When SWE-bench was released, even state-of-the-art models achieved only 1.96% success on real GitHub issues.1 Today, RL-trained models have pushed that number dramatically higher through reinforcement learning, where test execution acts as an automated referee. The model writes code, runs tests, receives clear success or failure signals, and improves. No human evaluation required. No ambiguous scoring rubrics. Just: does the test pass?

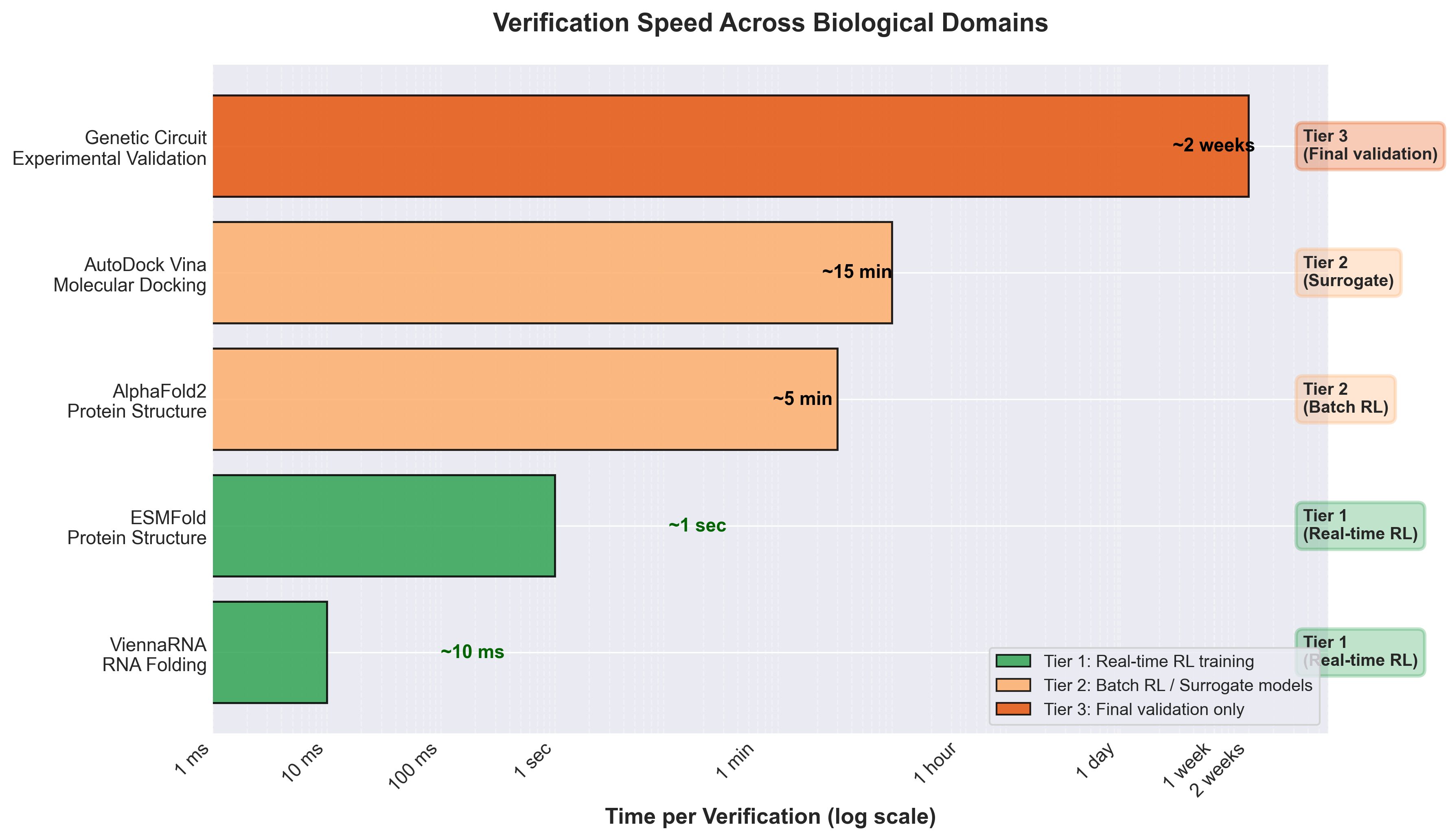

This pattern of automated verification of complex tasks is exactly what makes biology an ideal training ground for reinforcement learning agents. Not benchmarks for evaluating pre-trained models, but environments for training them from scratch. The difference matters: training needs millions of trials with instant feedback. Biology provides physics-based referees that can verify solutions quickly, from milliseconds for RNA folding to seconds for protein structure prediction.

Here's the fundamental insight: biological design problems are inverse problems with computable solutions. Given a protein structure, AlphaFold can verify if your generated sequence folds correctly. Given an RNA target structure, ViennaRNA can score your design in milliseconds using thermodynamic calculations.2 Given a molecule, docking algorithms can predict binding affinity to target proteins. These aren't approximate human judgments: they're deterministic simulations grounded in physical laws.

The Verification Problem in Current AI Benchmarks

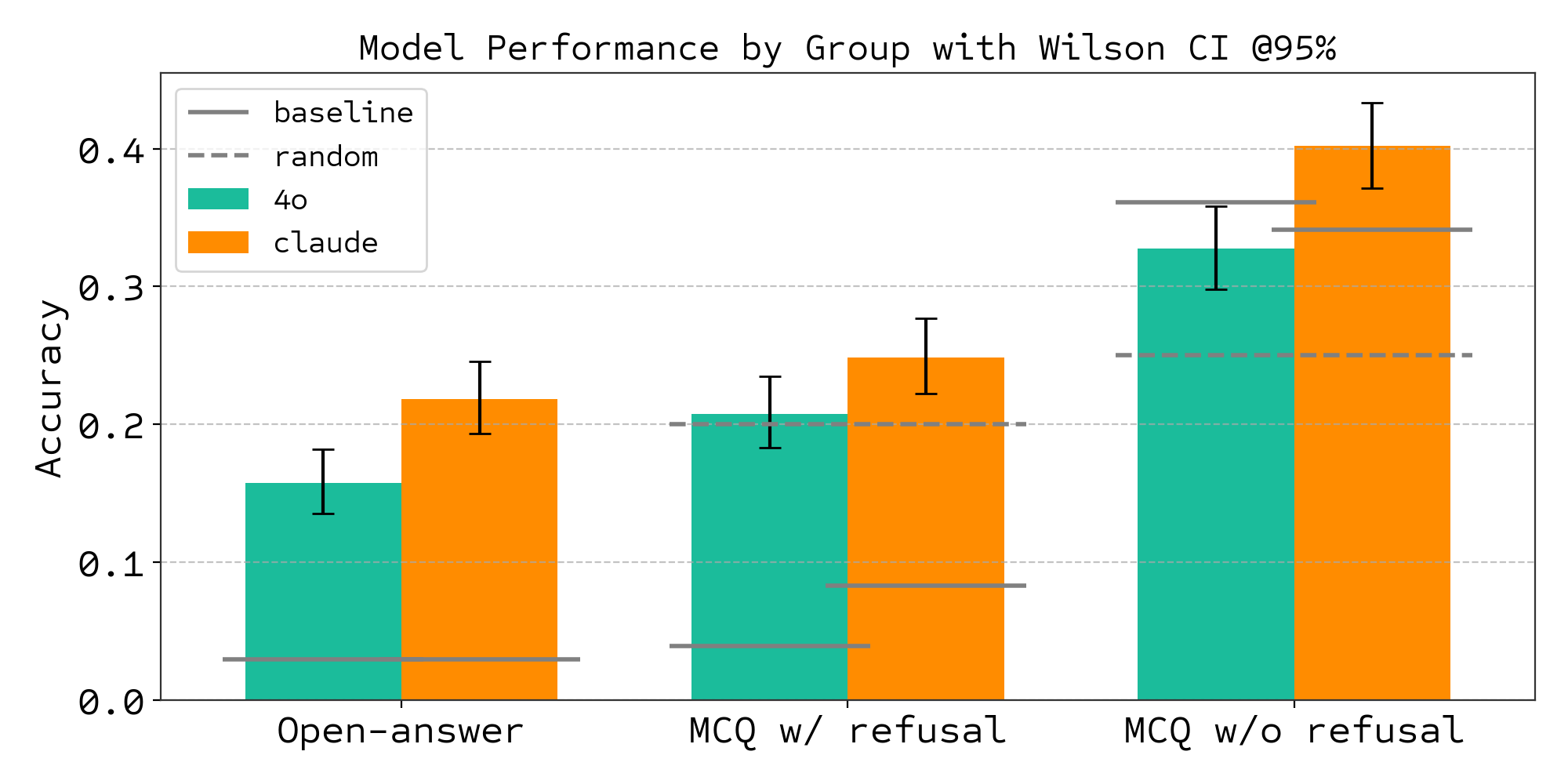

Most AI benchmarks fail as training environments because they lack automated verification. Consider how we currently evaluate language models on scientific tasks. BixBench, which tests LLMs on biological data analysis, revealed the gap: "We find that even the latest frontier models achieve only 21% accuracy in the open-answer regime, and marginally better than random in a multiple-choice setting."3

When Claude 3.5 Sonnet achieves 21% accuracy and GPT-4o manages 15% on open-ended scientific analysis, how do we generate the millions of training examples needed for RL? Human evaluation doesn't scale.

Software engineering cracked this through test-driven development. SWE-bench sources task instances from real-world Python repositories by connecting GitHub issues to merged pull request solutions that resolve related tests.4 Biology can do the same through physics-driven verification, and often faster.

What Makes a Benchmark RL-Ready?

Not every benchmark supports RL training. Three requirements distinguish training environments from evaluation benchmarks:

Requirement 1: Automated Verification

Results must be scored programmatically without human judgment. Benchmarking best practices demand you "Execute benchmarks 5-10 times with different random seeds" and "Present standard deviations or 95% confidence intervals, not just means."5 For training, you need this for every trial, not just final evaluation.

Requirement 2: Defined State and Action Spaces

The agent needs clear representations of problems and solutions. In protein design, the state is a target structure (3D coordinates), actions are amino acid selections, and the reward comes from folding simulation. The action space must be large enough for meaningful exploration but structured enough for learning.

Requirement 3: Anti-Memorization Properties

Training environments must resist simple dataset memorization. The search space should be large enough that agents must learn principles, not just memorize solutions. Protein design research demonstrates this naturally: researchers "Generated diverse sequences with only 10-30% similarity to natural proteins" while still achieving "TM-scores >0.6 across five target folds."6 The space of valid proteins vastly exceeds any training set.

Biology excels at all three, as the following domain examples demonstrate.

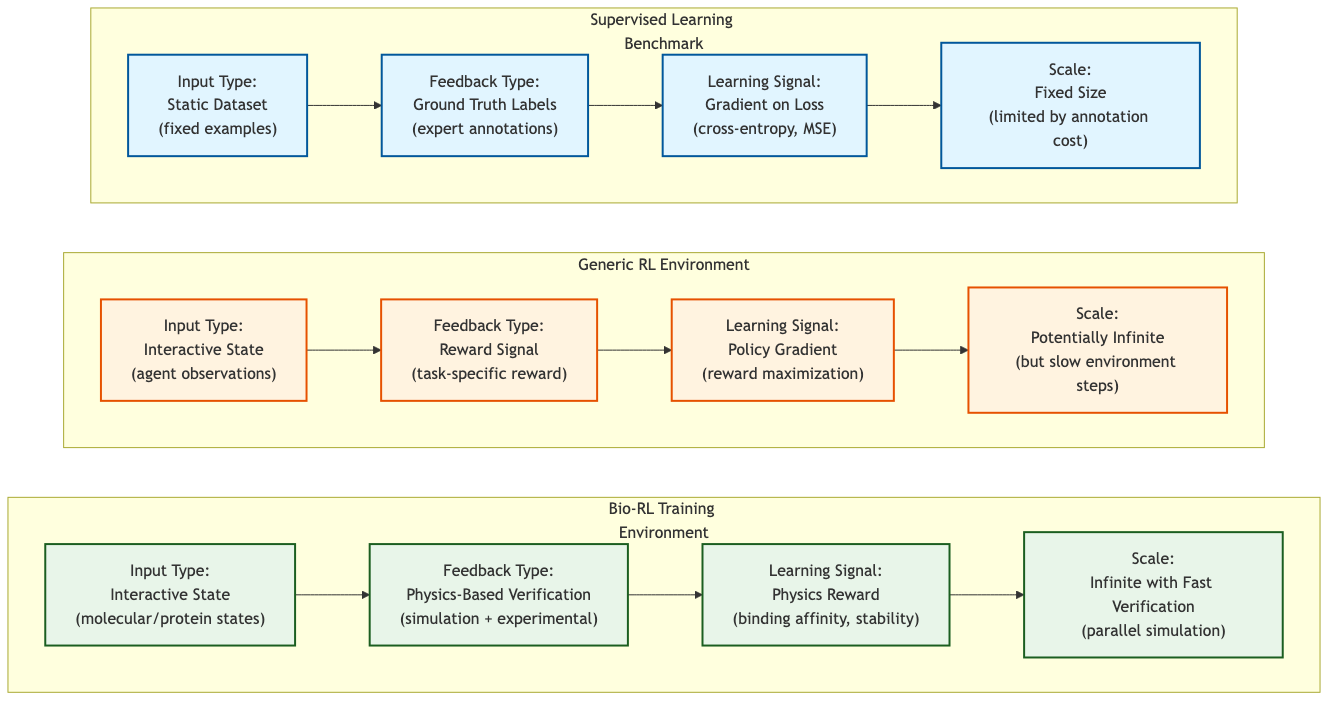

Figure 1: Comparison of learning paradigms showing how Bio-RL environments combine the interactivity of RL with physics-based verification for infinite-scale training. (Author's illustration)

Figure 1: Comparison of learning paradigms showing how Bio-RL environments combine the interactivity of RL with physics-based verification for infinite-scale training. (Author's illustration)

Protein Inverse Folding: AlphaFold as Referee

The protein design problem: given a backbone structure (3D coordinates), generate an amino acid sequence that folds into that structure. The verification: predict the structure using AlphaFold and compare to your target.

ProteinMPNN achieves approximately 52% sequence recovery on native protein backbones.7 That's the baseline for sequence recovery. But the real power emerges when you move beyond sequence recovery to structural verification.

Figure 2: AlphaFold's neural network architecture enables accurate structure prediction, serving as an automated verifier for protein design tasks. Source: Highly accurate protein structure prediction with AlphaFold

Figure 2: AlphaFold's neural network architecture enables accurate structure prediction, serving as an automated verifier for protein design tasks. Source: Highly accurate protein structure prediction with AlphaFold

The ProteinInvBench framework integrates multiple models systematically: "KWDesign and PiFold are the best and second-best models" on standard benchmarks.8 What makes these benchmarks work for RL is the generalization requirement: test sets use distinct structural domains and sequence identity filters below 30%, forcing models to learn physical principles of protein folding rather than memorize training examples.

The verification step runs fast enough for training. ESMFold provides dramatically faster structure predictions than AlphaFold2, enabling real-time verification during training.9 You can evaluate thousands of designs per hour. Compare this to experimental validation: "Of 39 designs tested biochemically, only 7 folded successfully in vitro"10: an 18% success rate taking weeks of lab work.

RL training needs the fast computational version for iteration, then experimental validation for final verification.

# Protein Design RL Training Loop (simplified demonstration)

def protein_design_rl_training(n_iterations=100, batch_size=8):

"""Main RL training loop for protein design."""

policy = PolicyNetwork(sequence_length=50)

structure_predictor = MockStructurePredictor() # Replace with ESMFold

target_coords = load_target_structure()

for iteration in range(n_iterations):

batch_rewards = []

for _ in range(batch_size):

# Step 1: Sample sequence from policy

sequence, log_probs = policy.sample_sequence()

# Step 2: Predict structure (ESMFold/AlphaFold)

predicted_coords = structure_predictor.predict_structure(sequence)

# Step 3: Calculate reward (TM-score)

reward = calculate_tm_score(predicted_coords, target_coords)

batch_rewards.append(reward)

# Step 4: Update policy using PPO

ppo_update(policy, log_probs, reward, baseline)

# Update baseline for variance reduction

baseline = 0.9 * baseline + 0.1 * np.mean(batch_rewards)

The Power of Molecular Context

Real proteins don't exist in isolation. They interact with other proteins, nucleic acids, ions, and ligands. Recent work on context-aware protein design showed that including molecular context during design dramatically improves results: "the overall structure median sequence recovery increased from 54% to 58% when an additional molecular context is provided."11

Results are even better for specific interactions: "recovery rates at protein interfaces improves significantly if small-molecule entities such as ions(67%), lipids(57%), ligands(61%) and glycans(50%) are included."12 The verification remains automated via AlphaFold, but the problem becomes richer and the solutions more biologically relevant.

This showcases a key advantage of biological benchmarks: they naturally increase in complexity. Start with monomer design, add protein-protein interfaces, include small molecules, model conformational dynamics. Each level builds on the previous, creating a natural curriculum for RL agents.

RNA Design: Millisecond Verification

RNA design offers even faster verification than proteins. "The ViennaRNA Package has been a widely used compilation of RNA secondary structure related computer programs for nearly two decades."13 Unlike AlphaFold's neural network predictions, ViennaRNA uses thermodynamic calculations: "Based on carefully measured thermodynamic parameters, exact dynamic programming algorithms can be used to compute ground states, base pairing probabilities, as well as thermodynamic properties."14

Result: sub-second verification of RNA designs.

The Eterna project built an entire game around this. "The community has grown to over 250,000 Eterna registered players as of 2018, with over 17,000 player-created puzzles."15 Players design RNA sequences to fold into target shapes, with immediate feedback from thermodynamic scoring. "The Eterna project has collected over 1 million player moves by crowdsourcing RNA designs."16

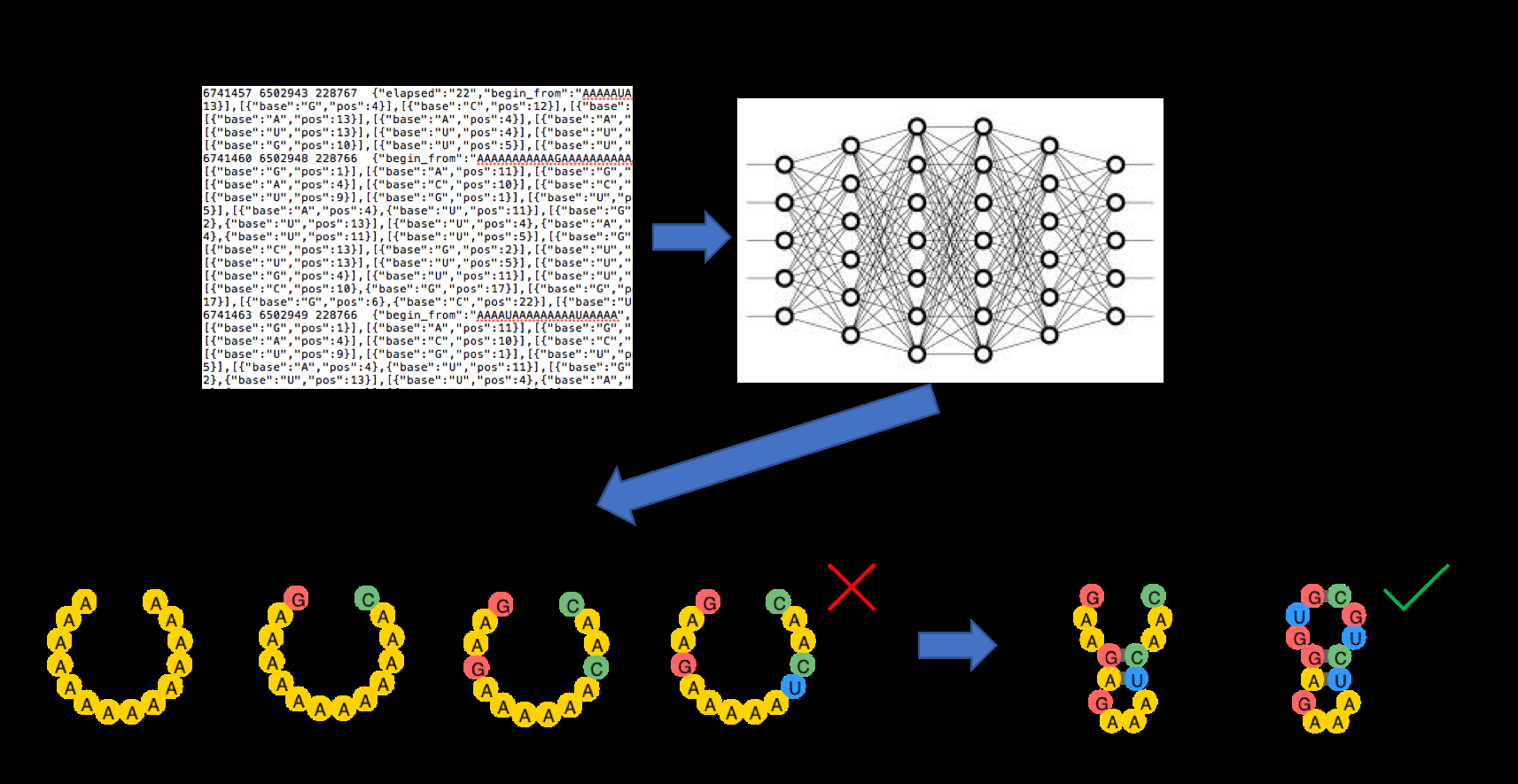

Figure 3: The EternaBrain reinforcement learning pipeline showing how player strategies were converted into training data for a CNN that learned to predict human design moves. Source: RNA inverse folding using Monte Carlo tree search

Figure 3: The EternaBrain reinforcement learning pipeline showing how player strategies were converted into training data for a CNN that learned to predict human design moves. Source: RNA inverse folding using Monte Carlo tree search

EternaBrain converted this crowdsourced data into RL training: "We present these data in the eternamoves repository and test their utility in training a multilayer convolutional neural network to predict moves."17 The model learns from successful human strategies, then improves through exploration.

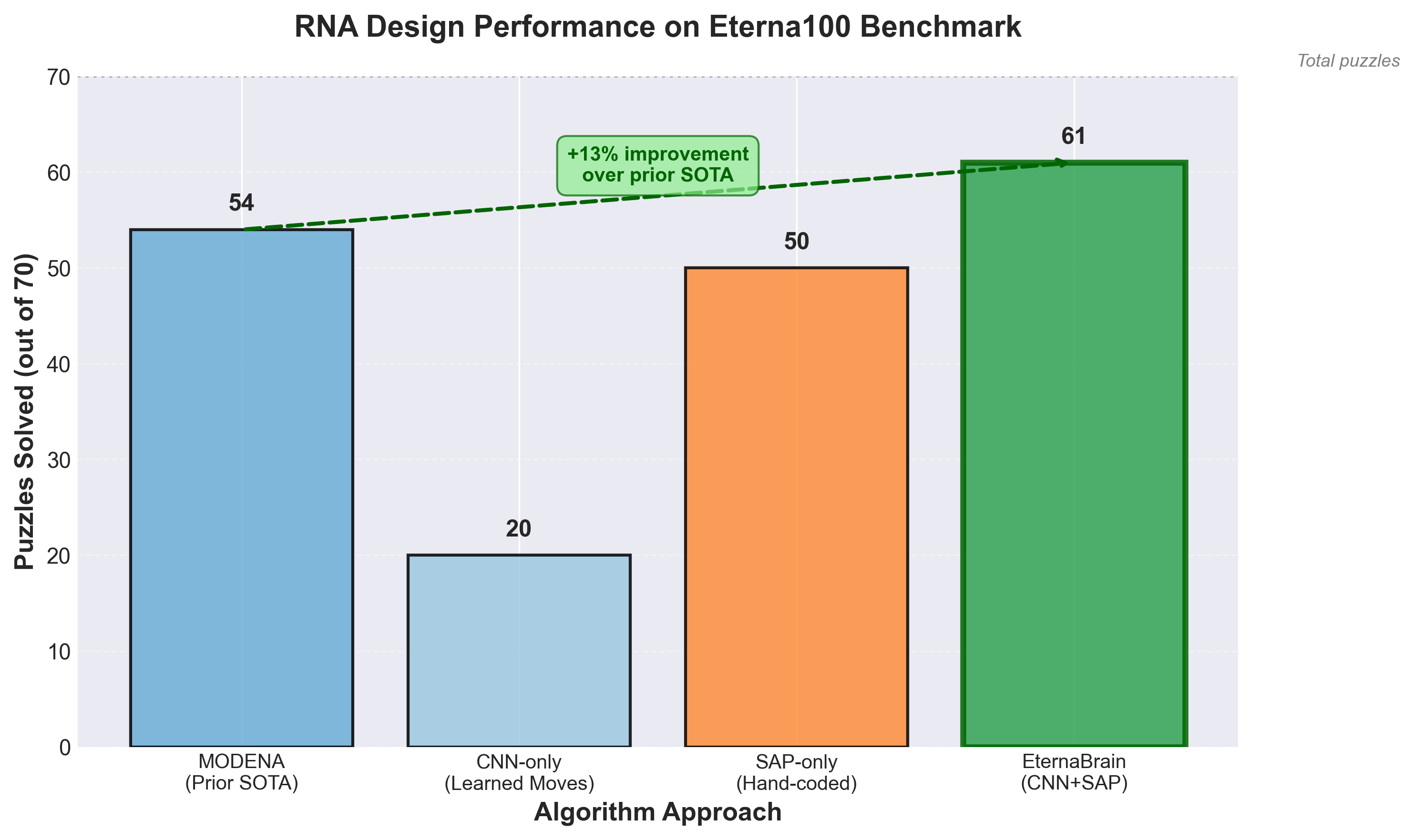

On the Eterna100 benchmark (100 difficult RNA design puzzles): "EternaBrain solved 61 of the 100 puzzles, surpassing the best prior algorithm MODENA by 7 puzzles."18 But the training process is what matters: "We started by training the model on all player data with 1.8 million moves spanning 12 representative puzzles from the Eterna progression dataset."19

1.8 million training examples, each verified in milliseconds. That's the scale RL needs.

The learning curve revealed important model limitations. "The model could not solve Simple Hairpin (the secondary structure designed by EternaBrain did not match the desired secondary structure), the easiest puzzle on the Eterna100."20 This drove architectural improvements combining learned predictions with strategic planning.

Performance breakdown: "Using EternaBrain's CNN-based moves alone solves only 20 puzzles on the Eterna100" while "Using the SAP alone (i.e., just hand-coded canonical player strategies) solves 50 puzzles on the Eterna100."21 The combination hits 61. This shows how RL training benefits from structured priors: you don't start from random initialization.

Figure 4: Performance comparison on Eterna100 benchmark showing how combining learned strategies (CNN) with hand-coded planning (SAP) yields the best results. Data from Wayment-Steele et al. (2021).

Figure 4: Performance comparison on Eterna100 benchmark showing how combining learned strategies (CNN) with hand-coded planning (SAP) yields the best results. Data from Wayment-Steele et al. (2021).

Molecular Docking: The Oracle Budget Game

Drug discovery introduces a new constraint: computational cost. While ViennaRNA runs in milliseconds and ESMFold in seconds, high-accuracy molecular docking takes minutes per molecule. This creates the "oracle budget" problem: you have a limited number of expensive evaluations to find optimal molecules.

"We docked 1.7 million ligands from the ChEMBL database against 15 AlphaFold proteins, giving us more than 25 million protein-ligand binding scores."22 The computational cost: "The computations were executed on a High-Performance Computing (HPC) cluster, taking approximately 45 days to complete and 600,000 CPU hours."23

That's fine for creating a training dataset, but not for online RL where each action needs immediate feedback. Solution: train a surrogate model on docking results, use the surrogate for RL training, periodically validate against the real docking simulator.

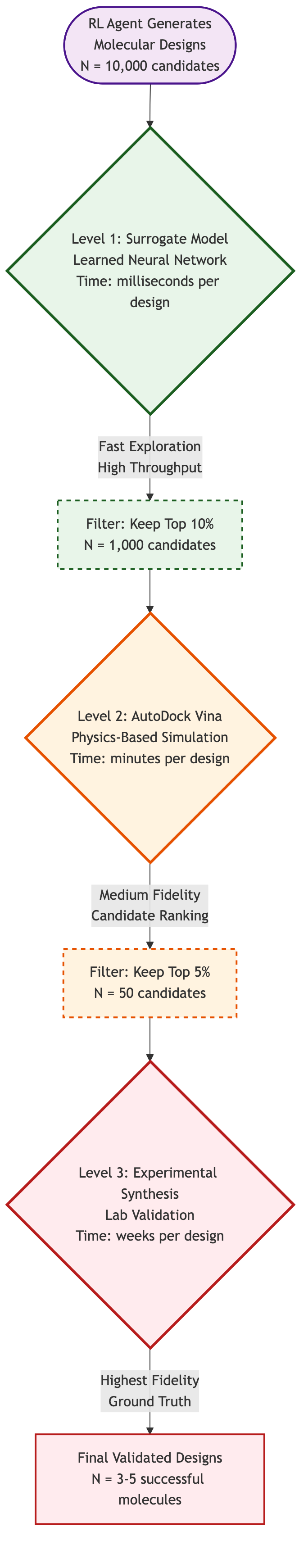

Figure 5: Multi-fidelity verification funnel for molecular design: from 10,000 candidates explored via surrogate models (milliseconds) to 50 ranked via physics simulation (minutes) to 3-5 validated experimentally (weeks). (Author's illustration)

Figure 5: Multi-fidelity verification funnel for molecular design: from 10,000 candidates explored via surrogate models (milliseconds) to 50 ranked via physics simulation (minutes) to 3-5 validated experimentally (weeks). (Author's illustration)

The PMO benchmark standardizes this: 10,000 oracle calls maximum per design task. Algorithms must balance exploration (trying diverse molecules) with exploitation (refining promising candidates) under this budget constraint. Machine learning models trained on the Smiles2Dock dataset achieved "highest R^2 score of 0.40 and the lowest RMSE of 2.89 for the configuration with 256 protein size, 512 ligand size."24 Good enough for training, validated against ground truth.

This mirrors real-world constraints. In actual drug discovery, you can only synthesize and test dozens or hundreds of candidates, not millions. The RL agent must learn sample-efficient search strategies.

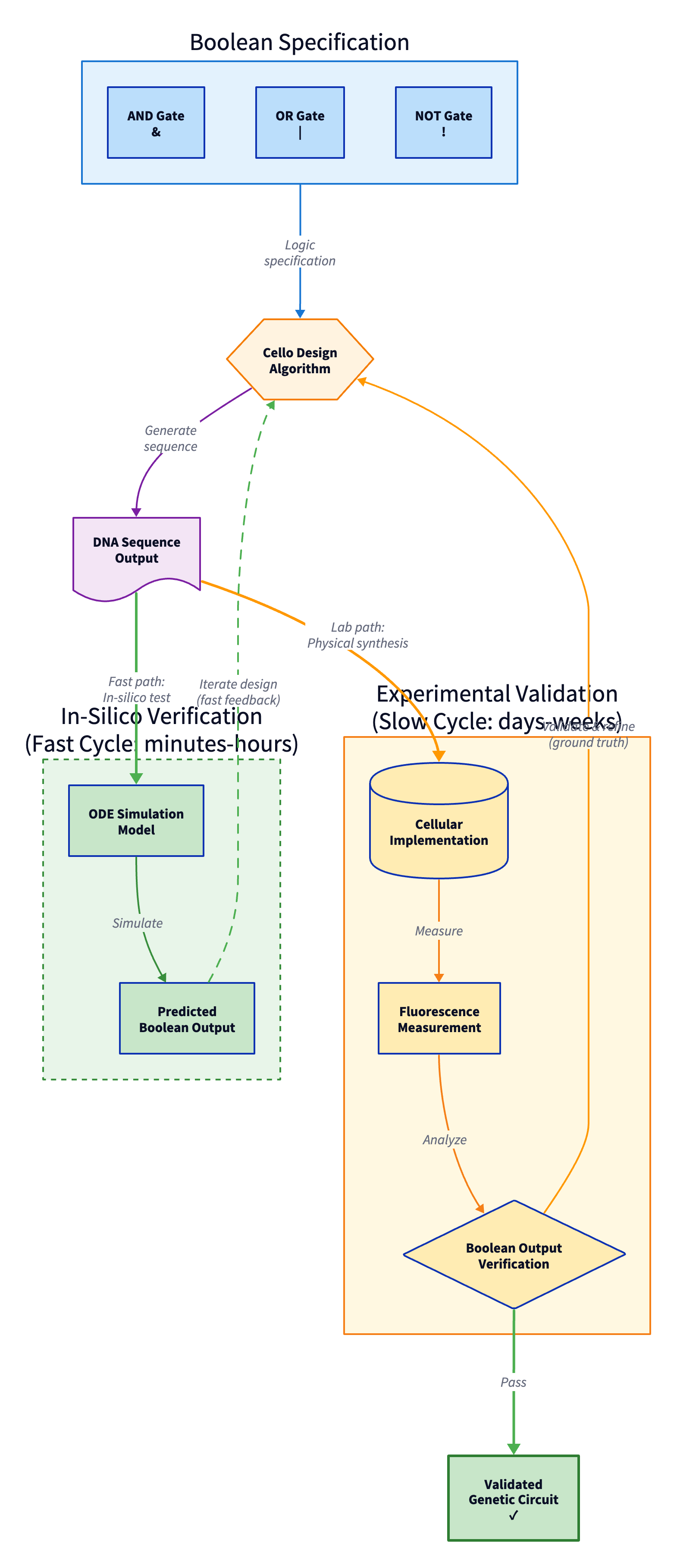

Genetic Circuits: Boolean Logic in Cells

Genetic circuit design pushes verification into experimental validation, but with structured constraints that enable semi-automated evaluation. The Cello genetic circuit design tool converts Boolean logic specifications into DNA sequences that implement those functions in cells.

Experimental validation shows approximately 71% of designed circuits function correctly in every output state.25 The verification requires actual biology: synthesize the DNA, insert into cells, measure fluorescence outputs under different input conditions. This takes days or weeks, making it impractical for RL training iterations.

But notice the structure: Boolean logic provides clear specifications. For a two-input AND gate, there are exactly 4 input combinations and 4 required outputs. Success is binary: either the circuit computes the correct function or it doesn't. No ambiguous evaluation.

Figure 6: Genetic circuit design workflow with dual verification paths: fast ODE simulation for training iterations (hours) and slow experimental validation for final confirmation (weeks). (Author's illustration)

Figure 6: Genetic circuit design workflow with dual verification paths: fast ODE simulation for training iterations (hours) and slow experimental validation for final confirmation (weeks). (Author's illustration)

The path to RL-ready benchmarks: simulate circuit behavior using ODE models of gene expression, train agents on simulated circuits, then experimentally validate the best designs. The simulation doesn't perfectly predict reality (hence the 71% success rate), but it's accurate enough to guide search.

Metabolic Pathway Design: Graph Search

Designing metabolic pathways (sequences of enzymatic reactions that convert starting materials into target molecules) frames as graph search. The graph nodes are molecules, edges are known enzymatic reactions. The task: find paths from available substrates to desired products.

The KEGG benchmark provides the chemical knowledge base. "Started with 19,119 KEGG compound entries (as of July 3, 2023)" and after careful curation ended with "After deduplication and quality control: 5,683 final metabolites."26 Current ML approaches achieve "Best Performance (XGBoost on Full Dataset): F1 Score: 0.8180" with "Matthews Correlation Coefficient (MCC): 0.7933"27 for predicting enzyme activity.

# Retrosynthesis Pathway Search with RL (simplified demonstration)

def beam_search_retrosynthesis(target_molecule, templates, starting_materials,

beam_width=5, max_depth=5):

"""RL-guided beam search for retrosynthesis pathways."""

value_function = ValueFunction() # Learned to estimate pathway quality

beam = [MoleculeState(target_molecule, depth=0, score=1.0)]

completed_pathways = []

while beam:

current_states = heapq.nsmallest(beam_width, beam)

beam = []

for state in current_states:

if state.smiles in starting_materials:

completed_pathways.append(reconstruct_pathway(state))

continue

for template in templates:

precursors = template.apply(state.smiles)

if precursors:

for precursor in precursors:

# Combine immediate reward with value estimate

reward = calculate_pathway_reward(precursor, template)

value = value_function.estimate_value(precursor)

new_score = state.score * (0.5 * reward + 0.5 * value)

heapq.heappush(beam, MoleculeState(precursor, new_score))

return sorted(completed_pathways, key=lambda x: x.score, reverse=True)

The feature engineering matters: "This approach generated 14,923 total features capturing chemical neighborhoods within molecules."28 Molecular fingerprints enable fast similarity searches and reaction predictions. One important finding: "metabolites with fewer than 7 non-hydrogen atoms showed unreliable classification."29 This becomes a curriculum decision for RL: train on larger molecules first, where verification is more reliable.

Practical Considerations for Bio-RL Benchmarks

Current biological benchmarks excel at static evaluation but often lack infrastructure for RL training. Here's what's needed:

Standardized Interfaces

Every benchmark needs a consistent API: state = env.reset(), next_state, reward, done = env.step(action). The OpenAI Gym pattern, but for biology. This exists for RNA (Eterna), partially for proteins (ProteinGym), barely for metabolic engineering or genetic circuits.

Reward Shaping

Raw scores (sequence recovery, folding accuracy, binding affinity) often provide sparse rewards: you only get signal when the full design succeeds. Intermediate rewards help: partial structure matches, reduced free energy, improved binding compared to baseline. "NequIP outperforms existing models with up to three orders of magnitude fewer training data"30 by using physically-informed representations that capture gradual improvement.

Computational Architecture

Three patterns dominate bio-RL training:

-

Synchronous verification: Generate designs one at a time, verify each before the next. Simple but slow. Only viable with sub-100ms verification latency (ViennaRNA).

-

Asynchronous batch verification: Generate batches of candidates, dispatch to verification workers, collect results as they complete. Scales to hundreds of designs per batch.

-

Learned surrogate models: Train neural networks to approximate expensive verification. Use surrogate for exploration, periodically validate with true physics. Orders of magnitude faster but introduces approximation error.

Figure 7: Verification speeds across biological domains span 6 orders of magnitude, determining which verification tier each method enables for RL training. (Author's compilation from ViennaRNA, ESMFold, AlphaFold2, and AutoDock documentation)

Figure 7: Verification speeds across biological domains span 6 orders of magnitude, determining which verification tier each method enables for RL training. (Author's compilation from ViennaRNA, ESMFold, AlphaFold2, and AutoDock documentation)

Statistical Rigor

"Inadequate statistical rigor can lead to misleading conclusions."31 Biological simulations have stochasticity (Brownian dynamics, random seeds), temperature effects (thermodynamic calculations), and parameter sensitivity. Report all parameters, average across multiple seeds, and provide uncertainty estimates. "Optimization claims from Chapter 10 require validation on representative tasks."32

The Agentic AI Challenge

BixBench revealed a critical gap in current AI systems: "Agentic AI systems are designed to operate with a high degree of autonomy, allowing them to independently perform tasks such as hypothesis generation, literature review, experimental design, and data analysis."33 Performance varies dramatically by task phase.

"Agent Laboratory demonstrated high success rates in data preparation, experimentation, and report writing. However, its performance dropped significantly in the literature review phase."34 Why? Literature review lacks automated verification: there's no referee to say "your summary is 85% accurate" or "you missed these three key papers." Contrast with experimental design: run the experiment, measure outcomes, compute success metrics.

Figure 8: BixBench evaluation showing frontier model performance on biological data analysis tasks. Both GPT-4o and Claude 3.5 Sonnet achieve low accuracy (15-21%) on open-ended scientific analysis. Source: BixBench: A Comprehensive Benchmark for Agentic AI in Bioinformatics

Figure 8: BixBench evaluation showing frontier model performance on biological data analysis tasks. Both GPT-4o and Claude 3.5 Sonnet achieve low accuracy (15-21%) on open-ended scientific analysis. Source: BixBench: A Comprehensive Benchmark for Agentic AI in Bioinformatics

The highest-impact biological RL benchmarks will support complete scientific workflows: design molecules, predict properties, suggest synthesis routes, plan experiments, interpret results. Each step needs verification; many steps can be automated. "Questions about system reliability, reproducibility, and ethical governance continue to pose significant hurdles."35 Automated verification helps with the first two: if every intermediate step has clear success criteria, you can track where errors emerge.

Future Directions

Three directions show particular promise:

Dynamic Structural Biology: AlphaFold models static structures, but proteins flex and breathe. AlphaFLOW "substantially surpasses the MSA baselines in the prediction of conformational flexibility, distributional modeling of atomic positions, and replication of higher-order ensemble observables."36 The RL task: design sequences that not only fold correctly but exhibit specific dynamic behavior: controlled flexibility, allosteric regulation, conformational switching.

Multi-Objective Optimization: Real biological design requires balancing multiple objectives. A protein must fold, bind specific targets, avoid binding off-targets, remain stable at body temperature, and resist aggregation. Single-objective benchmarks miss these trade-offs. Imagine RL agents learning Pareto frontier discovery: finding the set of non-dominated designs that represent optimal trade-offs across objectives.

Experimental-in-the-Loop RL: The ultimate benchmark: close the loop between computation and lab experiments. Design candidates computationally, select the most promising via RL, synthesize and test experimentally, feed results back to update the model. Validation from protein design research: "All 4 designed mutants displayed thermal denaturation profiles indicative of much higher stability (Tm ~80C or higher vs. ~42C for wild-type TEM-1)."37 Computational predictions translated to enhanced real-world properties.

Conclusion

Biology provides what RL needs most: verifiable inverse problems at scale. Not every challenge has a perfect automated referee (experimental validation remains essential), but computational verification enables the millions of training iterations that RL demands.

The benchmarks exist: protein inverse folding with AlphaFold verification, RNA design with ViennaRNA thermodynamics, molecular docking with AutoDock scoring, metabolic pathway design with reaction feasibility models. What's needed is RL infrastructure: standardized APIs, reward shaping, difficulty curricula, multi-fidelity verification.

"While significant progress has been made in developing systems for automating certain aspects of the scientific research process, the ultimate realization of fully automated scientific systems remains elusive."38 Biological RL benchmarks move us closer by providing the intermediate layer: not fully automated science, but automated verification of specific design tasks.

The path forward: convert evaluation benchmarks into training environments, standardize verification interfaces, build curricula from simple to complex challenges, and close the loop between computation and experiment. Biology's physical laws give us the referees. RL gives us the training paradigm. Together, they enable agents that don't just answer questions: they design solutions.

References

Footnotes

-

Jimenez et al., "SWE-bench: Can Language Models Resolve Real-World GitHub Issues?" (2024). ↩

-

Lorenz et al., "ViennaRNA Package 2.0," Algorithms for Molecular Biology (2011). ↩

-

Kaur et al., "BixBench: A Benchmark for Evaluating Agentic AI on Real-World Bioinformatics Tasks" (2024). ↩

-

SWE-bench methodology. ↩

-

Best Practices for Machine Learning Benchmarking (2024). ↩

-

Watson et al., "De novo protein design using AF2-design" (2023). ↩

-

Dauparas et al., "ProteinMPNN: Robust deep learning based protein sequence design" (2022). ↩

-

Tan et al., "ProteinInvBench: Benchmarking Protein Inverse Folding" (2024). ↩

-

Lin et al., "Evolutionary-scale prediction of atomic level protein structure with a language model" (2022). ↩

-

Watson et al., "De novo protein design using AF2-design" (2023). ↩

-

Harteveld et al., "Context-aware geometric deep learning for protein sequence design" (2023). ↩

-

Harteveld et al., "Context-aware geometric deep learning for protein sequence design" (2023). ↩

-

Lorenz et al., "ViennaRNA Package 2.0," Algorithms for Molecular Biology (2011). ↩

-

Lorenz et al., "ViennaRNA Package 2.0," Algorithms for Molecular Biology (2011). ↩

-

Wayment-Steele et al., "RNA inverse folding using Monte Carlo tree search" (2021). ↩

-

Wayment-Steele et al. (2021). ↩

-

Wayment-Steele et al. (2021). ↩

-

Wayment-Steele et al. (2021). ↩

-

Wayment-Steele et al. (2021). ↩

-

Wayment-Steele et al. (2021). ↩

-

Wayment-Steele et al. (2021). ↩

-

Sadybekov et al., "Smiles2Dock: Large-scale Protein-Ligand Docking Dataset" (2024). ↩

-

Sadybekov et al. (2024). ↩

-

Sadybekov et al. (2024). ↩

-

Nielsen et al., "Genetic circuit design automation," Science (2016). ↩

-

KEGG Compound Classification Dataset Analysis (2023). ↩

-

KEGG study (2023). ↩

-

KEGG study (2023). ↩

-

KEGG study (2023). ↩

-

Batzner et al., "E(3)-equivariant graph neural networks for data-efficient and accurate interatomic potentials" (2022). ↩

-

Best Practices for Machine Learning Benchmarking (2024). ↩

-

Best Practices for Machine Learning Benchmarking (2024). ↩

-

Zhang et al., "A Survey of Agentic AI Systems for Scientific Discovery" (2025). ↩

-

Zhang et al. (2025). ↩

-

Zhang et al. (2025). ↩

-

Jing et al., "AlphaFLOW: Protein Ensemble Generation with Flow Matching" (2024). ↩

-

Harteveld et al., "Context-aware geometric deep learning for protein sequence design" (2023). ↩

-

Zhang et al., "A Survey of Agentic AI Systems for Scientific Discovery" (2025). ↩