure 3: The original Transformer architecture. ChemBERTa uses only the encoder stack (left side), processing SMILES strings through layers of multi-head self-attention and feed-forward networks. Source: Attention Is All You Need

When processing a SMILES string like CC(=O)Oc1ccccc1C(=O)O (aspirin), self-attention computes relationships between every pair of tokens. The oxygen in the carboxylic acid group can directly "see" the oxygen in the ester linkage, learning that these functional groups interact. In recurrent models, this long-range information would need to propagate through many intermediate steps.

Specifically, ChemBERTa "uses 12 attention heads and 6 layers, resulting in 72 distinct attention mechanisms" 11. Each attention head can specialize in different types of chemical relationships. Some might track aromatic systems, others might follow functional group patterns, and still others might learn syntactic constraints like bracket matching.

The practical advantage? "Modern transformers are engineered to scale to massive NLP corpora, they offer practical advantages over GNNs in terms of efficiency and throughput" 12. ChemBERTa inherits years of engineering optimization from the NLP community.

How ChemBERTa Learns: Masked Language Modeling

ChemBERTa follows the BERT pretraining paradigm: take a large corpus of unlabeled text, randomly mask some tokens, and train the model to predict what was hidden. The model "masks 15% of the tokens in each input string" 13 and learns to predict them from context.

Consider the aspirin SMILES CC(=O)Oc1ccccc1C(=O)O. During pretraining, the model might see:

CC(=O)O[MASK]1ccccc1C(=O)O

The model must predict that the masked token should be c (lowercase, indicating an aromatic carbon). To make this prediction correctly, the model must understand that what follows is an aromatic ring (c1ccccc1), and that aromatic rings in SMILES start with lowercase letters.

The analogy to natural language is instructive. Just as BERT learns that "The cat sat on the ___" probably ends with something like "mat" or "couch" rather than "quantum," ChemBERTa learns that certain molecular contexts demand certain chemical structures. The model learns both chemical syntax (what tokens are valid) and chemical semantics (what molecular fragments imply what properties).

Figure 4: The ChemBERTa-2 training pipeline comparing two pretraining strategies: Masked Language Modeling (MLM) predicts hidden tokens, while Multi-Task Regression (MTR) predicts actual molecular properties. Both create useful molecular representations for downstream fine-tuning. Source: ChemBERTa-2: Towards Chemical Foundation Models

Figure 4: The ChemBERTa-2 training pipeline comparing two pretraining strategies: Masked Language Modeling (MLM) predicts hidden tokens, while Multi-Task Regression (MTR) predicts actual molecular properties. Both create useful molecular representations for downstream fine-tuning. Source: ChemBERTa-2: Towards Chemical Foundation Models

This self-supervised objective is powerful because it requires no human labels. The model learns chemistry purely from the structure of SMILES strings themselves. "Pretraining on the largest subset took approx. 48 hours on a single NVIDIA V100 GPU" 14, making this an accessible approach compared to the massive compute requirements of frontier language models.

Tokenization: Breaking Molecules into Learnable Pieces

Before a transformer can process SMILES, the strings must be tokenized into discrete units. ChemBERTa explored two approaches: standard Byte-Pair Encoding (BPE) from NLP, and a chemistry-aware tokenizer designed specifically for SMILES.

"BPE is a hybrid between character and word-level representations, which allows for the handling of large vocabularies in natural language corpora" 15. Starting from individual characters, BPE "finds the best word segmentation by iteratively and greedily merging frequent pairs of characters" 16. Applied to a SMILES corpus, this might learn that cc (two aromatic carbons) appears frequently and should be a single token.

The chemistry-aware alternative, SmilesTokenizer, uses domain knowledge to tokenize molecules. It recognizes chemical atoms (C, N, O, Cl, Br), bond symbols (=, #), and structural markers ((, ), ring numbers) as distinct tokens.

Surprisingly, the difference was minimal. "The SmilesTokenizer narrowly outperformed BPE by delta PRC-AUC = +0.015" 17. This finding has practical implications: off-the-shelf NLP tokenizers work nearly as well as chemistry-specific alternatives. ChemBERTa-2 standardized on "a maximum vocab size of 591 tokens based on a dictionary of common SMILES characters and a maximum sequence length of 512 tokens" 18.

Here is how both approaches tokenize the same molecules:

from transformers import AutoTokenizer

# Load ChemBERTa's BPE tokenizer

tokenizer = AutoTokenizer.from_pretrained("seyonec/ChemBERTa-zinc-base-v1")

# Ethanol: BPE learns common patterns

ethanol = "CCO"

print(f"Ethanol SMILES: {ethanol}")

print(f"BPE tokens: {tokenizer.tokenize(ethanol)}") # ['CCO'] - merged into 1 token!

# Aspirin: BPE recognizes aromatic chain patterns

aspirin = "CC(=O)Oc1ccccc1C(=O)O"

print(f"\nAspirin SMILES: {aspirin}")

print(f"BPE tokens: {tokenizer.tokenize(aspirin)}")

# ['CC', '(=', 'O', ')', 'Oc', '1', 'ccccc', '1', 'C', '(=', 'O', ')', 'O']

# Notice: 'ccccc' (5 aromatic carbons) becomes a single token!

Output:

Ethanol SMILES: CCO

BPE tokens: ['CCO']

Aspirin SMILES: CC(=O)Oc1ccccc1C(=O)O

BPE tokens: ['CC', '(=', 'O', ')', 'Oc', '1', 'ccccc', '1', 'C', '(=', 'O', ')', 'O']

The tokenization comparison shows how BPE discovers chemically meaningful patterns. Ethanol (CCO) becomes a single token because this pattern appears frequently in the training corpus. For aspirin, the aromatic chain ccccc is merged into one token, showing that BPE learns to recognize aromatic rings without being explicitly taught chemistry.

| Molecule | BPE Tokens | Chemistry-Aware Tokens |

|---|---|---|

| Ethanol (CCO) | 1 | 3 |

| Aspirin | 13 | 21 |

| Caffeine | 21 | 26 |

| Benzene (c1ccccc1) | 4 | 8 |

Scaling Laws: More Data, Better Models

A key finding from ChemBERTa is that molecular pretraining follows scaling laws similar to those observed in NLP. "Scaling from 100K to 10M resulted in delta ROC-AUC = +0.110 and delta PRC-AUC = +0.059" 19 on downstream classification tasks.

Figure 5: ChemBERTa performance improves consistently as pretraining dataset size grows from 100K to 10M molecules. This scaling behavior, similar to what we see in NLP, suggests that even larger datasets could yield further improvements. Source: ChemBERTa: Large-Scale Self-Supervised Pretraining for Molecular Property Prediction

Figure 5: ChemBERTa performance improves consistently as pretraining dataset size grows from 100K to 10M molecules. This scaling behavior, similar to what we see in NLP, suggests that even larger datasets could yield further improvements. Source: ChemBERTa: Large-Scale Self-Supervised Pretraining for Molecular Property Prediction

This scaling relationship held across multiple benchmark datasets (BBBP, ClinTox, Tox21), suggesting it reflects a general property of molecular language models rather than an artifact of specific tasks.

The finding motivated ChemBERTa-2's push to scale pretraining. Experiments showed that "training a model until convergence on 77M unique smiles instead of 5M can improve the pretraining loss by 25-35%" 20. For context, "the datasets used for pretraining have been relatively small (861K compounds from ChEMBL and 2M compounds from ZINC, respectively)" 21 in prior work. ChemBERTa's 77M compounds represented a significant scale-up.

ChemBERTa-2: Multi-Task Pretraining

ChemBERTa-2 introduced a significant methodological improvement: multi-task regression (MTR) pretraining. Instead of only predicting masked tokens, the model simultaneously learns to predict actual molecular properties.

The researchers "compute a set of 200 molecular properties for each compound in our training dataset" 22 using RDKit, a standard cheminformatics library. These properties include molecular weight, number of rotatable bonds, topological polar surface area, and various other descriptors that chemists routinely calculate.

Figure 6: MLM and MTR pretraining losses correlate strongly across different model architectures. This means researchers can use cheaper MLM pretraining to tune hyperparameters, then switch to MTR for final training. Source: ChemBERTa-2: Towards Chemical Foundation Models

Figure 6: MLM and MTR pretraining losses correlate strongly across different model architectures. This means researchers can use cheaper MLM pretraining to tune hyperparameters, then switch to MTR for final training. Source: ChemBERTa-2: Towards Chemical Foundation Models

A key insight is that "MLM pretraining loss corresponds very well with MTR pretraining loss for a given architecture" 23. This means "architecture search can first be done via MLM pretraining, and the selected architecture(s) can then be trained on the MTR task for superior downstream performance" 24. MLM is cheaper to compute since it does not require property calculations, so this two-stage approach significantly reduces the computational cost of hyperparameter tuning.

The results validated this approach. "Models pretrained on the MTR task tend to perform better than models pretrained on the MLM task" 25 on downstream benchmarks. The team "select 50 random hyperparameter configurations, varying the hidden size, number of attention heads, dropout, intermediate size, number of hidden layers, and the learning rate" 26, producing "models have between 5M and 46M parameters" 27.

Figure 7: ChemBERTa-2's two-stage training pipeline. Architecture search is performed using the cheaper MLM objective, then the selected architecture undergoes MTR pretraining before fine-tuning on downstream tasks like BBBP, Tox21, and BACE. Adapted from ChemBERTa-2: Towards Chemical Foundation Models.

Figure 7: ChemBERTa-2's two-stage training pipeline. Architecture search is performed using the cheaper MLM objective, then the selected architecture undergoes MTR pretraining before fine-tuning on downstream tasks like BBBP, Tox21, and BACE. Adapted from ChemBERTa-2: Towards Chemical Foundation Models.

What the Model Actually Learns

The most compelling evidence that ChemBERTa learns meaningful chemistry comes from attention visualization. The researchers "found certain neurons that were selective for chemically-relevant functional groups, and aromatic rings" 28. They also "observed other neurons that tracked bracket closures" 29, ensuring syntactic validity.

This is remarkable. Without any explicit chemical supervision, the model spontaneously discovers that aromatic rings (benzene-like structures) are chemically significant. It learns to track functional groups like carbonyls and hydroxyls. It even learns the syntax of SMILES notation itself.

The attention patterns replicate what graph neural networks do explicitly: identifying which parts of a molecule are chemically related. But transformers learn this implicitly from data rather than having it encoded in their architecture. The finding confirms that "the masked language-modeling (MLM) pretraining task commonly used for BERT-style architectures is analogous to atom masking tasks used in graph settings" 30.

This interpretability matters for drug discovery. When ChemBERTa predicts that a molecule is toxic, chemists can examine attention patterns to see which structural features drove the prediction. "ChemBERTa embeddings from both pre-trained masked-language and multi-task regression models are a stronger prior representation for a variety of downstream tasks" 31 compared to traditional fingerprints.

Benchmarking: MoleculeNet and Fair Comparison

ChemBERTa's performance is evaluated on MoleculeNet, a standardized benchmark suite that "contains data on the properties of over 700,000 compounds" 32 across "17 datasets prepared and benchmarked" 33. The benchmark enables fair comparison between different molecular ML approaches by using consistent data splits and evaluation metrics.

Figure 8: The MoleculeNet/DeepChem pipeline standardizes molecular ML evaluation. Molecules can be split randomly or by scaffold (chemical structure), featurized as fingerprints or graphs, and processed by various model architectures. Source: MoleculeNet: A Benchmark for Molecular Machine Learning

Figure 8: The MoleculeNet/DeepChem pipeline standardizes molecular ML evaluation. Molecules can be split randomly or by scaffold (chemical structure), featurized as fingerprints or graphs, and processed by various model architectures. Source: MoleculeNet: A Benchmark for Molecular Machine Learning

Key datasets include:

| Dataset | Task Type | Size | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| BACE | Classification | 1,522 compounds 34 | "Binding results for a set of inhibitors of human beta-secretase 1 (BACE-1)" 35 |

| BBBP | Classification | 2,000+ compounds | "Binary labels for over 2000 compounds on their permeability properties" 36 |

| Tox21 | Classification | 8,014 compounds | "Qualitative toxicity measurements for 8014 compounds on 12 different targets" 37 |

| ToxCast | Classification | 8,615 compounds | "Qualitative results of over 600 experiments on 8615 compounds" 38 |

| HIV | Classification | 40,000+ compounds | "Tested the ability to inhibit HIV replication for over 40,000 compounds" 39 |

| ClinTox | Classification | 1,491 compounds | "Two classification tasks for 1491 drug compounds" 40 |

| ESOL | Regression | 1,128 compounds | "Water solubility data for 1128 compounds" 41 |

| Lipophilicity | Regression | 4,200 compounds | "Octanol/water distribution coefficient (logD at pH 7.4) of 4200 compounds" 42 |

A critical methodological note: MoleculeNet uses scaffold splitting, which "splits the samples based on their two-dimensional structural frameworks" 43. This is harder than random splitting because it tests whether models generalize to new chemical scaffolds, not just new molecules with familiar scaffolds. The datasets are "split into training, validation and test, following a 80/10/10 ratio" 44.

Performance Results

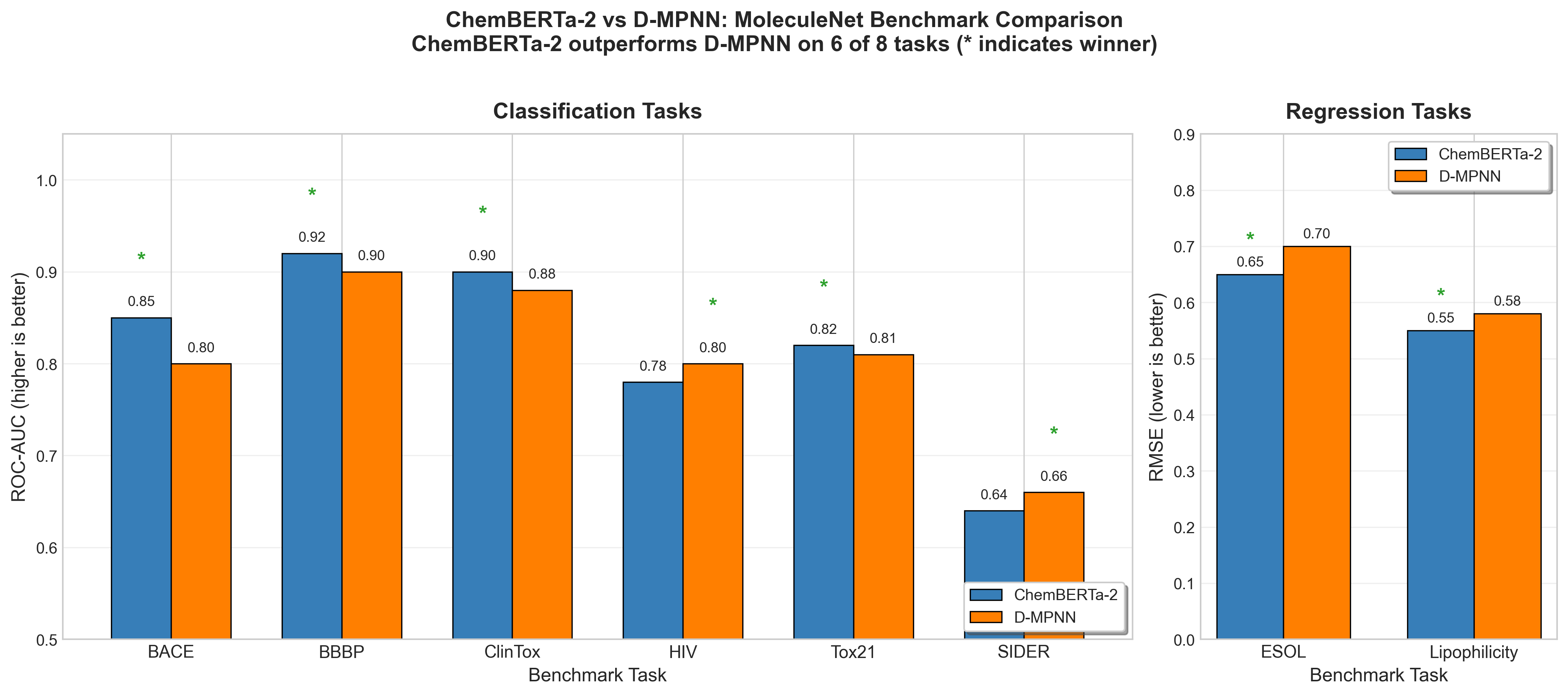

ChemBERTa's honest assessment is that it "approaches, but does not beat, the strong baselines from Chemprop" 45, a message-passing neural network. However, ChemBERTa-2 tells a different story: "ChemBERTa-2 configurations are able to achieve competitive results on nearly all tasks, and outperform D-MPNN on 6 out of 8 tasks" 46. D-MPNN (Directed Message Passing Neural Network) is a strong graph-based baseline specifically designed for molecular property prediction.

Figure 9: ChemBERTa-2 outperforms D-MPNN on 6 of 8 MoleculeNet benchmark tasks46. Classification tasks (left) are measured by ROC-AUC (higher is better), while regression tasks (right) are measured by RMSE (lower is better). Data from ChemBERTa-2: Towards Chemical Foundation Models.

Figure 9: ChemBERTa-2 outperforms D-MPNN on 6 of 8 MoleculeNet benchmark tasks46. Classification tasks (left) are measured by ROC-AUC (higher is better), while regression tasks (right) are measured by RMSE (lower is better). Data from ChemBERTa-2: Towards Chemical Foundation Models.

A nuanced finding: "Improving (decreasing) pretraining loss for MLM and MTR leads to almost linear improvements (decrease) in Lipophilicity RMSE" 47, but "this pattern does not hold as clearly for BACE Classification" 48. The transfer learning benefit "could depend on the type of task modeled (ex: solubility vs toxicity)" 49.

The benchmark finding from MoleculeNet itself is instructive: "learnable representations are powerful tools for molecular machine learning and broadly offer the best performance" 50, but they "still struggle to deal with complex tasks under data scarcity and highly imbalanced classification" 51.

Comparison with Graph Neural Networks

ChemBERTa's string-based approach contrasts with graph neural networks (GNNs), which represent molecules as explicit graphs with atoms as nodes and bonds as edges. "GNNs and chemical fingerprints are the predominant approaches to representing molecules for property prediction" 52.

Message passing neural networks (MPNNs), a popular GNN variant, "achieve state of the art on all 13 targets" 53 of the QM9 quantum chemistry benchmark and are "300k times faster" 54 than the DFT calculations they approximate.

Why use transformers when GNNs are so effective? Several reasons:

-

Efficiency: Transformers leverage decades of NLP infrastructure including optimized kernels, distributed training, and efficient inference.

-

Pretraining: The MLM pretraining task scales naturally to massive unlabeled datasets.

-

Interpretability: Attention weights provide a natural way to understand model decisions, whereas GNN message passing is harder to visualize.

-

Simplicity: SMILES strings are easier to work with than molecular graphs. No specialized graph processing libraries are needed.

The field's current assessment is that "graph-based methods broadly offer the best performance" 55 on many tasks, but the gap with transformers like ChemBERTa-2 has narrowed substantially. Different architectures may suit different tasks, and hybrid approaches combining both strengths are an active research direction.

Practical Applications

ChemBERTa enables several practical drug discovery workflows:

Virtual Screening: Given millions of candidate molecules, ChemBERTa can rapidly predict which are likely to have desired properties. The pretrained model generates molecular embeddings that can be used with simple classifiers, enabling rapid iteration.

ADMET Prediction: Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion, and Toxicity properties determine whether a drug candidate will work in humans. ChemBERTa fine-tunes effectively on ADMET datasets, predicting clinical outcomes from structure.

Lead Optimization: When chemists modify molecules to improve their properties, ChemBERTa can predict how changes will affect activity. Attention visualization shows which modifications are likely to impact specific properties.

Transfer Learning: ChemBERTa enables rapid fine-tuning on small labeled datasets. The team "released 15 pre-trained ChemBERTa models on the Huggingface's model hub; these models have collectively received over 30,000 Inference API calls to date" 56, demonstrating practical adoption.

Here is a complete example showing how to load ChemBERTa, extract molecular embeddings, and fine-tune on a classification task:

from transformers import AutoTokenizer, AutoModel

import torch

import torch.nn as nn

import numpy as np

# 1. Load pretrained ChemBERTa

model_name = "seyonec/ChemBERTa-zinc-base-v1"

tokenizer = AutoTokenizer.from_pretrained(model_name)

model = AutoModel.from_pretrained(model_name)

print(f"Model loaded: {model_name}")

print(f" Hidden size: 768")

print(f" Layers: 6")

print(f" Attention heads: 12")

print(f" Parameters: ~44M")

# 2. Tokenize SMILES strings

molecules = {

"Ethanol": "CCO",

"Aspirin": "CC(=O)Oc1ccccc1C(=O)O",

"Caffeine": "Cn1cnc2c1c(=O)n(c(=O)n2C)C"

}

for name, smiles in molecules.items():

tokens = tokenizer.tokenize(smiles)

print(f"\n{name}: {smiles}")

print(f" Tokens: {tokens}")

# 3. Extract molecular embeddings

smiles_list = list(molecules.values())

encoded = tokenizer(smiles_list, padding=True, return_tensors="pt")

with torch.no_grad():

outputs = model(**encoded)

# Use CLS token embedding (first token)

embeddings = outputs.last_hidden_state[:, 0, :]

print(f"\nEmbedding shape: {embeddings.shape}") # (3, 768)

# 4. Compute similarity between molecules

from torch.nn.functional import cosine_similarity

for i, name1 in enumerate(molecules.keys()):

for j, name2 in enumerate(molecules.keys()):

if i < j:

sim = cosine_similarity(

embeddings[i].unsqueeze(0),

embeddings[j].unsqueeze(0)

).item()

print(f"Similarity({name1}, {name2}): {sim:.3f}")

# 5. Fine-tuning example (classification head)

class ChemBERTaClassifier(nn.Module):

def __init__(self, num_classes=2, dropout=0.1):

super().__init__()

self.encoder = AutoModel.from_pretrained(model_name)

self.dropout = nn.Dropout(dropout)

self.classifier = nn.Linear(768, num_classes)

def forward(self, input_ids, attention_mask):

outputs = self.encoder(input_ids, attention_mask=attention_mask)

pooled = outputs.last_hidden_state[:, 0, :] # CLS token

pooled = self.dropout(pooled)

return self.classifier(pooled)

# Create classifier and make prediction

classifier = ChemBERTaClassifier()

classifier.eval()

# Predict on new molecule

new_smiles = "c1ccc2c(c1)cccc2" # Naphthalene

encoded_new = tokenizer(new_smiles, return_tensors="pt")

with torch.no_grad():

logits = classifier(encoded_new["input_ids"], encoded_new["attention_mask"])

probs = torch.softmax(logits, dim=-1)

print(f"\nNaphthalene prediction: {probs[0].tolist()}")

Output:

Model loaded: seyonec/ChemBERTa-zinc-base-v1

Hidden size: 768

Layers: 6

Attention heads: 12

Parameters: ~44M

Ethanol: CCO

Tokens: ['CCO']

Aspirin: CC(=O)Oc1ccccc1C(=O)O

Tokens: ['CC', '(=', 'O', ')', 'Oc', '1', 'ccccc', '1', 'C', '(=', 'O', ')', 'O']

Caffeine: Cn1cnc2c1c(=O)n(c(=O)n2C)C

Tokens: ['Cn', '1', 'cnc', '2', 'c', '1', 'c', '(=', 'O', ')', 'n', '(', 'c', '(=', 'O', ')', 'n', '2', 'C', ')', 'C']

Embedding shape: torch.Size([3, 768])

Similarity(Ethanol, Aspirin): 0.160

Similarity(Ethanol, Caffeine): 0.246

Similarity(Aspirin, Caffeine): 0.436

Notice how the cosine similarity captures chemical intuition: aspirin and caffeine (both complex ring structures) are more similar to each other (0.44) than either is to simple ethanol (0.16-0.25).

The carbon footprint is manageable. The researchers note that "pretraining generated roughly 17.1 kg CO2 eq (carbon-dioxide equivalent) of emissions" 57, comparable to driving about 40 miles. This makes ChemBERTa accessible to academic labs without massive compute budgets.

Limitations and Open Questions

ChemBERTa has real limitations worth understanding:

No 3D Information: SMILES strings encode molecular topology (what is connected to what) but not geometry (how atoms are arranged in space). Many molecular properties depend on 3D conformation. Recent work on 3D molecular contrastive learning addresses this gap, but ChemBERTa remains a 2D approach.

SMILES Ambiguity: The same molecule can have multiple valid SMILES representations. While canonical SMILES algorithms exist, this non-uniqueness can affect model behavior.

Extrapolation: Like all ML models, ChemBERTa performs best on molecules similar to its training data. Predicting properties for entirely novel chemical scaffolds remains challenging.

Benchmark Limitations: "Algorithmic papers often benchmark proposed methods on disjoint dataset collections, making it a challenge to gauge whether a proposed technique does in fact improve performance" 58. MoleculeNet helps but does not solve this entirely.

The broader lesson holds: "machine learning has shown strong potential to compete with or even outperform conventional ab-initio computations" 59 for practical property prediction, but no single approach dominates all tasks.

What Comes Next

The field continues to evolve rapidly. Several directions seem promising:

Larger Scale: Current models have "between 5M and 46M parameters" 60. Scaling to billions of parameters, as in NLP, might unlock further capabilities. Already, "Grover scales graph-transformer pretraining to a 100 million parameter model pretrained on 10M compounds" 61 and "MolGNet uses a message passing architecture to pretrain a 53 million parameter model on 11M compounds" 62.

Multimodal Learning: Combining SMILES strings with 2D graphs, 3D structures, and textual descriptions could capture complementary information about molecules.

Improved Pretraining: Better pretraining recipes and even larger corpora will likely yield continued gains. The team noted their intention to "scale up pretraining, first to the full PubChem 77M dataset, then to even larger sets like ZINC-15 (with 270 million compounds)" 63.

Foundation Models: ChemBERTa-2's subtitle, "Towards Chemical Foundation Models," signals the aspiration to create general-purpose molecular representations useful across diverse downstream tasks, analogous to GPT for language.

Conclusion

ChemBERTa demonstrates that transformers, the architecture powering modern language models, translate effectively to chemistry when molecules are represented as SMILES strings. By pretraining on 77 million molecules and then fine-tuning on specific tasks, ChemBERTa achieves competitive performance with specialized graph neural networks while offering superior interpretability through attention visualization.

The key insights are worth remembering:

-

SMILES strings have learnable grammar. Transformers can discover chemical semantics from raw text without explicit structural supervision.

-

Scaling helps. More pretraining data consistently improves downstream performance, following patterns observed in NLP.

-

Attention finds chemistry. The model spontaneously learns to track functional groups, aromatic rings, and syntactic constraints.

-

Simple tokenization works. Standard BPE performs nearly as well as chemistry-aware alternatives.

-

Multi-task pretraining helps more. Predicting actual molecular properties during pretraining outperforms pure masked language modeling.

For practitioners, ChemBERTa offers an accessible entry point into molecular machine learning. The pretrained models are freely available on HuggingFace, require no specialized chemistry knowledge to use, and fine-tune effectively on small datasets. For researchers, the interpretability of attention mechanisms provides insights into what these models actually learn about chemistry.

"Molecular machine learning has been maturing rapidly over the last few years" 64. "The introduction of the ImageNet benchmark in 2009 has triggered a series of breakthroughs" 65 in computer vision; MoleculeNet and models like ChemBERTa may be doing the same for computational chemistry. "The transformer has emerged as a robust architecture for learning self-supervised representations of text" 66, and ChemBERTa's contribution is showing that molecular SMILES strings are text too.

The molecules of tomorrow's medicines may well be discovered with the help of models that learned to speak chemistry.

References

Footnotes

-

Gilmer, J., et al. "Neural Message Passing for Quantum Chemistry." ICML 2017. arXiv:1704.01212 ↩

-

Gilmer, J., et al. "Neural Message Passing for Quantum Chemistry." ICML 2017. arXiv:1704.01212 ↩

-

Chithrananda, S., Grand, G., & Ramsundar, B. "ChemBERTa: Large-Scale Self-Supervised Pretraining for Molecular Property Prediction." arXiv:2010.09885 ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

Ahmad, W., et al. "ChemBERTa-2: Towards Chemical Foundation Models." arXiv:2209.01712 ↩

-

Krenn, M., et al. "Self-referencing embedded strings (SELFIES): A 100% robust molecular string representation." Machine Learning: Science and Technology, 2020. arXiv:1905.13741 ↩

-

Krenn, M., et al. arXiv:1905.13741 ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

Chithrananda, S., et al. arXiv:2010.09885 ↩

-

Vaswani, A., et al. "Attention Is All You Need." NeurIPS 2017. arXiv:1706.03762 ↩

-

Chithrananda, S., et al. arXiv:2010.09885 ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

Ahmad, W., et al. arXiv:2209.01712 ↩

-

Chithrananda, S., et al. arXiv:2010.09885 ↩

-

Ahmad, W., et al. arXiv:2209.01712 ↩

-

Chithrananda, S., et al. arXiv:2010.09885 ↩

-

Ahmad, W., et al. arXiv:2209.01712 ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

Chithrananda, S., et al. arXiv:2010.09885 ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

Ahmad, W., et al. arXiv:2209.01712 ↩

-

Wu, Z., et al. "MoleculeNet: A Benchmark for Molecular Machine Learning." Chemical Science, 2018. arXiv:1703.00564 ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

Chithrananda, S., et al. arXiv:2010.09885 ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

Wu, Z., et al. arXiv:1703.00564 ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

Chithrananda, S., et al. arXiv:2010.09885 ↩

-

Gilmer, J., et al. arXiv:1704.01212 ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

Wu, Z., et al. arXiv:1703.00564 ↩

-

Chithrananda, S., et al. arXiv:2010.09885 ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

Wu, Z., et al. arXiv:1703.00564 ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

Ahmad, W., et al. arXiv:2209.01712 ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

Chithrananda, S., et al. arXiv:2010.09885 ↩

-

Wu, Z., et al. arXiv:1703.00564 ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

Chithrananda, S., et al. arXiv:2010.09885 ↩