Biological World Models: The Projects You're Not Building (But Should Be)

Picture a bacterium swimming toward a glucose gradient. It has no eyes, no brain, no neurons. Yet somehow it predicts: "If I keep moving this direction, I'll find more food." It maintains an internal model of its environment, comparing past concentration to present, approximating a derivative. It has a world model.

Now ask yourself: what would it take to build that in code?

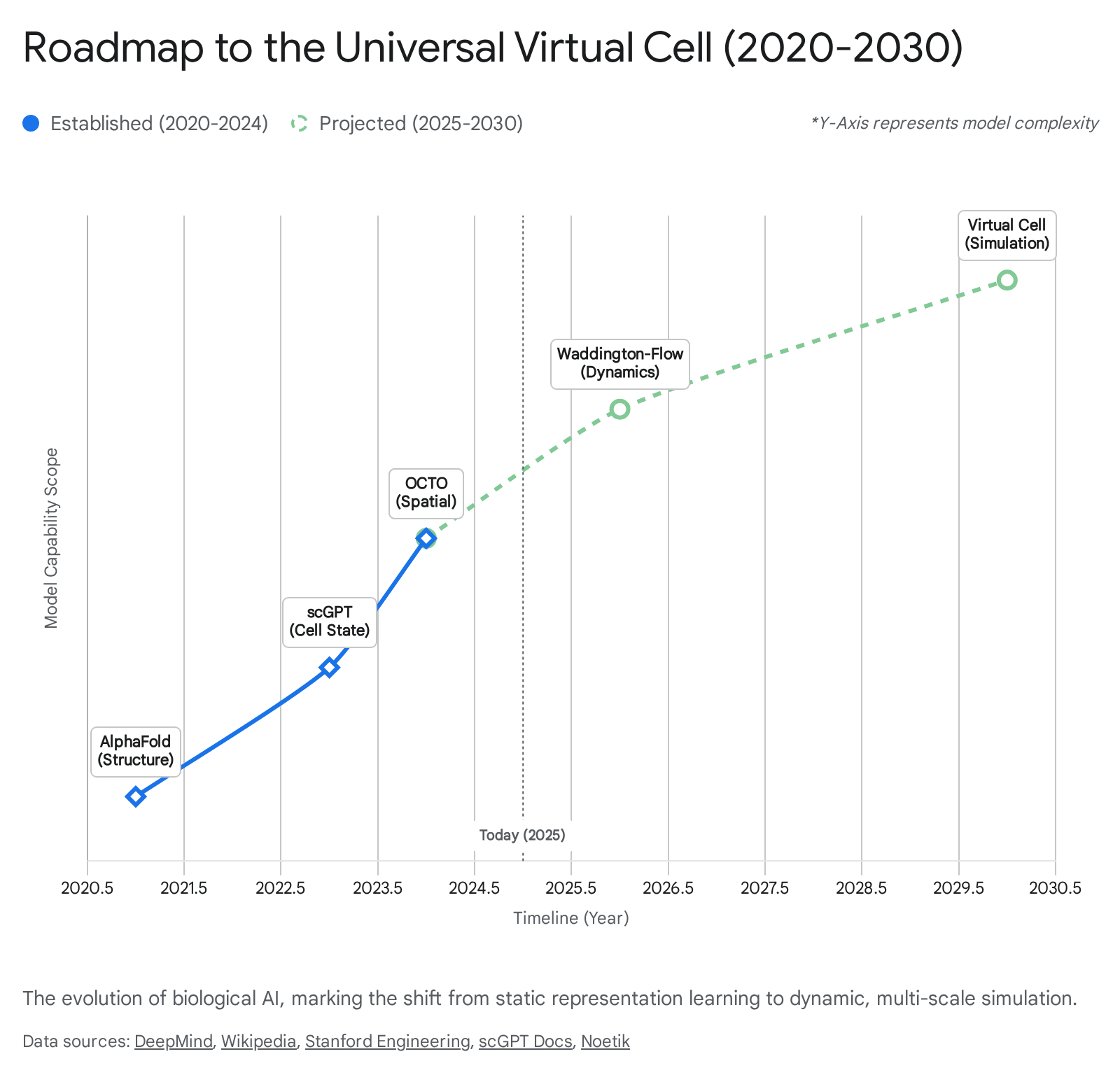

This question sits at the heart of an emerging shift in computational biology. We spent 2020-2024 learning to represent biological entities as high-dimensional vectors. The next five years will be different. We will learn to simulate biological processes.

Here's the uncomfortable truth that most of us are missing: foundation models like scGPT and Geneformer are sophisticated pattern recognizers, not biological reasoning engines. They learn static representations. They don't simulate. They don't answer "what if?"

That distinction matters more than you think.

Figure 1: The hierarchy of biological intelligence, showing the progression from raw data through foundation models to world models capable of simulation. Source: The In-Silico Cell: Architecting World Models for Biological Systems

Figure 1: The hierarchy of biological intelligence, showing the progression from raw data through foundation models to world models capable of simulation. Source: The In-Silico Cell: Architecting World Models for Biological Systems

The Difference That Actually Matters

Let's be precise about what we're talking about.

"A Foundation Model, such as scGPT or ESM, is primarily a representation learner. Trained on vast corpora of data (e.g., 33 million single-cell transcriptomes or billions of protein sequences), its objective is to learn a high-dimensional embedding space where biologically similar entities are distinct." That's impressive. scGPT trained on over 33 million human cells can learn the manifold of biologically plausible cell states. Geneformer pushes further with 104 million human single-cell transcriptomes.

Foundation models answer: What is this?

"A World Model, by contrast, is a simulator of dynamics and causality. It uses the representations learned by foundation models to answer 'What if?' questions."

World models answer: What happens next?

Here's the concrete difference. scGPT can look at a cell's expression profile and tell you it's probably a T cell. That's classification, powerful and useful. A world model takes that same cell and asks: "If I knock out gene X, what happens in 48 hours?" Then it rolls out a trajectory.

"A world model does not just predict a label; it rolls out a trajectory. It simulates how a stem cell differentiates into a neuron over time, how a tumor responds to immunotherapy, or how a gene network reconfigures after a knockout."

The perturbation prediction problem exposes the limitation. When you knock out Gene X, you're not asking "what embedding should this cell have?" You're asking "what trajectory will this cell follow?" That's a dynamics question, not a representation question.

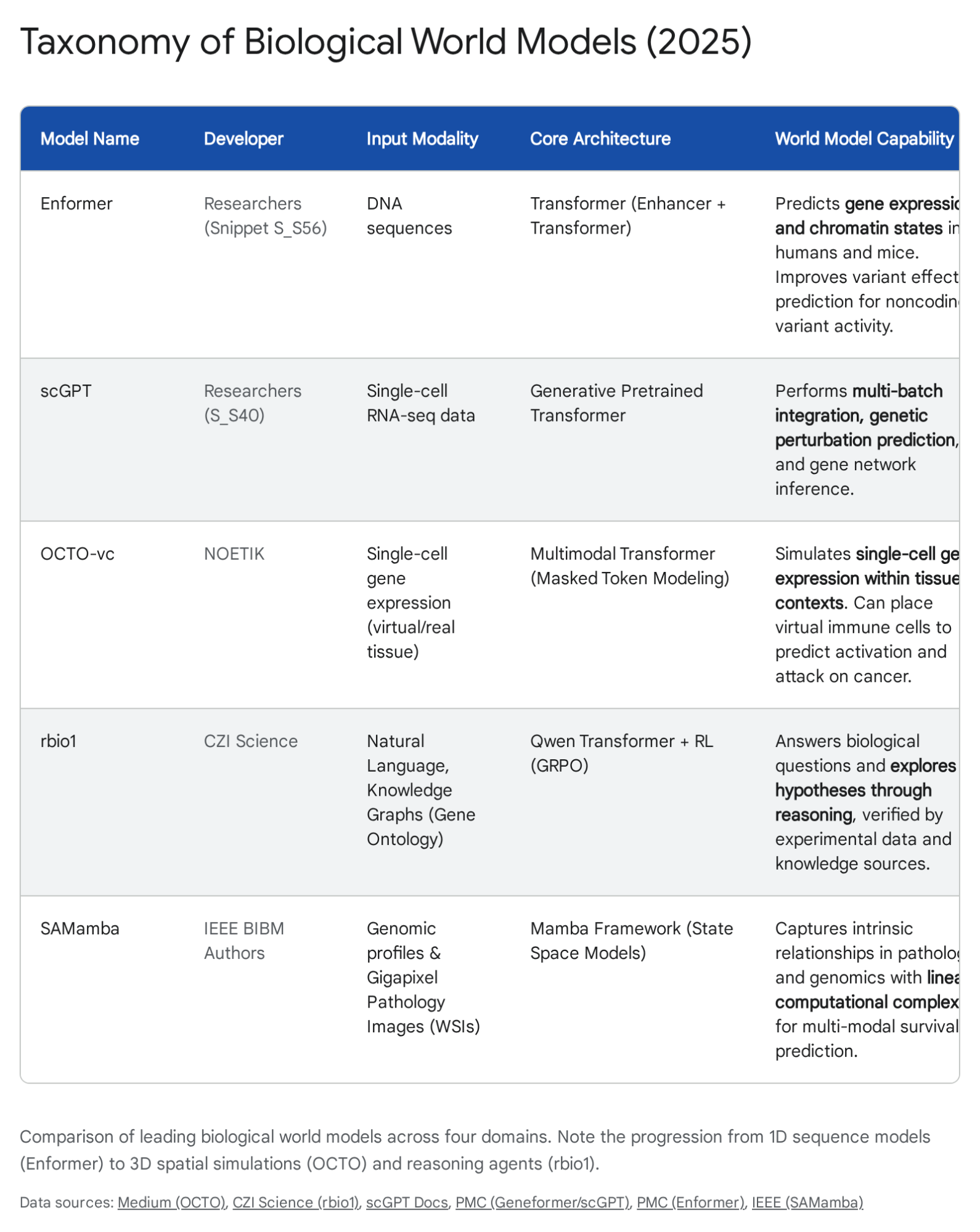

Figure 2: Current taxonomy of biological world models, comparing input modalities, architectures, and capabilities. Source: The In-Silico Cell: Architecting World Models for Biological Systems

Figure 2: Current taxonomy of biological world models, comparing input modalities, architectures, and capabilities. Source: The In-Silico Cell: Architecting World Models for Biological Systems

Why Foundation Models Aren't Enough

Let me be blunt about where foundation models fall short.

A recent benchmarking study produced a sobering finding: "Foundation models (scGPT, scFoundation) did not outperform simple baselines in this benchmark. Simple mean-of-training-example models showed competitive performance." Read that again. Taking the mean of training examples, the most naive possible baseline, matches or beats state-of-the-art foundation models on perturbation prediction.

This isn't a failure of engineering. It's a failure of approach. Foundation models optimize for representation quality. They don't optimize for causal prediction.

The Case for Building Smaller

Here's the contrarian position: you don't need 128 H100 GPUs to build useful biological world models.

Yes, "Training models like OCTO (20 billion tokens) requires massive compute infrastructure (128+ H100 GPUs). The 'Universal Virtual Cell' will likely require exascale computing, limiting its development to well-funded consortia or tech giants." But between your laptop and an exascale cluster exists a vast middle ground that's being completely ignored.

Consider the OCTO robot model. It provides "pretrained Octo model checkpoints with 27M and 93M parameters." That's 27 million parameters, not 27 billion. "A finetuning run of the same model on a single NVIDIA A5000 GPU with 24GB of VRAM takes approximately 5 hours and can be sped up with multi-GPU training." A single A5000. Five hours. This is not exascale computing.

The biology community has convinced itself that meaningful models require massive scale. The robotics community proved otherwise. "On average Octo had a 29% higher success rate than RT-1-X (35M parameters)" and when "compared to RT-2-X (55 billion parameters)... Octo performed similarly." A 93M parameter model matching a 55B parameter model. Scale is not destiny.

Three Project Ideas You Can Actually Build

Let me be specific. Here are three feasible world model projects that a small team with university-level compute can implement. These aren't toy problems. They address real biological questions.

Project 1: The Perturbation Response Predictor (Beginner)

The Problem: You have Perturb-seq data showing transcriptional responses to CRISPR knockouts. You want to predict responses to unseen perturbations.

Why It's Tractable: "scGPT can be fine-tuned on the Norman dataset to predict the shift in a cell's transcriptional state after a gene knockout. It effectively hallucinates the post-perturbation state." The data exists. The baselines are established. The benchmark reveals that current methods underperform, which means there's room for improvement.

The Novel Angle: Don't try to predict the final state directly. Model the perturbation as a learned transformation in latent space using flow matching.

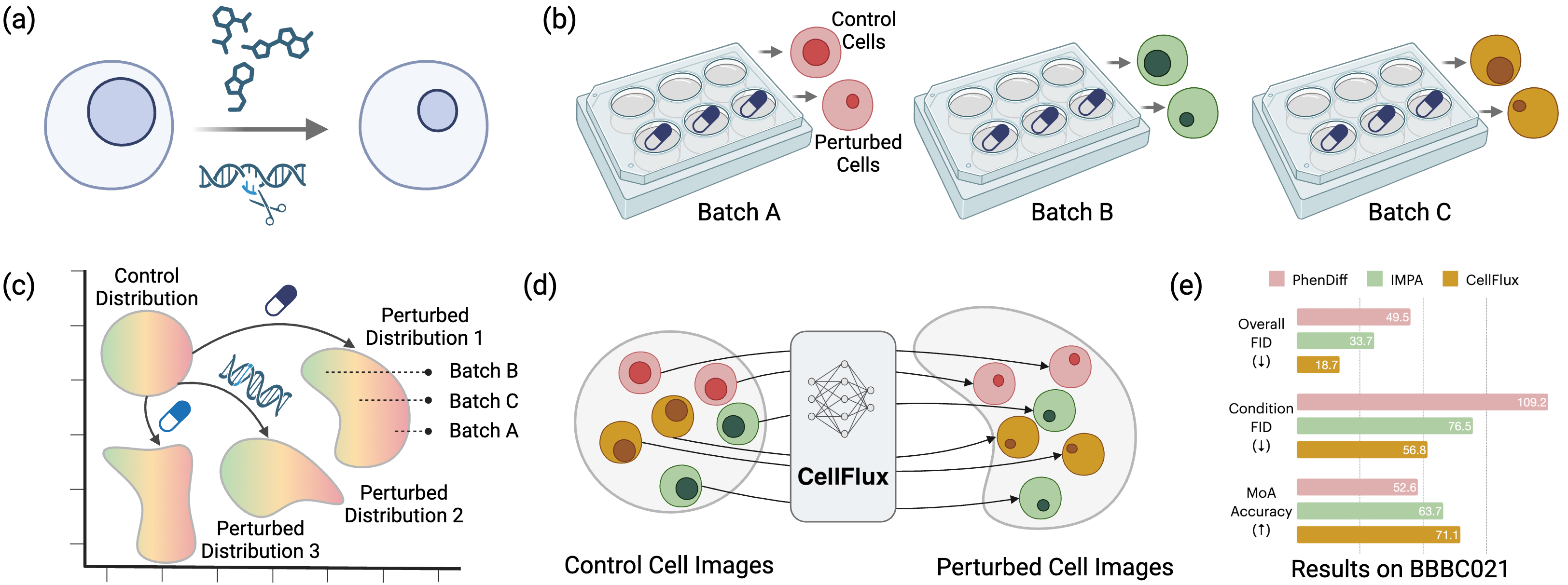

CellFlux demonstrates this approach for morphology: "CellFlux generates biologically meaningful cell images that faithfully capture perturbation-specific morphological changes, achieving a 35% improvement in FID scores and a 12% increase in mode-of-action prediction accuracy over existing methods."

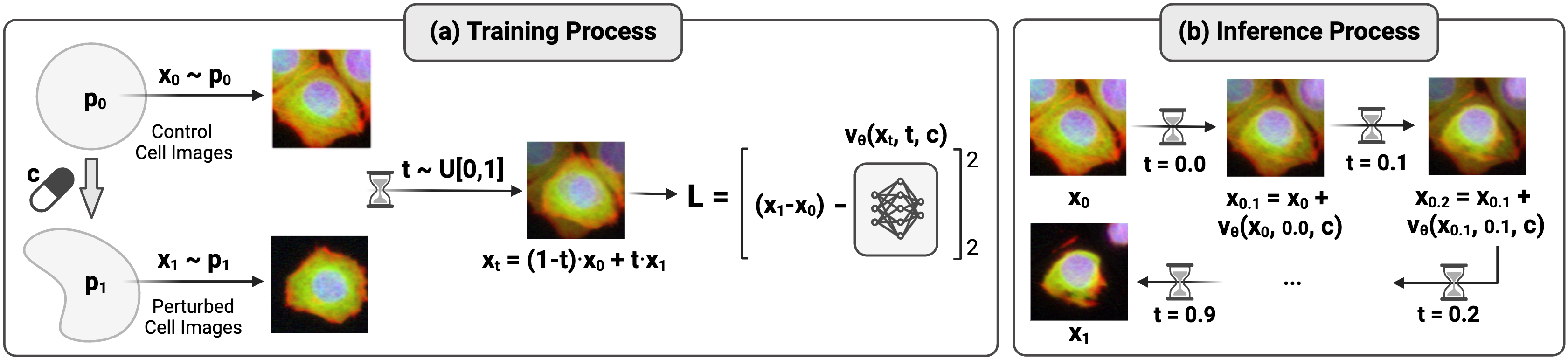

Figure 3: CellFlux framework for simulating cellular morphology changes via flow matching. Source: CellFlux team, arXiv:2502.09775, 2025

Figure 3: CellFlux framework for simulating cellular morphology changes via flow matching. Source: CellFlux team, arXiv:2502.09775, 2025

The key insight is "formulating cellular morphology prediction as a distribution-to-distribution learning problem, and leveraging flow matching... to solve this problem." Translate this to transcriptomics. Instead of predicting the perturbed expression profile directly, learn a velocity field that transforms the control distribution into the perturbed distribution.

"Flow matching provides a framework to learn transformations between probability distributions by constructing smooth paths between paired samples. It models how a source distribution continuously deforms into a target distribution through time."

The mathematical machinery is clean. "The transformation process follows an ordinary differential equation: dx_t = v_theta(x_t, t)dt." You're learning a function that pushes cells from one state to another. That's causally interpretable.

Compute Requirements: CellFlux reports "Training is conducted for 100 epochs on 4 A100 GPUs." Transcriptomic data is lower dimensional than images, so your requirements will be lower.

How to Get Started: Use the Norman dataset or scPerturb database. Start with Geneformer or scGPT embeddings as features. Train a simple MLP to predict post-perturbation embeddings, then upgrade to flow matching once you have the baseline working.

Project 2: The Metabolic Dynamics Simulator (Intermediate)

The Problem: You've engineered E. coli strains for metabolite production. You want to predict which genetic configurations produce the highest yields over time.

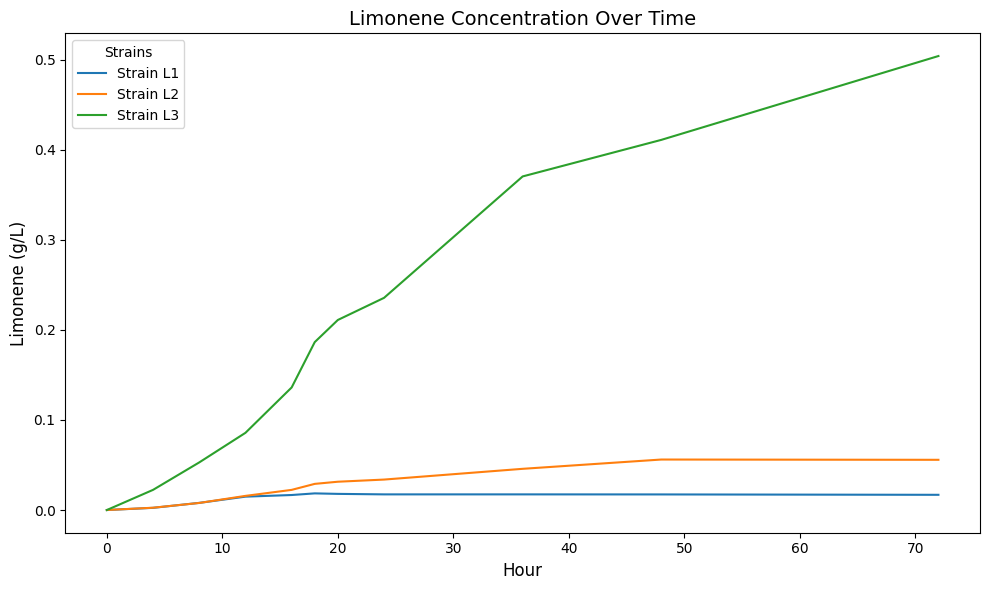

Why It's Tractable: Neural ODEs have already solved this problem at research scale with dramatic results.

"Our results show a greater than 90% improvement in root mean squared error over baselines across both Limonene (up to 94.38% improvement) and Isopentenol (up to 97.65% improvement) pathway datasets." That's not a marginal improvement. That's a step change.

The speed gains are equally striking: "The NODE models demonstrated a 1000x acceleration in inference time." Once trained, predictions take milliseconds.

Figure 4: Neural ODE prediction of limonene production dynamics across engineered E. coli strains, demonstrating accurate trajectory forecasting. Source: arXiv:2512.08732

Figure 4: Neural ODE prediction of limonene production dynamics across engineered E. coli strains, demonstrating accurate trajectory forecasting. Source: arXiv:2512.08732

The Approach: Neural ODEs learn continuous dynamics directly. "Using a NODE, the step of approximating derivatives and subsequently fitting an ML model for each feature can be circumvented entirely. Instead, a fully connected neural network is trained to learn the derivative of each state and control variable directly."

The biological inductive bias matters. "A physiology-informed regularization term (PIR) is added to the loss function which penalizes predictions of negative values for metabolite concentrations." Metabolite concentrations can't be negative. Encoding this constraint improves model quality and interpretability.

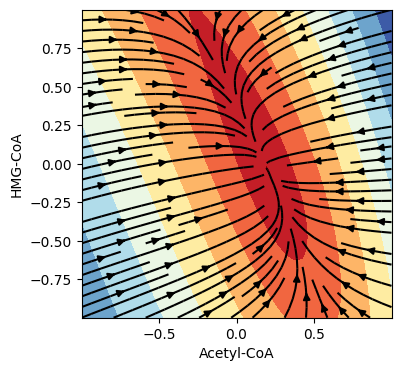

"The neural network is tasked with learning the vector field that evolves a given time point through a trajectory that best approximates the dynamics represented in the training data." The learned vector field is itself scientifically interesting. It represents the model's understanding of how metabolic state evolves.

Figure 5: Learned vector field from Neural ODE model showing metabolic flow in phase space. Arrows indicate direction and magnitude of flux. Source: arXiv:2512.08732

Figure 5: Learned vector field from Neural ODE model showing metabolic flow in phase space. Arrows indicate direction and magnitude of flux. Source: arXiv:2512.08732

Compute Requirements: "Training time for baseline models was 52.08-61.79 minutes while NODE training took only 5.40-5.61 minutes. Inference time dropped from 4.04-4.83 minutes to 0.004 minutes." Less than six minutes to train. You can iterate rapidly on a single GPU.

How to Get Started: Use torchdiffeq or Diffrax (JAX). "The 8th order Dormand-Prince method is used from the torchdiffeq library." Start with metabolic time-series data. "The original dataset contains 91 metabolomic and 23 proteomic features, each recorded over 72 hours in 14 intervals." The architecture is compact: "The architecture of the NODE Function consists of: Input 23, multiple Linear layers with hidden size 10, Tanh activations, and Output 23."

Project 3: The Cell Fate Trajectory Engine (Advanced)

The Problem: Given a cell's current transcriptional state, predict its fate probability across multiple terminal states.

Why It's Tractable: "The aim of the CellRank algorithm is to detect the initial, intermediate and terminal states of a system, and to define a global fate map that assigns, for each cell, the probability of reaching each terminal state." CellRank 2 provides the framework for fate assignment. The missing piece is a generative model that can simulate trajectories forward.

The Novel Angle: "Algorithms like CellRank 2 or RNA Velocity can provide the 'velocity vectors' needed to train the flow matching network." RNA velocity gives you directional information about where cells are headed. Use this to supervise a trajectory model.

Figure 6: The Waddington-Flow Engine concept: DNA sequence shapes the epigenetic potential energy surface, determining cell fate trajectories. Mutations warp the surface, altering which valleys cells flow into. Source: The In-Silico Cell: Architecting World Models for Biological Systems

Figure 6: The Waddington-Flow Engine concept: DNA sequence shapes the epigenetic potential energy surface, determining cell fate trajectories. Mutations warp the surface, altering which valleys cells flow into. Source: The In-Silico Cell: Architecting World Models for Biological Systems

The Waddington metaphor is more than a metaphor. "The Core Engine uses a Neural Differential Equation (Neural ODE) or Flow Matching network. The model does not predict the next state directly. Instead, it learns the Vector Field V(x, t) that governs the flow of the cell state x."

The architecture would combine:

- A Mamba encoder for long-range genomic context (because "Mamba utilizes a selective state space mechanism... It achieves linear scaling (O(N)) with sequence length")

- A flow matching decoder that learns the differentiation vector field

- Conditioning on perturbation embeddings for "what if?" prediction

The Key Constraint: "In omics, measuring a cell typically destroys it. We rarely see the same cell at two different time points. Most data is 'snapshot' data, static observations of different cells at different stages." You need to learn dynamics from snapshots, which is exactly what optimal transport and flow matching were designed for.

CellOT shows the way: it "uses input convex neural architectures for interpretable transport maps. It handles unpaired before/after perturbation data naturally."

The Honest Limitations

Let me be honest about what we haven't figured out yet.

Data remains the bottleneck. "NODEs, much like other ML methods, rely heavily on the quantity and quality of the data, necessitating the interpolation techniques implemented." If your time-series metabolomics has 14 timepoints over 72 hours, you're working with sparse supervision. Interpolation helps, but it's not a substitute for denser measurements.

Uncertainty quantification is unsolved. "World models must not just output a prediction; they must output a confidence interval. Bayesian Neural Networks or Ensemble methods are critical here." A model that predicts metabolite yield without confidence bounds is less useful than one that says "yield will be 0.5 g/L plus or minus 0.2 g/L." Building calibrated uncertainty into Neural ODEs and flow matching is active research.

The sim-to-real gap is real. Models trained on in vitro data may not transfer to in vivo biology. Models trained on cell lines may not transfer to primary cells. Every generalization claim needs experimental validation.

The measurement problem compounds everything. "Cell painting requires cell fixation, which is destructive, making it impossible to observe the same cells dynamically during a perturbation. This creates a fundamental constraint: we cannot obtain paired samples showing the exact same cell without and with treatment." This is why biology differs from robotics, where continuous video provides ground truth trajectories.

Figure 7: Flow matching approach: training learns the velocity field from interpolated samples; inference applies it iteratively to transform cell states. Source: CellFlux team, arXiv:2502.09775, 2025

Figure 7: Flow matching approach: training learns the velocity field from interpolated samples; inference applies it iteratively to transform cell states. Source: CellFlux team, arXiv:2502.09775, 2025

Getting Started Tomorrow

If you want to build a biological world model, here's a concrete path forward.

Week 1-2: Set up infrastructure

- Install JAX and Equinox. "JAX is a functional Python library for numerical computing and machine learning. Equinox layers PyTorch-like neural network syntax atop JAX for scientific computing with full composability." JAX's autodiff integrates cleanly with ODE solvers through Diffrax.

- Pull in scanpy and scvi-tools for single-cell data handling. "scvi-tools is a package for probabilistic modeling and analysis of single-cell omics data... It implements scVI, scANVI, totalVI, and other models for integration, denoising, and analysis."

- Download one dataset: Norman perturbation data or BBBC021 images.

Week 3-4: Implement a baseline

- Start with the simplest thing that could work. For perturbation response, that might be training a VAE on your control cells and learning a perturbation-conditioned latent shift.

- Compare against the baselines from the Nature Methods benchmark. If you can beat the mean-of-training-examples, you're doing something right.

Month 2: Add dynamics

- Replace your static predictor with a flow matching model. The CellFlux training procedure is straightforward: "We employ the rectified flow formulation, which yields a simple straight-line path... This linear path has a constant velocity field."

- "We incorporate classifier-free guidance to improve generation fidelity. During training, we randomly mask conditions with probability p_c, replacing c with a null token." This is just dropout on your conditioning, and it significantly improves conditional generation.

- Use a U-Net for the velocity predictor. "The velocity field v_theta is realized through a U-Net architecture."

Month 3: Validate biologically

- "CellFlux achieves 71.1% MoA accuracy, closely matching real images (72.4%) and significantly surpassing other methods (best: 63.7%)." Mode-of-action prediction is a good biological sanity check. If your model can distinguish drug mechanisms, it's learned something real.

- For trajectory models, compare predicted fate probabilities against CellRank. For metabolic models, compare predicted yields against experimental measurements.

- Remember: "For metabolic engineering purposes the ability to reliably identify the most productive strain is sufficient." You don't need perfect accuracy to be useful.

Figure 8: The roadmap to the Universal Virtual Cell, showing progression from structure prediction through dynamics to full simulation. Source: The In-Silico Cell: Architecting World Models for Biological Systems

Figure 8: The roadmap to the Universal Virtual Cell, showing progression from structure prediction through dynamics to full simulation. Source: The In-Silico Cell: Architecting World Models for Biological Systems

Why These Projects Matter

I've deliberately chosen projects that fall between "toy example" and "Universal Virtual Cell." Here's why this middle ground is important.

First, it's where the science happens. You don't need a perfect simulation of cellular physics. You need a model accurate enough to guide experimental decisions. The 90% improvement in prediction accuracy achieved by Neural ODEs isn't theoretically elegant. It's practically useful.

Second, it's where the insights emerge. "Even when the error between the NODE prediction and actual time series is large, the model appears to qualitatively capture the underlying dynamics, missing only the scale factor." A model that captures dynamics but gets scale wrong is still scientifically valuable. It tells you something about mechanism.

Third, it's achievable with realistic resources. The historical timeline tells a clear story: "2020-2024: The era of Foundation Models (scGPT, ESM). We successfully learned to represent biological entities as high-dimensional vectors. 2025-2030: The era of World Models. We will learn to simulate biological processes."

We're in the early phase of this transition. The field is wide open.

The Bigger Picture

"The ultimate goal is the Universal Virtual Cell (UVC): a differentiable, multi-scale simulation of cellular life that is indistinguishable from wet-lab reality." That's a decade-plus vision requiring massive coordinated investment.

"Building a virtual cell that simulates cellular behaviors in silico has been a longstanding dream in computational biology." "Such a system would revolutionize drug discovery by rapidly predicting how cells respond to new compounds or genetic modifications, significantly reducing the cost and time of biomedical research."

But between here and there lies an enormous amount of scientifically useful work. Models that predict perturbation responses. Models that simulate metabolic dynamics. Models that forecast cell fate. Each of these is achievable with today's methods and moderate resources.

"We are standing at the threshold of a new era in the life sciences. The 'Biological World Model' is evolving from a theoretical construct into a concrete engineering discipline."

Remember the bacterium?

It maintains a temporal comparison: past concentration versus present. It approximates a derivative. It has a world model.

Your models don't need to be universal. They don't need to simulate entire organisms. Start with one perturbation type, one cell line, one pathway. The remarkable thing about this moment is that we have the technical ingredients. Flow matching works. Neural ODEs scale. Foundation models provide useful initializations. The missing piece is execution.

The field has been waiting for someone else to build these models. The large consortia have the compute but move slowly. The foundation model labs optimize for benchmarks, not biological insight. Academic groups have the domain expertise but often lack the ML engineering depth.

If you're reading this, you probably have some combination of these skills. The opportunity is real. The projects are tractable. The science is waiting.

Stop building another embedding. Start building a simulator.

References

-

Biological World Models Ideation Report. "The In-Silico Cell: Architecting World Models for Biological Systems." User-provided research material, 2025.

-

Ghosh, D., Walke, H., Pertsch, K., Black, K., et al. "Octo: An Open-Source Generalist Robot Policy." arXiv:2405.12213, 2024.

-

CellFlux Team. "CellFlux: Simulating Cellular Morphology Changes via Flow Matching." arXiv:2502.09775, 2025.

-

Neural ODE Research Group. "Neural Ordinary Differential Equations for Simulating Metabolic Pathway Dynamics in Engineered Organisms." arXiv:2512.08732, 2024.

-

Cui, H., Wang, C., Maan, H., et al. "scGPT: toward building a foundation model for single-cell multi-omics using generative AI." Nature Methods 21: 1470-1480, 2024.

-

Theodoris, C.V., et al. "Geneformer." Hugging Face Model Hub, 2024.

-

Lange, M., et al. "CellRank 2: unified fate mapping in multiview single-cell data." Nature Methods 21: 1040-1050, 2024.

-

Perturbation Benchmark Consortium. "Benchmarking algorithms for generalizable single-cell perturbation response prediction." Nature Methods, 2025.

-

Research Summary. "Research Catalogue: Biological World Models for Computational Biologists." Internal research compilation, 2025.

-

scvi-tools Team. "scvi-tools documentation." Available at: https://docs.scvi-tools.org/

-

Kidger, P., et al. "Equinox: neural networks in JAX via callable PyTrees." arXiv:2111.00254, 2021.

-

Schiebinger, G., et al. "CellOT: Learning single-cell perturbation responses using neural optimal transport." Nature Methods 20: 1196-1205, 2023.